CSC TXT-VOL01-Chap05 2013 01 EN V01

advertisement

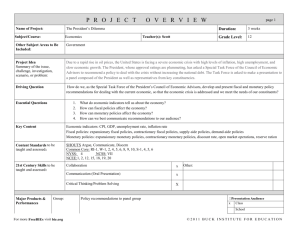

Chapter 5 Economic Policy © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•1 5 Economic Policy CHAPTER OUTLINE What are the Different Economic Theories? • Rational Expectations Theory • Keynesian Theory • Monetarist Theory • Supply-Side Economics What is Fiscal Policy? • The Federal Budget • How Fiscal Policy Affects the Economy What is the Role of the Bank of Canada? • Role of the Bank of Canada • Functions of the Bank of Canada What is Monetary Policy? • Implementing Monetary Policy • Open Market Operations • Cash Management Operations What are the Challenges of Government Policy? • The Consequences of Failed Fiscal Policy Summary 5• 2 © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end of this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Compare and contrast the rational, Keynesian, monetarist and supply-side theories of the economy. 2. Analyze the mechanisms by which governments establish fiscal policy and evaluate the impacts of fiscal policy on the economy. 3. Explain the role and functions of the Bank of Canada. 4. Analyze how the Bank of Canada implements and conducts monetary policy. 5. Discuss the challenges governments face in their fiscal and monetary policies and the consequences of failed policy. ROLE OF ECONOMIC THEORIES In February each year, the Federal Minister of Finance announces the government’s budgetary requirements, which is its annual fiscal policy score card of spending and taxation measures. Not far from Parliament Hill, the Bank of Canada watches over the economy and uses monetary policy and its influence over interest rates and the exchange rate to maintain balance. Although the government and the Bank operate mostly independently of one another, both have a goal of creating conditions for long-term, sustained economic growth. This chapter builds on information in the previous chapter about the principles of economics to explore the benefits and costs of fiscal and monetary policy, particularly from the standpoint of making investment decisions. For example, if you believe the economy is moving through expansion into the peak phase of the business cycle, what investments or strategies would you pursue given the policy action the Bank of Canada is likely considering? If the economy has been stalled in recession and unemployment continues to rise, what fiscal policy options is the federal government likely to consider? Understanding what route economic policy will follow is a factor in making investment decisions. It is important, therefore, to be familiar with the fiscal and monetary policy options available to the government and how these policy actions will affect financial markets. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•3 KEY TERMS Bank rate Monetarist theory Basis points Monetary policy Budget deficit National debt Budget surplus Overnight rate Canadian Payments Association (CPA) Rational expectations theory Drawdown Redeposit Fiscal agent Sale and Repurchase Agreements (SRAs) Fiscal policy Special Purchase and Resale Agreements (SPRAs) Keynesian economics Supply-side economics Large Value Transfer System (LVTS) 5•4 © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) FIVE • ECONOMIC POLICY 5• 5 WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENT ECONOMIC THEORIES? Prior to the 1930s, most economists believed that the market followed a self-correcting mechanism and would automatically adjust to temporary imbalances. Left to these built-in stabilizers, market adjustments would quickly move the economy from recession to a stable growth path. Over the years, a number of theories have been put forward to help us better understand the workings of the economy. Rational Expectations Theory Rational expectations theory suggests that firms and workers are rational thinkers and can evaluate all the consequences of a government policy decision, thereby neutralizing the intended impact of the policy. Example: Suppose the government decides to cut taxes temporarily in order to boost consumer spending and improve economic conditions. If consumers behave rationally, they will realize that the tax cut will create a deficit that eventually has to be repaid with higher taxes. Instead of spending the tax cut, they save it to repay future taxes, and the government’s move has no impact. Keynesian Theory Keynesian economics advocates the use of direct government intervention as a means of achieving economic growth and stability. British Economist John Maynard Keynes offered an alternative to the view that the economy worked best when left to its own devices. Example: Consider the case when the economy enters a recession. Keynesians advocate an increase in government spending or lower taxes to raise consumer income. With more money in their pockets, consumers increase their spending on goods and services. To meet the higher consumer demand for their products, businesses hire more workers to expand production and unemployment falls. Lower unemployment leads to a further increase in consumer income and spending. The increase in income and spending may continue for some time. However, once policymakers believe that spending is rising too quickly, policy will change to reflect lower government spending and higher taxes. The analysis Keynes put forward became the rationale for the use of government spending and taxation to stabilize the business cycle. When spending was insufficient and a recession loomed, government would pursue a policy of increased spending and lower taxes. During an economic boom and when higher spending threatened inflation, government policy would change in favour of lower spending and higher taxes. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5• 6 CANADIAN SECURITIES COURSE • VOLUME 1 Monetarist Theory Monetarist theory suggests that the economy is inherently stable and, left to its own selfadjusting mechanism, will automatically move to a stable path of growth. In contrast to the Keynesian view, the Monetarist movement, led by American economist Milton Friedman in the late 1950s, held that instability in the money supply is the major cause of fluctuations in real GDP and that rapid money supply growth is the major cause of inflation. In fact, it was Friedman who coined the phrase “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Example: Monetarists believe that instead of pursuing active monetary or fiscal policy, the central bank should simply expand the money supply at a rate equal to the economy’s long-run growth rate – somewhere in the neighbourhood of 2% to 3% per year, for example. According to this view, controlling inflation as the main policy goal creates a foundation for the economy to grow at its optimal rate. Supply-Side Economics According to supply-side economics, to foster an environment of prosperity, the market should be left on its own and government intervention should be held to a minimum. Although there are similarities with the monetarist view, “supply-siders” suggest that government intervention should only occur through changes in tax rates. Example: Specifically, this view advocates that changes in tax rates exert important effects over supply and spending decisions in the economy. They maintain that reducing both government spending and taxes provides the stimulus for economic expansion. Reducing taxes and the size of the government would help to fuel economic expansion. According to supply-siders, a reduction in marginal tax rates stimulates investment in the economy and ultimately leads to a higher level of output. Complete the following Online Learning Activity Economic Theories In this activity, you will review the various economic theories that have been put forward to help us better understand the workings of the economy. Complete the Economic Theories activity to review each of the economic theories that drive current policy. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) FIVE • ECONOMIC POLICY 5•7 WHAT IS FISCAL POLICY? Governments, through their power to tax, spend, and borrow, exercise enormous influence on the economy. Since the end of the Second World War, most Western governments have taken it for granted that one of their mandates is to smooth out the fluctuations in the business cycle. Fiscal policy is the use of the government’s spending and taxation powers to pursue such economic goals as full employment and sustained long-term growth. They do this by spending more and taxing less when the economy is weak, and by spending less and taxing more when the economy is strong. Both the federal and provincial governments play a role in Canadian fiscal policy. Both have responsibility for certain areas of activity. The federal government is responsible for such things as employment insurance, defence, old age security, veterans’ affairs and native affairs. The provincial governments are responsible for health, education and welfare. However, the federal government shares some responsibility for those areas with the provinces. A large segment of its spending consists of transfer payments to the provincial governments to pay for health, education and welfare. At times, federal deficit reduction efforts result in cuts to these transfers, putting upward pressure on provincial deficits, since the provinces have little other revenue to compensate for the loss of transfers. Federal and provincial governments oversee important areas of spending that do not appear on their respective budgets. These include the Canada and Quebec Pension Plans, Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, the Export Development Corp., and a wide range of other crown corporations ranging from Canada Post to Quebec’s Société générale de financement. In theory, most of these agencies are meant to be self-supporting. In practice, many accumulate large deficits or unfunded liabilities, which are the responsibility of the government that runs the agency or corporation. The Federal Budget Early each year, usually in February, the federal Minister of Finance presents to the House of Commons the federal budget for the upcoming fiscal year, which runs from April 1 to March 31. The budget contains projections for the coming year, and usually for at least one subsequent year, for spending, revenue, the amount of the projected surplus or deficit, and debt. An important part of the budget is the economic assumptions that underlie projections for tax revenue, debt service costs and other parts of the budget. The government’s budget balance is equal to its revenues less its total spending. • If the revenue collected during the year exceeds spending for the year, the government has a budget surplus. • If total spending for the year is higher than the revenue collected, the government has a budget deficit for the year. • Accordingly, if the revenue collected for the year equals total spending, the government has a balanced budget. When the government runs a budget deficit, it must borrow to make up the difference by selling government bonds and Treasury bills into the market. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5• 8 CANADIAN SECURITIES COURSE • VOLUME 1 • The accumulation of total government borrowing over time is referred to as the government debt or the national debt. It is the sum of past deficits minus the sum of past surpluses. The amount of the surplus or deficit is the most important number in the budget, because it tells markets the extent to which the government will be borrowing in the coming year and how it will compete with other borrowers for funds. If the government predicts a deficit, the amount projected in the budget may differ from what the government actually borrows in the debt market (called its financial requirements) for several reasons: • Previously issued bonds that mature in the coming fiscal year must be refinanced. Since this is not new borrowing, it is usually not included in projected financial requirements. • The government has access to several special-purpose accounts for funds. These alternatives reduce its dependence on debt markets. The most important source of such funds is the civil service pension fund. This is the main reason financial requirements are usually less than the deficit. How Fiscal Policy Affects the Economy Fiscal policy affects the economy in several ways: • Spending: Governments can purchase goods or services themselves, such as a new highway, thereby boosting economic activity. Or they can simply transfer money to citizens to spend or save themselves, such as with social security cheques. Only the first type is recorded as government spending in GDP. • Taxes: The amount of tax collected may vary because the size of the tax base changed, i.e., the number of people or companies paying the tax expanded or contracted. Also, it can vary because the tax rate changed, so that each dollar of economic activity yields more or less tax. Raising tax rates reduces the disposable income of consumers, thereby dampening their spending. The main types of taxes are: – Direct taxes, levied on the income of individuals and companies; – Sales taxes (including value-added taxes, like the goods and services tax, and excise taxes, such as on liquor); – Payroll taxes, levied as a share of wages; – Capital taxes, levied on the size of a company’s assets or capital; – Property taxes, levied on residential and commercial property. All taxes tend to discourage the type of activity being taxed. Income taxes reduce the incentive to work and earn; payroll taxes reduce the incentive to hire; and sales taxes reduce the incentive to spend. Persistent deficits emerged during the 1980s and the annual deficit grew considerably. Unfortunately, a vicious circle emerged: the deficit led to increased borrowing; this led to a larger national debt and larger interest payments to service the debt; and these larger interest payments led to a larger deficit and a larger debt. In fact, it was not until 1997 that the federal government finally managed to run a surplus. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5• 9 FIVE • ECONOMIC POLICY EXHIBIT 5.1 FEDERAL GOVERNMENT DEBT AS A PERCENTAGE OF GDP From its dollar peak of $563 billion in 1996–1997, the federal debt has declined by $100 billion to $463 billion as of March 31, 2009. This is good news from a global perspective, as Canada’s federal debt as a percentage of GDP fell significantly over the past decade. The debt-to-GDP ratio is regarded as a sound measure of a nation’s overall debt burden because it measures the debt relative to the ability of the government and the nation’s taxpayers to finance it. The figure shows the federal government debt as a percentage of GDP for Canada from 1975 to the end of the 2008-2009 fiscal year. 80 70 Debt-to-GDP (%) 60 50 40 30 20 10 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Year Source: Annual Financial Report of the Government of Canada, Fiscal Year 2008-2009. As a share of GDP, federal debt dropped to 32.8 % in 2008-2009, down from its peak of 68.4% in 1995–1996. The debt-to-GDP ratio has steadily declined over the last 15 years, and is now back to the levels of early 1980s. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•10 CANADIAN SECURITIES COURSE • VOLUME 1 Complete the following Online Learning Activity Fiscal Policy Macroeconomic policies fall into two categories: monetary policy and fiscal policy. Monetary policy uses interest rates, exchange rates and the money supply to influence consumer demand and control inflation. Fiscal policy tries to regulate growth through government taxation and spending. In this activity on fiscal policy, you will review the policy-making process and who makes the decisions, and learn more about how fiscal policy affects the economy. Review Fiscal Policy with this activity. WHAT IS THE ROLE OF THE BANK OF CANADA? The Bank of Canada (the Bank) was founded in 1934 and began operations in 1935 as a privately owned corporation. By 1938, ownership passed to the Government of Canada. Responsibility for the affairs of the Bank of Canada rests with a Board of Directors composed of the Governor, the Senior Deputy Governor and twelve Directors from outside the Bank. Role of the Bank of Canada The duties and role of the Bank are stated in a general way in the preamble of the Bank of Canada Act: • “To regulate credit and currency in the best interests of the economic life of the nation... • To control and protect the external value of the national monetary unit... • To mitigate by its influence fluctuations in the general level of production, trade, prices and employment, as far as may be possible within the scope of monetary action and generally... • To promote the economic and financial welfare of the Dominion.” The Act does not specify the manner in which the Bank should pursue these objectives but it (and other legislation) grants powers to the Bank which are designed to enable it to fulfill its role. While the Bank administers policy independently without day-to-day Government intervention, the thrust of policy is the ultimate responsibility of the elected Government. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) FIVE • ECONOMIC POLICY 5•11 Functions of the Bank of Canada The major functions of the Bank of Canada are: • To act for the Government in the issuance and removal of bank notes; • To act as the Government’s fiscal agent (i.e., being the Government’s financial advisor on debt management, foreign exchange and monetary policy and acting as its agent in financial transactions); and • To conduct monetary policy (i.e., managing the supply of the nation’s money). This is the Bank’s most important function. As fiscal agent to the Government, the Bank has a variety of functions. The Bank administers the Government’s deposit accounts and funds. This includes: • Deposit accounts with the Bank of Canada and the chartered banks in which Government cash is held; and • The Exchange Fund Account, which holds the Government’s foreign exchange reserves. Almost all of the Government’s Canadian dollar receipts and expenditures flow through the account it maintains at the Bank of Canada. The Bank manages Canada’s official international currency reserves. It operates for the Government in foreign exchange markets in keeping with its mandate “to control and protect the external value of the national monetary unit.” The Bank of Canada Act empowers the Bank to: • Buy and sell gold, silver and foreign exchange; • Maintain deposits with other central banks and commercial banks inside and outside Canada; and • Act as agent and depository for central banks and certain international institutions. As is the case in connection with monetary policy and debt management, the Bank provides the Government with information and advice and acts as its agent in dealings in gold and foreign exchange. The Bank acts as a depository for gold held by the Exchange Fund Account. It also buys and sells gold. This activity has diminished importance reflecting the marginal role of gold in securing the value of the Canadian dollar. Financial advisor to the Government: The Bank advises the Government on the timing of new federal securities issues. It advises on the price, yield and other special features needed to make them marketable. The Bank also advises the Government about where such securities should be sold (i.e., domestically, in the U.S. or offshore). In order to keep abreast of market developments, the Bank conducts regular discussions with investment dealers, bankers and other investors to obtain views and suggestions. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•12 CANADIAN SECURITIES COURSE • VOLUME 1 Debt management: The Bank of Canada acts as the federal Government’s fiscal agent in its activities in debt management. The planning and arrangements necessary for a new debt issue are major undertakings. Not only must each issue be distributed and sold, arrangements for payments, transfers of funds, etc., must be made. Then there is regular record keeping, payments of interest, transfers of ownership and finally providing funds to repay the issue at maturity. The Minister of Finance is responsible for debt management programs but relies on the Bank for advice and implementation of policy. While there is a wide range of maturities in Government debt, there are two principal categories of debt: marketable (treasury bills and marketable bonds) and non-marketable (Canada Savings Bonds and Canada RRSP Bonds). These securities are discussed in the material on fixed-income products. Complete the following Online Learning Activity Bank of Canada The Bank of Canada plays a key role in the Canadian economy since its mandate includes: • Regulation of credit and currency; • Control and protection of the external value of the Canadian dollar; • Maintenance of stability in the market; and • Promotion of the economic and financial welfare of Canada. Learn more about the Bank’s role and its function in the Canadian economy in the Bank of Canada activity. WHAT IS MONETARY POLICY? Monetary policy sets out to improve the performance of the economy by regulating the growth in money supply and credit. The goal of monetary policy is to ensure that money can play its vital role in helping the economy run smoothly. Canadian monetary policy strives to protect the value of the Canadian dollar by keeping inflation low and stable. As Canada’s central bank, the Bank of Canada achieves this through its influence over short-term interest rates. The goal of monetary policy is to preserve the value of money by promoting sustained economic growth with price stability. In other words, growth in levels of employment, consumption and our standard of living generally should be supported by increasing liquidity in the system at a rate that is not inflationary. Over time, inflationary increases erode the value of our currency and ultimately our economic health. