Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 154–179, 2010

0160-7383/$ - see front matter Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Printed in Great Britain

www.elsevier.com/locate/atoures

doi:10.1016/j.annals.2009.08.004

GROUP PACKAGE TOUR

LEADER’S INTRINSIC RISKS

Kuo-Ching Wang

National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan

Po-Chen Jao

Hsi-Chen Chan

Chia-Hsun Chung

Chinese Culture University, Taiwan

Abstract: This paper explores the intrinsic risks and risk perception of Taiwanese tour leaders

in terms of group package tour (GPT). Both qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys are

employed in the study. Based on in-depth interviews with 24 GPT leaders, the study identifies

the comprehensive risk items. Moreover, 12 risk factors are extracted through questionnaire

surveys with 310 GPT leaders. Three clusters regarding to risk sources are also categorized:

exogenous risks, tourist-induced risks, and tour leader’s self-induced risks. Furthermore,

the study compares risk perception of 12 factors by means of six itineraries. Finally, several

academic and managerial implications about the GPT tour risk controls were outlined as well.

Keywords: risk, group package tour (GPT), tour leader. Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights

reserved.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there has been dramatic growth in outbound tours

from Asian countries, fuelled by the region’s rapid economic growth

and rising income levels (China National Tourism Administration,

2007). The international tourism industry is now witnessing an increasing number of inbound tourists from Asia, such as Australia (Reisinger

& Turner, 2002) and Guam (Iverson, 1997). Moreover, as a result of

easing restrictions on outbound tours by China, the number of Chinese tourists is expected to increase rapidly in the future.

Asian and Chinese tourists normally take all-inclusive tour packages

as compared with Western tourists (Wong & Lau, 2001), especially for

international trips (Hooper, 1995). In many Asian countries and areas,

the group package tour (GPT), or in the language of Cohen’s (1972)

organized mass tour, is one of the main modes of outbound tour

(March, 2000; Wang, Hsieh, Yeh, & Tsai, 2004; Yamamoto & Gill,

Kuo-Ching Wang, Professor (Graduate Institute of Hospitality Management and Education,

National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan. Email <gordonwang@ntnu.edu.tw>), his

research interest is tourism marketing. Po-Chen Jao, Doctoral Student, his research interests

include tourism marketing and advertising. Hsi-Chen Chan, Doctoral Student, her research

interests include tourism marketing and group package tour. Chia-Hsun Chung, Graduate

Student, his research interests include tourism marketing and group package tour.

154

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

155

1999). For example, in Taiwan, according to government’s statistical

data, outbound tourists had grown to 95.74 million from 1992 to

2006. For sightseeing purposes, almost half of the tourists participated

in GPTs (Tourism Bureau, 2007). As another example in China, outbound tourists had reached 34.52 million in 2006, indicating an increase of 11.3% from 2005 (31.02 million), and the number of

tourists for outbound GPTs had increased from 6.79 million in 2005

to 8.43 million in 2006, an increase of 21.68% (China National Tourism Administration, 2007).

Previous studies have indicated that service industries are highly

dependent on ‘‘contact employees’’ who have a strong influence on

the service quality as perceived by the consumers (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1985; Vogt & Fesenmaier, 1995). In GPTs, usually, a

travel agency assigns a tour leader to accompany the tour. Therefore,

customer relationship is mediated almost entirely by a tour leader.

Accordingly, the tour leader’s behavior will be the predominant factor

influencing the customer’s perception on travel service quality (Wang,

Hsieh, & Chen, 2002; Wang et al., 2004). Quiroga (1990) clearly

pointed out that the function of the tour leader within the group is

considered to be indispensable by the tourists themselves, and the

quality of the tour leader can be a crucial variable in the tour; his or

her presentation can make or break a tour.

In brief, GPTs are a very popular outbound tour mode in many Asian

countries and the tour leader plays an important role in GPTs (Quiroga,

1990; Wang, Cheng, & Wu, 2002). However, prior risk studies examined

risk primarily from the tourist’s perspective (Pinhey & Iverson, 1994;

Roehl & Fesenmaier, 1992; Sönmez & Graefe, 1998a; Teng, 2005). Nevertheless, who should be responsible for the tourists’ safety is still a controversial issue (Robinson & Marlor, 1995). For GPT tourists, the

tourists’ safety primarily is the tour leader’s responsibility. However,

the important questions, such as ‘‘What risks might have occurred while

the tour leader is leading the GPT ?’’ and ‘‘What’s the relationship between different risks with different GPT itineraries?’’ have not yet been answered. As a

result, tour leaders’ experience upon risks is worthy to be discovered.

In practice, the possible risks that one might face during tours are

the priority needed to be considered while planning GPTs. If risk is

viewed as possible loss (Teng, 2005), it is reasonable to assume that a

tour leader’s risks might generate some service failures and then those

failures might entail certain tourist’s losses and finally decrease the extent of the tourist’s perception of service quality in GPT. Therefore, it

is imperative for travel agency managers and tour leaders to augment

their perception and understanding of intrinsic risks in GPT leaders

in terms of risk control strategies, cost reduction, and service quality

control in GPT (Tesh, 1981; Tsaur, Tzeng, & Wang, 1997).

INTRINSIC RISKS IN GPT LEADERS

Risk has become one of the most hotly debated issues in Western

societies today (Okrent & Pidgeon, 1998), and it has been successfully

156

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

incorporated decision-making theories in economics, finance, and the

decision sciences (Cho & Lee, 2006; Dowling & Staelin, 1994). Unser

(2000) indicated that risk and its measurement are still fascinating topics for studies in decision making under risk. In the marketing discipline, the concepts of risk and perceived risk were first discussed in

Bauer’s (1960) ‘‘Consumer Behaviour as Risk Taking’’ research (Bettman, 1973; Stone & Grønhaug, 1993). Since the introduction of the

concept of perceived risk by Bauer, much research has been carried

out by utilizing the concepts of risk and risk reduction processes in

consumer decision making (Bettman, 1973) and many studies have

measured risk perception in a wide variety of contexts (Mitchell &

Boustani, 1994).

In the tourism field, several studies have discussed risk analysis issues,

for example, Tsaur et al.’s (1997) study on tourist risks in GPT. They

defined the risk from ‘‘process of tour’’ and ‘‘destination’’ perspectives

and classified risk into seven evaluative aspects: transportation, law and

order, hygiene, accommodation, weather, sightseeing spot, and medical support. In addition, many studies adopted five risk dimensions

identified by Jacoby and Kaplan (1972) which were financial risk, performance risk, physical risk, social risk, and psychological risk (Cheron

& Ritchie, 1982; Mitra, Reiss, & Capella, 1999). Some studies adopted

six dimensions (Stone & Grønhaug, 1993; Stone & Mason, 1995), by

including time risk as suggested by Roselius (1971). Moreover, several

studies focused on a particular dimension, such as political instability

(Seddighi, Nuttall, & Theocharous, 2001), terrorism (Sönmez & Graefe, 1998a, 1998b), health concerns (Carter, 1998; Lawton & Page,

1997), crime (Pizam, Tarlow, & Bloom, 1997; Pizam, 1999), and satisfaction which first appeared in the study regarding perceived risk

and leisure activities (Cheron & Ritchie, 1982).

Furthermore, Roehl and Fesenmaier (1992) used seven different

types of risks, namely equipment risk, financial risk, physical risk, psychological risk, satisfaction risk, social risk, and time risk, to measure

the risk perceptions of pleasure tourists’. Pinhey and Iverson (1994)

once explored the safety concerns regarding typical vacation activities

among Japanese tourists to Guam. The authors categorized the evaluative aspects of tour safety concerns into seven items: the perceptions

of the described safety, sight-seeing safety, water sports safety, beach

activity safety, night life safety, in-car safety, and road safety. Although

these existing risk/safety studies provided useful information, they did

not take tour leaders’ risk perception into consideration. Besides, most

previous investigations focused on perceived risk, yet this study

explores tour leaders’ experience with risks that have actually been

realized.

