as a PDF

advertisement

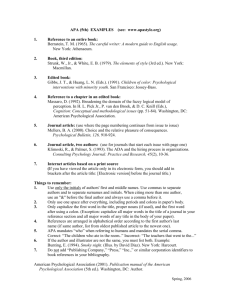

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0143-7720.htm Does one size fit all? Does one size fit all? A study of the psychological contract in the UK working population Carol Atkinson 647 Manchester Metropolitan University Business School, Manchester, UK, and Peter Cuthbert Manchester Metropolitan University – Cheshire, Crewe, UK Received 16 February 2004 Revised 13 December 2004 Accepted 20 December 2005 Abstract Purpose – This paper sets out to investigate the effect of position in the organisational hierarchy on an employee’s psychological contract. Design/methodology/approach – This paper presents a statistical analysis of secondary data taken from the Working in Britain 2000 (WIB) dataset, an ESRC/CIPD funded study, to investigate the perspectives on the content of the psychological contract of different employee groups, namely managers, supervisors and “shop floor” employees. Findings – The results show that differences do emerge between different groups of employee, managers having a generally more relational contract. These differences are not, however, as large as may be expected and, for some aspects of the psychological contract, there are also considerable similarities between all the groups. Research limitations/implications – Analysis is limited by the data present in the dataset, meaning that certain aspects of the psychological contract, for example, trust, are not as fully explored as is desirable. Practical implications – The research has implications for how to appropriately manage the employment relationships of differing employee groups. Originality/value – Most existing empirical data assume that there is “a” psychological contract within an organisation and the findings from this research demonstrate that the position is, in fact, more complex. Keywords Psychological contracts, Intergroup relations, Transactional leadership, United Kingdom Paper type Research paper Introduction In recent years, the psychological contract has achieved prominence as an investigative paradigm within organisational research (Marks, 2001). However, while there is a growing body of research into the psychological contract, there remain key areas that are unexplored. In particular, there is a tendency to describe “the” psychological contract that prevails within an organisation, rather than considering the range of contracts that may exist. This stands in contrast, however, to a body of literature that explores the difference in the experience of work of different groups of employees (see, for example, Collom, 2003; Gallie et al., 2004), and would support the argument that multiple perspectives on the psychological contract in an organisation exist. In this paper, we sets out to investigate the perceptions of the psychological contract by three different employee groups within the organisation using data from the ESRC/CIPD funded study, Working in Britain 2000 (WIB). This particular analysis selects a sub-set International Journal of Manpower Vol. 27 No. 7, 2006 pp. 647-665 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited 0143-7720 DOI 10.1108/01437720610708266 IJM 27,7 648 of questions from the self-completion questionnaires in the study that are deemed to relate to aspects of the psychological contract. The respondents used for the analysis are limited to those who were employed, thus ignoring the self-employed section of the WIB data. It would seem that perceptions of the psychological contract do, indeed, differ by employee group, but that the differences may not be as great as had been anticipated. While managers tend to have a more relational contract than supervisors and employees, the contracts of these latter two groups are not wholly transactional and contain a number of relational obligations. These findings provide an additional insight into managing the employment relationship. The psychological contract There is no broadly agreed definition of the psychological contract construct, the one adopted in this paper being drawn from Guest and Conway (2002) and holding that the contract comprises perceptions of mutual obligations implied within the employment relationship. While this definition suggests that both employer and employee may hold psychological contracts, the dataset used in this study permits investigation of only the employee’s perception of the psychological contract. Guest and Conway (1998) suggest a model around which to build much-needed theory in the psychological contract field which comprises of the causes, content and consequences of the psychological contract. While there is little agreement on the most appropriate way to investigate the psychological contract (Freese and Schalk, 1996), we adopt the content aspect of Guest and Conway’s (1998) model for the purposes of this paper, the content being suggested to comprise of fairness, trust and delivery of the “deal”, i.e. the extent to which obligations are fulfilled. There is little critique of this model in the extant literature, albeit some have argued that trust is an outcome of the psychological contract (Shore and Barksdale, 1998). Other studies, however, have also found that trust is part of the psychological contract (Fox, 1974, Rousseau, 1995) and the model’s origin in a series of well respected CIPD studies and its adoption in other academic studies (see, for example, Martin et al., 1998) lead us to argue for its robustness. The exploration of fairness, trust and delivery of the deal is key to this study and relevant literature is presented in more detail below. Fairness The first element of the content is “fairness”, this equating to consideration of organisational justice. Organisational justice describes the individual’s and the group’s perception of the fairness of treatment received from an organisation and their behavioural reaction to such perceptions (James, 1993). While detailed conceptualisations of organisational justice hold it to be tripartite (Ayree et al., 2002), the limitations of the dataset adopted within this study lead to organisational justice being considered at a general level, rather than in its specific forms. Trust Guest (1998) suggests that trust is the key integrative concept within the psychological contract, the key influence on trust is whether each side (employer and employee) has kept its promises and commitments to each other, i.e. delivered the “deal” (Guest and Conway, 2001). Employees can develop trust in specific individuals, such as supervisor, and generalised representatives such as the organisation (Whitener, 1997). At an organisational level, where much psychological contract research is currently situated, employees hold beliefs and attitudes about a generalised and perhaps anthropomorphic organisation and can develop trust in the organisation itself (Morrison and Robinson, 1997). It is currently suggested that employee expectations develop incrementally in the employment relationship and become embedded in a psychological contract reflecting their beliefs about the nature of the reciprocal exchange agreement between themselves and their employer (Whitener, 1997). Does one size fit all? 649 The “deal” The “deal” refers to the obligations contained within the psychological contract. A range