digging up the african-american past: historical archaeology

advertisement

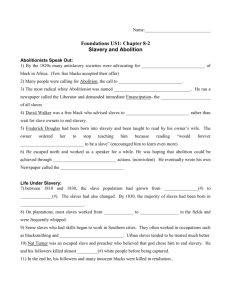

DIGGING UP THEAFRICAN-AMERICAN PAST: AND HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPHY SLAVERY ARCHAEOLOGY, Shane White UncommonGround: Archaeology and Early AfricanAmerica, 1659-1800. By Leland Ferguson, SmithsonianInstitutionPress, Washington, 1992, pp. xlv + 186, US$35.00 (cloth) and US$14.95 (paper). WaterfromtheRock: Black Resistancein a Revolutionary Age. By Sylvia R. Frey, Princeton UniversityPress, Princeton, 1991, pp. xii + 376, US$29.95. Life in theAntebellumSouth. Edited by Edward BeforeFreedom Came: African-American D. C. Campbell, Jr.withKym S. Rice, UniversityPress of Virginia,Charlottesville,1991, pp. xv + 219, US$19.95. of freeblacks establisheditself New England, a small settlement In late eighteenth-century at PartingWays, neartheforkin theroad fromPlymouthto Plympton.In pre-Revolutionary times,the residentsof thiscommunity- Cato Howe, Prince Goodwin, Plato Turner and Quamany - had been slaves in society in which blacks were a very small minorityof the population;duringtheRevolutiontheyhad foughtin theContinentalArmy.On bothgrounds we would expect themto be fairlywell acculturatedto white society. Yet evidence from an archaeological dig at Parting Ways hintsat a more complex picture. Although the community'shouses were builtof much the same materialas othersin New England, their twelve-footfloorpattern, It utilisedan Africanor African-American design was different. ratherthan the sixteenfoot patterntypical of Anglo-Americandwellings. Furthermore, the fourhouses were clusteredtogetherat the intersectionof the blocks, an arrangement thatquite possiblyreflectedthemore communalpatternsof Africa.1There are indications, then,thatafterlivinga good proportionof theirlives as slaves withina whiteNew England society these blacks, on regainingfull controlof theirlives, drew on theirAfrican past to build a settlementthat,in importantways, was at variance withthose of theirYankee neighbours. The example of PartingWays points to the varied and eclectic natureof the evidence thathistoriansinvestigatingthe lives of AfricanAmericans in the American colonies and in the early years of the new nationhave to examine. Few slaves could read and write;2 foreven fewerwas it thecase thatwhattheydid writewas likelyto survive. These simple facts provide the major intellectualchallenge for those attemptingto recover the black and ambiguous- allusive rather past. Evidence is almostinvariablyhardwon, fragmentary, and thandefinitive.Interdisciplinary imaginationare requiredto tease out its full analysis materials must and eighteenth-century with seventeenthwho work Those significance. look withenvious eyes at thecornucopiaof evidence (in particulartheW.P.A. interviews) available to historiansof later periods. Historianshave metthischallengein a numberof well-knownways, bothreinterpreting old sources with new methodsand uncoveringnew types of evidence. For a long time now historicalarchaeology has appeared (at least to me) to offerthe most promise of 37 of turning up new materialthatcan helpdeepenour knowledgeof slavery,particularly thedetailsof everydayslave life,thesortsof thingsnotcommonlymentioned in either oralorwritten sources.Untilrecently, theveryhighcostofconducting excavations, lengthy timelags beforematerialis publishedand thusmade available to thosewho are not of historicalarchaeologists to ask questionsof theirmaterial 'insiders',and a tendency thatsometimesseemeitherobtuseor obscure,have combinedto limittheutility of their workforotherscholars.However,a new generationof historicalarchaeologists, with a moresophisticated of the historiography of slaveryand an abilityto understanding minimise thatdo notjustillustrate what jargon,hasbegun,now,tocomeup withfindings we alreadyknow,butextendand challengeour understanding of some crucialaspects of slavery.3Historicalarchaeologists are beginningto deliverthegoods and historians woulddo well to pay attention to theirwork. LelandFergusonbeginsUncommon Ground:Archaeology and EarlyAfrican America, 1650-1800 witha briefaccountof theshorthistoryof African-American archaeology. To all intentsand purposesit originated in the 1960s whentheCivil Rightsmovement proddedscholarsintoa realisationthatblackAmericanswerepartof thecolonialpast. In 1967 CharlesFairbankswas contracted by Florida State Park Serviceto excavate andunderFairbanks'influence theUniversity ofFloridabecamethe Kingsmillplantation centreof whathe called 'plantation The of feelingconcerning archaeology'. groundswell the historicalexperienceof blacks in Americathatflowedon fromthe