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) FIVE • ECONOMIC POLICY 5•13 Since 1991, the Bank has committed to specific inflation-control targets that establish a target range within which it aims to contain annual inflation as measured by the year-over-year rate of increase in the CPI. Currently, the target range extends from 1% to 3%. Here is how the Bank keeps inflation within this range: • If inflation approaches the top of the target range, this usually indicates that the demand for goods and services is rising too strongly and must be controlled through an increase in shortterm interest rates. • If inflation falls towards the bottom of the target range, this usually indicates that economic growth is slowing or weakening and support is needed through a decrease in interest rates. Over the long run, the rate of inflation is linked to the rate of growth of money and credit. Through its influence over short-term interest rates, the Bank affects the demand for, and supply of, money and credit. The influence of monetary policy on total spending is exerted indirectly and with some time lag – roughly one to two years. Monetary policy must therefore be forward looking. Thus, the Bank conducts monetary policy by consistently aiming their efforts at the midpoint of the target range. That is, by aiming for an inflation rate of 2% over the next 12-month period, the Bank believes it can achieve its inflation-control targets. Implementing Monetary Policy The Bank of Canada carries out monetary policy primarily through changes to what it calls the Target for the Overnight Rate. The overnight rate is the interest rate set in the overnight market – a marketplace where major Canadian financial institutions lend each other money on an overnight basis. When the Bank changes the target for the overnight rate, other short-term interest rates also usually change. Currently, the overnight rate operates within a 50 basis points (or one-half of a percentage point) wide operating band. Each day, the Bank targets the mid-point of the operating band as its key monetary policy objective. For example, if the operating band is 5% to 5.5%, then the target for the overnight rate is 5.25%. The target is an important policy tool as it may signal a policy shift towards an easing or tightening of monetary conditions in order to meet the Bank’s inflation-control targets. The Bank Rate is the minimum rate at which the Bank of Canada will lend money on a short-term basis to the chartered banks and other members of the Canadian Payments Association (CPA) in its role as lender of last resort. It is closely related to the Target for the Overnight Rate because the Bank Rate is the upper limit of the operating band. Continuing with our example from above, with an operating target range of between 5% and 5.5%, the Bank Rate is 5.5%. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•14 CANADIAN SECURITIES COURSE • VOLUME 1 Figure 5.1 illustrates a hypothetical example of the target range for the overnight rate. FIGURE 5.1 EXAMPLE OF THE BANK OF CANADA’S OPERATING BAND 5.5% 5.25% Bank Rate 50 basis points target range 5.0% Bank Rate less 50 basis points Standing arrangements are in place under which the Bank is prepared to provide secured loans (at the Bank Rate) for one business day to the chartered banks and members of the CPA. Such access to central bank credit plays a useful role in providing individual banks and dealers with a safety valve. Such access provides an underlying assurance of liquidity in circumstances when funds are not readily available from other sources. The Bank is accordingly known as the banking system’s lender of last resort. Open Market Operations The two main open market operations that the Bank uses to conduct monetary policy are Special Purchase and Resale Agreements and Sale and Repurchase Agreements. Special Purchase and Resale Agreements (commonly referred to as SPRAs or “Specials”) are used by the Bank of Canada to relieve undesired upward pressure on overnight financing rates. If overnight money is trading above the target of the operating band, the Bank may believe that the higher rate will dampen economic activity. To combat this, the Bank intervenes and offers to lend at the upper limit of the operating band. For example, if the upper limit of the operating band is 4.25% while overnight money trades at 4.50%, it does not make sense for financial institutions to borrow at the higher overnight rate. SPRAs work as follows: • The Bank offers to purchase government securities from a primary dealer (such as a chartered bank) with an agreement to sell them back the next day at a predetermined price. • When the Bank purchases securities from an institution, they pay the institution cash for the securities. Essentially, the cash payment acts as a very short-term loan. • The next day, when the securities are resold to the institution, the Bank receives money in exchange for the securities they are returning. This operation is used to reinforce the upper limit or top end of the overnight target and is closely watched by market participants. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•15 FIVE • ECONOMIC POLICY Sale and Repurchase Agreements (SRAs) are used to offset undesired downward pressure on overnight financing costs. If overnight money is trading below the target of the operating band, the Bank may believe that inflationary pressures in the economy will rise. To combat this, the Bank intervenes and offers to borrow at the lower limit of the operating band. For this example, if the lower limit of the operating band is 3.75% while overnight money trades at 3.50%, financial institutions would much prefer the Bank of Canada rate. SRAs work as follows: • The Bank offers to sell government securities to chartered banks with an agreement to repurchase them the next day at a predetermined price. • In exchange for the sale, the Bank receives money. Essentially, the Bank is borrowing money from the Chartered Bank when it sells securities under this program. • The next day, the Bank repurchases those securities in exchange for the cash. In effect, the money they borrowed is paid back. This operation is used to reinforce lower the limit or floor of the operating band and is the focus of considerable market attention. On a number of occasions, the offering itself is sufficient to eliminate the downward pressure on the overnight rate. Partly as a result of this, the amounts of SRAs dealt tend to be quite small relative to SPRAs. Figure 5.2 shows that SPRAs are conducted at the top end of the band, which is also the Bank Rate, while SRAs are conducted at the bottom end of the band. FIGURE 5.2 THE OPERATING BAND SPRA – the Bank lends overnight at the upper limit of the operating band Bank Rate Operating Band = 50 basis points wide Bank Rate less 0.50% SRA – the Bank sells securities at the lower end of the operating band Instead of letting it vary from day to day depending on conditions in the market, the Bank aims to keep the overnight rate within its 50-basis-point range. Financial institutions know that the Bank will always lend money at the upper end of the band, and borrow money at the lower limit of the band. Thus it makes no sense to trade in the overnight market at rates outside this band. It repeatedly conducts similar operations to keep most of the overnight trading within the range. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•16 CANADIAN SECURITIES COURSE • VOLUME 1 If the Bank is changing the range, it enters the market and conducts specials or SRAs at the new ceiling or floor. Alternatively, the Bank allows the overnight rate to move to its new range, then confirms the new target with open market operations. Changes in the overnight band (and therefore, the Bank Rate) are now accompanied by a press release explaining the Bank’s actions. The Bank’s intention is to make such changes as transparent (or clear) as possible to avoid confusion in financial markets. Cash Management Operations The trend of the Bank Rate is important to both users and suppliers of credit. A rising trend, for example, signals a desire on the part of the Bank to reduce the demand for credit by raising its cost. Administered rates such as prime rates (i.e., chartered bank rates to their prime or most creditworthy borrowers) usually follow the trend of the Bank Rate. EXHIBIT 5.2 THE LARGE VALUE TRANSFER SYSTEM Each day, billions of dollars flow through the financial system to settle transactions between the major financial institutions. These transactions include cheques, wire transfers, direct deposits, preauthorized debits and bill payments. To facilitate the transfer of these payments, the Bank established the Large Value Transfer System (LVTS) in 1991. This system allows participating financial institutions to conduct large transactions with each other through an electronic wire system. Among other things, this system permits these financial institutions to track their LVTS receipts and payments electronically throughout the day and to know the net outcome of these flows by the end of the day (same day settlement). How the LVTS works This system provides an important setting for conducting monetary policy. Throughout the day, financial institutions in the LVTS send payments back and forth to each other as part of their normal operations. At the end of each day, all of the transactions that occurred during the day are added up, and some financial institutions may end up needing to borrow funds while some may have funds left over. Example: Bank A had $50 million in payments to other financial institutions and $40 million in receipts during the day. At the end of the day, it finds itself in a deficit position of $10 million for that day. Since participants in the LVTS are required to clear their balances with one another each day, Bank A will need to borrow $10 million in funds to cover that position. Bank A will then need to borrow the funds from another participant in the LVTS at the current overnight rate. Overall, the LVTS helps to ensure that trading in the overnight market stays within the Bank’s 50basis-point operating target. LVTS participants know that the Bank will always lend money at the upper limit of the band, and will borrow money at the lower limit of the band. Therefore, it does not make sense for financial institutions in the LVTS to borrow or lend outside of the target band. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•17 FIVE • ECONOMIC POLICY DRAWDOWNS AND REDEPOSITS The federal government maintains accounts with the Bank of Canada and the chartered banks. As the banker for the federal government, the Bank of Canada can transfer funds from the government’s account at the Bank to its account at the chartered banks or from the government’s account at the chartered banks to its account at the Bank of Canada. This strategy is used to influence short-term interest rates and is achieved using drawdowns or redeposits. • A drawdown refers to the transfer of deposits to the Bank from the chartered banks, effectively draining the supply of available cash balances from the banking system. This decreases deposits and reserves available to the banks to utilize in their business. Removing money from the system causes a contraction in the availability of loans to consumers and businesses, and this places upward pressure on interest rates. • A redeposit