of research has produced a wide array of obligations that are deemed to form the content of the psychological contract and, in common with many other aspects of this construct, there is no clear agreement on these obligations. While Herriot et al. (1997) produce a very detailed set of employee and employer obligations, most writers have aggregated detailed lists of obligations in order to suggest a more succinct description of the deal. Herriot and Pemberton (1996) suggest, for example, job content, job security, training and development, rewards and benefits, and future career prospects. Alternatively, fair pay, good working conditions and job security are proposed by McFarlane Shore and Tetrick (1994). Further research has led to analysis of these obligations and the suggestion that distinct types of employment relationship can be discerned from patterns of employer and employee obligations (Rousseau, 1990). Many have termed these patterns “transactional” and “relational” psychological contracts, indicating the type of obligation contained within each (MacNeil, 1985). Transactional contracts are specific, “monetizable” exchanges between parties over a finite and often brief period of time. Relational contracts are open-ended less specific agreements that establish and maintain a relationship (Robinson et al., 1994). Although it is not always clear which obligations belong to which category (Arnold, 1996), Rousseau’s (1990) description of transactional and relational obligations may be expressed diagrammatically in Figure 1. Thus, the deal can be considered as having elements of both transactional and relational features and being on a continuum, rather than being wholly of one type or the other (Coyle-Shapiro and Kessler, 2000), a perspective already established in the literature on relationship marketing (e.g. Buttle, 1996). It should be noted, however, that there is particular debate as to whether advancement should be categorised as a transactional obligation, viewing it from a career resilient perspective (Rousseau, 1990) Figure 1. Employer obligations IJM 27,7 or whether it should be categorised as relational, viewing it from an organisationally based career perspective (Stiles et al., 1997). This is a point to which we return later in the paper. Having established the theoretical basis from which this study investigates the psychological contract, we now turn to consider how perspectives on the contract may vary by employee group. 650 One psychological contract? Much of the available research, rather than considering the issue of varying content, suggests that the content of the psychological contract in the UK is general across most workers. Herriot et al.’s (1997) study, for example, identifies few differences in content between various categories of employees and, similarly, the CIPD studies suggest that differences between such groups are not considered significant (see, for example, Guest et al., 1996; Guest and Conway, 1997). One Belgian study (Sels et al., 2000) presents findings indicating that white- and blue-collar workers have very different psychological contracts, but attributes this to specific labour laws that apply in Belgium. Some consideration has been afforded to differing employee groups with a variety of findings. Freese and Schalk (1996) investigated the psychological contracts of full-time versus part-time employees, finding few differences between the two groups. In investigating the psychological contracts of temporary staff, McDonald and Makin (2000) demonstrated that the contracts of permanent and temporary staff did not differ significantly, a finding supported by consideration of psychological contracts in the financial services sector (Sparrow, 1996). Other studies have implicitly recognised the possibility of differing psychological contracts in discrete groups of workers. King (2000) for example, investigated white collar reactions to job insecurity and Flood et al. (2001) explored the causes and consequences of the psychological contract in knowledge workers. What remains largely unexplored, however, is possible differences among the content of psychological contracts dependent on place in the organisational hierarchy, the focus in a hierarchical context being on the impact of a changing employment relationship on the managerial or professional psychological contract (see, for example, Atkinson, 2002). It is argued in this literature that a shift has occurred in such contracts from an “old” relational contract to a “new” more transactional contract (Hiltrop, 1996) in which there have been reductions in job security and career progression and a shift to a career resilient approach. The literature is largely silent on the impact of such changes on non-managerial/non-professional employee groups, albeit one US study suggested that relational contracts have diminished across all employee groups (De Meuse et al., 2001). Another study indicates that supervisors are slightly likely to have a more relational contract than other employees (Freese and Schalk, 1996), while Herriot et al.’s (1997) findings suggest that the nature of the employee psychological contract is fundamentally transactional. There is, therefore, no consensus in this area. Further, while Guest and Conway’s (1998) model of the psychological contract does not explicitly consider transactional/relational issues, their large scale surveys of a range of employee groups suggest that the degree of change in the psychological contract has been exaggerated (Guest and Conway, 1999) and that traditional psychological contracts are still widely to be found. Thus there are contradictions and omissions in the extant literature: it is unclear to what extent the managerial psychological contract has become less relational and there is little evidence on how this contract compares to the contract of a “shop floor” worker. The focus of this paper, therefore, is to investigate the extent to which psychological contracts vary across employee groups in the UK, this also potentially giving insight into whether relational or transactional contracts dominate in the contemporary employment relationship. In seeking to theorise why employee groups may hold varying psychological contracts, we draw on motivation theory, considering Herriot et al.’s (1997) study which presents transactional obligations as hygiene factors (Herzberg et al., 1959), which must be fulfilled prior to the development of relational obligations, which constitute motivational factors. Herriot et al.’s (1997) study identifies pay and safe working hours and conditions, transactional obligations, as the main focus for employees, suggesting that managers under-estimate the importance of such obligations and focus to a greater extent on relational obligations. Sels et al. (2000) also present transactional obligations such as pay as being fundamental within a blue collar contract, white collar contracts being predicated on relational obligations such as job security and career progression. The validity of Herzberg’s theory of motivation has been recently reaffirmed (Brislin et al., 2005) and, while this study does not explicitly adopt a psychological contract framework, it compares the impact of different aspects of the employment relationship on the motivation of