Civil Rights movement thefederalgovernment to interpret theNationalHistoricPreservation pressured Act so as to includeAfricanAmericanarchaeologicalremains.As a result,many conductedtheirfieldwork archaeologists just ahead of thebulldozeron federally-funded construction In the 1970s and 1980s mosthistoricalarchaeologists weredoing projects. workon a contract basis.Theyaccumulated of data to submit and,required hugequantities took their lead from the social scientists then the reports, dominating discipline,working out listsof artifact therateat whichslavespickedup European frequencies, measuring to demonstrate thedifferent economicstatusof slaves and traits,and usingtheartifacts theirowners.As Fergusontartly concludesin relationto theiractivities, someofthedata and interpretations are useful,buttheirmoregeneralconclusions'are of littleanthropologicalor historicalinterest'(p. xi). In Uncommon GroundLeland Ferguson,influenced over by theworkof historians thelastdecadeor so (and hereI shouldadd thatthishistorian was a bitunnerved to have his profession held up as theepitomeof sweetnessand lightin manyof the constantly author'sintradisciplinary turfbattles),setsoutto writean introductory bookthatis 'wide and not a review of but an of newly ranging speculative; completedresearch, offering discoveredawareness,ideasandthings'(p. xxxiv).His mainconcernsare withpotsand aboutwhichAfricanAmericanarchaeologists have housing,thetwoclasses of artifacts amassedthemostknowledge. It was in the 1930s thatarchaeologists at Williamsburg and surrounding plantations firstfoundfragments ofclaypotsusedbyslaves.In 1962IvorNöel Hume,fromColonial Williamsburg, publisheda paperin whichhe arguedthatthesevesselshad been made free Indians. Nöel Hume,afterconcludingthattheastuteIndiansmayhave founda by marketamongtheslaves,labelledtheartifacts Colono-IndianWare. This remainedthe conventionalwisdomwell intothe 1970s when the sheer quantityof materialbeing recoveredin SouthCarolinaforceda reconsideration. HereFerguson'saccountbecomes withfaintechoesof IndianaJones,buthe and otherswereable to just a bitbreathless, 38 show, by lookingat potsmade in Africaand searchingthewrittenrecordas well as analysing thousandsof bitsof pottery,thatslaves made potsin America. Not all were made by African Americans- some were clearlyNative American- butmorethanenoughwere to warrant Ferguson proposingthatthe 'Indian' be dropped and the artifactslabelled simplyColono Ware. The fragmentsfoundwere almost invariablyfrombowls and not plates, hintingat a ratherdifferentpatternof foodways from thatof the Europeans. But Ferguson's most fascinatingfindingabout the use of Colono Ware concernsa small numberof bowls from South Carolina marked with a simple cross or a cross enclosed in a circle on the base. Most of these pieces were discovered not around slave quartersbut in rivers adjacent to old rice plantations.Ferguson suggeststhatthe marksare Bakongo cosmograms and that thesesmall bowls containedsacred medicinesor minkisiand were used in ritualsinvolving the ubiquitous West African water spirits. If he is correct, and his argumentappears of thecontinuedimportance convincing,thenthesemarksare a quite strikingdemonstration of some African ways in the South Carolina low country. Housing is the othertype,of evidence which archaelogistshave investigatedin some detail. Althoughmost of our knowledge concerns the antebellumperiod there has been sites. Slave houses foundin theCarolina lowlands, some excavationof eighteenth-century fromotherstructuresfoundin colonial America. at Yaughaii and Curriboo,were different The houses had clay walls similarto those foundin Africa. Nearby pits were used initially as a source for clay for daubing the walls and later to hold rubbish. By the nineteenth centurythe structureswere takingon some European features,particularlychimneys,but the houses remainedvery small, much smaller than those found in Virginia. Again this appears to reflectAfricanculturalpatterns Europeans lived inside theirhouses, but for AfricanAmericans most activities occurred in the yards around their dwellings. Some of the details in UncommonGround are new, but Ferguson's major contention about theimportanceof theAfricanpast in the lives of slaves in mainlandNorthAmerica contains few surprisesfor anyone versed in the historiographyof slavery over the last decade or so. However, forthisreviewer,at least, it was the author's material,both from his own researchand thatof others,highlightingthe fluidityand contingencyof AfricanAmericanculturethatwas mostnovel and interesting.In particular,theevidence pointing to Native American influencein the formationof