More specifically, according to Wang, Hsieh, and Huan (2000), tours

can be categorized into two major modes: GPTs and independent tours;

this categorization is similar to Cohen’s (1972) typology of international

tourists based on their preference for either familiarity or novelty when

traveling, namely, organized mass tourist and individual mass tourist/

explorer/drifter. The tourists on GPTs are Cohen’s organized mass

tourists who prefer the greatest amount of familiarity and travels in

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

157

an ‘‘environmental bubble’’ of the familiar on a packaged tour. Lepp

and Gibson (2003) verified tourist role based on Cohen’s typology

was the most significant variable in relation to risk perception, with

familiarity seekers being the most risk adverse. They indicated that

the organized mass tourists who seeking familiarity are likely to view

alien environments as more risky than the other tourist roles. Besides,

Lepp and Gibson (2003) specified that different types of tourists perceived risks differently: organized mass tourists perceived terrorism as

a greater risk and concerned more on strange food and health risks

than the other types of tourists. As such, what organized mass tourists

perceived as a risk is different to the other three types. Accordingly,

tourist risk based on Wang et al.’s (2000) tour typology can be categorized into: independent tourists’ risk and group package tourists’ risk.

However, in Sönmez and Graefe (1998a) and Roehl and Fesenmaier’s (1992) studies, they mainly focused on independent tourists’ perceptions of the types of risk present in tours. Meanwhile, in Roehl and

Fesenmaier’s (1992) study, all the trips were either in-state or out-ofstate destinations and most of the respondents traveled with family

members. However, the risk perceptions between the independent

and group package tourists’ are rather different because of the tours’

characteristics. Besides, both Sönmez and Graefe (1998a) and Roehl

and Fesenmaier’s (1992) risk components are too broad to measure;

for example, for measuring physical risk component, the question

was asked as follow: possibility that a trip to this destination will result in

physical danger, injury or sickness. For such question, it seems difficult

to fully conceptualize what physical risk actually entails.

Furthermore, in Tsaur et al.’s (1997) study, only physical and equipment risks in GPTs were emphasized. In fact, several important GPT

sectors which have been indicated in prior studies were overlooked,

such as shopping and optional tour (Wang et al., 2000). These neglected sectors essentially entail certain important risks that a tour leader might encounter during the GPT. Moreover, in Pinhey and

Iverson’s (1994) study on safety concerns, only independent tourists’

risks like how safe is it driving a rental car on Guam were focused on. In

addition, several tour or GPT related risks such as: restaurant, hotel,

coach, shopping, optional tour, etc., were not taken into consideration.

Finally, in a recent tour risk perception study by Teng (2005), seven

risk aspects developed by Tsaur et al. (1997) were employed to evaluate

the destination risks for Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore. Although

the methodology and findings in this study are instructive, several

important GPT sectors were overlooked, such as shopping and optional tour (Wang et al., 2000). Moreover, since Teng’s study was essentially a duplication of Tsaur et al.’s (1997) tour risk study, its

contribution to the existing knowledge is not quite apparent.

Thus, it appears that in the relevant theories, the intrinsic risks perceived by GPT leaders have not been clearly identified. Besides, from a

practical viewpoint, perceptions and understandings of risk are important factors influencing the conceptualization of risk control strategies

(Tesh, 1981). Consequently, in order to complement the previous

studies (e.g., Teng, 2005; Tsaur et al., 1997) which merely discussed

158

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

the risk from the perception of tourists, the present study were primarily to (1) explore the intrinsic GPT leaders’ risks and introduce a

grounded model of it, (2) examine the relationship between different

GPT leaders’ risks with different GPT itineraries, and (3) explore the

risk categorizations of GPT leaders.

Study Methods

Unlike previous studies that mainly utilized quantitative approach

(Roehl & Fesenmaier, 1992; Teng, 2005; Tsaur et al., 1997), this study

employed both qualitative and quantitative methods, which is complementary. Mixing both methods can help avoid the problem of a common method variance in using only one method of measurement

because the strengths of one method can counteract the weaknesses

of another (Jick, 1979). Moreover, this is to enhance confidence in

the research result and provide a more comprehension of domain under investigation. Therefore, this study employed both qualitative and

quantitative methods, from in-depth interviews to questionnaire surveys conducted on tour leaders. The qualitative approach was used

to gain a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the

intrinsic risks in GPT leaders. Subsequently, to further examine the

relationship between different risks with different GPT itineraries

and classify the risk categorizations of tour leaders, the quantitative

method was used. Both qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys

were conducted in the language of Chinese.

Definition of Intrinsic Risk in GPT Leaders. Although risk concept was

varied in keeping with diverse research purposes (Stone & Grønhaug,

1993) and was not easy to operationalize (Klinke & Renn, 2001; Unser,

2000), Klinke and Renn (2001) stated that all risk concepts have one

commonality: risk is often associated with the possibility that an undesirable state of reality may occur as a result of natural events or human

activities. With respect to risk analysis, Steene (1999) once suggested

that risk analysis denotes the systematic examination of a course of

events for the purpose of identifying the incidents and phenomena

that can lead to undesired consequences, as well as the assessment of

these consequences and the judgment of their probability. Thus,

according to Steene, risk analysis has three main aspects: (1) identification of the sources of risks, (2) judgment of probability, and (3) analysis of the consequences. Therefore, based on above information, the

operational definition of intrinsic risks in GPT leaders in this study is:

any events or accidents that would cause possible loss while tour leader is leading

the outbound GPT.

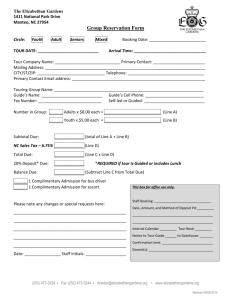

Qualitative Questions Development. The questions were developed into

two parts. In the first part, the travel duration of an outbound GPT is

normally long and covers diverse dimensions, as suggested by Wang

et al. (2000), the GPT was divided into discrete sectors. There are

two advantages to this approach. One is that it can facilitate data

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

159

collection; moreover, the precise definition of GPT sectors is conducive to eliciting the tour leaders’ recollections. The other advantage is

that dividing the GPT into sectors can prevent some sectors from

being overlooked. Accordingly, Wang et al.’s (2000) nine GPT sectors, namely, the pre-tour briefing, airport/plane, hotel, restaurant,

coach, scenic-spot, shopping, optional tour, and others, were employed in this study.

However, in Wang et al.’s study, they did not separate the sector

of airport from airplane; moreover, and they did not take different

departure and arrival airports into consideration. Since different

risks might be encountered at airports (departure and arrival)

and in the airplanes, to prevent the omission of important intrinsic

risks faced by tour leaders in outbound GPTs, the airport/plane

sector was further divided into five sectors: departure airport

(home country), airplane (forth and back), arrival airport (destination country), departure airport (destination country), and arrival

airport (home country). Consequently, a total of 13 sectors were

employed to explore tour leaders’ experiences with risks that have

actually been realized in this study. The detailed questions were

presented in Figure 1; the following is an example of the hotel sector in GPTs:

Q1: According to your personal experiences in leading GPTs, were

there any events or accidents happening that caused you losses while

staying in the hotel ?

In the second part, Rundmo (2002) and Rundmo and Sjöberg

(1998) once indicated that when thinking about a risk source or potential hazard, people may be worried or feel unsafe. Thus, an affective

component is involved in risk perception. For example, the affect of

worry may be evoked every time a person thinks about a risk source.

Since the current study aims at constructing a comprehensive source

structure of intrinsic risks in outbound GPT leaders, therefore, Rundmo and Sjöberg’s ideas of risk and risk perception were taken into

consideration for developing questions in order to capture tour leaders’ perception of possible or future risks. The following question

was framed by taking the hotel sector as an example; the complete questions were also presented in Figure 1.

Q2: With the exception of things mentioned above, what might be the

events and accidents that you would least expect to happen while staying in the hotel ?