Japanese managers and employees in terms that can be interpreted as obligations within the psychological contract. For example, Brislin et al., (2005) suggest that pay and working conditions, transactional obligations, are key within the employee psychological contract, and again that managers under-estimate the importance of these to employees and over-estimate the importance of relational obligations such as job advancement. Such findings lead to the inference that it is more likely that managers will have relational contracts than employees. Acceptance of such a proposition may, however, be controversial, ignoring as it does the debate in the literature as to the extent that pay actually motivates employees (Armstrong, 2002) and the argument that employees at all levels are motivated by aspects of the job such as responsibility and interesting work (Morse, 2003). What is clear, however, is that literature in this area does not reflect the varying work experiences of different employee groups in the way that other bodies of literature do, for example, job satisfaction (Rose, 2003) and autonomy (Collom, 2003). We argue that this is an area in need of further investigation. We need also to consider the implications for the other two elements of the content of the psychological contract, trust and justice (Guest and Conway, 1998). Rousseau (1995) argues that trust is part of a relational contract only, so it may be inferred that employees with a transactional contract have either low or non-existent trust in their employing organisation. It might also be expected that managers in a relational contract would have higher levels of trust, although this may be impacted on by changes that are argued to have been wrought to their contracts. Finally, it may be that employees have lower expectations of being fairly treated within a transactional contract: they hold little power in comparison to managers, may not anticipate interactional justice in a transactional contract and may even perceive that distributive justice is limited if dissatisfied with their pay. In summary, we draw on limited empirical data that suggests that employees are more likely to have transactional psychological contracts and managers relational Does one size fit all? 651 IJM 27,7 contracts, although we recognise the contentious nature of this proposition and argue the need to investigate it more fully in relation to obligations, trust and justice within the content of the psychological contract. Findings supporting this proposition will clearly have significant implications for a high commitment HRM agenda that seeks to win “hearts and minds” in order to harness employee commitment and is likely to founder in the face of an employee focus on overwhelmingly transactional issues. 652 The data source and survey population This study of the psychological contract draws data from the Working in Britain 2000 (WIB) survey, an ESRC/CIPD funded study. The WIB survey presents data gathered as part of a detailed investigation into various aspects of the contemporary employment relationship in the UK. A key aspiration of the WIB study is that it is representative of all working groups in the UK. The respondents comprise the employed, the self employed, workers, managers, supervisors and “shop floor” employees. The focus within the study reported in this paper, however, is somewhat narrower. It seeks to address issues relating to the psychological contract for respondents that have employed status. The self-employed group in the WIB data, while probably an interesting group in themselves, have been omitted for the purposes of this analysis. In order to facilitate investigation of the issues outlined above, it has been necessary to reduce the data within the dataset just to employed respondents. This subsection of respondents comprises 87.5 per cent of the original data. In the context of the WIB dataset and based on the above discussion drawn from extant literature, the proposition is that perceptions of the psychological contract will differ between the different groups of employees: managers, supervisors and employees. Thus the sub-set identified above has been re-coded generating a new variable that identifies three employment groupings: (1) manager; (2) supervisor; and (3) employee. While the focus is on the employment groups of manager, supervisor and employee, the data were also controlled for issues of age and gender (no data being available in respect of ethnicity). Using a Mann-Whitney U test for two independent samples in respect of gender, no significant differences were detected in the sample in relation to gender when considering either fairness or the deal. Kruskal Wallis tests, however, reveal that age produces significant variances in both fairness and, to a lesser extent, the deal. It is argued, however, that consideration of such issues is outwith the scope of this study. Sample design issues The User Guide for the WIB survey states that the intention is to achieve a sample that, “should allow an achieved national sample of 2,500 with a nationally representative sample of the employed population in Great Britain aged between 20 and 60” (User Guide 10, p. 3), using postcode sectors as primary sampling units, and selecting a total of 167 sectors. It also states that this objective has been achieved with a final screened sample of 2,465 respondents representing an overall response rate of 64.6 per cent, further descriptives of the sample being available in the WIB User Guide. On the basis of the information provided in the User Guides, the data are deemed appropriately representative of the current workforce in Britain. Does one size fit all? Identifying the psychological contract in the WIB dataset As explained earlier, Guest and Conway (1998) suggest that the three key elements of the content of the psychological contract for employees are fairness, trust and delivery of the deal. In order to operationalise these elements, the self-completion questionnaires in the WIB survey were considered and questions identified that appeared to reflect relevant aspects. The WIB survey questionnaire adopts a single scale approach to measurement, asking the extent to which obligations have been fulfilled or not. For the first element, fairness, each of the questions chosen for use in this study is shown below with its original question number and full text. The first question number relates to the question position in the non-managerial questionnaire, while the second number relates to its position in the managerial questionnaire (Table I). It is argued that these questions are valid in operationalising fairness in that they reflect anxiety (a perceptual state) about a range of unfair treatment, from dismissal to victimisation to bullying. These issues do, however, relate largely to an interactional form of justice, and investigation of other aspects of justice, which would enhance the analysis, is not possible based on the adopted dataset. The selected questions were subjected to factor analysis to identify the underlying constructs. A two-factor model emerged in which all the obligations items and trust formed one factor, while the fairness items formed a second factor. Cronbach Alpha was calculated for the two scales. The Alpha value of 0.9251 for the