Electronic Data Capture In Clinical Trials

advertisement

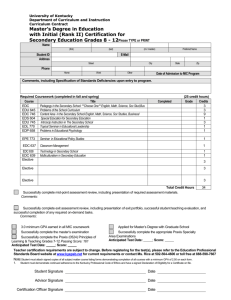

Source Journal for Clinical Research Excellence Issue 82 A Publication of the Society of Clinical Research Associates 530 West Butler Avenue, Suite 109 Chalfont, PA 18914 USA November 2014 ISSN 1536-9900 Highlights - In this issue........... Self Study Opportunity - FDA Guidance for Industry: Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Approval of Human Drugs and Biological Products Clinical Preparation and Defined Roles Increase Data Collection Quality and Result Integrity in Metastatic Thyroid Cancer Trials Project Management: Introduction to Tools and Templates Preserving Integrity in Clinical Research: Avoiding Research Misconduct Effort and Complexity Tracking Metrics in Cancer Clinical Research Clinical Trials in the European Union: Regulatory Legislative Framework A Canadian Perspective on Standard Operating Procedures Quality Management Systems: The Site How-to Guide to Creating a Sustainable Quality Management System (QMS) Electronic Data Capture in Clinical Trials: A Vendor View of the Risks, Challenges, and Benefits Moral Sensitivity in the SUPPORT Study SOCRA SOURCE © - November 2014 - 1 Quality Education Peer Recognition PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE ................................................ 4 SOCRA INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS ................................................ 5 CHAPTER PROGRAM Chapter Contacts .................................. 79-80 TABLE OF CONTENTS SELF-STUDY OPPORTUNITY FDA Guidance for Industry: Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Approval of Human Drugs and Biological Products - Part 1 ................................................ 7 Self Study Questions ........................................................................ 12 Self Study Answers ........................................................................... 39 PEER-REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLES Clinical Preparation and Defined Roles Increase Data Collection Quality and Result Integrity in Metastatic Thyroid Cancer Trials Madonna Pool, RN, BSN, MSN, CCRP .................................. 13 JOURNAL ARTICLES Project Management: Introduction to Tools and Templates Melissa Harris, CCRP ............................................................. 22 Preserving Integrity in Clinical Research: Avoiding Research Misconduct Lauren Solberg, JD, MTS ........................................................ 29 Effort and Complexity Tracking Metrics in Cancer Clinical Research Patricia Bebee, RN, BA, CCRP ............................................... 36 Clinical Trials in the European Union: Regulatory Legislative Framework Anatoly Gorkun, MD, PhD ....................................................... 40 A Canadian Perspective on Standard Operating Procedures Valerie Cronin, RN, SCM, BA (Hons), MA, CCRP .................. 44 Quality Management Systems: The Site How-to Guide to Creating a Sustainable Quality Management System (QMS) Christina R. Eberhart ............................................................... 55 Electronic Data Capture in Clinical Trials: A Vendor View of the Risks, Challenges, and Benefits Patricia M. Beers Block, BS, CCRP ........................................ 61 Moral Sensitivity in the SUPPORT Study Mark Hochhauser, PhD ........................................................... 68 IN MEMORIUM - Patrick T. Garoutte ........................................ 6 2014 ANNUAL CONFERENCE IN REVIEW .................... 51-54 CERTIFICATION .................................. 82 Eligibility ......................................................... 82 Examination Dates ........................................ 83 Application ..................................................... 84 24th ANNUAL CONFERENCE ............... 84 Registration ................................................... 85 Call for Poster Abstracts ................................. 86 Exhibitor Registration ................................... 87 Call for Speakers (2016 Conference) ........... 67 CONFERENCES AND SEMINARS Clinical Science Course ............................... 88 Social Media in Clinical Research ..................89 Clinical Research Monitoring Workshop ...... 90 Project / Program Management ................... 91 Human Research Protections/Legal Issues ...92 Clinical Investigator Workshop ...................... 93 Conducting Clinical Trials in Canada .......... 94 Certification Prep & Review Course ............ 95 Site Coordinator / Manager Workshop .......... 96 Advanced Site Management Finance and Productivity Workshop ................................. 97 FDA Clinical Trials Requirements .................. 98 SOP Workshop ........................................... 99 Pediatric Clinical Trials ............................... 100 Device Research and Regulations ..............101 ONLINE TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES cGMPs for INDs in Phase I Clinical Trials ...... 102 Steps Involved in FDA Inspections ........... 102 IND/ IDE Assistance ................................ 102 ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITIES Website Classified Advertising ........... 103 SOCRA Source Advertising ...................... 103 OPPORTUNITIES & SERVICES - INDEX University of Maryland ............................. 