Paper

advertisement

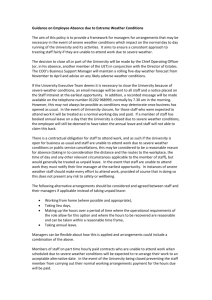

National Synergy on Information Systems Initiative, Information Gaps, and Financial Stability in Indonesia: An Institutional Arrangements Perspective1 Agung Darono2 agungdarono@depkeu.go.id Finance Education and Training Agency - Unit of Malang Ministry of Finance Republic of Indonesia Jalan Ahmad Yani Utara Nomor 200, Malang, East Java, Indonesia, 65126 Sugianto sugianto.hirokerto@bpk.go.id Bureau of Information and Communication Technology, Supreme Audit Board of Republic of Indonesia Jalan Gatot Subroto Kav. 31, Jakarta, 10210 Abstract Recently, there has been an increasing interest in financial information gaps. For instance, The International Monetary Funds (IMF) joined with the Financial Stability Board (FSB) have published a series of documents and initiatives on how global financial stability stakeholders should address these issues in 2009. Recent discussion in this area have heightened the needs to set out an appropriate mechanism in managing adequate flows of information to facilitate financial stability authorities to promote global financial stability. Each financial stability authority needs to consider a wider context in terms of providing suitable information gathering mechanism/infrastructure for current economic, social, political and technological aspects. In Indonesian context, according to the Law 11/2011 concerning Financial Service Authority (“Otoritas Jasa Keuangan”/”OJK”), stability of the financial system should be maintained through a coordination forum (called as “Forum Koordinasi Stabilitas Sistem Keuangan”/”FKSSK”) whose members consist of the Minister of Finance as coordinator and member, Governor of Bank Indonesia, Chairman of the Board of the Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Chairman of the Board of Commissioners of the OJK the members. Central to this transitional situation is in determining type of technological support as well as appropriate institutional arrangements required to establish well-designed exchange of information mechanism in the FKSSK's coordination tasks in order to maintain the financial stability. On the other side, Supreme Audit Board (“Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan”/”BPK”) as state’s auditor has recently launched its initiative, called as National Synergey on Information Systems. The main feature of this initiative is “e-Audit”, an ICT-based mechanism to capture data from BPK-auditees’ information system into BPK’s data-center. This study deploys a qualitative-interpretive method and adopts institutional arrangements and socio-technicalsystem perspectives as working tools to analyse the various relevant policies/regulation that have been enacted by the financial stability stakeholders to reduce the financial information gaps in Indonesia. The study proposes how BPK’s information systems synergy initiative (eAudit) could be considered as an information exchange infrastructure that can be utilized to support Indonesian financial stability stakeholders in reducing potential information gaps. Keywords: information gaps, financial stability, institutional arrangements 1 This article represents the personal views of the authors and does not represent any views or policies of the institutions where the authors affiliated 2 Corresponding author 1 1. Context of the Case Indonesia made a crucial step in its financial management system when the Financial Services Authority ("Otoritas Jasa Keuangan"/"OJK”) was fully operated in December 31, 2013. This authority, established based on Law No. 21/2011, is responsible for regulating and monitoring financial services activities in the banking sector, capital market, insurance, pension funds, and other financial institutions. The establishment of this entity was preceded by quite a lot of public debate regarding the choice of institutional supervision and regulation towards financial services, which was suitable in Indonesia context. The final decision is as set out in the OJK Law (Hasan, 2012; Sunarsip, 2012). According to Indaryanto (2012), Nasution (2003), and elucidations in the OJK Law, the main objectives of this authority is to serve a financial system stability, which in turn able to support sustainble national economics growth. The main tasks of OJK are to ensure fair, transparent, accountable and sustained financial services. To achieve those goals, OJK has a role as part of the Coordination Forum for Financial Stability (“Forum Komunikasi Stabilitas Sistem Keuangan”/”FKSSK”). Beside the Chairman of the OJK, this forum also includes the Minister of Finance (MoF), the Governor of Bank Indonesia (“BI”), and Chairman of the Board of Commissioners of the Deposit Insurance Agency (“LPS”) . Article 43 OJK Law, in order to achieve financial stability, explicity reign to develop and maintain an integrated information exhanges infrastructure among this forum members. Therefore, existence of financial information (and its consequences, information gaps) and how this information exchanged has been focal concern both of financial system stability authorities and scholars (Cushman, 2012; Oosterloo and Haan, 2004; Nasution, 2003; Jappelli and Pagano, 2002). Oosterloo and Haan (2004) revealed that the main point to maintain the financial stability are co-operation dan information exchange between the whole financial stability stakeholders. It means that those stakeholders have to keep their information current and update. The urgency of this issue has also been made of the finance ministers and central bank governors of the G20-countries to invite the IMF and FSB identify any information gaps int the field of economy and financial stability, and asked to immediately close the various loopholes should be closed (IMF and FSB, 2009). In relation either with the information gaps or information exchange, in the term of financial stability objectives, the situation in Indonesia has shown that these issues also have become