five items of the fairness scale is considered adequate. The second element of the psychological contract considered is “trust”. For this, just one indicator question that concerns trust in the employer to keep commitments made (Table II) was identified. It is recognised that a single item measuring trust creates 653 Variable Fairness Fairnes1 Fairnes2 Fairnes3 Fairnes4 Fairnes5 Q. 8/12 How anxious are you about these situations affecting you at your work? Being dismissed without good reason Being unfairly treated through discrimination Victimisation by management Bullying Sexual harrassment Variable Trust Trust1 Q.15/19 Overall, how much do you trust your employer to keep their promises or commitments to employees? Table I. Original questions from the Working in Britain 2000 survey used to consider “fairness” Table II. Original questions from the Working in Britain 2000 survey used to consider “trust” IJM 27,7 654 limitations in respect of the findings for this element of the content of the psychological contract. The third element of the psychological contract considered is the “deal”. This has been analysed using indications of commitments from the employer regarding features of the employment relationship and it is argued that this is a satisfactory operationalisation of the deal as such commitments can be argued to be obligations that are based on promises from employer to employee (Rousseau, 1995). Again all the items used are from the self-report section of the questionnaire. The specific questions selected for this study, in their original form, are shown in Table III. The Cronbach Alpha for these 11 items is 0.9327 which is again deemed to be adequate in order to consider these items as a scale. Although factor analysis produced a two factor model which conflated obligations and trust, removing the “trust” item from the obligations scale improves the alpha value to 0.9346. All the variables available for this analysis have yielded ordinal data, and the sub-groups within the sample are of different sizes. So, in order to investigate differences between the groups, the Kruskal-Wallis One-way ANOVA (K-W) by ranks has been used. Similarly, the median is deemed to be the most appropriate measure of central tendency with these data. While other statistics such as quartile points could have been used to analyse these data in greater detail, such analysis has not been included due to the limitations of space of this paper. For the analysis, the proposition that perceptions of the psychological contract will differ between the different groups of employees has been rendered into the following generic hypotheses: H0. The groups are drawn from the same population, so there is no difference between the median scores of managers, supervisors and employees for the particular variable. H1. The groups are drawn from different populations and so differ with respect to the median scores for the particular variable. Table III. Original questions from the Working in Britain 2000 survey used to consider the “deal” Variable The deal Deal1 Deal2 Deal3 Deal4 Deal5 Deal6 Deal7 Deal8 Deal9 Deal10 Deal 11 Q.14/18 Some of the commitments that employers make to their employees are written down in contracts or “terms and conditions”, others are verbal promises or understandings. Below are a list of commitments that your employer may have made, and for each I would like you to indicate to what extent you think they have kept that commitment (a) To give you the training you need to do your job well (j) To offer you flexibility or choice over your working hours (j) To reward good job performance (b) To provide a decent working environment (d) To provide long-term job security (e) To give you chances for promotion within the organisation (f) To provide challenging work (g) To train you in skills you can use if you leave (h) To provide pay rises to maintain your standard of living (i) To provide time off for family requirements (b) To be fair in the application of rules Findings Fairness Given that the items selected to assess the issue of fairness are deemed to form a scale, an overall rating for respondents has been calculated, using the median rating. Next, the hypothesis of a difference in the overall rating for fairness between managers, supervisors and employees is investigated using the Kruskal-Wallis One-way ANOVA test. The result suggests that the differences between patterns of responses of the groups are significant (p ¼ 0:033), as shown in Table IV. It is interesting to notice that, while the proportional patterns of rating are very similar, the employees show a greater level of anxiety than mangers. Those falling into the two anxious categories form 17 per cent for employees and 12 per cent for managers. The next section considers the items comprising the Fairness Scale individually. Two of the five variables show statistically significant differences between the three groups. For the first variable (Table V), “Dismissal without good reason”, the Kruskal-Wallis test result is significant (p ¼ 0:003) and the cross tabulation clearly shows the difference between the managers and the other two groups. It is of note that only half the respondents claim not to be anxious about unfair dismissal, and that more than a quarter of supervisors and employees have chosen the two most anxious categories. For the second variable, “Anxiety about discrimination”, the K-W test suggests that there are significant differences (p ¼ 0:001) but in this case the overall level of anxiety appears to be slightly lower. Over 20 per cent of supervisors and employees describe themselves as very or fairly anxious about discrimination, with once again the pattern of much lesser anxiety by managers (12.4 per cent in these two categories) showing up clearly. For the third and fourth variables, “Anxiety about victimisation” and “Anxiety relating to bullying”, the differences between the groups are not statistically significant (p ¼ 0:170), although managers continue to show somewhat lesser anxiety than the other groups. Despite this, around 13 per cent of supervisors and employees are concerned about bullying in the workplace. Managers Supervisors Employees Managers Supervisors Employees Very anxious (%) Fairly anxious (%) Not very anxious (%) Not at all anxious (%) Total (%) 4.6 6.3 8.4 7.0 7.1 8.7 25.4 24.7 25.3 63.0 61.9 57.6 100.0 100.0 100.0 Very anxious (%) Fairly anxious (%) Not very anxious (%) Not at all anxious (%) Total (%) 5.9 13.5 11.7 9.7 13.5 13.7 27.3 23.9 23.6 57.1 49.1 51.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 Does one size fit all? 655 Table IV. Perceptions of anxiety about an employer’s fairness (median rating) cross-tabulation Table V. Perceptions of anxiety about dismissal without good reason (fairnes1) cross-tabulation IJM 27,7 The fifth variable, “Anxiety about sexual harassment”, does not yield a statistically significant difference (p ¼ 0:350). However, the cross tabulation in Table VI still shows that proportionately fewer managers are anxious about the issue. Taken overall, the pattern of responses seems to suggest that respondents who are managers are less anxious and have a greater perception of fairness in their psychological contract than for the other two groups. 