is just the opposite, a transfer of funds from the Bank to the chartered banks. This increases deposits and reserves and the availability of funds in the banking system. Adding money to the system places downward pressure on interest and gives banks an incentive to increase loans to consumers and businesses. Complete the following Online Learning Activity Monetary Policy The Bank of Canada’s key function is to set monetary policy, which means it manages the supply of money in the economy. The Bank needs to ensure that growth in levels of employment and consumption, and in Canadians’ standard of living, is generally supported by increasing liquidity in the system at a rate that is not inflationary. Complete the Monetary Policy exercise to review how the Bank of Canada implements monetary policy. WHAT ARE THE CHALLENGES OF GOVERNMENT POLICY? Disagreements about the role and nature of government policy are often related to basic differences in analyzing how the economy reacts to changing circumstances. Two attitudes are widespread. The first emphasizes that the economy may be slow to react. As a consequence, interventionist policy may not be effective or even essential in guiding the economy in the right direction. The alternative view emphasizes that the economy makes its way quickly to its natural equilibrium, and that no need exists for policy other than to constrain policy. This difference, for example, is at the heart of the controversy surrounding the role of money growth. Monetary policy may be seen to be effective in the short run but not in the long run. What is unknown is how long is the short run. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•18 CANADIAN SECURITIES COURSE • VOLUME 1 Two sections in Chapter 4 dealt with the evolution of the economy in this framework. The discussion of the short run emphasized the business cycle and the problems posed by downturns in the cycle. The second dealt with the determinants of long-run growth and emphasized the role of technological development in supporting continued gains in productivity. Government policy in the first context is directed towards counter-cyclical initiatives, and in the second context to the development of human capital and the enhancement of technological advances. In recent years, the federal government has dealt successfully with reducing the deficit to the extent that there is some fiscal room to manoeuvre. Ultimately, the policy challenge for the government is to evaluate the competing claims of those who stress the need for intervention and flexible stabilization policies versus those with a more restrictive view of the role of government in guiding the economy. Each choice has both growth and uncertainty implications for the overall Canadian economy, and for the financial investments issued by both governments and corporations. The Consequences of Failed Fiscal Policy In the past, governments’ failure to address their budget deficits have had several consequences: • Because governments did not eliminate the deficit when it first emerged seriously in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the cost of interest payments on the national debt began to rise rapidly and remained high through the early 1990s. They were the federal government’s single biggest expenditure throughout most of the 1990s, peaking at 27.1% of total spending in 1998–1999, compared to 10.3% in 1974–1975. In turn, the interest burden made it difficult for the government to reduce the deficit. It did so by drastically cutting total expenditures, especially transfer payments to the provinces. Successive budget surpluses in the 2000s helped to lower the federal government’s overall debt position, with the cost of interest payments falling to about 13% of total expenditures in the government’s 2008-2009 fiscal year. • Fiscal policy is often unsynchronized with monetary policy, increasing the cost to the economy. For example, in the late 1980s when the economy was growing strongly and inflationary pressure was building, federal and provincial governments in Canada continued to run large deficits. This tended to increase inflationary pressures and led the Bank of Canada to raise interest rates more than would otherwise have been necessary. In turn, the cost of servicing government debts grew and contributed to increased deficits. • In the end, a large national debt constrains the ability of governments to run countercyclical fiscal policy. When debts are large, any move to increase the deficit upsets investors, who sell bonds, driving up interest rates. This reaction reduces the beneficial impact on the economy of the increased deficit. When a recession occurs, the government may cut spending and raise taxes to control its growth and, as a consequence, worsen the recession. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) FIVE • ECONOMIC POLICY 5•19 SUMMARY After reading this chapter, you should be able to: 1. 