crutial attention among of the financial system stability stakeholders. In this sense, Table 1 elucidate excerpts based on report by IMF (2010) and FSB (FSB, 2013), concerning the results of the assessment towards Indonesia’s financial system stability as well as its responses from the related authority. This table describes the specifics information related to information exchange mechanism that had been arranged among the authorities. Table 1. Assessment Results towards Information Gaps in Financial Stability Reports Facts/Criteria Authority’s Responses Financial System Stability Assessment (IMF Country Report No 10/288), 2010 “ ... the lack of formal and informal information sharing arrangements with other financial sector supervisory authorities ...” IMN Survey of National Progress in the Implementation of G20/FSB Recommendations, 2013 To quicken supervisory responsiveness to developments that have a common effect across a number of institutions, supervisory exchange of information and coordination in the “ ... It should be noted, however, that the lack of formal information sharing arrangements did not materially impede our practice of consolidated supervision, as noted in the overall assessment of consolidated supervision ...” “ ... At national level, BI has signed bilateral MoUs with other relevant financial sector authorities such as with OJK and Indonesian Deposit Insurance Corporation (LPS). Furthermore, a Financial System Stability Coordination Forum (FKSSK) that was mandated by OJK Law has also been established in 2012. The FKSSK 2 Reports Facts/Criteria development of best practice benchmarks should be improved at both national and international levels Authority’s Responses establishment was formalized through a FKSSK MoU that was signed by Minister of Finance, Governor of Bank Indonesia, Chairman of OJK’s Board of Commissioners, and Chairman of LPS’s Board of Commissioners. The MoU facilitates the sharing of information and data among authorities that are required to maintain and promote financial system stability. At international level, in the banking sector, as a response to BCP FSAP recommendations, BI has entered into formal arrangements with several foreign authorities since 2010, such as with foreign authorities such as China (CBRC), Malaysia (BNM), Singapore (MAS), Australia (APRA), and Korea ...” Source: data gathered by authors According to authorities’ responses, it seem that everything goes fine. However, in the authors' view, the real situation is more complicated than its looks like, especially with how the MoU between these members of FKSSK are followed up. Why? Because, in some cases coordination measures toward exchange of information initiatives are not always an easy one in Indonesia. Back to 2007, for instance, the stock exchange operator (then Jakarta Stocks Exchange/JSX), had deciced to introduce a new reporting mechanism based on eXtensible Business Report Language (XBRL) data format which at that time was considered as the best practice for financial information reporting, but this initiative did not not run smoothly. It was fail not due to technical issues, but referring to Williamson’s term (2000), rather on institutional arrangements issues. In fact, the constraints arose from active stocks exchange members who considered this initiative as a violation to sound business practices. That parties argued that the designated provider for development and implementation of e-reporting was appointed without going through the fair mechanism. As a result, this JSX regulation was then reported by such parties to the Commission for the Supervision of Business Competition ( “Komisi Pengawas Persaingan Usaha"/”KPPU" ), and such commission decided to cancel the JSX regulation 3. In this context of information exchanges that require some of parties to involve, and in a broader scale (not merely related to financial system stability objectives), there is a different approach that can be used to deal with this information exchanges mechanism, one which emerged from the Supreme Audit Board (“Badan Pemeriksan Keuangan”/”BPK”), namely National Synergy on Information System (“Sinergi Nasional Sistem Informasi”/”SNSI”), with “e-Audit” system-application as its core feature. According to BPK’s press release (BPK, 2012), SNSI/e-Audit initiative basically aims to facilitate electronic-information gathering by BPK’s auditors through a data communication network (i.e. internet) from the auditee computing environment. From auditing dicipline, according to (Darono, 2010), this measure known as continous auditing or embedded audit modules technique. Accordingly, this initiative is basically not directly engaged with financial system stability objectives. But, in contrary referring to Hadi Poernomo, the Head of BPK, this initiative should be expanded to a broader scope, namely to establish an information exchange infrastructure and build the national data center. As he said: 3 Source: http://bit.ly/1ctLic0 3 "... The national data center consists of two major parts, namely the public financial and private financial data. If national data center exists, monitoring could be strengthened ... "4 As of December 2013, e-Audit has covered 749 auditees consisting of 524 local governments (provincial/district) and 90 ministries/agencies, and also 177 office of state treasury (Directorate General of Treasury as part of MoF). Thus, e-Audit system-application with its configuration and specific mechanisms will retrieve data from its client either at the Database Management System (DBMS)-level or file-system level. The captured-data then transferred to the BPK’s data-center through a data communication channel (i.e. internet). Later, this data will be analysed by auditors as entry points to generate audit reports. Technically speaking, the transfer of captured-data from auditees’ network to the BPK’s data center could simply be done by installed specific software (referred to as "consolidationagents", a common