African-Americanculturehelps to draw out a factorthatis oftenhintedat, butneverreallydeveloped fiillyin theworkof historians relyingon the writtenrecord. It appears thatthe old idea of a segregated existence, implicitin the label 'ColonoIndianWare', was mistakenand thatto a much greaterextentthanhistorianshad previously thoughttherewas a three-wayculturalcontact occurringin colonial America. Perhaps the earliest example of this process, althoughthis is still a controversialinterpretation, involvespipes made in seventeenth-century Virginia.MatthewEmerson,a studentof James from fifteensites in the colony. He concluded that bowls 694 re-examined Deetz, pipe was of the the European and thatthedecorationswere predominantly pipes shape basically Native American influence.Most of these pipes demonstrated also but that African, they were made in the late seventeenthcenturywhen whites and blacks lived in very close contact; locally made pipes declined and disappeared early in the eighteenthcenturyas plantationlife became more segregated and European pipes more readily available. 39 One of thebestexamples of thecreationof thiscreole cultureis containedin Ferguson's fascinatingdiscussion of the foodways of South Carolina blacks in which he shows how Native American, Africanand European influencescombined withinthe constraintsof slavery to shape theirdistinctiveculinarypractices. Basically, therewas a change from an Africandietof rice, milletand manioc to one centredon corn (even in therice colonies, forrice was a valuable cash crop), withsupplementsfromgame theywere able to snare. Whites served food on plattersand plates, but slaves used theirfingersand ate froma varietyof bowls. Historical archaeologistsare also able to provide evidence about the timingof cultural developments.For example, in South Carolina the incidence of Colono Ware, ubiquitous in eighteenth-century sites, drops markedlyafterthe beginningof the nineteenthcentury. A numberof factors- theend of theAfricanslave trade,theincreasingawareness among AfricanAmericans of glazed and highlyfiredpottery,and the increased availability of industriallymanufacturedceramics - combined to diminishthe importanceof plantation made-pottery.In thenineteenthcentury,thedemand forColono Ware bowls - theywere highlyvalued forcooking African-American dishes such as okra - was met by itinerant Catawba Indians. Althoughthe point is not discussed by Ferguson, implicitin much of the materialhe adduces is a sense of the interactionbetween slaves and the fundamentaltransformation of the economies of the North Atlantic World during the eighteenthand nineteenth centuries. The issue this raises, of course, concerns the extentto which the consumer revolution affectedthe life of North American slaves. Were African-American craft traditionsrenderedincreasinglyobsolete by thepenetrationof cheaplymanufactured goods intothemarketof theslave South?The evidence fromseventeenth-century Virginianpipes and Colono Ware certainlysuggests thatthis was the case. There is, however, at least one area where the situationwas rathermore complicated. In the colonial period slaves wore garmentswhichwere eithermade by themselvesfromcheap importedclothor were, with surprisingfrequency,as the runaway advertisementsindicate, ready-made. This changed in the last decades of the eighteenthcentury.Startingwiththe non-importation movementduringthe Revolution and gaining momentumin the years afterthe invention of the cottongin and the rapid expansion in the growthof cotton,thisaspect of slave life was transformed.By the timethe ex-slaves who would be interviewedin the 1930s were growingup in the 1850s and 1860s, theirparents,particularlytheirmothers,were weaving clothand makingtheirclothes. Testimonyfromtheex-slaves is filledwithpages of detailed descriptionsof the hours spent weaving cloth, manufacturingdyes fromvarious leaves and berries,and tanningleatherto make shoes. To be sure, store-bought clothesand shoes were highlyvalued and any extra money earned in the slaves' own time was frequently craftthatexpanded spenton them,butitis stillthecase thatthiswas one African-American in antebellumyears. There is a certainamount of idiosyncrasyin Uncommon Ground. Althougha short book, it sprawls with not particularlywell-organised chapters. Twice the author uses fictionalisedrecreationsto illustratehis point (a strategywhich, to my surprise,I found helpfulon thesecond occasion). The Epilogue, a confessionalaccountcentredon theeightyear-oldFergusonand a friendusing theword 'nigger' to a black railroadworkerin 1949, while interestingenough, seemed barely relevant.But the book is certainlyengagingand easy to read, and it