Illegal Racial Discrimination in Jury Selection

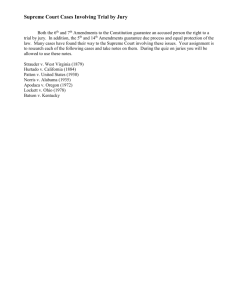

advertisement