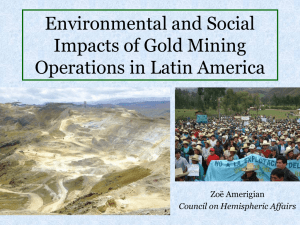

A Return to El Dorado - Center for International Conflict Resolution

advertisement