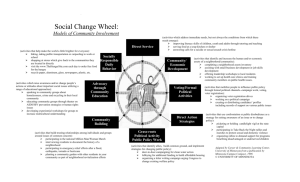

Community Transformation - Asset-Based Community Development

advertisement