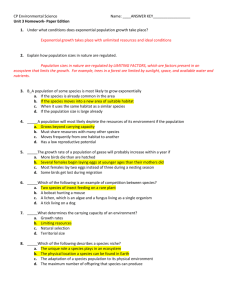

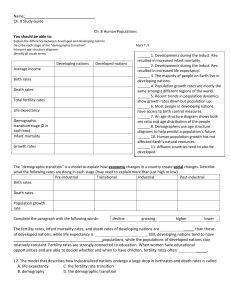

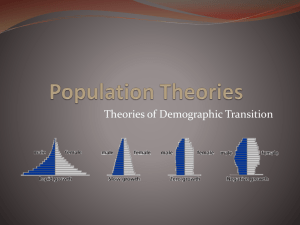

Fertility as a process of social change

advertisement