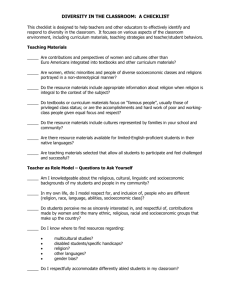

Cross-Cultural Context, Content, and Design

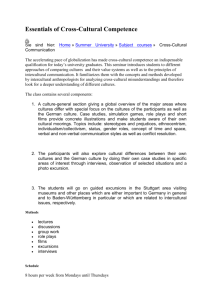

advertisement