Relationships, layoffs, and organizational

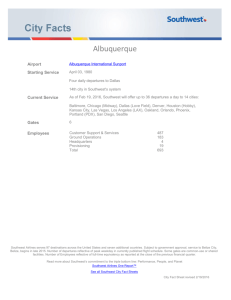

advertisement