REPORT ON THE OBSERVANCE OF STANDARDS

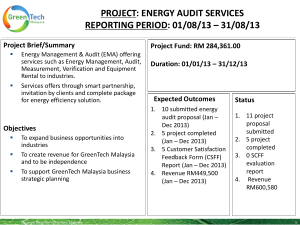

advertisement