Qualitative Data Collection. Since the study was exploratory in nature, it

aimed at eliciting GPT leader’s viewpoints on the intrinsic risks in

tours. To achieve this, in-depth interviews were the most suitable approach. According to Wester-Herber and Warg’s (2002) study, personal experiences, age, gender, and regional differences influence

the individual’s risk perception. However, regional difference was excluded in this study because Taiwan is fairly small in its territory. Therefore, before in-depth interviews, personal experiences, age, and gender

160

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Figure 1. The Hierarchical Structure of Questions

were employed as criteria for selecting the appropriate participants in

order to enhance data quality and increase generalization. In total, 24

tour leaders were conducted; the interviewees’ profile is presented in

Table 1.

To enhance the validity of data analysis, data triangulation technique

was employed for data collection (Jick, 1979). Decrop (1999) indicated

161

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Table 1. Profile of Interviewees (n = 24)

Experience

Gender/Age

Male

With Throughout Guide Experiences*

Sample Size Female

Sample Size

Age 2535

Age 3645

Age 4655

2

2

2

Age 2535

Age 3645

Age 4655

2

2

2

Without Throughout Guide Experiences Age 2535

Age 3645

Age 4655

2

2

2

Age 2535

Age 3645

Age 4655

2

2

2

Total

12

12

*

In Taiwan, China, etc., throughout guide represents that tour leader plays two roles at the

same time while leading the outbound GPTs, one role is the tour leader and the other is the

local guide. Typically, throughout guide would be mostly found in the long-haul outbound

GPTs, such as Europe, New Zealand, Australia, America, etc.

that triangulation means looking at the same phenomenon, or

research question, from more than one source of data and this is useful

for supporting the results. Information coming from different angles

can be used to corroborate, elaborate or illuminate the research problem. It limits personal and methodological biases and enhances a

study’s generalizability. For this purpose, two experts and two scholars

were recruited for data collection. In total, 28 respondents participated

in the in-depth interviews. Each interview lasted approximately 1.5-2

hours. All of the above respondents were interviewed with the questions in Figure 1.

Member Checking. Before the data analysis, a member checking was

conducted to verify the credibility of the interview data (Decrop,

1999). All the 28 transcripts were returned, among them, 14 transcriptions did not require further amendments, the other transcripts

respectively indicated some typing-errors, new events/accidents were

found, and some events/accidents were revised.

Qualitative Data Analysis. The overall process of this part was divided

into three parts: unit of analysis, category development and reliability,

and category confirmation. Part one, as indicated by Holsti (1968) and

Kassarjian (1977), the first step in data analysis is to determine the

appropriate unit of analysis. In this study, the basic units of analysis

were the intrinsic risks in GPT leaders’ risks which resulting from

events or accidents. For instance, in the coach sector, an interviewee

responded that

‘‘. . .when I [female tour leader] was leading a tour to Europe, the

coach driver asked me to sleep with him. I think sexual harassment

is truly one of the risks when female GPT leaders leading a tour. . ..’’

162

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

The above-mentioned example implies that the sexual harassment

from driver toward tour leaders has actually caused psychological

and physical harm to them. Therefore, such an event would be coded

into a risk unit of analysis and called ‘‘sexual harassment from the

driver.’’

Then, two judges (A and B) (both had plenty working experiences in

a travel agency) independently coded the transcriptions from the 26

questions into 1,809 units of analysis (Q1 and Q2). Upon completing

the coding of the unit of analysis, the two judges compared their decisions and resolved disagreements by discussion with the researchers.

Nevertheless, some of the above units were of doubtful relevance to

the study. In the viewpoint, judge A and B and the researchers conducted a screening procedure. In total, 194 units in Q1 were found

to be irrelevant and 398 units in Q2 were found to be identical to the

units in Q1: those units were ultimately eliminated. Finally, 1,217 units

of analysis were obtained for further category development (see Table

2).

Part two, category development and reliability, after the basic unit of

analysis was established, the 1,217 units were divided into categories.

The single classification concept for category development, recommended by Weber (1990), was employed. In an iterative process conducted by judge A and B, each of the units was read out, classified,

re-read, and re-classified. Finally, 135 inferred categories emerged within the 13 GPT sectors (see Table 2), and each of these categories was

named. After the categorization process was complete, this study tested

the reliability of the categorization process.

According to Keaveney (1995), if the inter-judge and intra-judge levels of agreement reach .80, the categorization process can be regarded

as reliable. This study introduced judge C, an Assistant Professor in the

Department of Tourism Management who also had working experience in travel agency, in order to conduct inter-judge reliability testing.

And a time-lag of two weeks was employed for the intra-judge (A and B)

reliability testing, as suggested by Davis and Cosenza (1993). Judge C

categorized all of the 1,217 units into the categories created by judges

A and B and was encouraged to create new categories if appropriate

(Keaveney, 1995; Wang et al., 2000). The result of the inter-judge reliability was .993 for judge C, and no new categories emerged. With respect to the intra-judge reliability which were all above .996 for both

judge A and B.

Part three, category confirmation, in addition to the interviews conducted on the 24 tour leaders, two senior travel experts and two scholars were also interviewed to further category confirmation. In total, 441

units of analysis emerged from two experts and two scholars. Judge A

and B then tried to categorize these 441 units into the 135 categories

with the aim of developing new categories; however, no new categories

emerged in this confirmation process. This result is consistent with Decrop’s (1999) view that triangulation consists of strengthening qualitative findings by showing that several independent sources converge on

them. Therefore, the categories in this study have content validity and

no further interviews were necessary.

Table 2. The Intrinsic Risk Units of Analysis

Outbound

GPT

Sectors

Total

Q2a

Total

Original

Units

Removed

Units

Remained

Units

Obtained

Categories

Original

Units

Removed

Units

Remained

Units

Obtained

Categories

Remained

Units

Obtained

Categories

(%)b

174

100

8

17

166

83

17

13

56

30

51

24

5

6

2

3

171

89

19

16

14.1

11.9

207

130

98

36

9

27

171

121

71

12

11

9

38

35

37

36

35

28

2

0

9

1

0

2

173

121

80

13

11

11

9.6

8.1

8.1

137

10

127

10

32

32

0

0

127

10

7.4

134

41

93

10

38

38

0

0

93

10

7.4

86

75

9

5

77

70

8

9

42

28

41

28

1

0

1

0

78

70

9

9

6.7

6.7

67

2

65

9

20

20

0

0

65

9

6.7

114

49

23

5

91

44

7

6

31

29

31

28

0

1

0

1

91

45

7

7

5.2

5.2

16

2

14

4

6

6

0

0

14

4

3.0

1,387

194

1,193

125

422

398

24

10

1,217

135

100

163

a

Q1: According to your personal experiences in leading GPTs, were there any events or accidents happening that caused you losses while. . .? Q 2: With the

exception of things mentioned above, what might be the events and accidents that you would least expect to happen while. . .?; b % = individual category/

total categories (135 categories).

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Coach

Departure

airport

(destination)

Hotel

Scenic-spot

Airplane

(forth and

back)

Arrival

airport

(destination)

Departure

airport

(home)

Shopping

Optional

tour

Arrival

airport

(home)

Restaurant

Pre-tour

briefing

Others

Q1a

164

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Grounded Model of Intrinsic Risks in GPT Leading. According to Table 2,

which showed the number of categories for each GPT sector, the three

main risk sectors as perceived by tour leaders were ‘‘coach’’, ‘‘departure airport/destination country’’, and ‘‘hotel’’ and the least-mentioned sector was ‘‘others’’. Taking the most noteworthy findings in

‘‘coach’’ as an example, this sector represents 14.1%, the largest sector

of all of risk categories (19/135).

In this sector, ‘‘poor vehicle conditions’’ was major concern of

tour leaders (41/171, 24.0%). The chief source of risk mainly comes

from vehicles being too old and lacking cleaning, microphone malfunctions, or air conditioning not cold enough. Second largest category was ‘‘property loss of the GPT tourists’’ (22/171, 12.9%).