effectivelyconveys to outsidersa sense of the potentialof historical 40 archaeology for those interestedin the African-Americanpast. Hopefully historians, particularlythose unfamiliarwith the work of historical archaeologists, will read it. ' Sylvia Frey s WaterFrom theRock: Black Resistance in a RevolutionaryAge illustrates well the range and varietyof evidence thathistoriansneed to piece togetherin order to attemptto recover the black past. Her research in writtensources, particularlyarchival material concerning the conduct of British operations in America, is little short of prodigious,and she has turnedup much new informationabout AfricanAmericans. The sensitiveto thepossibilitiesin theworkof historicalarchaeologists authoris also particularly and frequentlyincorporatestheirfindingsinto her account. Sylvia Frey's thesis can be simplystated:to a muchgreaterextentthanmosthistorianshad previouslythought,African Americanswere closely involved in the American Revolutionin the South. In her words, '... a black liberationmovementwas central to the revolutionarystrugglein the South, and thefailureofthatmovementdid notdissipate theblack revolutionarypotential,which re-emergedin the postwar period as a strugglefor cultural power' (p. 4). Frey shows how blacks in the years after 1765 were swept up by 'the force of ideological energy' (p. 49), and how thecolonists' fearof black restivenessshaped Britain's southernstrategy. Her account of the role blacks played in the Revolution in the South, of the incredible disruptioncaused by what was oftena vicious civil war, and of the way some Southern slaves, carryingwiththema distinctiveAfrican-American cultureparticularlyin the area of religion, ended up in all sorts of obscure places in the aftermathof the Revolution, is an importantcontributionto the historiography. Accordingto the author,in the early years of the New Republic, evangelical religion playeda crucialrole in theshiftfroma patriarchalto a paternalistsystem.Once theBaptists and Methodistsacknowledgedtheirfailureand shuckedofftheirhostilitytowardsslavery, theybecame 'increasinglyinfluentialin shapingthepaternalisticethos thatwas to become markof an antebellumsociety' (p. 244). The result,Frey argues, was the distinguishing a 'gradual ameliorationof some aspects of slavery' (p. 280). Evidence from historical archaeology of the replacementof African style housing with frame housing, even the raised wooden flooringon some plantationsand a shiftfromColono Ware to imported European ceramics, supportsher contention.If evangelical religionofferedslaveholders a way to live withthe moral problems of slavery, it meant somethingratherdifferentto the slaves. For them,it was a symbolicassertionof self,a way of transcendingtheirstatus in a slave society. Religion became the centrepieceof theirculture.Southernblacks were thwartedin the Revolution,but theirhopes for freedombecame increasinglytied up in culturalassertionin ways thatranged fromthe rise of uñsanctionedcommercial activity by slaves to the establishmentof separate black churches. Thus in Frey's account, the AmericanRevolutionwas a pivotalmomentin African-Americanhistoryas well, and that most mythicof American events no longer has to carrythe burden of a JimCrow past. As is probablyapparentby now I had mixed reactionsto thisbook. The middle section, dealing with the Revolution, is exhaustively researched and as comprehensive and convincingan account of the role blacks played in the struggleas one could hope to find, but in therestof thebook, althoughtherewere useful insights,I was oftenleftstruggling. Much of my unease stems fromProfessorFrey's ideas about the natureof black culture and my differenceswith her over the sorts of conclusions that can be drawn from and imperfectevidence. What I would like to do here, by way of illustration, fragmentary in some detail at a couple of issues raised by Frey's opening chapter, a forty look to is page surveyof slavery and black culture in the pre-RevolutionarySouth. 