2. Compare and contrast the rational, Keynesian, monetarist and supply-side theories of the economy. • The rational expectations theory suggests that firms and workers are rational thinkers and can evaluate all the consequences of a government policy decision, thereby neutralizing its intended impact. • Keynesian economics advocates the use of direct government intervention to achieve economic growth and stability. Keynesians believe the use of active fiscal policy, using government spending and taxation, is necessary to stabilize the business cycle. • Monetarist theory suggests that the economy is inherently stable, with its own selfadjusting mechanism that automatically moves the economy to a stable path of growth. Monetarists argue against the use of active monetary or fiscal policy and believe the central bank should simply expand the money supply at a rate equal to the economy’s long-term growth rate. • Supply-side economics suggests that to foster an environment of prosperity, the market should be left alone and government intervention should be minimal, only occurring through changes in tax rates. This theory maintains that lower government spending and lower taxes provide the stimulus for economic expansion. Analyze the mechanisms by which governments establish fiscal policy and evaluate the impacts of fiscal policy on the economy. • Fiscal policy is the use of government spending and taxation to pursue full employment and sustained long-term growth. In general, governments pursue this goal by spending more and taxing less when the economy is weak, and by spending less and taxing more when the economy is strong. • In Canada, the federal budget is the key mechanism through which the government conducts fiscal policy. The budget contains projections for the coming year for spending, revenue, and the amount of the projected surplus or deficit. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•20 CANADIAN SECURITIES COURSE • VOLUME 1 3. 4. Explain the role and functions of the Bank of Canada. • The role of the Bank of Canada is to monitor, regulate and control short-term interest rates and the external value of the Canadian dollar. • The major functions of the Bank of Canada include the issue and removal of bank notes, acting as fiscal agent and financial advisor for the Federal Government, and the implementation of monetary policy. • The goal of monetary policy is to improve the performance of the economy by regulating growth in the money supply and credit. The Bank of Canada achieves this through its influence over short-term interest rates. Analyze how the Bank of Canada implements and conducts monetary policy. • In Canada, monetary policy involves following specific inflation-control targets that establish a range within which to contain annual inflation. Currently, the target range is 1% to 3%. • The Bank uses the target for the overnight rate to implement changes in the direction of monetary policy. The overnight rate is the interest rate set in the overnight market. When the Bank changes the target for the overnight rate, other short-term interest rates also tend to change. • Special Purchase and Resale Agreements (SPRAs) and Sale and Repurchase Agreements (SRAs) are the two main open market operations used by the Bank to conduct monetary policy. – SPRAs are used to relieve undesired upward pressure on the overnight rate. If overnight money trades above the target of the operating band, the Bank intervenes and offers to lend at the upper limit of the band. This action effectively reinforces the upper limit of the overnight target. – SRAs are used to offset undesired downward pressure on the overnight rate. If overnight money is trading below the target of the operating band, the Bank intervenes and offers to borrow at the lower limit of the band. This action effectively reinforces the lower limit of the overnight target. • The Bank established the Large Value Transfer System (LVTS) in 1991 to facilitate its cash management operations. This system allows participating financial institutions to conduct large transactions with each other through an electronic wire system. This system provides an important setting to conduct monetary policy. • A drawdown is the transfer of deposits to the Bank from the chartered banks, effectively draining the supply of available cash balances from the banking system. This causes a contraction in the availability of loans to consumers and businesses, which places upward pressure on interest rates. • A redeposit is the transfer of funds from the Bank to the chartered banks, effectively increasing deposits and reserves and the availability of funds in the banking system, which places downward pressure on interest rates. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013) 5•21 FIVE • ECONOMIC POLICY 5. Discuss the challenges governments face in their fiscal and monetary policies and the consequences of failed policy. • One challenge the government faces is that the economy may be slow to react to policy changes. As a consequence, interventionist policy may not be effective or even essential in guiding the economy in the right direction. • A second challenge is the view that the economy makes its way quickly to its natural equilibrium, and that no need exists for policy other than to constrain policy. • Interest payments on the national debt were the federal government’s single biggest expenditure throughout most of the 1990s. However, successive budget surpluses in the late 2000s helped to lower the federal government’s overall debt position. • Fiscal and monetary policies are often unsynchronized, increasing the cost to the economy. The late 1980s saw rising provincial and federal deficits at a time when the economy was growing strongly and inflationary pressure was building. • The Bank of Canada responded by raising interest rates, which resulted in higher debt servicing costs for governments. Online Frequently Asked Questions CSI has answered many frequently asked questions about this Chapter. Read through online Module 5 FAQs. Online Post-Module Assessment Once you have completed the chapter, take the Module 5 Post-Test. © CSI GLOBAL EDUCATION INC. (2013)