Moreover, six out of the 19 categories of risk were related to coach

driver, among them, risks mainly came from the ‘‘poor attitude of

the driver’’ (20/171, 11.7%) and ‘‘unprofessional driver’’ (13/171,

7.6%). The results revealed in Europe or USA, because of drivers’

multi-national background, language barrier sometimes causing

problems in the interaction and cooperation with the tour leader,

for instance,

‘‘I once led a group to Europe and got an Italian driver. His English

was so poor that we had to communicate with hand signs. This would

affect the whole group’s rhythm and mood.’’

In summary, because the coach is the most relied upon transportation in a GPT tour, the driver is the tour leaders’ working partner with

the most frequent interactions. Therefore, if the driver’s attitude and

professionalism is poor, it will not only affect the flow of the entire trip

but also deal a severe blow to the tour leader’s mood when leading the

group.

Quantitative Questionnaire Development. On the basis of qualitative

results, a questionnaire was developed in three parts. In the first

part, two questions were designed to capture the tour leaders’ professional backgrounds. One question asked the tour leaders to identify his/her most specialized itinerary from six GPT itineraries,

namely, China, Thailand, Japan, USA, New Zealand/Australia, and

Europe; these six GPT itineraries were selected either because they

are the most popular GPT itineraries in practice or they are among

the top five destination countries for outbound GPTs in Taiwan

(Tourism Bureau, 2007). Another question asked each respondent

indicate the frequency of this GPT itinerary that he/she has been

leading. In the second part, 13 GPT sectors with 135 categories

were rewritten to develop an original scale wherein each category

was anchored with a five-point scale ranging from ‘‘extremely

impossible’’ to ‘‘extremely possible’’. The following is an example of a

question pertaining to ‘‘unprofessional driver’’ category in the ‘‘coach’’

sector:

Q: According to your personal experiences in leading your most specialized GPT, in the coach sector, the possibility of confronting an

unprofessional driver is?

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

165

Except those 135 questions, two questions were designed as reversed

statement in order to eliminate potential biased. Moreover, an openended question like ‘‘Except for the above-mentioned risk features, if there

are any risk features that you think important, please specify and write them

down below’’ is also included in each sector to detect whether or not

the risk categories obtained from the qualitative analysis is comprehensive. In the third part, several questions were included to capture the

tour leaders’ demographic profiles, such as gender, age, education,

average monthly income, how many years for being GPT leader, and

the name of the travel agency that the tour leader works for.

Prior to the data collection, two doctoral and two EMBA students

who presently work for a travel agency were invited to assess the content and relevance of this questionnaire. In addition, 30 undergraduate students from the Department of Tourism Management were

also invited to evaluate the comprehension of the words and phrases

of items. Based on their comments, some revisions were made to improve the clarity of the items.

Quantitative Data Collection. The survey was conducted by different travel agency managers who volunteered to collect the questionnaires in

Taiwan. The data collection was carried out over a three-month period.

In total, 650 questionnaires were distributed, 437 surveys were returned, and of those, 310 were useable for the purpose of analysis.

From the years for being outbound tour leader and frequency of leading the most specialized itinerary, the statistics of cross tabulation reveals that 64.4% of the respondents have at least five years and above

experience as tour leaders and all of them have led a specialized

GPT itinerary at least six to ten times and above. Besides Europe was

identified as the most specialized GPT itinerary (21.6%), followed by

Thailand (19%), and China (18.1%). A total of 75 major travel agencies were surveyed. Among them, 19 were wholesale travel agencies,

which constitute 23% of the total wholesale travel agencies (81) in Taiwan (Tourism Bureau, 2007).

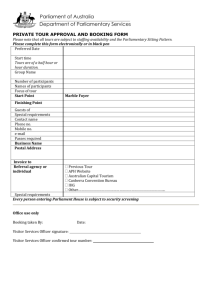

The Risk Measurement of Six GPT Itineraries and 13 Sectors. According to

Table 3, China was viewed as the most risky destination, followed by

Thailand, USA, Europe, New Zealand/Australia, and Japan. Analysis

of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to test whether there were significant differences in the risk measurement of these six itineraries. The

result reveals significant differences in these six itineraries. On the basis of the homogeneous subsets test (Scheffe, alpha at .05 level), they can

then be categorized into four different groups as follows: China and

Thailand (a), USA and Europe (ab), New Zealand/Australia (bc),

and Japan (c). With respect to the risk in different GPT sectors,

‘‘pre-tour briefing’’ was ranked as the most risky sector and ‘‘departure

airport (destination)’’ as the least risky sectors. Except ‘‘others’’ sector,

12 of the 13 GPT sectors were found to have significant differences. For

the homogeneous subsets test, most sectors were categorized into three

or four different groups. Interestingly, for three sectors (airplane/

forth and back, arrival airport/home, and others) the heterogeneous

China/

561

Thailand/

59

Japan/

51

USA/

43

New Zealand/

Australia/34

Europe/

67

Average

score

Ranking

F

p

1

13 GPT Sectors with 135 Categories

Pre-tour

briefing

Departure

airport

(home)

Airplane

(forth/

back)

Arrival

airport

(destination)

Coach

Scenicspot

Restaurant

Optional

tour

Hotel

Shopping

Departure

airport

(destination)

Arrival

airport

(home)

Others

Average

score

Ranking

3.37a*

2.86a

2.66a

2.68a

2.68a

2.82a

2.66a

2.66a

2.65a

2.76a

2.54a

2.50a

2.62a

2.71a (.34)2

1

2.49

a

2.75

a

2.60

a

a

2.76

a

2.10

b

1.99

c

2.12

c

2.51

a

2.52

a

2.59

a

2.46

ab

2.76

a

2.11

b

2.21

bc

2.19

bc

2.54

a

2.49

a

2.51

ab

2.43

abc

2.38

2.55

a

2.35

(.50)

12

3.24

.007

2.62

(.63)

3

1.55

.172

2.71

ab

2.38

b

2.69

ab

2.45

b

3.22

2.63

ab

3.21

(.67)2

1

4.42

.001

2.63

(.60)

2

4.43

.001

3.23

ab

b

2.84

a

3.38

3.20

ab

ab

2.69

a

2.49

a

2.64

a

2.44

a

2.50

a

2.58

(.49)

4

2.28

.046

2.53

ab

2.10

c

2.60

a

2.24

bc

2.54

ab

2.47

(.54)

8

9.90

.000

2.59

a

2.14

c

2.51

ab

2.24

bc

2.57

a

2.48

(.52)

6

9.39

.000

2.61

ab

2.30

bc

2.61

ab

2.27

c

2.67

a

2.57

(.53)

5

8.91

.000

2.42

(.56)

10

8.96

.000

2.48

(.61)

7

13.62

.000

2.43

(.51)

9

9.68

.000

2.49

ab

1.95

c

2.33

b

2.24

bc

2.28

bc

2.35

(.55)

11

15.47

.000

2.31

ab

2.01

c

2.37

a

2.05

bc

2.34

ab

2.29

(.46)

13

10.98

.000

2.38

a

2.16

a

2.40

a

2.19

a

a

2

c

2.20 (.36)

6

2.57

ab

(.38)

3

2.29

bc

(.51)

5

2.53

ab

(.46)

4

2.59 (.35)

2.50

(.43)

11.19

.000

Number represents how many GPT leaders have identified this itinerary as his/her most specialized route; 2 Number in the parenthesis represents the

standard deviation; * Means with two (ab) or three (abc) superscripts represent at two or three different homogeneous subsets based on Scheffe tests, alpha at

.05 level.

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Most

Specialized

GPT

Itineraries

166

Table 3. Risk Measurement of Six GPT Itineraries

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

167

subsets were not identified which represent these three sectors have

similar level of risks on these six outbound itineraries.