terminology used in the ICT dicipline for this is daemons or services) in the auditees’ hardware (computer network). Figure 1 illustrates an e-Audit technical configuration as well as how the stream of data from the auditees’ computer network to the BPK’s computing platform and then accessed and used by the auditors. Further, are there any links between the information gaps reduction or information exchange in the term of financial stability, on one side, and SNSI/e-Audit initiated by BPK on the other side? From authors’ point of view ─ yes, there are. How JSX cancel the impmentation of XBRL-based e-reporting mechanism. Likewise, debate on how information management in the term of banking supervision should be conducted by OJK given that this new authority has not had adequate resources (i.e. human resource, hardware, software, operating procedures). Not to mention other problems OJK faced: how to supervise the capital markets or other financial service providers5. Those are potential discrepancies between the technical-technological and the institutional arrangements aspects. Meanwhile, BPK’s SNSI/e-Audit is relatively smooth to hold more than 800 entities to join their information exchange infrastructure. Hence, BPK’s approaches in this context have a enormous potential to be adopted by the financial system stability stakeholders to establish their(own) information exchange infrastructure. That is to say, all situation described above indicate the need of proper institutional arrangement in connection with how FKSSK’s managed to establish an integrated information exchange mechanism. Based on above description, the research question of this paper is to investigate how to make a proper institutional arrangements of information exchange for financial stability purposes by comparing it that of BPK’s SNSI/e-Audit initative. Furthermore, this study seeks to elaborate whether SNSI information exchange mechanism could be used as merely a benchmark model or even has its potential become part of FKSSK's information mechanism exchange. This study adpots qualitative-interpretive approach and will combine both institutional theory and socio-technical-system theory as its conceptual framework. This combination was chosen to comprehend how an implementation of the system-standard-technology (in this context is SNSI as an ICT-based information exchange mechanism) as a social artifact. Consequently, this study focuses on its institutional context. This context mainly relates with how process of designing an appropriate institutional arrangements to support systemstandards-technology in imlementing information exchange infrastructure for financial stability purposes. The reason of using the institutisonal arrangements perspective in this case is motivated by how any institutional layers can be easily identified and intertwined in a 4 Source: http://www.bpk.go.id/news/bpk-gagas-pusat-data-nasional . Translated by authors. See for example: http://www.infobanknews.com/2013/07/soal-laporan-bank-dpr-berang-bi-tawar-undangundang/ 5 4 e- AUDIT INFRASTRUCTURE Core Database Consolidator-Agent INTRANET BPK Representative Offices Database & Filesystems MAK CAMPUS LAN E-Audit Portal Secure Access INTERNET Auditors Auditors Ministries Entity’s Users AK ConsolidatorAgent ConsolidatorAgent Filesystems Database Local Governments State-Owned Enterprises Data Sources Data Sources Figure 1. BPK’s e-Audit Infrastructure (source: BPK) 5 social structure. Having said that, this research will therefore discuss what kind of institutional arrangements should be developed in this context (Ropohl, 1999; Williamson, 2000; Orlikowski and Barley, 2001; Avgerou, 2003; Eason, 2008; Eaton et al., 2008; Hassan and Gil-Garcia, 2008; Briggs and Brooks, 2011; Bunel and Lescop, 2013). This study utilised interpretive policy analysis (IPA) described by Glynos et al (2009) as data analysis method. Authors argue this method will help to delve into detail such related policy and involved-social-structure in establishment of information exchange mechanism for financial stability purposes. IPA method allows researchers to articulate well-founded interpretations of policymaking that presume the judgements and values of the researcher are involved, and not to produce objective facts or causal explanations (Walsham, 2006; Glynos et al., 2009). The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The second section presents relationship between information gaps and financial stability. Third section discusses institutional arrangements in the context of information exchange practices. Then, all discussions concluded in the fourth section. 2. Information Gaps and Financial Stability Schinasi (2007) describes the financial stability as a mechanism to prevent financial problem into a systemic thing that threatens the economic system but also must keep the economy's ability to grow and carry out its main functions. Meanwhile, FSI (2007) suggests that financial stability is a situation in which the financial system operates efficiently and is able to withstand relatively large shocks in economics and finance. According to Duisenberg, as cited by Oosterloo and Haan (2004), although there is no single definition towards financial stability term, at least there is a consensus that a stable financial system is a situation that allows all the major elements of the system to work well. Regarding this, Gunadi (2011) emphasised that public have their rights to know the condition of financial system stability and the whole economics environment. This is also a part of the the financial system authorities accountability. Communication and information is also important to increase public confidence towards stability of the existing financial system. Gunadi (2011) further said that in some cases, the prevailing condition of information exchange to support communication and information purposes still face some obstacles: “... There are also information sharing and data exchange problems