41 of theAfrican assertsthattherewas a 'systematic The authorrepeatedly repression is the'strikingly heritage'(p. 36). The mainevidenceadducedto supportthisproposition or African-derived ritualobjectsinarchaeological apparent... absenceofAfrican-related depositswheretheywouldbe expectedto appear'(p. 36). Shealso claimsthat'thematerial bytheslave regime'(p. 36), and expressionsof Africanreligionwerelargelydestroyed later,thattheevidencecollectedfromburialgroundsin Marylandand Virginiafromthe late seventeenth to theearlynineteenth centuriesshows'minimalAfricaninfluence and of Africanpractices'(p. 40). This line of argument is suggests]theforcedextinction intotheperiodaftertheRevolution:in thelastchapterof thebookFrey carriedthrough talksof a 'massiveprogramof culturalgenocidedevelopedand efficiently managedby slaveowners'(p. 285). ProfessorFrey's quitestartling claimsaboutthesuppression of Africanculturein the colonialperiodappeartobe basedon a misunderstanding ofthesortofevidencehistorical are likelyto turnup. Archaeologists archaeologists diggingthroughslave quartersare usuallyonlygoingto findobjectsthathavebeenabandoned,discardedor lost.Not even all oftheseare goingto survive;basketry and itemsmadeof woodor clothremainintact in the most Further,thingsthathold underground only exceptionalcircumstances.4 are more value to be on than left for Excavations particular likely passed archaeologists. on theJordan in Texas a of illustration these Here Kenneth plantation provide good points. Brownand Doreen Cooplerdid actuallyfinda collectionof artifacts probablyused in and divination rituals. The forced and abandonment of the sitebytheblack healing abrupt residents,theyargued, led to the discoveryof objects usually not presentin the record.5Butthiswas atypical.In short,thesortofartifacts archaeological Freyapparently seeksinexcavations ofslavequarters probablywouldnotevenbe foundintheexcavation of mosteighteenth-century West Africanvillages. ButI thinkrathermoreis involvedherethanProfessor Frey'sunrealistic expectations of whathistoricalarchaeologists shoulduncover.Implicitin muchof herdiscussionof slavecultureis an assumption thatAfricanculturesurvivedthemiddlepassagepretty well to fall foul of an and interventionist white intact,only oppressive slaveowningregime. theslaveownersmoretolerant My own viewis thattheslave tradewas moretraumatic, of thecultureof theslaves (notfromanyfeelingsof benevolence,butbecausetheyhad otherconcerns),and thattheterm'AfricanAmerican',withitssuggestion of a dynamic creoleculture,is thecorrectone. Thereis no needtoembracefullyStanleyElkins'famousthesisinordertoacknowledge theprofoundly slaves. shocking impactoftheslavetradeandthemiddlepassageon African Evidencefroma varietyof sourceshintsat themassiveculturaldisruption thatinevitably ensued. Excavationsat the seventeenth-century sitesof Pettusand Utopia in Virginia uncoveredpottery madeby slavesthatwas of a verypoorquality.As LelandFerguson of asked,how could WestAfricans,comingfroma culturewitha tradition pertinently finehandbuilt makethesecrudeexamples?Similarly,TheresaSingletonpoints pottery, out thatAfricanceramicswere elaborately,even ostentatiously, decoratedand thatby African-American were almost bereft of decoration.6 A thirdexample comparison pots of thisprocessconcerns'countrymarks'or ritualscarifications. These bodyand racial are frequently foundon African-born slaves,butto myknowledgeat least,no markings one has foundthemon an American-born slave. 42 The explanationforthese and otherculturaltransformations does not lie in anything in black lives on seventeenth-and eighteenth-century as crude as directwhiteinterference plantations.To be sure, slaveowners and officials clamped down on anything,such as large gatheringsfor funeralsor the banging of drums thathad the potential to foment rebellion, but I have never seen any evidence of slaveowners or overseers forbidding, forexample, ritualscarifications.Even had theydone so it is doubtfulthatbanning the practice could have been so completely successful that not one slave shows up in the historicalrecord as being so marked. A more satisfyingexplanation can be found in the natureof the slave trade and the circumstancesin which Africans found themselves in the New World. Although some areas in mainlandBritishNorthAmerica did end up with concentrationsof slaves from the same region in Africa- forexample Kongo-Angola was a very importantsource for South Carolina slaves - slavers deliberatelymixed the ethnicmake-up of theircargoes as a safetymeasure. Probablyeven more importantwas theyouthof slave cargoes, a factor thathas received littleemphasis in thehistoriographyof slavery. The purpose of the slave tradewas to supplylabourers; about two-thirdsof slaves undergoingthe 'middle passage' were males and mostwere eitherteenagersor in theirearly twenties.In seventeenth-and West Africa,as Leland Fergusonpointsout,potterywas generallymade eighteenth-century by female specialists,who thentradedtheirgoods. Young girls fromfamilies who made these wares learnedthecraft,but the majorityof Africansprobablydid not. The chances were againstany one plantationin seventeenth-century Virginiaor earlyeighteenth-century South Carolina endingup witha skilled Africanpotter.On theotherhand, most Africans would have had some idea about the basic materials and