104 2013 Annual Conference Poster Abstracts - Begins on page 72 Clearer Nutritional Labeling May Improve Subject Compliance in Weight Loss and Satiety Trials The Clinical Trials Management Benefits of Implementing a Global Materials Protocol Implementation of Simple and Robust Systems to Provide ‘High Quality Trial Management’ Services for Phase I, II and III Clinical Trials Global Clinical Trials in Site Management in Japan from the Viewpoint of Clinical Research Coordinators SCTR Institute Research Coordination and Management Program Management of a Hospital-Integrated Biobank in the Baylor Health Care System Multicenter Clinical Trial Management Can a Central IRB Improve Efficiency and Human Subject Protection? Ambulatory Monitoring of Pulse Wave Velocity and its Application in Clinical Research Operational and Data Quality Considerations in the Transition of a Large Data Coordinating Center Clinical Trials in Emerging and Developing Countries by Taking the Example of India, Nigeria and South Africa A Systematic Review of the Literature on the Use of Placebo in Clinical Research Trials: An Ethical Dilemma SOCRA SOURCE © - November 2014 - 2 Electronic Data Capture in Clinical Trials: A Vendor View of the Risks, Challenges, and Benefits Patricia M. Beers Block, BS, CCRP Adjunct Assistant Professor Rutgers, The State University New Jersey Abstract: Electronic data capture (EDC) in clinical trials offers many benefits. However, there are also risks and challenges about which sponsors who choose and use EDC systems, and clinical research sites that use them must be aware.. This article describes the benefits, risks, and challenges of using EDC for clinical trials, from a technology provider’s perspective. The views and opinions expressed in the article are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Society of Clinical Research Associates or Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. Introduction to Vendor Applications Software vendors offer a full suite of applications that are useful in clinical research. Some offerings include: • applications that assist in the development of an electronic protocol; • the electronic review and signing of informed consent documents; • the collection of clinical data at the clinical site; • the assembly of data used to manage the clinical trial ; • applications that allow subjects to record study outcomes while participating in a clinical trial; • subject randomization procedures and results; • test article drug distribution applications; • the statistical analysis of data to assess the progress of the study; • Medical coding that standardizes information about medical procedures and adverse events; • the preparation of this data that meets standardized data formats for submission to regulatory authorities and other interested stakeholders; and • applications that capture pre-clinical data in electronic health records, data that can be integrated into clinical data applications. (Table 1). An application can be developed and offered as an independent application, in which case the application is capable of running independently and contains all of the modules needed to complete its expected actions. An example of an independent application is one that performs statistical analysis of clinical data. The data are uploaded via a prescribed format, and the data are processed by the application. No other interaction with another application is needed by the statistical program to complete the data analysis. Another program type commonly offered by software vendors are known as embedded programs. These programs are designed to perform a specific operation or set of operations within a larger application and/or system. An example of an embedded program is the calling (e.g., implementation) of a set of commands stored in a library file to perform desired operations. When the library file is called for use, the operations are performed and the data are preserved in a defined file. An embedded program typically does not exist as a SOCRA SOURCE © - November 2014 - 61 TABLE 1 EDC Offerings • Full suite of applications: oIntegrated EDC and EHR systems oPatient-reported outcomes (e-diaries) oStudy drug distribution and randomization (IXRS) oSubmission applications oStatistical applications (SAS) • Delivery approaches: oSoftware as a service (SAAS) (hosted) oTechnology transfer (non-hosted) separate application, but relies on the functionality of the hosting program. A final program type that is commonly developed by software vendors are integrated programs. With regard to how programs are offered to a client/customer, any of these applications can be delivered as software as a service (SAAS) applications (e.g., applications that are entirely hosted, and managed by a technology provider ) or through a technology transfer process (e.g., the application(s) would be completely installed on the customer’s hardware, and the customer would be responsible for the hosting and operation of the application). As an aside note, there is a move to offer applications as SAAS products, where a vendor provides access to a particular application via a subscription service. The length of time of an active subscription could be as short as the length of the clinical trial or as long as several years beyond the close of the trial if a sponsor or clinical research site wants the technology provider to retain and preserve its clinical data. With SAAS products, vendors typically upgrade an application and push the new version to the customer for its use. Customers may have a trial period during which they can test the new features of the upgrade, but customers usually have no choice in deciding whether to accept all of the new features; the new version is pushed out to all users and data are migrated to the new software version. Vendors are developing applications that can run on a variety of operating systems, browsers, and devices. It’s becoming more common to find EDC applications configured for a desktop computer, a laptop, a notebook, or