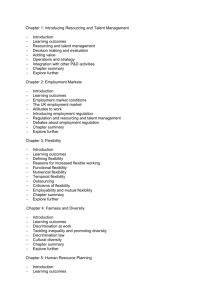

Recruitment, retention and turnover

advertisement