among financial authorities. These conditions create additional challenges for macroprudential surveillance. Furthermore, the high possibility of undetectable potential risks and imbalances in the financial system makes the tasks even more challenging and difficult ...” Burgi-Schmelz et al (2010) reveal that one of the important learned lessons of the global financial crisis, back in 2008, was there are needs for all elements of the financial system to have sufficient information and available on timely basis, as a tool to evaluate sorts of potential instability. Furthermore Oosterloo and Haan (2004) also outlines that one of the preconditions for financial stability is to provide sufficient information as a decision making tool on each element of the financial system. This is in line with what has been emphasised by Nasution (2003) and Houben et al (2004) that one of the causes of financial instability is information asymmetry. This information asymmetry condition has an inclination to encourage the actors of such financial system (or economy in general) to take moral hazards or adverse selection action which are to some extents will trigger instability in the financial system (Crockett, 1997; Nasution, 2003; Deliarnov, 2006; Schinasi, 2007) 6 Satria et al. (2012) explicates that the global financial crisis in 2008 then led to underline the term of macroprudential and microprudensial analysis. Both of these terms actually are not two separate concepts in a discrete manner, but better be viewed as a continuum so the analysis would be intertwined between two of these things. According to Gunadi (2011) and also Deriantino (2011), information needs in macro- and micro- prudensial prudential, are slightly different. Refer to Brio in Satria et al. (2012) macropudensial analysis needs of topdown information, while micropudensial analysis is bottom-up information. Gunadi (2011) employed two diffrent terms to distinguish this analysis: macroprudential-surveillance and microprudential-supervision. Both of these terms are categorical in nature, to distinguish the level and purpose of each type of analysis. The consequence of this difference is the different data resources to be used for analysis. For macroprudential surveillance purposes, required data are more related to the detection and identification of potential vulnerabilities and risks associated with the financial markets, financial institutions, or the structure of the overall economy. Meanwhile, int the microprudensial analytical side are more likely to use the data obtained from systems such as Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS), Debtor Information System (“Sistem Informasi Debitor”), or government liquidity monitoring system (“BIG-eB” system) (BI, 2008; Gunadi, 2011; Deriantino, 2011). Up to this point, the authors concluded that the information is necessary in achieving financial stability, but at the same time there are also information gaps. How to reduce or eliminate the gaps? Research by Murphy and Westwood (2010) suggest that the British government should invite various stakeholders (including the Bank of England) to reorganize how institutional arrangements should be appropriately established in the process of collecting a variety of information management in the context of financial stability. Information gaps can occur even on information that is essential to make the party that should be enough information users need to find yourself a such information. Sulistiowaty and Nopianti (2010), for example, illustrate that BI should do: “... more progressive statistics data and information than that issued by official institutions. Since the official economics data are not available to be used as supporting data immediately, BI conducts some surveys on a regular or ad hoc basis as a source of supplementary information on macro or micro economic conditions to obtain early indicators respecting national economic movements earlier than official data ...” This constellation seems to push IMF and FSB (2010) to state that: “ ... Closing all the gaps will take time and resources, and will require coordination at the international level and across disciplines, as well as strong high-level support. The legal framework for data collection might need to be strengthened in some economies ...” To cope with these information gaps issues, IMF and FSB (2013) explore the possibilities of an increased connectedness between various financial organizations, including among supervisory agencies. This measure obviously must consider the legal issues and data confidentiality as well as institutional arrangements between involved institutions, including the supervisory agencies. The question then arises is how to develop an information exchange mechanism in accordance with the various conditions (technology, organisation structure, legal aspetcs) in each component of the financial system? Based on above described facts as well as previous research results, the answer to this question can be seen from two sides, the practical-operational technology and institutional arrangements. The practical aspect of information exchange would involve various stakeholders, either as the senders or receivers of exchanged information. At this time, mostly all of the information exchange mechanism takes place with the use of information and communication technology (ICT) supports. Hence, the information exchange in this case is not merely seen as a matter of technology alone, but must also be seen from the institutional-organizational perspectives (Ropohl, 1999; Kling, 1999; Orlikowski and Barley, 2001; Avgerou, 2003; Briggs and Brooks, 2011). 