techniques. And, to speculate further,such people, if theysought to make pots, were probably more open to picking up practicesfromNative Americans or Europeans than someone who knew exactly what they were doing. African culturewas based on an integratedview of the world, a view thatthe slave tradeand enslavementin the New World turnedupside down. Subjected to slavery, with the consequent loss of controlof theirlives (a loss thatwas doubtless particularlyacute for males resultingin masculine feelingsof inadequacy and frustration),it is likely that Africanswould have seen initiationceremoniesand ritualscarification,signallingthe rite of passage to manhood, as wildly inappropriate.What survived in the New World was not Africancultureas such, but the elements of African culturethatwere useful in the settingof the plantation.These were combined with what was already present in the Americas to forma new and dynamiccreole culturethatwe now call African-American. Colono Ware was anythingbut a replica of West African pottery.It was a response to new conditionsand thatis why,forexample, Colono Ware fromVirginia was much more influencedby European ideas of formand shape than thatfound in South Carolina. It is also whypotteryfromtheSouth,in contrastto thatof West Africa,was almostcompletely undecorated. African-American culturewas fluid and dynamic. It was also contingent,constantly respondingto theconditionsin whichAfricanAmericansfoundthemselves.Because those conditionsvaried considerablythroughoutthe New World, historiansmustbe extremely wary of assumingthata generalised patternbased on what happened in Africa or in the West Indies would necessarilyoccur in Virginia, South Carolina or New York. Sylvia Frey's studyillustratestheproblem. In themiddle of a good discussion of the slave family 43 in thepre-Revolutionary Southshe claims that'(p)olygyny,a respectedand formally WestAfrica,was alsoprevalent sanctioned theSouth' arrangement throughout throughout (p. 34, myemphasis).Quite possiblythiswas thecase. The black familyis probably the most politicallycharged area of African-American and not historiography, is mostin needof re-evaluation, butit is stillthecase thatthereis little coincidentally, knownevidenceto supporthercontention. Freycitesone examplefromRichardDunn's studyof Mt. Tayloe in nineteenth-century Virginia.This case and theotherone Dunn foundmay well turnout to be cruciallyimportant, but theyhardlydemonstrate the in thepre-Revolutionary South. 'prevalence'of polygyny Theotherassumption in muchoftherecentworkofAfricanAmericanculture implicit is a modelof declension.Africaninfluencewas at its peak at some timeearlyin the and thereafter in importance. diminished The corollaryis thatifone eighteenth century inthenineteenth-century, can findsomething inthiscase a polygynous union,thenitmust haveexistedearlierinthecolonialperiod.Thisreviewerremainsunconvinced thatculture travelsin suchconveniently lines.RogerBastide'sconclusionthatreligiouscults straight shouldbe viewed*... as a seriesof discontinuous and events,of traditions interrupted Americanculturein theUnited recovered',couldhave a broaderapplicationto Africanin theyearsbefore1808 whentheslave tradeofficially ended. States,particularly Changedcircumstances maywell havemadepracticesretainedonlyin thecollective ofAfrican Americans JamesDeetz's workat FlowerdewHundred memory newlyrelevant. uncovered a strong correlation betweentheincidence ofColonoWareandtheestablishment of separatehousingforslavesin thelateseventeenth Thissuggeststhatoncethe century. situation of slaveschangedand theywereremovedfroma veryclose contactwiththeir whiteownerstheybeganto maketheirown bowls. Similarly,theblacksmentioned at thebeginning ofthisessaywhosettledat PartingWaysin New Englanddrewon African culturalpatterns oncetheyregainedcontroloftheirlives.I suspectthatwhen,intheearly decadesof thenineteenth century,slaves began in greaternumbersto maketheirown clothesthismayalso havebrought to thesurfaceagainmemoriesofhowto makevarious from such as berries,leaves and barkthatlay close to hand. dyes ingredients Withthethirdstudyunderreviewhere,thefocusshiftsforwardsto slaveryin the antebellum period.BeforeFreedomCame is a book designedto accompanya museum exhibition in Richmond,Virginia,which organisedby theMuseumof theConfederacy was on view in Richmondand thenwas shown in Columbia, South Carolina and Ohio. Usually,it is ratherhardto takethetextin books thataccompany Wilberforce, - something exhibitions tooseriously aboutthelargesize format, theglossypaperor the abundanceof picturessignalsthatthereaderis expectedto browseand notto read. In thiscase, though,thatwould be a mistake.Six