Purify the Intrinsic Risks in GPT Leaders

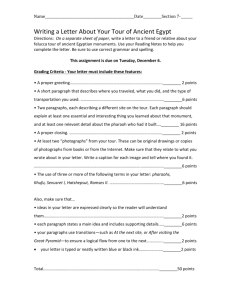

Exploratory Factor Analysis. According to the suggestions by Churchill

(1979) and Wang, Hsieh, Chou, and Lin (2007), an exploratory factor

analysis (EFA) was employed to develop a reduced and more parsimonious measurement of intrinsic risks in GPTs. This study used the raw

scores of the original scale to conduct the EFA. The items of EFA have

been eliminated from 135 to 38 items. As a result, the communality of

each item exceeded .66 and all factor loadings were exceeded the required value of .4 (del Bosque, 2008; Stergiou, Airey, & Riley, 2008).

The 38 items for the GPT leaders’ perceived risk produced 12 factors

with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0. The reliability of each factor exceeded .76. These factors explained 73.95% of the variance. The detailed factors and items presented in Table 4.

Cluster Analysis. This study employed 12 groups of factor scores derived from the EFA in the cluster analysis. The K-means clustering

method, a nonhierarchical algorithm (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, &

Black, 1991), was used to determine the optimal number of clusters

on the basis of these factors. As a result, the three-cluster solution

was the most appropriate for the data of tour leaders’ perceived risks.

Moreover, each cluster’s name was denominated in accordance with

the manifestation of factor means. The multivariate statistics showed

significant differences between the three clusters (p < .001).

The results indicated that cluster one has significantly higher mean

of factors (M = 3.4, mean of cluster one = 3.02) in ‘‘hijacking and plane

crash’’, ‘‘optional tour and shopping’’, ‘‘document and property stolen’’, ‘‘luggage lost’’, ‘‘driver problems’’, and ‘‘bribery and obstruction

by customs officers’’ than the other clusters. These factors are related

to the externals; therefore, this cluster was named as ‘‘exogenous risk’’

cluster. Most of exogenous risks cannot be controlled during the tour.

Cluster two had comparatively higher mean of factors (M = 3.01, mean

of cluster 2 = 2.69) in ‘‘sexual harassments and accusation from tourists’’, ‘‘tourist’s compensation problems associated with damages and

hotel expense’’, ‘‘tourist’s taxable and prohibited goods’’, and ‘‘tourist’s visa and passport expiration issues’’. These factors are related to

the tourists; as a result, cluster two was named as ‘‘tourist-induced risk’’

cluster. Cluster three had comparatively higher mean of factor

(M = 2.5, mean of cluster three = 2.2) in ‘‘change in itinerary and tipping problems’’ and ‘‘tour leader’s operating negligence’’, followed

by the exogenous risk. These factors are related to the tour leaders;

accordingly, cluster three was named as ‘‘tour leader’s self-induced risk’’

cluster. Moreover, the results showed that exogenous risks cluster have

the highest explanation power (37%), followed by tourist-induced risks

cluster (24%) and tour leader’s self-induced risks cluster (13%) (see

Table 5).

168

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Table 4. Results of Factor Analysis of the Perceived Risk by Tour Leader

Perceived risk factors and items

Optional tour and shopping

overly priced products in sopping store

forced optional tours by local tour guide

fake products and flawed

merchandise in shopping store

forced shopping

GPT tourists complain

over optional tour unworthiness

optional tour not well arranged

Tour leader’s operating negligence

temporary closure of the scenic-spot

schedule delay leading to

the missing a visiting scenic-spot

sudden change of the schedule leading

to missing the visiting scenic-spot

temporary closure of the restaurant

special meals not ordered

Driver problems

poor attitude of the driver

unprofessionalism of the driver

poor physical strength of the driver

Sexual harassment and accusation from tourists

actual product different from the

anticipation of the GPT tourists sales

tour leader wrongfully accused

by the GPT tourists

sexual harassment by the tourists

tourists with deficient traveling knowledge

Bribery and obstruction by customs officers

customs officers asking for bribes in

arrival airport/destination country

customs officers asking for bribes in

departure airport/destination country

hard time getting through customs

Tourist’s compensation problems associated

with damages and hotel expenses

problem of compensation to the

damaged facilities of hotel room

problem over compensation to

loss of objects in hotel room

dispute over payment items

Tourist’s taxable and prohibited goods

taxable goods overweight in arrival

airport/home country

taxable goods overweigh in departure

airport/destination country

GPT tourists carrying prohibited goods

Factor Variance Cronbach Communality

loading explained alpha

(%)

8.833

.788

.666

7.616

.822

.643

6.956

.857

.787

6.304

.763

.666

6.294

.861

.777

6.239

.855

.770

5.784

.814

.718

.771

.709

.701

.696

.548

.422

.787

.728

.674

.581

.479

.812

.807

.768

.748

.708

.699

.603

.841

.781

.766

.845

.796

.687

.807

.714

.616

169

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Table 4 (continued)

Perceived risk factors and items

Change in itinerary and tipping problems

not paying tips

GPT tourists are not given full and

comprehensive information

during the pre-tour briefing

tourist bargain for tip issue

Tourist’s visa and passport expiration issues

passport expires

visa expires

Hijacking and plane crash

hijack

plane crash

Luggage lost and damaged

luggage damaged

luggage loss

Document and property stolen

documents stolen

property stolen

Total variance explained

Factor Variance Cronbach Communality

loading explained alpha

(%)

5.460

.781

.713

5.265

.906

.878

5.217

.951

.880

5.105

.863

.803

4.881

.886

.854

.779

.774

.684

.864

.862

.938

.927

.828

.812

.838

.806

73.95

Note: Each statement was measured on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = extremely impossible to 5 = extremely possible.

Perceived Risks Analysis

Analysis of Six GPT Itineraries and 13 Sectors. After the EFA, the new

ranking of the average scores of the tour leaders’ perceived risks in

six GPT itineraries was found to be similar with the original ranking

(see Table 6). The new risk-ranking of six GPT itineraries from higher

to lower is China, Thailand, USA, Europe, New Zealand/Australia, and

Japan. Moreover, in regarding to tour leaders’ perceived risks in 13 sectors, the results revealed the new ranking of average scores in every factor dimension was apparently different before and after the items were

eliminated. However, in spite of five dimensions, which are airplane,

arrival home airport, arrival destination airport, departure home airport, and shopping; the others deviated all within three positions. Such

an outcome not only indicated the reliability of the new GPT risk model but also provided a more parsimonious measurement which the

items were condensed from 135 to 38 items.

Post-Hoc Test of the Perceived Risk. Post-Hoc analysis was used to report

the differences in 12 factors among six itineraries. Meanwhile, the six

GPT itineraries were adopted as the independent variables of the analysis, and they corresponded with the dependent variables, that is, the

12 perceived risk factors. In Table 7, the numbers in the parenthesis

represent the mean difference between two itineraries; for example,

M-J stands for the mean difference of China minus Japan in relation

170

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Table 5. Results of Cluster Analysis of Perceived Risk

Factors

Cluster 1

Cluster 2

Cluster 3

F value

Exogenous Tourist-induced Tour leader’s

risk

risk

self-induced

risk

1 Optional tour and shopping

3 Driver problems

5 Bribery and obstruction

by customs officers

10 Hijacking and plane crash

11 Luggage lost and damaged

12 Document and

property stolen

4 Sexual harassment and

accusation from tourists

6 Tourist’s compensation

problems

associated with damages

and hotel expense

7 Tourist’s taxable and

prohibited goods

9 Tourist’s visa and

passport expiration issues

2 Tour leader’s

operating negligence

8 Change in itinerary and

tipping problems

3.42

3.33

3.19

2.65

2.62

2.70

2.38

2.27

2.13

96.08*

84.47*

82.06*

3.70

3.38

3.40

2.74

2.11

2.50

2.42

1.76

2.34

42.85*

47.71*

87.64*

2.88

2.79

2.09

67.68*

3.16

3.07

2.39

66.72*

2.75

2.91

1.89

46.23*

1.60

3.28

1.56

50.51*

3.15

2.49

2.44

57.78*

2.38

2.43

2.58

79.97*

n = 68

n = 146

n = 127

lambda = .23

(p < .001)

