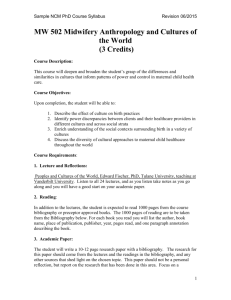

Giving Birth to Misconceptions - Senior Theses, Papers & Projects

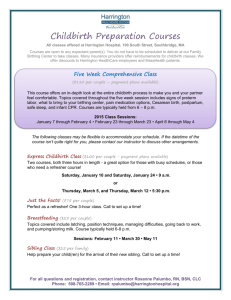

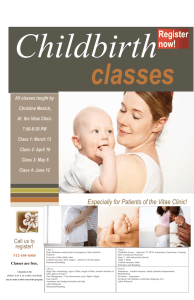

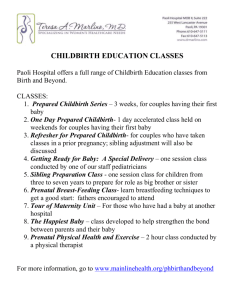

advertisement