well-knownscholarshave provided substantial essaysof an impressively highstandard.Drew GilpinFaustoutlinestherole has slavery playedin theAmericanschemeof things;JohnMichaelVlachuses an array ofsourcestodescribethesetting oftheplantation; DeborahGrayWhitereprises herearlier workto givean accountof femaleslaves; CharlesJoyner describestheplantation world of slaves,judiciouslybalancingblackcreativeachievements withtheconstraints imposed better-known forhisworkinthetwentieth byslavery;DavidR. Goldfield, probably century, a fine account of urban in the antebellum gives South,andinthefinalpieceTheresa slavery A. Singleton offers an excellentassessment ofthecontribution thathistorical archaeology can maketo understanding I am not certain how useful thevolumewill prove slavery. forcasual exhibition-goers, but therecan be littledoubtof its value in theuniversity. 44 It will be ideal for good studentsin surveyand black historycourses who wish to learn about antebellumslavery. Withall due respectto theauthors,though,it is notjust theessays thatmake thisbook such good value formoney. What lingersin the mind when one puts the book down are the 170 illustrations,woodcuts, paintingsand, in particular,photographs,taken fromthe exhibitionitself.Some of theimages are well-known,othersless so; buttheyare all worthy of the attentionof anyone interestedin the South or the black experience in America. Historianshave nottakenfulladvantageof visual materialin theirattemptsto uncover the African-Americanpast. Occasionally they have highlightedtheir argumentwith a particularlyapposite image thephotographof fivegenerationsof a slave familytellingly used on the cover of HerbertG. Gutman's The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925 (1976) is a notable example - but generally illustrationsappear to be an ratherthan an integralpart of theiranalyses. The mechanics and costs of afterthought book production,withphotographsusually segregatedfromthe text,have hardlyhelped this process. In the case of Before Freedom Came, the illustrationsare spread through the book, but the discussions of their meaning are disappointinglyinfrequent,and the materialis set out in such a way thatalmost invariablyone has to turna page to findthe image being referredto. The principalanalyticaluse of visual materialhas been in studiesof 'the black image in the whitemind'. There are a numberof outstandingstudiesof paintings,in particular, whichreveal muchabout theassumptionsand attitudes butalso woodcutsand illustrations, of whitestowardsblacks.7More recentlya numberof scholarshave publishedworkdealing thosetakenin the 1930s, but here,as in thecase of painting, withphotographs,particularly theyhave placed the emphasis on the assumptionsand intentionsof the person creating thepaintingor photograph.This is obviouslyimportant,perhapseven crucial, but it leaves unansweredthe questionof whetherpaintingsand photographscan tell us anythingabout the person or object being represented. There is scope for the historianto use images of slaves, particularlyphotographs,in differentand rathermore illuminatingways. Whatever reservationsone may have about The Civil War television documentaryas history,it would be churlishto deny that the techniques used by Ken Burns infusednew life into hundredsof photographs.Such an effectiveuse of themediummightmake historianswonderwhethertheyhave been glossing over a potentially useful source. Extremely imaginative in their use of runaway advertisements,which, of course, are essentiallyverbal descriptionsof slaves, historians should be able, with a little inventivenessand skill, to use the hundreds of existing photographsof slaves as evidence and not merely illustrations. One possible way of achieving this is by viewing the bodies of slaves as a source. observerswere certainlywell aware thattherewas somethingdistinctive Nineteenth-century in theappearance of blacks otherthanskincolour. Confrontedforthe firsttimeby a large numberof blacks in themarketsof WashingtonD.C. in the 1850s, FrederickLaw Olmstead concluded that 4[i]n theirdress, language, manner, motions- all were distinguishable almostas much by theircolour, fromthewhitepeople who were distributedamong them, and engaged in the same occupations'.8 The way in which AfricanAmericans presented theirbodies to themselves,to whitesand to photographers,the way theywalked, talked, dressed and styledtheirhair was significantand offersa point of entryinto theirworld that may reveal somethingnew about African-Americanculture. 