7 3. Institutional Arrangements in Information Exchange Practices In economics the concept of institutions, Williamson (2000) as also cited by Bunel and Lescop (2013) revealed the presence of four levels of institutions, namely: (1) an informal institution, such as moral values, local customs; (2) institutional environment, such as: legal, formal political organizations; (3) institutional arrangements, such as: the relationship between institutional governance; (4) resource allocation, price, insetives-disincentives, are dynamic and change over time, such as: the behavior of the agents, margin and pricing, allocation of resources. Somewhat different, Fountain (2001) defines institutional arrangements as laws, regulations, and other cultural cognitive, or socio-structural constraints found in governance contexts. Meanwhile, Yustika (2010), identified the term institutional environment and institutional arrangements. Macro-approach (institutional environment) is an enabling environment, concentrating on the preparation of the legal framework, economic, and political policies that produced that can answer your targeted goals. At the micro level (institutional arrangements), this approach will design specific rules of games to allow all economic actors to compete or collaborate in a fair way. Based on some notions regarding the institutional arrangements, this paper will elaborate the possibility of institutional arrangements that may be exist in the context of the relationship between the information exchange for financial stability purposes and SNSI initiative as an alternative-infrastructure information exchange. Hassan and Gil-Garcia (2008) suggest that institutional arrangements are important elements for understanding how information technologies (including information exchange) are selected, designed, implemented, and used in public organizations. Some researchers have used the concept of institutional arrangements as an analytical tool for examining the application of the technology (i.e. ICT) as part of the particular public policy (administration). Bunel and Lescop (2013), use institutional arrangements analysis framework to describe how specifics ICT-application policy is designed and implemented. Whereas Brigss and Brooks (2011) describe how the institutional arrangements play an important role in the implementation of electronic (internet based) payment systems. Nejman et al., (Nejman et al., 2010) in the context of the situation in Czech Republic, reveal the importance of appropriate institutional arrangements to each different environment so that the collection of data and statistics from the financial markets. Adequate institutional arrangements needed to ensure data qualitaty, to reduce the workload on the each unit which have an exchange information obligation, and to streamline the whole needed resources. In the Indonesian context, from sectoral perspective, various authorities/organizations in the field of private or public financial management had their experiences in term of how to set up an appropriate institutional arrangements which involved an ICT-based application systems. A recent study by Darono (2013) outlined how institutional arrangements affect the implementation aspects of data exchange in the field of tax administration application, electronic tax payments, and electronic tax filing. Also, an official report published by BI (2012), explained how the institutional arrangement capable of pushing interconnection (which is basically an information exchange mechanism) between BCA and Bank Mandiri as the two largest payment provider in Indonesia became available. Consequently, this measure in turn have made national payment network become wider. Table 2 displays some institutional arrangements related to financial information exchange initiatives (electronically/ICT-based) among different entities as information providers. 8 Table 2. Information Exchange Applications for Financial Information Information Exchange Involved Entities Purposes Applications as Institutions State Revenues Module (“Modul Penerimaan Negara”/ “MPN”) Bank Indonesia-Real Time Gross Settlements (BI-RTGS) Indonesia National Single Window (INSW) BIG-eB State Revenue Authority, State Treasurer, Banking Insitutions Jakarta Auto mated Trading Systems (JATS) Stock Exchange Authority, Broker, Investor, Clearings & Settlements Authority Initiated by Bank Indonesia, especially “to force” integration between BCA and Bank Mandiri as two major payment providers National Payment Gateway Bank Indonesia, Banking Insitutions Customs Authority, Ports Authority, Banking Insitutions Ministry of Finance, Bank Indonesia, Banking Insitutions Information exchange for tax state revenues (taxes, import’s duties, excises, etc.) Information exchange for interbanks transation Information exchange for import/export transaction Information exchange for government fund transfer and liquidity Information exchange for all financial-products traded at Indonesia Stocks Exchange Information exchange for payment or other financial transaction, Source: data gathered by authors Referring to the cancellation of the implementation of XBRL-based e-reporting for listed companies, this indicated problems need to be addressed in relation to the institutional arrangement for the financial information exchange. If listed-companies along with capital market operators are still reluctant to apply information exchange mechanism with international data standards, therefore the implementation process among financial services companies, given that they have lower qualification or scale , is questionable. To overcome this condition, in authors view, it is neccesary for financial stability stakeholders try to take different perspectives. In the context of either existing technical-technological or institutional arrangements, it is better for financial stability to pay more attentions on what has been achieved by the BPK with its SNSI/e-Audit. This initiative can be viewed as an alternative mechanism for the stakeholders of financial stability. In our deeper analyses, this e-Audit system-application has developed its information gathering structure (not yet for information exchange, because in its nature this application only captured information from auditee in a one-way direction) with various