a tablet device. Vendors also offer applications that can run on smart phones; and diagnostic devices. We can expect to see this trend continue where vendors develop applications for use on new technologies that make it easier to capture clinical data. Data Collection and Integration The EDC process starts with data input, which can be manual or automated. Laboratory information is often automated. A subject entering data into an e-diary or the study coordinator entering information into the EDC system are examples of manual data input. Then the data are processed, analyzed, and appropriately manipulated. The data may go through a transfer process, moving, for example, from the clinical research site to the SOCRA SOURCE © - November 2014 - 62 sponsor or to the technology provider. The output could be displayed on a monitor or presented in reports. The technology vendor can download the EDC application to a system or a device. Many E-PRO technology providers download the application to the device itself, although some e-diaries are now offered as Webbased systems and subjects are using iPads to collect data. The information flows through all of the interested parties: subject, institutional review board (IRB) or institutional ethics committee, investigator, study coordinator, sponsor, and laboratories. Ultimately, the data are handled in such a way that the sponsor does not have total control over them. The sponsor can never have data exclusively. A technology provider is an independent party that will preserve the data in a way that complies with regulatory requirements, especially those of the European Medicines Agency and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which are very concerned about one party having complete control over all of the data. Data integration refers to the data moving into the EDC system (Table 2). Vendors must be very flexible in the way they develop their applications because no one knows where the next system might come from or which data systems will be used to integrate data. EHR is today’s current challenge. Fortunately, organizations such as the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) have stepped in and are developing data standards. Through the Reference Forms Document, CDISC is helping to develop a process by which information from EHRs will be successfully integrated into EDC systems. The data that go into the system and go back to EHRs will TABLE 2 Data Integration • • • • • Flexibility and interest in total application integration Utilize data standards Need clear and complete system/application requirements Independence of data structure Understanding of and agreement on data retention only be those data that the sponsor or the subject wants returned to the EHR. The International Standards Organization is also working very hard to standardize not only the data format, but the way in which the data are collected. Utilizing data standards requires clinical research sites, sponsors, and IRBs to establish standards, which may be called edit checks. The standards would be things such as ranges of acceptable laboratory readings and broader organizational standards. CDISC’s C-Dash is an electronic representation of case report forms. CDISC is trying to determine how to successfully create an electronic case report form that will work across a number of different product lines in different therapeutic categories. important to not affect legacy data during migration. It is important to have a very clear understanding and agreement on the responsibilities of the sponsor and the technology provider. The sponsor must thoroughly consider the way in which all of the parties will communicate. The European Medicines Agency, in its Reflection Paper on eSource, underscored the need for a written contract between a technology provider and the sponsor. The sponsor must clearly understand what the technology provider will do and what it will provide to the sponsor and all of the other relevant parties. System and application requirements must be very clear. Thus, the sponsor must pay a great deal of attention to its requirements for conducting a study. Those requirements primarily come from the protocol. The regulatory agencies expect the protocol to identify which electronic systems will be used to capture data. The agreement must also address data retention and the archival processes. Some technology providers were offering unlimited archiving of data. As they grew, however, they realized that they could not continue to do this and began to look at ways to transfer the data back in a controlled fashion to the clinical research sites and the sponsors, only transferring the appropriate data to the sites. Therefore, it is important that organizations thoroughly consider what each party will contribute to the data retention and archival processes. The data structure must be somewhat independent. Migrating data is very challenging, as the new system will have additional parameters and it is Regulatory Expectations for EDC It is very important to consider regulatory expectations whenever considering the use of any type of electronic system. These expectations are outlined in the European Medicines Agency’s Reflection Paper on eSource and the FDA’s Guidance for Industry on Electronic Data Source used for Clinical Investigations. The first regulatory expectation is that the data be retained for the appropriate period of time. Both the FDA and the European Medicines Agency have stressed that checks and balances are still necessary with EDC, that is, clinical research sites must keep information about what they did during the conduct of the research. Sponsors must keep data that reflect what the investigators, laboratories, and