656 Trust For the single item chosen to represent views on the issue of trust, a similar approach is adopted to that used with the fairness scale. A hypothesis of a difference between the groups is investigated using the Kruskal-Wallis One-way ANOVA test. In this case, the result shows similar medians, and the differences between the groups appear not to be significant (p ¼ 0:049), as shown in Table VII. For Table VII, the pattern of responses for the three groups appears to be very similar. Only one-third of all the groups place a high level of trust in their employer. A further third show some trust in their employer while the remaining third have little or no trust. The pattern of employees being the most pessimistic and managers being the most optimistic about their employer, first identified for Fairness, is repeated here, but the differences are very small and not significant. The deal Once more a similar approach is adopted in relation to the eleven items comprising the deal scale. The hypothesis of a difference between the groups is investigated using the Kruskal-Wallis One-way ANOVA test. Table VIII relates to the average responses for the scale over the eleven items. In this case the differences between the groups are significant (p ¼ 0:000). In the case of Table VIII, it is clear that the pattern of responses for employees suggests that they have a rather lower belief in the possibility that their employer will honour “the deal”. Nearly twice the proportion of employees feel that the employer has made no commitment while at the opposite end of the scale, employees are the smallest Table VI. Perceptions of anxiety relating to sexual harassment cross-tabulation Table VII. Perceptions of levels of trust in employer to keep promises Managers Supervisors Employees Managers Supervisors Employees Very anxious (%) Fairly anxious (%) Not very anxious (%) Not at all anxious (%) Total (%) 3.0 6.6 6.4 1.9 3.6 2.9 19.9 19.4 16.3 75.1 70.4 74.3 100.0 100.0 100.0 A lot (%) Somewhat (%) Only a little (%) Not at all (%) Employer makes no commitment (%) Total (%) 35.7 34.4 33.1 43.5 35.1 38.2 12.4 18.7 17.1 5.6 7.6 6.9 2.8 4.2 4.8 100.0 100.0 100.0 group to think that the employer has done extremely well. This contrasts strongly with the pattern of responses for Table VII that relates to perceptions of levels of trust in the employer to keep promises. These differences relate perhaps to the average pattern of responses of 11 relatively different aspects. For Table VIII, it appears to be managers that hold the most different views to supervisors and employees. The distribution of their responses suggests that they feel that the employer has delivered more on the deal in comparison to the two other groups. The transactional-relational perspective. Categories of transactional and relational obligations within the psychological contract were outlined earlier in this paper (see Figure 1). These are reflected by the following questions from the WIB survey data (Table IX). The three variables identified as relating to a transactional view of the psychological contract, and the five items that are considered to relate to the relational view have been subjected to the Cronbach Alpha procedure. For both the transactional items and the relational items, the resulting Alpha values are less than 0.6, and thus it has been decided that the variables cannot be treated as scales. For this reason the variables will be considered individually. For the three transactional variables, “Good promotion prospects”, “Good pay” and “Extra reward for performing well”, a hypothesis of a difference between the three groups has been tested using the Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA procedure. In the case of question 2, Promotion, and question 3, Pay, a significant difference is identified (p ¼ 0:000, p ¼ 0:008), but for “Extra reward” there appears to be no significant difference between the groups. To simplify Table X the latter variable has been omitted. Managers Supervisors Employees Element Extremely well (%) Very Well (%) 12.4 13.4 10.2 36.3 27.9 27.9 Fairly well (%) Not very well (%) No commitments made (%) Total (%) 31.9 34.7 34.5 10.3 15.6 11.4 9.1 8.4 15.9 100.0 100.0 100.0 Does one size fit all? 657 Table VIII. Managers, supervisors and employee’s ratings of their employer’s commitment to keeping their side of the “deal” – median rating cross-tabulation Question B1 I am going to read out a list of things people may look for in a job and I would like you to tell me from this card how important you feel each one is to you when looking for a job Transactional Advancement High pay Merit pay Relational Training Job security Development Development Support 2. Good promotion prospects 3. Good pay 11. Extra reward for performing well 9. Good training provision 5. A secure job 6. A job where you can use your initiative 8. The opportunity to use your abilities 12. Hours of work that leave time for family or leisure Table IX. WIB Survey questions considered to relate to transactional versus relational views of work obligations IJM 27,7 Issue 658 (2) Good promotion prospects Managers 19.6 Supervisors 12.3 Employees 11.7 (3) Importance Managers Supervisors Employees of good pay 29.0 36.8 28.7% Table X. Perceptions of the importance of key transactional and relational aspects of the job Fairly important (%) Not very important (%) Do not know (%) 43.8 49.1 33.5 28.1 29.4 35.4 8.3 9.3 18.8 0.2 0.0 0.6 45.1 45.7 47.4 24.2 15.2 22.1 1.5 1.9 1.6 0.2 0.4 0.2 (9) Importance Managers Supervisors Employees of good training 21.4 46.2 28.6 49.8 24.7 47.5 27.0 18.2 22.1 5.4 3.3 5.2 0.0 0.0 0.5 (5) Importance Managers Supervisors Employees of a secure job 29.8 35.3 33.7 43.8 52.4 50.8 20.5 10.8 12.3 5.4 1.5 2.8 0.4 0.0 0.4 (6) Use initiative in your job Manager 27.9 Supervisors 20.1 Employees 18.3 59.7 62.5 54.0 11.5 16.4 25.3 0.7 1.1 1.8 0.2 0.0 0.6 (8) Use abilities Managers Supervisors Employees 56.6 55.4 56.4 7.4 16.4 18.2 0.9 1.5 1.2 0.0 0.3 0.3 time for family 33.8 39.4 37.2 43.5 37.0 45.3 21.8 15.6 14.9 4.6 3.7 2.5 0.4 0.0 0.0 (12) Job allows Managers Supervisors Employees Essential (%) Very important (%) in your Job 35.1 26.4 23.9 In Table X, promotion prospects are clearly more important to managers and supervisors of whom more than 60 per cent chose the top two categories. By comparison only 45 per cent of employees chose the top two categories, with most of their responses being in the lower importance categories. It should be noted that, given the debate in the literature about the appropriate categorisation of promotion, it is possible to argue that this finding lends weight to the suggestion that promotion should indeed be viewed as a relational obligation, forming part of the manager’s contract more often than an employee’s contract. Good pay (Table X) appears to be more important to supervisors of whom 82 per cent chose the top two categories, compared to employees and managers of whom around 75 per cent chose those responses. The results shown in Table X would seem to suggest that for employees, the transactional elements of promotion and pay are rather less important than for managers and supervisors. For the five questions that are considered to represent the relational view of the psychological contract, the K-W tests suggests that a significant difference is