parties (auditee and some other informasi sources, such as airline company) in a simple data communication setting, involving a huge amount of data, and using reliable data transfer performance. There are some arguments to consider both technical aspects and institutional arrangement of e-Audit mechanism an alternative information exchange infrastructure in terms of financial stability purposes, namely: (1) data source in remote sites can be either a database/DBMS (as long as featured with Java Database Connectivity/JDBC) or file systems (e.g. Microsoft Excel file); (2) internet-based communications network, without specifics/dedicated data communication network (such as leased-line); (3) RSA-standard’s encrypted data; (4) maintenance-free application, particularly for remote sites, since all patches/softwareupdates/configuration are performed by BPK’s technical staffs. Having said that, this configuration actually accords with the requirements of the desired information exchange mechanism as explicitly stated in OJK Law which affirmed in Explanation of Article 43: “... principally OJK shall build, maintain and develop the integrated information system in accordance with the duties and authorities. What is meant by "integrated" is that a system built by the OJK, Bank Indonesia, and the Deposit Insurance Corporation are connected to each other, so that each institution can exchange information and to access banking information required at any time (timely basis). This information covers general and specific information about the bank, the bank's financial statements, bank 9 examination report conducted by Bank Indonesia, the Deposit Insurance Corporation or by OJK, and other information while maintaining confidentiality and consider the information in accordance with the provisions of the legislation .. . “6 Daeng M. Nazier, Deputy of the Head of BPK in Planning and Development, explained that the e-audit as a service application is still being developed and is expected to fully operated in 2014 (BPK, 2011). BPK’s Warta BPK (2011) revealed that: “ ... The foundation built by incorporating the implementation of e - audit in BPK Strategic Plan 2011-201. Furthermore, an important part of the BPK Strategic Plan Implementation Plan. And, are automatically included in the plan BPK Bureaucracy Reform. To that end, in order to become stronger foundation, BPK perform some steps into the corridor bureaucratic reforms to strengthen the implementation of e-audit. The steps are performed that includes the arrangement of legislation, governance, organizational management, human resource management. After the stage of development of this foundation has an early form, performed the test phase application through pilot project. In consideration of the readiness of the parties or the examined BPK’s auditee, CPC participation in the labor force, and the readiness of the CPC inspectors in carrying out this e-audit. Readiness associated with the auditee, the CPC took them through the signing of a memorandum of understanding on the development of information systems for data access . BPK still going to do it again until all the auditee to sign MoU ... " Some critics raise towards the implementation of e-Audit, both againts its performance, data privacy and institutional arrangments over the e-Audit itself. Praseno (2012) emphasised that from the perspective of the auditors and auditing dicipline, e-Audit: (1) just another way to digitize documents; (2) tend to focus data collection without further elaborating the internal audit capacity of each auditee. Over this situation, this study not only see the effectiveness of e-Audit through the whole (government’s financial statement) audit process, but more on function of this effort as a mechanism for collecting (financial) information. This point of view is needed to improve (financial) information collection infrastructure in Indonesia. So, what kind of institutional arrangements are appropriate to support the information exchange for financial stability purposes in Indonesia? This paper does not attempt to give a final answer, but more on thrusting an alternative institutional arrangements which, if desired, can be discussed further at the operational levels, among the members of FKSSK. As mentioned earlier, the information exchange in the current era should be read as ICTbased information exchange. Therefore, further discussion on the choice of the proposed institutional arrangements are influenced by a variety of concepts , experiences or practices which involve the use of ICT in various forms and levels. Based on the various policies that have been there for this and the fact findings of the study, this paper with reference to Williamson (Williamson, 2000) and Bunel and Lescop (2013), put forward a perspective of institutional arrangements for data exchange as part of the financial stability purposes, as illustrated in Figure 2. 6 Translated by authors 10 Embeddedness: informal; customs, traditions, norms, religion Financial stability to achieve sustainable economic growth Institutional environment: formal rules of he games t esp. - (property (polity, 1st order judiciary, economizing bureaucracy Financial institution, bank stock exchange (i,e: BI Law, OJK Law, LPS Law, Public Finance Law) Governance : play of the game esp. contract , governance 2nd order judiciary, aligning structures transactions Resource allocation and employment: prices and quantities, incentive alignment MoU BI-OJK-LPS-MoF RTGS, DIS, Listed Companies’ e-Reporting, National Payment Gateway BPK’s SNSI initiative (National Data Center, e-Audit) BPK-Auditee MoU, data privacy, information exchange protocols, service level agreements Figure 2. BPK’s e-Audit as an Alternative Information Exchange Infrastructure for Financial Stability and its (proposed) Institutional Arrangements (adapted from Williamson (2000) and Bunel and Lescop (2013) ) Referring to the response of the members of FKSSK on the results of the