Cover Sheet - Independent Evaluation Group

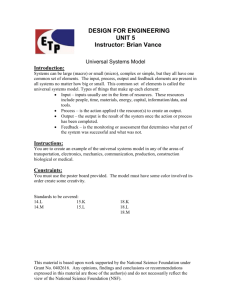

advertisement