found to exist between the three groups (Q 9, p ¼ 0:005, Q 5, p ¼ 0:000, Q 6, p ¼ 0:000, Q 8, p ¼ 0:000, Q 12, p ¼ 0:012). The patterns of responses for each item will be considered below. It is clear from Table X that all groups consider training to be important with more than two-thirds of all respondents choosing one of the top two ratings. However, the supervisors group shows a significantly higher emphasis than the other two groups. A secure job is considered to be highly important with more than 70 per cent of all the respondents choosing one of the top two categories. However, Supervisors are in the majority with 88 per cent of that group choosing these two rating points, compared to managers of whom only 74 per cent chose one of the two highest categories. The three patterns for the question, Importance of a Job where you can use your initiative, take the shapes that might have been expected with managers showing the greatest preference, followed by supervisors, with employees coming lowest. However, lowest is a relative term, and it should be noticed that more than 72 per cent of employees chose one of the top two categories. This would seem to suggest that a significant proportion of all employees would like to be able to use their initiative at work. The question about “Opportunities to use your abilities” is similar to, but slightly different from, the question about initiative. However, the patterns of preferences are similar with managers having the highest proportion of responses in the top two categories, and employees having the least. Once again, employees clearly want to make use of their abilities with 80 per cent of these respondents choosing one of the top two categories. In relation to the issue of support, the WIB question on time for family is selected. This is deemed to be the most closely related issue within the data. In this case, both employees and supervisors show very similar patterns of responses. For both groups, more than 82 per cent of respondents selected one of the two most important categories of response. However, the managers group showed fewer responses in the top two categories, although these respondents represented more than 72 per cent of their group. Overall, this examination of the transactional and relational aspects of the psychological contract shows that, for the most part there are significant differences between the views of managers, supervisors and employees. For the transactional aspects, promotion is more important to managers and supervisors than to employees. Similarly, whilst all groups believe that good pay is important, supervisors rate this more highly than other groups. For the relational aspects, supervisors rate training, and also a secure job more highly than the other two groups. For the issue of “Using initiative”, as might be expected, managers rate this most highly, followed by supervisors and then employees. However, for this issue more than two-thirds of employees thought it at least very important. A similar picture emerged in relation to “Using abilities”, but in this case more than 80 per cent rated this issue at least very important. For support, as measured by the importance placed on time with the family, managers rated this less important than employees or supervisors. However, more than 70 per cent of managers felt this issue to be at least very important. Does one size fit all? 659 IJM 27,7 660 Discussion This paper has set out to investigate an identified gap in empirical data: to what extent the psychological contracts of employees differ dependent on their place in the organizational hierarchy. Significant differences in the salience of the differing parts of the contract by employee group are evidenced, but also there are considerable areas of similarity. The above findings present an interesting insight into the psychological contract. The statistical analysis of the WIB dataset provides, via factor analysis of the items extracted, support for the model of the psychological contract adopted in this study. Factor analysis suggests a two-factor model, fairness and obligations, trust being included with obligations. Removing trust from obligations would, however, make this factor more robust and it is argued that, were more data available on trust, this might emerge as the third factor. The findings also contribute to the current debate as to the “state” of the psychological contract (Atkinson, 2002). It is questioned whether there is a positive, trusting relationship between organizations and their employees, as some would suggest (Guest and Conway, 1999), or whether the psychological contract has been degraded by continuous change leaving employees feeling insecure and dissatisfied as suggested by others (Robinson and Morrison, 2000). The findings from this study would seem to support the argument that a reasonably positive psychological contract exists. For example over 80 per cent of all employees have low levels of anxiety about unfair treatment, over 70 per cent of all employees have some or a lot of trust in the employer to keep promises and over 70 per cent of employees believe that employers will honour their commitments at least reasonably well. However, the results at a more specific level, suggest that the “positive psychological contract” is, perhaps, an over-optimistic reading of the data. In terms of fairness, significantly more employees are anxious about unfair treatment than are managers and this is especially so with reference to dismissal without good reason and discrimination. The levels of anxiety are somewhat surprising (25 per cent for employees, 21 per cent for managers), especially given employment legislation that is intended to regulate these issues and would suggest that there is significant scope for improvement in the employment relationship. Additionally, 13 per cent of supervisors and employees are concerned to some degree about bullying. These data consider only the content of the psychological contract, but the outcomes of the contract cover issues such as motivation, satisfaction, organizational citizenship behaviour and intention to quit (Guest and Conway, 1998) and thus the impact on these issues on lack of perceived fairness among a fair subsection of employees must be of concern. Issues relating to trust are assessed on the basis of only one item and it seems somewhat surprising that this construct is not more rigorously investigated within the WIB study. While there are no significant differences demonstrated between the different groups, it is interesting to note that only one-third of all employees place a lot of trust in their employer to keep promises. This supports evidence from elsewhere (Guest and Conway, 2001) and, again in terms of the outcomes of the psychological contract, raises concerns about the robustness of the employment relationship. It is, however, apparently at odds with the data presented concerning ratings of the respondents’ belief that their employer is committed to keeping its side of the “deal”. The patterns observed for the scale of the “deal”, that is the belief of employees that the employer will honour its commitments, are similar to those described for fairness. Managers seem to have greater belief in the employer’s intention to honour the deal than do