assessment of financial stability by IMF (2010) and FSB (FSB, 2013) concerning how they exchanged information between them, have explained that there was a change in the way they exchange information. They decided to establish MoU among each member of FKSSK. The problem is, as far authors known, this agreement has not become an institutional arrangement as Williamson (2000) emphasised. In this concept, institution at the level of 3-4 (see Figure 2), should form an operational framework as a means to an end. In this case, namely information exchange as ruled by institutions at level 2 (i.e. Article 43 OJK Law). In this constellation, SNSI/e-Audit is gaining its momentum to be seen as an alternative information exchange infrastructure, especially for the financial stability purposes. It is actually also in line with the earlier idea of SNSI initiative as way to eastablish the national data center. Furthermore, why SNSI/e-Audit is chosen as an alternative? Because, this system-application supported by relatively more appropriate institutional arrangements. In authors perspective, e-Audit as institution at level 3, is already supported by information exchange MoU between the BPK as auditor (information user) and auditees as data owner, one which includes the matters related to information privacy and confidentiality issues. Finally, at level 4, it can be found that e-Audit already has its: (1) standard data exchange with appropriate mechanisms in term of using relational database or file system as data sources; (2) procedures for accessing or utilizing the data. All of this propositions reveal that e-Audit relatively has proper institutional arrangements. 11 4. Conclusion This study found that information gathering mechanisms/infrastructures have been developed by the BPK through its e-Audit approach (as a part of BPK’s SNSI initiative), to some extents, should be viewed as an alternative information gathering/exchange mechanisms which can be used by financial stability management stakeholders to reduce the information gaps and in turn support the exchange of information to carry out the FKSSK’s coordination function. In the context of institutional arrangment in Indonesia, the authors found that the advantages of using a data consolidation mechanism through e-Audit are: (1) BPK has the authority to request data to many agencies, based on the BPK's authority legal position as state auditor; (2) BPK has developed an ICT-based information gathering that satisfies the institutional arrangements in terms of public finance system in Indonesia. It means that to some extents the FKSSK’s information exchange mechanism better to consider of using BPK’s e-Audit infrastructure; (3) Especially related to the OJK’s function, technically speaking, e-Audit’s technology and model of information gathering can be implemented to capture data from many types of non-bank financial institutions since from technological perspective such institutions still have not sufficient information management capacity to provide reports by using an application or data standardization approach. There are things should be explored further with regard to the position of BPK in this institutional arrangment. This circumstance seems to pose BPK (as state auditor) become a part of day-to-day public finance management. BPK possesses the authority to conduct examination of financial management, so it might just be a potential debate on why the supervisory authorities are also be involved in the management process. In the authors’ view, that opinion may arise, but also will easily be broken with a broader interpretation of the definition of what the financial supervision is. It can also be assumed that the implementation of e-Audit is a continuous online auditing techniques. Thus, by using the institutional arrangements perpective, the authors concluded that the use of BPK’s e-Audit as data consolidation mechanism with the aim of reducing the financial information gaps and supports coordination functions for the benefit of financial stability, remains feasible to be implemented. The consequence of this choice is how to establish a legal framework as a form of governance concerning the use of collected information in BPK’s data center. This should be emphasised, because the nature of the information gathering through e-Audit scheme (or SNSI inititative) are for financial audit purposes conducted by BPK. Therefore, the use of collected data outside of initial purposes such as data for supporting information exchange mechanism for coordination functions of FKSSK to achieve stability of financial system requires adequate more formal legal frameworks. Acknowledgment Authors would like to thank to the commitee of conference for providing financial assistance to attend the conference, Dr. Rochmadi Saptogiri (Head of IT Bureau, Supreme Audit Board), Mr. Agus Hermanto (Secretary of Finance Education and Training Agency, Ministry of Finance) and his staffs for providing administrative supports, and Mr. Arifin Rosid (University of New South Wales, Sydney) for helps and comments. 12 References Avgerou, C., 2003. New socio-technical perspectives of IS innovation in organizations in: Avgerou, C., Rovere, R.L.L. (Eds.), Information systems and the economics of innovation. : Edward Elgar. BI, 2008. Laporan Sistem Pembayaran dan Pengedaran Uang. Direktorat Akunting dan Sistem Pembayaran & Direktorat Pengedaran Uang - Bank Indonesia (BI), Jakarta. BPK, 2011. Menuju E-audit yang Paripurna, Warta BPK. Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan. BPK, 2012, Siaran Pers BPK: BPK RI Resmikan Gedung Balai Diklat dan Sepakati Cara Mengakses Data dengan Pemerintah Daerah se-Provinsi Sumatera Utara. URL.http://www.bpk.go.id/web/files/2012/07/SIARAN-PERS-MOU-AKSES-DATAPROV.-SUMATERA-UTARA.pdf Briggs, A., Brooks, L., 2011, Electronic Payment Systems Development in A Developing Country: The Role of Institutional Arrangements. The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries 49(3), 1-16. URL.https://www.ejisdc.org/ojs2.../index.php/ejisdc/article/view/860/381 Bunel, A., Lescop, D., 2013, A new institutional perspective on shared spectrum access issues. 