45 or otherness notedbyOlmsteadpervadessomeof thephotoThe senseof difference image (on p. 10) about two graphsin BeforeFreedomCame. In one eye-catching dozenmaleandfemalelabourerswalkhomefromthefieldson theWoodlandsplantation nearCharleston.On theheadsof all buta coupleof themalesare largeloads of cotton. The singlefileof slave s curvesfromtherightmiddlegroundacrossthepictureandthen on theslave driverin front.Dressedin backto therightforeground, focusingattention a tophat,a frockcoatanda whiteshirt,garbverysimilartothatoftheslavedriverwhom sketchedwithhisdrawingmachinethreedecadesearlier Basil Hall, an Englishtraveller, on p. 55), and holdingsomesortof stick,he cutsa striking (a sketchreproduced figure. has toldhis subjectsto be by thepositionof theslaves' feet,thephotographer Judging stillwhilehe takesthepicture,butthedriver,unliketheotherslaves who are looking offtherightmarginofthephotograph. at thecamera,gazes resolutely WithotherphotoAs TheresaSingraphsitis less theoverallimpactand morethedetailthatis important. takenat Drayton gletonpointsout, at least fiveof thewomenin an 1862 photograph HiltonHead, SouthCarolina(on p. 163) arewearingbeadednecklaces.Charm plantation, as oneAfricanAmerican, MollieDawson,remembered, '... was supposedtobring strings, good luckterde ownerof it'. Similarly,I have spenta considerableamountof timereand paintings to findoutmoreabouttheshoesexcentlyexamining photographs trying slavesspentso muchtimediscussingin theW.P.A. interviews. Thusfarmyconclusion thanthatitis amazinghow manyslaveswerephotographed is no moremomentous with or theirfeetobscured shovels whatever else close to foot. There furrows, is, however, by lay in thefuture. enoughevidenceto suggestthatsuchan approachmaywell provefruitful blacks(andforthatmatter womenandtheworking class)backintotheirrightful Writing in the of America involves a eclectic story place necessarily highly approach.Faced with sourcesthatare oftenopaque and intransigent, historians haveborrowedfromanynumberofotherdisciplinesinordertoteasemeaningoutofwhattheyalreadyhaveor tocome andvitality ofthehistoriogup withnewevidence.Thisis wheremuchoftheexcitement of African Americans lies. It is also an that can test the raphy enterprise patienceofothers. historians have so to the Thankfully, though, nothing precious well-beingof thefuture of Americancultureas thecanonto protect,and history has suffered onlya fewcranky outbursts ratherthanthesustainedassaultsof AllanBloomand his ilkthatliterature has hadto putup with.9The potential forthecontinuation of thishealthyprocessof interdisif scholarsof slaveryand ciplinaryscholarshipremainshigh,and it will be surprising theAfricanAmericanpastdo notheara lotmorefromhistoricalarchaelogists and those as evidencein thenextfewyears. usingphotographs NOTES 1. JamesDeetz,In SmallThingsForgotten: TheArchaeology ofEarlyAmericanLife,AnchorBooks,Garden City,New York, 1977, pp. 138-54. 2. See JanetDuitsmanCornelius,WhenI Can Read My TitleClear: Literacy,Slaveryand Religionin the Antebellum of SouthCarolinaPress,Columbia,1991. South,University 3. A specialissueofHistoricalArchaeology, on southern xxiv,1990,devotedtohistorical archaeology plantationsand farms,givesa good idea of someof theworkbeingdone. TheresaA. Singleton'sessay, "The ofthePlantation South:A ReviewofApproachesandGoals', pp. 70-7, inparticular, is well Archaeology worthreading. 4. TheresaA. Singleton, 'The Archaeology ofSlaveLife',inEdwardD.C. Campbell,Jr.(ed.), BeforeFreedom Came:African-American PressofVirginia,Charlottesville, South,University Lifein theAntebellum 1991, p. 155. 5. Kenneth L. BrownandDoreenC. Cooper,'Structural inan African-American SlaveandTenant Continuity HistoricalArchaeology,xxiv, 1990, pp. 7-19. Community', 6. Singleton,4TheArchaeologyof Slave Life*,p. 161. She is relyinghereon theworkof MatthewHill. 46 Art:VolIV FromtheAmericanRevo7. See, inparticular, HughHonour,TheImageoftheBlackin Western lutionto WorldWarI. Part I, Slavesand LiberatorsandPart2, BlackModelsand WhiteMyths,Harvard Press,Cambridge,Mass., 1989. For further proofthatthereare exhibition University cataloguesworth readingand fora notableincursionintothisarea by an historian,see PeterH. Wood and KarenC.C. ofTexas Homer'sImagesofBlacks:TheCivilWarand Reconstruction Years,University Dalton,Winslow Press,Austin,1990. on Cottonand Slaveryin the 8. FrederickLaw Olmstead,TheCottonKingdom:A Traveller'sObservations AmericanSlave States,editedby ArthurM. Schlesinger,AlfredA. Knopf,New York, 1953, p. 28. thecanon,andthecontroversies, see HenryLouis on AfricanAmericans, comments 9. For someinteresting AmericanTradition',in Dominick and theAfroGates,Jr.,The Master'sPieces: On Canon Formation on Hegemony and Resistance,CornellUniversity Press, LaCapra(ed.), TheBoundsofRace: Perspectives Ithacaand London, 1991, pp. 17-38. 47