supervisors and employees. This is especially so in terms of the items relating to promotion, pay, training, job security, use of initiative and ability and work/life balance (i.e. all except reward). The rhetoric of HRM suggests that employers should strive to develop a relational contract in order to win “hearts and minds” and, in harnessing commitment, thus drive high performance (Guest and Conway, 2001). This focus on relational issues has, however, been called into question (Herriot et al., 1997) by suggestions that employers are in danger of underestimating the fundamentally transactional nature of the employment relationship. The broad findings of this paper would appear to tentatively support the argument that employee groups other than managers, i.e. supervisors and employees, are less likely to have relational contracts and that their more transactional contracts are likely to incorporate perceptions of lower levels of justice and less trust. However, the patterns of and absolute data presented here do not support the view that for many employees the employment relationship is wholly transactional. While it is true that, in terms of patterns, managers and supervisors seem to place more value on many of the relational issues, employees do not place a higher value on the transactional issues. Indeed the one issue on which they place more importance than the other two groups is a relational one. In terms of absolute data, the levels of importance placed on both relational and transactional issues are high for all groups, demonstrating the salience of these issues across all employees. What does emerge clearly from the data is that managers have greater perceptions of being treated fairly by the employer and a greater belief that the employer will honour its commitments, seeming thus to trust the employer more, despite the limited data on trust itself. The probable implications of these results are that the facets of the psychological contract are more complex than the simplistic continuum model shown in Figure 1. Despite a model suggesting that trust, fairness and obligations are part of the content of the psychological contract, most extant data on transactional and relational issues adopts an obligations-only based perspective. We argue that incorporating considerations of trust and justice into the debate gives a more rounded perspective on transactional and relational aspects of the psychological contract and aim to open this debate with the findings presented in this paper. It seems clear that all employees want to be challenged and developed although to a different degree depending on their place in the organisation. The challenge then for line managers and HRM is to develop policies and practices that meet the needs of the different employee groups, it appearing possible to move beyond a wholly transactional psychological contract for all employee groups and to strive towards a “committed” workforce at all levels. Conclusions In this research, we set out to investigate the psychological contract using the WIB survey data. It has emerged that there are differences between the employee groups, represented in the survey, in relation to their perceptions of the contract. Managers appear to have a more “positive” take on the psychological contract than the other two groups. However, in key elements of the deal, such as use of initiative, the other two Does one size fit all? 661 IJM 27,7 662 groups are not far behind managers in their importance ratings. Supervisors have also been shown as a group with quite different perspectives for many of the obligations examined. The research has also highlighted an interesting difference between respondents rating of the single Trust item, and the lower ratings for the aggregated deal scale. Overall, it seems safe to conclude that it would not be sensible to postulate a single “vision” of the psychological contract that is applicable to all employees, although the findings here do not give clarity to the exact differences between the groups. It is argued that a fuller consideration of the elements of the content of the psychological contract might usefully inform this debate. In adopting a secondary data set as the basis for analysis, this study has necessarily faced limitations, not least in considering the element of trust, for which there is only a single item. Further, the single scale approach used in the survey questionnaire requires employees to respond as if employers have given commitment on certain issues and makes no provision for if this is not the case, the advantage of a two scale method which asks first if the commitment has been made, and then whether it has been fulfilled. The questionnaire also explores justice to a limited extent, the focus being on interactional rather than distributive or procedural. Finally, the employee perspective is provided, but there is no insight into the employer perspective, which would provide a fascinating contrast. Further research should investigate this notion of a variety of psychological contracts by employee group, considering the implications of this for a whole range of issues relating to the management of the employment relationship. It is also suggested that fuller exploration of the significance of age on the psychological contract would make a useful contribution to the understanding of this construct. More detailed consideration of the elements of trust and justice within the psychological contract would provide further valuable insights. Finally, it is worth noting that the data set provides a perspective on the employment relationship in the UK which is likely to be context specific. Comparative studies of the employment relationship are also likely to provide useful, contrasting data. References Armstrong, M. (2002), Employee Reward, CIPD, London. Arnold, J. (1996), “The psychological contract: a concept in need of closer scrutiny?”, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 5 No. 4, pp. 511-20. Atkinson, C. (2002), “Exploring the state of the psychological contract: the impact of research strategies on outcomes”, paper presented at Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development Professional Standards Conference, University of Keele. Ayree, S., Budhwar, P.S. and Chen, Z.X. (2002), “Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: test of a social exchange model”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 267-85. Brislin, R.W., Macnab, B., Worthley, R., Kabigting, F. Jr and Zukis, B. (2005), “Evolving perceptions of Japanese workplace motivation: an employee-manager comparison”, International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 87-105. Buttle, F. (1996), “Servqual: review, critique, research agenda”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 30 No. 1, pp. 8-32. Collom, E. (2003), “Two classes, one vision?”, Work and Occupations, Vol. 30 No. 4, pp. 62-96. Coyle-Shapiro, J. and Kessler, I. (2000), “Consequences of the psychological contract for the employment relationship: a large scale survey”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 37 No. 7. De Meuse, K.P., Bergmann, T.J. and Lester, S.W. (2001), “An investigation of the relational components of the psychological contract across time, generation and employment status”, Journal of Managerial Issues, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 102-18. Flood, P.C., Turner, T., Ramamoorthy, N. and Pearson, J. (2001), “Causes and consequences of psychological contracts among knowledge workers in the high technology and financial services industries”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 12 No. 7, pp. 1152-65. Fox, A. (1974), Beyond Contract: Work, Power and Trust Relations, Faber & Faber, London. Freese, C. and Schalk, R. (1996), “Implications of differences in psychological contracts for human resource management”, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 5 No. 4, pp. 501-9. Gallie, D., Felstead, A. and Green, F. (2004), “Changing patterns of task discretion on Britain”, Work, Employment and Society, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 243-66. Guest, D. (1998), “Is the psychological contract worth taking seriously?”