any other parties involved, delivered in the EDC system. No one party can have exclusive control over all data. Neither the clinical investigator nor the sponsor can be the sole owner of all of the data. When selecting the EDC system, it is important to ensure that it can provide both parties with independent access to the data. The regulatory agencies expect the sponsor to have a contractual arrangement with the technology provider. The European Medicines Agency has stressed the need for a signed contract. The FDA has not explicitly stated this; however, it expects the sponsor to understand what the technology provider will be providing. It is always important to have this in writing. Another regulatory expectation is that the best practices from the paper process will be preserved in the electronic process. Thus, the data must still be attributable, legible, contemporaneous, original, and accurate. Benefits of EDC EDC offers many benefits to subjects, investigators, IRBs, and sponsors. SOCRA SOURCE © - November 2014 - 63 TABLE 3 Benefits of EDC • Benefits to subjects: oOnline and remote access training and help oElectronic reminders of data requirements oMore accurate recording of data: ▫▫ Units and terminology are integrated into the application oTechnology improvements have increased portability and ease of use • Benefits to investigators: oEnd-to-end applications are available oUse standardized data/fields oBuild edit check processes to improve data quality oRemote monitoring and data review oOnline and remote training and help access oConsistent look/feel by system users oPatient compliance and ease of use • Benefits to IRBs: oElectronic transfer and review of research proposals oConsistency among proposals oPotential for higher quality proposals oElectronic informed consent software applications and processes oElectronic tracking of reviews, requests for changes, and approvals/denials of research proposal • Benefits to sponsors: oImproved data quality and consistency oRapid access to data oRapid feedback to sites, contract research organizations, and clinical research associates oQuicker path to product approval (or decision to discontinue research) oElectronic submissions to regulators This technology can be cost effective in that it can speed up the process of collecting data and submitting them to regulatory authorities, thereby offering significant benefits to primarily investigators and sponsors. (Table 3) For subjects, EDC facilitates compliance, for example, with e-diaries. It is easy for subjects to use. Help is available if subjects have any problems, often on the device itself or in a manual that is easily accessible electronically or in a paper form. Through unique EDC features such as electronic alarms and reminders, subjects are reminded that data needs to be entered into ePRO devices, This SOCRA SOURCE © - November 2014 - 64 results in more accurate recording of data, which facilitates data integrity and data quality. Subjects can get immediate help from the electronic help modules that are embedded in most devices. Additionally, subjects who use electronic informed consent document applications can review the ICD and related educational material for as long as they like, and only electronically sign the ICD after all of their questions have been addressed by the software application, and the attending clinical staff. Sponsors, investigators and IRB members can be assured that the subject has a good understanding of the research into which the subject has volunteered. Behind the scenes, EDC systems capture metadata so that clinical research professionals know exactly when the subject completed the information. This eliminates the need for paper diaries. Thus, improved data can be sent to the regulatory authorities. Technology improvements occur continually, providing increased portability and ease of use. The benefits to the investigator include the availability of end-to-end applications. The EHR and EDC systems capture clinical data that the investigator can submit to the IRB. Many universities have developed electronic systems for the review of clinical trials. The investigator submits the protocol and all of the recruitment information into the electronic system and the IRB does the review electronically. This is a real benefit to the investigator, as he/she does not have to deliver reams of paper to the IRB’s office, ensure that it is distributed, and provide paper updates. EDC provides quick access to updated information. The investigator can create edit checks, using the sandbox environment that many technology providers offer. The sandbox is a weighted feature for user acceptance testing. A person enters data to determine whether the edit check works in an environment that is not live. EDC allows remote monitoring and data review with some types of electronic data capture. Commercial technology providers offer online and remote training and help. If the organization develops a system inhouse, it should definitely include these features. EDC also facilitates consistency and makes it easier for clinical research professionals to become comfortable using these systems. The IRBs at many universities have developed great EDC systems for review of clinical trials. As mentioned, these systems allow electronic transfer and review of research proposals. Commercial IRBs are also using EDC systems. Information in these EDC systems is easy to retrieve, update, and share among IRB members. EDC systems facilitate consistency among protocols, enabling IRB members to easily search for features that they expect to be part of a submission. EDC systems help IRBs comply with the rules that govern their operations and meet their