24th European Regional Conference of the International Telecommunication Society. Burgi-Schmelz, A., Leone, A., Heath, R., Kitili, A., 2010, Enhancing information on financial stability. Initiatives to address data gaps revealed by the financial crisis. Crockett, A., 1997, Why is Financial Stability a Goal of Public Policy? Economic Review Q IV, pages 5-22. URL.http://econpapers.repec.org/article/fipfedker/y_3a1997_3ai_3aqiv_3ap_3a522_3an_3av.82no.4.htm Cushman, B., 2012, Institutional Arrangements in Promoting Financial Stability: U.S. Experience. International Seminar On Financial Stability: Financial Stability Through Effective Crisis Management And Inter-Agency Coordination. Darono, A., 2010, Teknik Audit Berbantuan Komputer: Menelaah Kembali Kedudukan dan Perannya. Seminar Sistem Informasi Indonesia Deliarnov, 2006, Ekonomi Politik. Erlangga. Deriantino, E., 2011. Addressing Risks In Promoting Financial Stability: Indonesia Experience, in: Gunadi, I. (Ed.), Addressing Risks in Promoting Financial Stability. Published by The South East Asian Central Banks (SEACEN) Research and Training Centre. Eason, K., 2008. Sociotechnical systems theory in the 21st Century: another half-filled glass?, in: Graves, D. (Ed.), Sense in Social Science: A collection of essays in honour of Dr. Lisl Klein, Broughton. Eaton, D., Meijerink, G., Bijman, J., 2008. Understanding Institutional Arrangements Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Value Chains in East Africa, Markets, Chains and Sustainable Development Strategy & Policy paper. Stichting DLO, Wageningen. FSB, 2013. 2013 IMN Survey of National Progress in the Implementation of G20/FSB Recommendations. Financial Stability Board (FSB), Basel, Switzerland. Glynos, J., Howarth, D., Norval, A., Speed, E., 2009. Discourse Analysis: Varieties and Methods. National Centre for Research Methods - Centre for Theoretical Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences - University of Essex. 13 Gunadi, I., 2011. Addressing Risks In Promoting Financial System Stability In SEACEN Economies: A Survey, in: Gunadi, I. (Ed.), Addressing Risks in Promoting Financial Stability. Published by The South East Asian Central Banks (SEACEN) Research and Training Centre. Hasan, H., 2012, Efektivitas Pengawasan Otoritas Jasa Keuangan terhadap Lembaga Perbankan Syariah. Jurnal Legislasi Indonesia 9(3), 373-394 Hassan, S., Gil-Garcia, J.R., 2008. Institutional Theory and E-Government Research, in: Garson, G.D., Khosrow-Pour, M. (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Public Information Technology Volume I. Information Science Reference (an imprint of IGI Global). Houben, A., Kakes, J., Schinasi, G., 2004. Towards a framework for financial stability, Occasional Studies. De Nederlandsche Bank, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. IMF, 2010. Indonesia: Financial System Stability Assessment (IMF Country Report No 10/288). International Monetary Fund Washington, D.C. IMF, FSB, 2010. The Financial Crisis and Information Gaps: Progress Report Action Plans and Timetables International Monetary Fund Publication & Financial Stability Board. IMF, FSB, 2013. The Financial Crisis and Information Gaps: Fourth Progress Report on the Implementation of the G-20 Data Gaps Initiative. International Monetary Fund Publication & Financial Stability Board. Indaryanto, W., 2012, Pembentukan Dan Kewenangan Otoritas Jasa Keuangan. Jurnal Legislasi Indonesia 9(3), 333 - 342 Jappelli, T., Pagano, M., 2002, Information sharing, lending and defaults: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance 26 (2002) 2017–2045 26, 2017-2045 Kling, R., 1999, What is Social Informatics and Why Does it Matter? D-Lib Magazine 5(1). URL.http://www.dlib.org/dlib/january99/kling/01kling.html Murphy, G., Westwood, R., 2010, Data gaps in the UK financial sector: some lessons learned from the recent crisis. Initiatives to address data gaps revealed by the financial crisis. Nasution, A., 2003, Masalah-Masalah Sistem Keuangan dan Perbankan Indonesia. Seminar Pembangunan Hukum Nasional VIII yang diselenggarakan oleh B. Nejman, M., Cejnar, O., Slovik, P., 2010, Improving the quality and flexibility of data collection from financial institutions Initiatives to address data gaps revealed by the financial crisis. Oosterloo, S., Haan, J.d., 2004, Central Banks and Financial Stability: A Survey. Journal of Financial Stability 1, 257–273. URL.http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.ugm.ac.id/science/article/pii/S157230890 4000221 Orlikowski, W.J., Barley, S.R., 2001, Technology and Institutions: What can Research on Information Technology and Research on Organizations Learn from Each Other? . MIS Quarterly 25(2), 145-165 Ropohl, G., 1999, Philosophy of Socio-Technical Systems Society for Philosophy and Technology 4(3). URL.http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/SPT/v4_n3html/ROPOHL.html Satria, R., Driawati, I., Indrajaya, Febriarti, P., 2012. Macroprudential and Microprudential Surveillance and Policies, Financial Stability Review. Bank Indonesia, Jakarta. Schinasi, G.J., 2007, Understanding Financial Stability: Towards a Practical Framework. IMF Seminar – Law And Financial Stability 14 Sulistiowaty, H., Nopianti, A., 2010, The usage of surveys to overrun data gaps: Bank Indonesia’s experience Initiatives to address data gaps revealed by the financial crisis. Sunarsip, 2012, Mewujudkan Otoritas Jasa Keuangan yang Efektif. URL.http://economy.okezone.com/read/2012/02/21/279/579417/large Walsham, G., 2006, Doing interpretive research. European Journal of Information Systems (2006) 15, 320–330 15, 320-330 Williamson, O.E., 2000, The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead. Journal of Economic Literature 38(3), 595-613. URL.http://www.jstor.org/stable/2565421 15