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 19 No. 6, pp. 649-64. Guest, D. and Conway, N. (1997), Employee Motivation and the Psychological Contract, Institute of Personnel and Development, London. Guest, D. and Conway, N. (1998), Fairness at Work and the Psychological Contract, Institute of Personnel and Development, London. Guest, D. and Conway, N. (1999), How Dissatisfied Are British Workers? A Survey of Surveys, Institute of Personnel and Development, London. Guest, D. and Conway, N. (2001), Organisational Change and the Psychological Contract, Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, London. Guest, D. and Conway, N. (2002), “Communicating the psychological contract: an employer perspective”, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 22-38. Guest, D., Conway, N., Briner, R. and Dickman, M. (1996), The State of the Psychological Contract in Employment, Institute of Personnel and Development, London. Herriot, P. and Pemberton, C. (1996), “Contracting careers”, Human Relations, Vol. 49 No. 6, pp. 757-90. Herriot, P., Manning, W.E.G. and Kidd, J.M. (1997), “The content of the psychological contract”, British Journal of Management, Vol. 8, pp. 151-62. Herzberg, F., Mausner, B. and Snyderman, B. (1959), The Motivation to Work, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. Hiltrop, J. (1996), “Managing the changing psychological contract”, Employee Relations, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 36-49. James, K. (1993), “The social context of organisational justice: cultural, intergroup and structural effects on justice behaviours and perceptions”, in Cropanzano, R. (Ed.), Justice in the Workplace: Approaching Fairness in Human Resource Management, Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. King, J.E. (2000), “White-collar reactions to job insecurity and the role of the psychological contract: implications for human resource management”, Human Resource Management, Vol. 39 No. 1, pp. 79-92. Does one size fit all? 663 IJM 27,7 664 McDonald, D.J. and Makin, P.J. (2000), “The psychological contract, organisational commitment and job satisfaction of temporary staff’”, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, Vol. 21 Nos 1/2, pp. 84-92. McFarlane Shore, L. and Tetrick, L.E. (1994), “The psychological contract as an explanatory framework in the employment relationship”, in Cooper, C.L. and Rousseau, D.M. (Eds), Trends in Organizational Behaviour, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester. MacNeil, I.R. (1985), “Relational contract: what we do and do not know”, Wisconsin Law Review, pp. 483-525. Marks, A. (2001), “Developing a multiple foci conceptualisation of the psychological contract”, Employee Relations, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 454-67. Martin, G., Staines, H. and Pate, J. (1998), “Linking job security and career development in a new psychological contract”, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 20-40. Morrison, E.W. and Robinson, S.L. (1997), “When employees feel betrayed: a model of how psychological contract violation develops”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 226-56. Morse, G. (2003), “Why we misread motives”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 18 No. 1, p. 18. Robinson, S.L. and Morrison, E.W. (2000), “The development of psychological contract breach and violations: a longitudinal study”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 21, pp. 525-46. Robinson, S.L., Kraatz, M.S. and Rousseau, D.M. (1994), “Changing obligations and the psychological contract: a longitudinal study”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 37 No. 1, pp. 137-52. Rose, M. (2003), “Good deal, bad deal? Job satisfaction in occupations”, Work, Employment and Society, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 503-30. Rousseau, D.M. (1990), “New hire perceptions of their own and their employer’s obligations: a study of psychological contracts”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 11, pp. 389-400. Rousseau, D.M. (1995), Psychological Contracts in Organizations, Sage, London. Sels, L., Janssens, M., Van den Brande, I. and Overlaet, B. (2000), “Belgium: a culture of compromise”, in Rousseau, D.M. and Schalk, R. (Eds), Psychological Contracts in Employment: Cross-National Perspectives, Sage, London. Shore, L.M. and Barksdale, K. (1998), “Examining degree of balance and level of obligation in the employment relationship”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 19 No. 6, pp. 731-44. Sparrow, P. (1996), “Transitions on the psychological contract: some evidence from the banking sector”, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 6 No. 4, pp. 75-92. Stiles, P., Gratton, L., Truss, C., Hope-Hailey, V. and McGovern, P. (1997), “Performance management and the psychological contract”, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 57-66. Whitener, E.M. (1997), “The impact of human resource activities on employee trust”, Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 7 No. 4, pp. 389-404. Further reading Harris, L. (2000), “Employment regulation and owner-managers in small firms: seeking support and guidance”, Journal of Small Business and Entreprise Development, Vol. 7 No. 4, pp. 325-62. About the authors Carol Atkinson is a Senior Lecturer in HRM at Manchester Metropolitan University Business School. The psychological contract was the focus of her doctoral thesis and she has subsequently gone on to develop other areas of psychological contract research, adopting both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Her other areas of research are the employment relationship in the small firm and working time flexibility. Carol Atkinson is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: c.d.atkinson@mmu.ac.uk Peter Cuthbert is a Senior Learning and Teaching Fellow and Senior Lecturer in Quantitative Techniques and Research Methods at Manchester Metropolitan University – Cheshire. Peter’s general research interests are relationship marketing, service quality, quality assurance and consumer decision making in higher education, health and other services. He is currently researching student retention and attitudes to and use of e-learning resources. To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints Does one size fit all? 665 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.