regulatory requirements. They can also be used to capture informed consent and to track submissions. The benefits of EDC systems to the sponsor include improved data quality and consistency and rapid access to data at many levels. The biostatistician and the data management team can be looking at data while the clinical research sites are still collecting and inputting data. The monitor can review data electronically both remotely and onsite. EDC systems provide quick feedback to clinical research associates through the query approach, such as the need for an additional edit check or additional training. Sponsors can use EDC systems to make electronic submissions to regulators. TABLE 4 Challenges and Risks of EDC • • • • • • • • Global environment Technical, complex language translations Rapid changes in technology Rapid evolution of data storage practices Lack of, or evolving, data and submission standards Evolving regulatory policies and requirements More complicated security and business continuity plans Clear and understandable communications between all parties CDISC has developed a submission that the FDA has found acceptable, the standard data tabular approach module. Electronic submissions are also easier for the FDA to review than paper submissions. Challenges and Risks of EDC Table 4 outlines challenges and risks of EDC for vendors and, to some extent, for sponsors. The global environment requires dealing with different languages and having help available 24/7. Technology changes rapidly. Personal computers started with desktops, then moved to laptops. Floppy disks for storage were replaced by flash drives. Now storage systems are Web-based. Systems that were used on desktops or laptops are now used on Smartphones and other more modular devices. Electronic tablets are now being considered medical devices when data are collected on them and may, at some point, be regulated as medical devices. Sponsors that use EDC systems, as well as the vendors that make them, must keep up with the applicable regulations. Sponsors must purchase the right product to meet regulatory requirements. Data storage practices are evolving rapidly, and moving to the cloud. Sponsors that use technology providers that use cloud storage must ensure that they understand what this means. Cloud storage does not have all of the security features of Webbased systems, where the data are stored at the technology provider’s location on its own servers. With a cloud storage system, the data can be stored anywhere in the world, which is both good and bad. Sponsors must understand the standards that must be met in clinical research. For example, perhaps it is acceptable to have information about the application, such as the edit checks, stored in the cloud but the actual data should not be stored in the cloud. Data and submission standards may either be lacking or in an evolving state. CDISC and other standardsetting bodies are engaged in trying to set EDC standards. Technology providers are trying to keep up with this work. They, sponsors, and clinical research sites are actively engaged in discussions around building new standards. Any organization that is interested in EDC can be an active participant in all these activities. SOCRA SOURCE © - November 2014 - 65 Regulatory policies and requirements are evolving. Users finally have a good understanding of Part 11, Electronic Records; Electronic Signatures. The FDA is not changing its rules or orientation on Part 11. The FDA and the European Medicines Agency have provided some additional guidance on electronic source data, which has been very helpful. It is important for sponsors and technology providers to keep abreast of regulatory policies and requirements. Sponsors must ensure that the technology providers they use are aware of the latest policies and requirements. Security and business continuity plans are more complicated with EDC systems. The European Community expects data to be kept in the European countries unless there is a safe harbor agreement. Technology providers must be aware of security and data privacy issues and have procedures in place to deal with these issues. Clear and understandable communication between all parties is necessary, including who will be doing what, when, where, and why. For example, if a system changes, who will validate the revised system? If a technology provider is hosting all of the data, that technology provider must validate the system. If the system is being provided as a SAAS application, the technology provider may allow a clinical research site to use the application for a month or two before pushing it out. Real-Life Application of EDC Some interesting events related to EDC are occurring. New data requirements may necessitate software modifications and upgrades. The FDA has published a draft guidance on data standards, which recommends that if the standards change, EDC systems should be upgraded to push those standards. Other organizations recommend that this is not always necessary. There can be caveats as to when EDC systems need to be upgraded to new standards. For example, in a long-term, multisite study, it would be disruptive to change the EDC system every time there is a small change in standards. Clinical research sites would be using different standards at different times and integrating them at the end of the study could be a nightmare. In those cases, the sponsor should work with the FDA or other relevant regulatory authority to ensure that the regulatory authority understands that the sponsor will not be upgrading the EDC system and why. Data migration is a real challenge. Sponsors and clinical data management teams must thoroughly consider the requirements before