37%

24%

13%

Explained variance

*

p values are significant at the .001 level.

to 12 factors. The results revealed that among these 12 factors, except

for ‘‘Sexual harassment and accusation from tourists’’, ‘‘Tourist’s taxable and

prohibited goods’’, ‘‘Tourist’s visa and passport expiration issues’’, and

‘‘Hijacking and plane crash’’, eight factors were found to have significant

differences with regard to the GPT itineraries. The mean differences

and explanation of three interesting risk factors in GPT leaders’ on

every GPT itinerary are described in following:

Optional tour and shopping. With regard to this risk factor, apparently,

tour leaders perceived higher risks in China than Japan (.87, p < .001),

New Zealand/Australia (.59, p < .01), and Europe (.54, p < .01); and

also this risk factor is higher in Thailand than Japan (.84, p < .001),

New Zealand/Australia (.55, p < .01), and Europe (.51, p < .01). As indicated by Wang et al. (2000, p. 185), optional tour and shopping are two

of the most important service features in GPTs. The risks are mainly

Table 6. Risk Measurement of Six GPT Itineraries

38 Items for New 13 GPT Sectors

Pre-tour Departure Airplane Arrival

Coach Scenic- Restaurant Optional Hotel Shopping Departure

Arrival Others Average

briefing airport

(forth/ airport

spot

tour

airport

airport

score

(home)

back)

(destination)

(destination) (home)

Ranking3 New

Ranking4

China/591

Thailand/65

Japan/56

USA/50

New Zealand/

Australia/

37

Europe/74

3.02a*

2.88ab

2.47b

3.12a

2.92ab

2.78a

2.56a

2.31a

2.62a

2.40a

1.73a

1.97a

1.93a

1.98a

1.71a

2.42a

2.45a

1.72bc

2.02ab

1.57c

2.57a

2.40a

2.12c

2.48ab

2.01bc

2.89a

2.59ab

2.53bc

2.60ab

2.38c

2.48a

2.29ab

2.21ab

2.36a

2.02bc

2.90a

3.05a

1.99c

2.77a

2.32bc

2.97a

2.76a

2.25bc

2.43ab

2.28bc

2.95ab

2.58a

1.66a

1.91b

2.89a

2.67a

2.44a

2.57ab

Average score

2.89

(.98)2

1

1

4.60

.000

2.54

(.81)

2

7

2.54

.028

1.83

(.83)

4

13

1.95

.085

2.01

(.79)

8

12

17.25

.000

2.41

(.82)

6

9

12.71

.000

2.61

(.72)

5

3

3.91

.002

2.30

(.79)

10

10

3.07

.010

2.60

(.90)

7

4

17.82

.000

Ranking

New Ranking

F

p

1

3.08a

2.86ab

2.06c

2.54bc

2.48bc

2.26a

2.30a

1.94abc

2.14ab

1.87bc

2.77a

2.61a

2.31a

2.70a

2.44a

2.62a

2.75a

2.49a

2.72a

2.58a

2.65a (.34)2

2.57a (.35)

2.17c (.36)

2.49ab (.38)

2.54bc (.51)

1

2

6

3

5

1

3

6

2

4

2.42ab 2.33bc

2.04ab

2.70a

2.52a

2.78ab (.46) 4

5

2.51

(.82)

9

8

10.04

.000

2.09

(.72)

13

11

5.36

.000

2.58

(.77)

12

5

4.59

.000

2.61

(.81)

3

2

1.59

.161

2.77

(.76)

2.55

(.91)

11

6

16.51

.000

7.89

.000

Number represents how many GPT leaders have identified this itinerary as his/her most specialized route; 2 Number in the parenthesis represents the

standard deviation; 3 Number represents the order of tour leader’s perceived risk in the original 135 items; 4 Number represents the order of tour leader’s

perceived risk in the 38 items; * Means with two (ab) or three (abc) superscripts represent at two or three different homogeneous subsets based on Scheffe

tests, alpha at .05 level.

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Most

Specialized

GPT

Itineraries

171

172

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Table 7. Result of Post-Hoc Test of the Perceived Risk by Tour Leader

Factor

Scheffe multiple range tests

M-J

1

(.87)

***

2

3

M-A

M-N

M-E

T-J

(.59) (.54) (.84)

**

**

***

T-A

T-N

T-E

(.55) (.51)

**

**

J-A

J-E

A-E

N-E

(-.54)

**

(.49)

***

(.46)

*

(.56)

**

(-.49)

**

(-.77) (-.42) (-.88)

***

*

***

4

5

(.63) (.39) (.77) (.42) (.69) (.44) (.82) (.47)

***

*

***

**

***

**

***

**

6

(.72) (.55) (.69) (.56) (.51)

***

**

***

**

**

(.48)

*

7

8

(.57)

**

(-.68) (-.47)

***

*

11

(.61)

***

(-.53) (-.62)

**

*

12

(.55)

*

9

10

*p

values are significant at the .05 level;**p values are significant at the .01 level;***p values are

significant at the .001 level.Number in the parenthesis represents the mean difference.Itinerary:

M = China, T = Thailand, J = Japan, A = USA, N = New Zealand and Australia, E = European.

Factor: 1: Optional tour and shopping; 2: Tour leader’s operating negligence; 3: Driver problems; 5: Bribery and obstruction by customs officers; 6: Tourist’s compensation problems

associated with damages and hotel expense; 8: Change in itinerary and tipping problems; 11:

Luggage lost and damaged; 12: Documents and property stolen. Blank column indicates ‘not

significant’.

caused by local agents and local guides in destination. In practice, perceived risks such as forced shopping, deliberate stalling of tourists in

the stores for shopping; incorporate additional shopping spots/optional tour during the main tour are often observed in China and

Thailand.

Driver problems. In this factor, risks perceived in Europe is apparently

higher than other itineraries such as Thailand (.49, p < .01), Japan (.77,

p < .001), USA (.42, p < .05), New Zealand/Australia (.88, p < .001).

Europeans have a strong geographic conception and less desire to

communicate in English. Accordingly, it sometimes creates the

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

173

misunderstandings and communication gaps between European drivers and tour leaders in the itinerary, thus impeding the tour’s progress.

Bribery and obstruction by customs officers. With regard to this factor, China, as expected, ranks higher than Japan (.63, p < .001), USA (.39,

p < .05), New Zealand/Australia (.77, p < .001), and Europe (.42,

p < .01). Thailand also evidently ranks higher than Japan (.69,

p < .001), USA (.44, p < .01), New Zealand/Australia (.82, p < .001),

and Europe (.47, p < .01). Although, nowadays this type of risk is seldom found in many destination countries/airports, while leading the

tour, especially during the CIQ (custom, immigration, and quarantine)

procedures, risks such as ‘‘bribery and obstruction by customs officers’’ are

still perceived by tour leaders in certain destination countries/airports.

CONCLUSION

This study outlines both qualitative and quantitative approaches to

explore GPT leaders’ perception of intrinsic risks. The results obtained

not only fill up the theoretical gap in studies on tour risks but also offer

insights into risk management strategies. The discussions are described

in detail below.

First, with respect to the risk/safety analysis regarding destinations,

most of the prior studies involved the participation of undergraduate

students (Hsu & Lin, 2005) and tourists (Lepp & Gibson, 2003; Pinhey

& Iverson, 1994; Roehl & Fesenmaier, 1992; Sönmez & Graefe, 1998a;

Teng, 2005; Tsaur et al., 1997), most of whom were first-time tourists

(Hsu & Lin, 2005; Roehl & Fesenmaier, 1992). Unlike previous studies,

this study involved the participation of 310 tour leaders from 75 major

travel agencies in Taiwan. Because of their considerable experience in

leading outbound tours, the authors believe that the results can offer a

better understanding/generalization of GPT related risks for the destination risk analysis.

