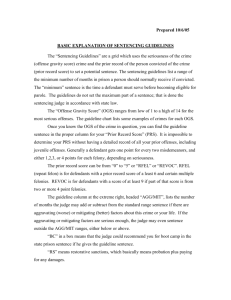

the multilevel context of criminal sentencing

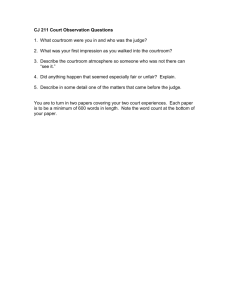

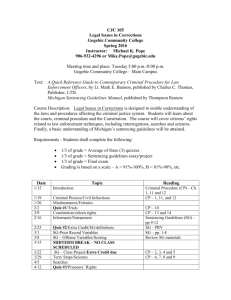

advertisement