employing an EDC system. It is especially important to consider anything that will be monitored because any changes to the system for monitoring will require data migration. The sponsor, clinical research sites, and technology providers will have to spend time to ensure that data migration works. Sometimes it does not. A great deal of time may be needed to check the data. The best remedy for this is better planning for implementation. Sponsors should test the EDC system and use the sandbox to test the edit checks and the parameters to ensure that they work. Anything that does not work should be changed before going into production. An implementation checklist is always helpful in tracking work. This should be a mindful checklist that contains the basics but grows and changes as the needs of a particular study change. One real-life event occurred when a sponsor supplied laptops to a clinical research site, collected the laptops at the end of the study, and left the site with no data from the study. In the past, the site would have paper data and records that were kept in the medical file or other records. In this case, the site had nothing to show its TABLE 5 Suggestions for Success in Using EDC Systems • Develop a detailed plan: oWho, what, when, where, and why • Document responsibilities and activities: oIn the contract and in the protocol • Assess vendors’ qualifications and applications • Communicate regularly: oAssess and mitigate risks oTrain and retrain as applications change • Stay tuned-in to regulatory discussions: oUse recommended data standards oUse recommended best practices oThink globally SOCRA SOURCE © - November 2014 - 66 work on the study. This is dangerous, not only for the sponsor, but also for the clinical investigator. If the sponsor had a problem with a server or the laptops crashed, there will be no evidence of the work done by that clinical investigator. Also, the expectation that clinical research data be independent has not been met. The remedy to this is to ensure that the contract covers data control and retention, and states that each party keeps its respective data in some format. In this case, a simple remedy would have been for the clinical research site to have copied the data from the study laptops onto one of its computers before the sponsor collected the laptops. The sponsor could also have sent the site a copy of the data, however, it is good practice to back up any system so the site should have had a back-up of the data, on, for example, a flash drive or on another hard drive. It may have been possible to print out the data. Another remedy is to create certified copies of the data, an exact copy that includes data and metadata, on a flash drive, and retain this throughout the study. Suggestions for Successful Use of EDC Systems Table 5 outlines suggestions for successful use of EDC systems, including developing a detailed plan that covers who, what, when, where, and why. The plan should include which parties will be contributing data, how they will be doing this, how often the data will be put into the system, and whether the system will be used to collect e-source. It is acceptable from a regulatory perspective for a clinical research site to put data into an EDC system and never record it on paper. However, if this is how the study will be operated, this should be clearly noted in the plan. The roles and responsibilities related to EDC should be documented in the contract and the protocol. Vendors’ qualifications and applications should be assessed. Vendors might present a sophisticated system with all of the bells and whistles. However, all of those bells and whistles may not be needed. It is necessary to know that the vendor is qualified and reliable, and that it validates its application and offers training and help. The vendor should also have a process for developing software and the application must be reliable and trustworthy. Staying tuned to regulatory discussions is also important. Data standards should be used, including those of CDISC and other standardsetting bodies. Global thinking is required. While many regulatory authorities have harmonized their regulations with the International Conference on Harmonization E6 Good Clinical Practice, not all countries do this. It is also important to meet local regulatory requirements. 25th Annual Conference CALL FOR SPEAKERS September 30 to October 2, 2016 Montréal, QC Canada Please consider contributing to this very important meeting through your participation in the speaker program. There are a number of areas pertinent to clinical research professionals that will be emphasized during our conference. • Site Management - Informed Consent, Enrollment Process, Finance & Budgeting, GCP • Your therapeutic area in research (i.e.: radiation therapy, etc.) • Subject Enrollment and Follow-up • Project / Program Management • Data Technology and Collection • Patient Compliance / Issues of Drug Interactions (patients on multiple studies) / AE & SAE Reporting • IRB/EC Guidelines, Informed Consent, & Records Management • Auditing / Monitoring / Documenting • Drugs / Devices / Biologics • Quality Assurance - GCP / ICH / NIH - Guidelines and Regulations SOCRA encourages responses to this call for papers from persons working at investigational sites and persons working for SMOs, sponsor companies, CROs, and government; from those working for providers of technology solutions, and other service providers. Presentations, however, must not promote specific products or services. All speakers receive a fee-waived registration to the (main) conference. Guidelines for submissions & other information may be found at www.socra.org/annual-conference SOCRA SOURCE © - November 2014 - 67