Second, although prior risk/safety studies have briefly discussed risk

factors, they are less specific when addressing the tour leaders’ perceived risks. For example, Roehl and Fesenmaier (1992) identified seven types of travel risks as perceived by independent tourists. However,

these types are too general to allow for a more specific understanding

of the cause of every tour risk. This study excluded tour leaders’ work

characteristics to nullify the results of the previous GPT studies, which

merely consider the risk perception in GPTs from the perspectives of

tourists and destinations. In addition, following Roehl and Fesenmaier’s classification of risk perception by independent tourists, which

was carried out on the basis of the mean scores of a three-factor loading, this study considered the interaction between GPT participants

and the environment to identify three risk clusters, namely, tour leaders’ self-induced risks, tourist-induced risks, and exogenous risks, after

conducting a cluster analysis. This would more accurately prove that

the risk perception of tour leaders is generalized on the basis of the

interaction between tour leaders, tourists, and the environment.

174

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Moreover, although Tsaur et al. (1997) and Teng (2005) utilized the

seven risk aspects, they are inadequate to cover all aspects of GPT risks.

This study takes into consideration the ‘‘process of tour’’ which is divided into before, within, and after the tour, for an analysis of risk perception. Interestingly, some substantial and concrete phenomena were

discovered: before the tour, fewer participants and insufficient information

in pre-tour briefing, and tourist’s visa and passport expiration issues;

within the tour, arguments to incorporate optional tours and shopping

in the main tour, document and property stolen, problem of goods that

are taxable and prohibited for tourists, bribery and obstruction by customs officers, luggage lost and damaged; after the tour, sexual harassment

and accusations from tourists and so on. Thus, this study explores a

more comprehensive intrinsic risks faced by GPT leaders and expands

the foundation of tour-related risk perceptions.

Finally, unlike previous researches on Asian destinations, whose investigations have been limited to the geographic aspects (Teng, 2005; Tsaur

et al., 1997), this study expands its investigation to include China, Thailand, Japan, USA, New Zealand, Australia, and Europe; the territory is

vast, encompassing Asia, America, Oceania, and Europe. Besides, this

study compares risk perception of 12 factors by means of six itineraries.

The results indicated that tour leaders who work on Japan routes perceived less risk with regard to all risk factors than on any other routes.

On the contrary, the China route performs worse in many aspects, followed by the USA and Thailand. On the China route, tour leaders perceived higher risk in the cluster of exogenous risk. This result suggests

that the overall quality of China’s tour sector is waiting to be raised.

Besides, in terms of risk perception with regard to drivers, Europe

ranks higher than Thailand, Japan, and the USA. The bad attitude,

unprofessional conduct, and physical condition of European bus drivers usually lead tour leaders to form negative opinions of the tour.

According to the statistical report of the Ministry of Transportation

and Communications (2007), accidents caused by long-haul shuttle

buses are increasing annually. Many studies have showed that accidents

in the USA (Demos, 1992; Mackie & Miller, 1978) and Europe (Hamelin, 1987) have a fairly significant association with fatigue due to driving for a considerably long period of time. Moreover, according to

the interviews with tour leaders, Europeans have a strong geographic

conception and less desire to communicate in English, thereby leading

to misunderstandings and communication gaps between European

drivers and tour leaders in the itineraries and impeding the tours’ progress. In sum, owing to the inclusion of additional regions in this study,

its results are more generalized than those of the previous studies on

the perception of GPT risks.

Implications

Touring Standard Operating Procedure. By explaining these tour risks

with six itineraries, this study contributes to provide comprehensive

tour risks as well as concrete incidents to help tour leaders understand

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

175

the possible difficulties in different areas. In addition, this study constructs an evaluative chart for tour leaders’ risk factors on the basis

of the theoretical implication of this study. After eliminating the original questionnaire items, the travel agency can develop a clear standard

operating procedure for tour leaders and facilitate the control of GPT

risks. Practically, during tour, a travel agent prepares a detailed itinerary for tour leaders, which usually includes flight numbers, detailed

schedules, name and number of restaurants, souvenir shops, coach

company, and local agency. In addition, the travel agent can design

a complete and exhaustive standard operating procedure to be implemented during tours for managing risks in tour leaders.

Risk Categorizations of GPT Leaders. The results in the cluster analysis

showed that most of the loss in tour leaders’ touring process is due

to exogenous risk. Since most of exogenous risks are uncontrollable, the

coping strategy for such risks is ‘‘precaution’’. Precaution can be effectively exercised by constantly reminding the tour leaders of such exogenous risks during or providing printed material to remind both the

tour leaders and tourists of the same. Besides, a travel agent also can

enhance tour leaders’ risk-management ability by ensuring periodical

training of phenomenon simulation in order to improve tour leaders’

risk perception and reduce loss under uncertainty.

The second type of risk perception in GPT leaders is tourist-induced

risk; tour leaders can control a certain extent of risks in this type. For

instance, tour leaders can provide complete information about the taxable and prohibited goods, expenditures in hotel, etc. in the pre-tour

briefing to avoid certain problems. Moreover, the legal rights and duties between travel agents/tour leaders and tourists should be clearly

stated in the pre-tour briefing to prevent sexual harassment and accusations from tourists. As most of risks in this cluster can be controlled,

the coping strategy for risk type is ‘‘education and rewards’’. This strategy

can be effectively implemented in two ways: first, by continually educating the tour leader of such tourist-induced risks during the tour, and

second, by encouraging the group through rewards to overcome certain likely risks in sectors (e.g., taxable and prohibited goods).

Finally, tour leader’s self-induced risks, which results from the tour leaders’ negligence when they fail to get completely acquainted with information before or during the tour, are extremely lower than the other

types of risk. Meanwhile, the risk of ‘‘change in itinerary and tipping

problems’’ and ‘‘tour leader’s operating negligence’’ can be controlled by following the touring standard operating procedure for risk

management. Since most of the tour leader’s self-induced risks can be

controlled during the tour, the coping strategy for these risks is ‘‘training and penalty’’. This strategy can be effectively implemented, first, by

familiarizing tour leaders those self-induced risks through training as

well as through a printed standard operating procedure, and second,

be clearly stipulating the penalty, in print, for the ineffective management of controllable risks, along with the above-mentioned standard

operating procedure.

176

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Pre-Tour Briefing. The risks stemming from tourist-induced risks and

tour leader’s self-induced risks can be prevented by tour leaders if they

clearly elicit thorough information in the pre-tour briefing. However,

in practice, tourists and travel agents pay little attention to pre-tour

briefing; moreover, the timings of pre-tour briefing are inflexible

and inconvenient, as result of which the tourists’ have less desire to participate in them. Furthermore, the pre-tour briefing is usually held not

by the tour leader but by some inexperienced operators and sales representatives. Under such circumstances, the lack of practical experience and professional knowledge generally leads to a lag in the

communication of tour information. If the standard operating procedure of pre-tour briefing and lag of information is left unchecked, it

will lead to a gap between the service delivery and external communication; this is referred to as ‘‘gap four’’ by Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and

Berry (1988). Certainly, this will manifest into a more severe risk in

GPT leaders’ and the travel agents should undeniably focus on such

serious practical managerial problems.

Finally, the intrinsic risks in the GPT faced by the Taiwanese GPT

leaders are unlikely to be unique. The authors believe that the intrinsic risks found in this study are common to leading professions worldwide. Certainly, it is worthwhile for destination countries to pay closer

attention to this situation, and the findings and ideas put forth

by this comprehensive study could be generalized to the tourism

industry.

Acknowledgements—One year ago, after a car accident, our good friend Chung, Chia-Hsun (the

fourth author of this paper) passed away. All the teammates are truly saddened by the loss of

our good friend. Chia-Hsun’s smile will be embedded in everyone’s mind and heart, and we

do believe now Chia-Hsun is living well in heaven and he will guard us all.

