Customs of Gender Crossing

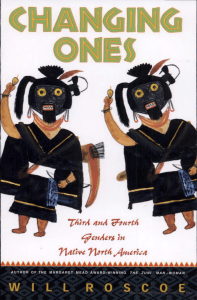

To discover that many cultures have had gender crossing institutionalized among their people shows an

incredible amount of insight into and tolerance of general human behavior. In order to be

“institutionalized,” it is expected by a culture that some people will adopt characteristics that are

considered to belong to the opposite sex. Instead of ostracizing a person upon such occurrences, their

alternative sexual identity is accepted and then accommodated within society. In these forms of society

it is not uncommon for there to exist a third or fourth gender.

The article “The Berdache Tradition” by Walter L. Williams discusses the additional sexual identities that

exist in many aboriginal New World societies. The morphological male that does not show the various

aspects fitting within his society’s man’s role, usually due to nonmasculine and/or androgynous

characteristics, is commonly referred to as a “berdache.” Instead of being viewed as an outcast by his

fellow people, a berdache gains social prestige, as they are considered to hold unique spiritual,

intellectual or artistic gifts.

For the Mohave of the Colorado River Valley, in order to identify the berdache spirit, juvenile males that

exhibit the expected characteristics between the ages of nine and twelve are to be tested in a public

ceremony. These ceremonies allow an acknowledgement and/or proving of the child’s berdache status, if

it exists. The child’s personality preferences are tested and observed through aspects such as his way of

dancing (does he dance like a woman?), pursuit of female objects or crafts (baskets over bows and

arrows), cooking, desired dress, and other natural behavioral characteristics of the boy. What allows

these tests to be so powerful and effective is that the berdache role is never in any way forced upon the

youth. Also, children are well aware of the implications of the ceremonies beforehand, holding a mature

grasp of their decision and even the ways in which it will change life’s course.

Response: Sexual divisions of labor

I feel that it’s important to more clearly address how one sex’s role could not exist without the other. I

know that it is clearly implied, but in most cultures a woman cannot support her children without also

having the support that a man (or men) provides --a perfect example of this was detailed last week

through descriptions of the Bari peoples. Contrarily, a husband would have little reason to perform the

many undertakings within his given role unless he had a wife performing her own specific types of labor.

At the risk of oversimplifying things, it seems that on a very fundamental level, many aspects of these

gender- and/or sex-roles can come down to the simple fact that women can bear children while men

cannot.

When you said, “I don’t think that they were saying that women are not as important, but … that a

woman’s work is not as valued as the man’s work,” I sense that you are getting closer to addressing the

relative brevity of this week’s reading material in regards to this substantial topic of gender roles (and

even universal subordination). The types of work assigned to the male and female in a given culture are

inherently different based on need; it’s probably ridiculous for one to claim to be of greater importance

than the other.