REFERENCES

Bauer, R. A. (1960). Consumer behavior as risk taking. In R. S. Hancock (Ed.),

Dynamic marketing for a changing world (pp. 389–398). Chicago, Illinois:

American Marketing Association.

Bettman, J. R. (1973). Perceived risk and its components: A model and empirical

test. Journal of Marketing Research, 10(2), 184–190.

Carter, S. (1998). Tourists and traveler’s social construction of Africa and Asia as

risky locations. Tourism Management, 19(4), 349–358.

Cheron, E. J., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (1982). Leisure activities and perceived risk. Journal

of Leisure Research, 14(2), 139–154.

China National Tourism Administration (2007). The year book in China tourism in

2006. Beijing, China: China National Tourism Administration.

Cho, J., & Lee, J. (2006). An integrated model of risk and risk-reducing strategies.

Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 112–120.

Churchill, G. A. Jr., (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of

marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73.

Cohen, E. (1972). Towards a sociology of international tourism. Sociological

Research, 39(1), 164–182.

Davis, D., & Cosenza, R. M. (1993). Business research for decision making. California:

Wadsworth Publishing.

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

177

Decrop, A. (1999). Triangulation in qualitative tourism research. Tourism Management, 20(1), 157–161.

del Bosque, I. R. (2008). Tourist satisfaction: A cognitive-affective model. Annals of

Tourism Research, 35(2), 551–573.

Demos, E. (1992). Concern for safety: A potential problem in the tourist industry.

Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 1(1), 81–88.

Dowling, G. R., & Staelin, R. (1994). A model of perceived risk and intended riskhandling activity. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 119–134.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1991). Multivariate data

analysis with readings (3rd ed.). New York: Macmillan.

Hamelin, P. (1987). Lorry driver’s time habits in work and their involvement in

traffic accidents. Ergonomics, 30(9), 1323–1333.

Holsti, O. R. (1968). Content analysis. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The

handbook of social psychology: Research methods (2nd ed., pp. 596–692). Reading

MA: Addison-Wesley.

Hooper, P. (1995). Evaluation strategies for packaging travel. Journal of Travel &

Tourism Marketing, 4(2), 65–82.

Hsu, T.-O., & Lin, L.-Z. (2005). Using fuzzy set theoretic techniques to analyze

travel risk: An empirical study. Tourism Management, 27(5), 968–981.

Iverson, T. J. (1997). Decision time: A comparison of Korean and Japanese

travelers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 16(2), 209–219.

Jacoby, J., & Kaplan, L. B. (1972). The components of perceived risk. In M.

Venkatesan (Ed.), Proceedings of third annual conference (pp. 382–393). Chicago:

Association for Consumer Research.

Jick, T. D. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in

action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 602–611.

Kassarjian, H. H. (1977). Content analysis in consumer research. Journal of

Consumer Research, 4(1), 8–18.

Keaveney, S. M. (1995). Customer switching behavior in service industries: An

exploratory study. Journal of Marketing, 59(2), 71–82.

Klinke, A., & Renn, O. (2001). Precautionary principle and discursive strategies:

Classifying and managing risks. Journal of Risk Research, 4(2), 159–173.

Lawton, G., & Page, S. (1997). Evaluating travel agents’ provision of health advice

to travelers. Tourism Management, 18(2), 89–104.

Lepp, A., & Gibson, H. (2003). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international

tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 606–624.

Mackie, R. R., & Miller, R. R. (1978). Effects of hours of service, regularity of schedules

and cargo loading on truck and bus drivers. Technical Report 1796-F. Coleta,

California: Human Factors Research, Inc.

March, R. (2000). The Japanese travel life cycle. Journal of Travel & Tourism

Marketing, 9(1&2), 185–200.

Ministry of Transportation and Communications (2007). Statistical abstract of

transportation and communications. Retrieved January 12, 2008, from Ministry of

Transportation and Communication. Department of Statistics Web site:

<http://www.motc.gov.tw/mocwebGIP/wSite/np?ctNode=199&mp=2>.

Mitchell, V.-W., & Boustani, P. (1994). A preliminary investigation into pre- and

post-purchase risk perception and reduction. European Journal of Marketing,

28(1), 56–71.

Mitra, K., Reiss, M. C., & Capella, L. M. (1999). An examination of perceived risk,

information search and behavioral intentions in search, experience and

credence services. Journal of Services Marketing, 13(3), 208.

Okrent, D., & Pidgeon, N. (1998). Risk perception versus risk analysis. Reliability

Engineering and System Safety, 59(1), 1–4.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of

service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing,

49(4), 41–50.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multipleitem scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of

Retailing, 64(1), 12–40.

Pinhey, T. K., & Iverson, T. J. (1994). Safety concerns of Japanese visitors to Guam.

Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 3(2), 87–94.

178

K.-C. Wang et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 37 (2010) 154–179

Pizam, A. (1999). A comprehensive approach to classifying acts of crime and

violence at tourism destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 38(1), 5–12.

Pizam, A., Tarlow, P., & Bloom, J. (1997). Making tourists feel safe: Whose

responsibility is it? Journal of Travel Research, 3(3), 23–28.

Quiroga, I. (1990). Characteristics of package tours in Europe. Annals of Tourism

Research, 17(2), 185–207.

Reisinger, Y., & Turner, L. W. (2002). Cultural differences between Asian tourist

markets and Australian hosts, Part 1. Journal of Travel Research, 40(3), 295–319.

Robinson, M., & Marlor, R. (1995). Tourism and violence: Communicating the

risk. In N. Evans & M. Robinson (Eds.), Issues in travel and tourism

(pp. 115–138). Sunderland: Business Educations.

Roehl, W. S., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (1992). Risk perceptions and pleasure travel: An

exploratory analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 30(4), 17–26.

Roselius, T. (1971). Consumer rankings of risk reduction methods. Journal of

Marketing, 35(1), 56–61.

Rundmo, T. (2002). Associations between affect and risk perception. Journal of Risk

Research, 5(2), 119–135.

Rundmo, T., & Sjöberg, L. (1998). Risk perception by offshore oil personnel

during bad weather conditions. Risk Analysis, 18(1), 111–118.

Seddighi, H. R., Nuttall, M. W., & Theocharous, A. L. (2001). Does cultural

background of tourists influence the destination choice? An empirical study

with special reference to political instability. Tourism Management, 22(2),

181–191.

Sönmez, F. S., & Graefe, A. R. (1998a). Determining future travel behavior from

past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. Journal of Travel

Research, 37(2), 171–177.

Sönmez, F. S., & Graefe, A. R. (1998b). Influence of terrorism risk on foreign

tourism decisions. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 112–144.

Steene, A. (1999). Risk management within tourism and travel suggestions for

research programs. Turizam, 47(1), 13–18.

Stergiou, D., Airey, D., & Riley, M. (2008). Making sense of tourism teaching.

Annals of Tourism Research, 35(3), 631–649.

Stone, R. N., & Grønhaug, K. (1993). Perceived risk: Further considerations for the

marketing discipline. European Journal of Marketing, 27(3), 39–50.

Stone, R. N., & Mason, J. B. (1995). Attitude and risk: Exploring the relationship.

Psychology & Marketing, 12(2), 135–153.

Teng, W. (2005). Risks perceived by Mainland Chinese tourists towards Southeast

Asia destinations: A fuzzy logic model. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research,

10(1), 97–115.

Tesh, S. (1981). Disease causality and politics. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and

Law, 6(3), 369–390.

Tourism Bureau (2007). 2006 annual survey report on R. O. C. outbound travelers.

Taipei: Tourism Bureau.

Tsaur, S.-H., Tzeng, G.-H., & Wang, K.-C. (1997). Evaluating tourist risks from fuzzy

perspectives. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(4), 796–812.

Unser, M. (2000). Lower partial moments as measures of perceived risk: An