"No God in Common:" American Evangelical Discourse on Islam

advertisement

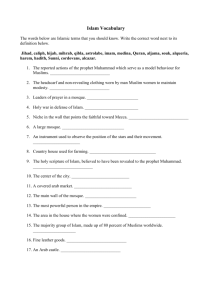

Religious Research Association, Inc. "No God in Common:" American Evangelical Discourse on Islam after 9/11 Author(s): Richard Cimino Reviewed work(s): Source: Review of Religious Research, Vol. 47, No. 2 (Dec., 2005), pp. 162-174 Published by: Religious Research Association, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3512048 . Accessed: 28/10/2012 22:59 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. . Religious Research Association, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Review of Religious Research. http://www.jstor.org "NO GOD IN COMMON:" AMERICAN EVANGELICAL DISCOURSE ON ISLAM AFTER 9/11 RICHARDCIMINO NEWSCHOOLFOR SOCIALRESEARCH REVIEWOF RELIGIOUSRESEARCH2005, VOLUME47:2, PAGES 162-174 After the September11 terroristattackson the U.S., evangelical leaders emergedas strongcritics and even antagonistsof Islam. This rhetoricis reflectedin evangelical books and articles thathave beenpublishedin the last decade, butparticularlysince 9/11. Througha contentanalysis of evangelical bookson Islampublishedbeforeand after 9/11, this articlefinds that therewas a noticeable change of emphasisandperspective on Islam after the attacks. Most of the post-9/11 literaturedraws sharper boundariesbetween Islam and Christianityand asserts that Islam is an essentially violent religion. Thispolemic against Islam takes threeforms: apologetics to prove the truthof Christianityagainst Islam;propheticliteraturelinkingIslam as the main protagonist in end-timesscenarios; and charismatic literatureapplying "spiritual warfare" teachings to Islam. Thearticle concludes that the greaterand morevisible pluralismin Americansociety is challengingevangelical identity,leading to the erection of new boundarymarkersbetweenevangelicalismand otherreligions.Suchnew boundariescan strain interfaithrelations,yet they also function to strengthenevangelical Protestantidentityin the U.S. INTRODUCTION ihile the numberof Muslims in the U.S. is in dispute,their very presence in the U.S., like the earlierpresenceof Jews, challengesolderestablishmentsand ways of doing things.A Diversity Survey conductedby RobertWuthnowfound that 48% of the public claimed to have had at least some personalcontact with Muslims, and eight percenthave attendeda Muslim mosque.Wuthnownoted that these figures are considerablylargerthan the percentagesof Americans in the 1970s who experimentedwith Easternnew religions. "Inshort,thereis a kind of culturalawareness,undoubtedlyforged as much by television and motion picturesand by internationaltraveland culturalmixing as by recent trendsin immigration,which far exceeds and transcendsthe actualnumbers of Muslim,Hindu,or Buddhistadherents"(Wuthnow2003). A growingsymbolicinfluence of Muslims in Americansociety could be seen in the appointmentof a Muslim chaplainto the Senate and even in the fact that a Muslim led the benediction duringthe Republican Conventionin 2000. But it took September11, 2001 (referredto throughoutthis articleas 9/11) to bringthese changes home to many otherAmericansand to evangelicalsin particular.In the years following the terroristattacks,evangelicalProtestantshave shownthemselvesto be amongthe W 162 No God in Common most caustic critics and antagonistsof Islam in the U.S. In 2002, evangelistFranklinGraham called Islam a "verywicked and evil religion,"while Pat Robertsonand JerryFalwell criticized Islam as essentially violent and sympatheticto terrorism.In a similar manner, SouthernBaptistleaderJerryVines createdheadlinesby preachingthatMohammedwas a "demon-possessedpedophile"(Plowman2002). These commentswere ridiculedand criticized by more liberalChristiansand otherreligious and political leaders.The Bush administrationon severaloccasionsdistanceditself fromthese anti-Islamicstatements,maintaining its public stancethatIslam is a religion of peace. But the publicstatementsrevealeda patternof anti-Islamicpolemicsthatis foundin much of the literatureof evangelicalsandcharismaticChristiansin the periodafter9/11. This article examinesthe recentanti-Islamicpolemics in the light of the evangelicals'encounterwith the new pluralismthathas developedwithinAmericansociety duringthe pastdecade.I also attemptto relatethese polemics to evangelicalstatementsand writingsaboutsyncretismand relativismthat have appearedsince 9/11. These concerns have led evangelicalsto reassert and sharpenthe differencesbetween the teachingsof Christianityand Islam. Thereis considerabledisagreementin the sociological literatureas to the effects of interreligious conflict and pluralismamongevangelicals.Hunter(1987) arguesthatthe conflict associatedwith religiousandculturalpluralismerodesevangelicalidentity,leadingeitherto an isolationist stance or to a gradualbargainingaway of essential teachingsand practices. In contrast,Smith (1998:115) assertsthat "conflictwith ideological and subculturalcompetitorsthatreligious groups may confrontin a pluralisticsociety . . . can strengthenreligious beliefs andpractices."The presentarticleis not so muchaboutactualconflictsbetween evangelicalsand Muslims as abouthow Americanevangelicalsare reassertingtheirdifferences with Islam as a way of battlingwhatthey see as the more pervasiveculturalforces of relativismand syncretism.In such a conflictwith moder Americansociety,I arguethatsuch anti-Islamicpolemicsfunctionto strengthenthe subculturalidentityof evangelicals.Throughout this article,I use the term "evangelical"in the broadsense to include both non-charismatic and charismaticconservativeProtestantswho adhereto the threebasic tenets of this movement:stressinga personalrelationshipwith Christ,the authorityandinspirationof the Bible, and the importanceof evangelizingothers(Marsden,1991). When specificallyreferring to charismaticsand fundamentalists,I will use those terms. Recent surveyshave foundthatAmericanevangelicalsare more likely thanotherAmericans to be opposed to Islam and to believe thereis little common groundbetween the two faiths. In a Pew Surveyshortlyafter9/11, 62% of evangelicalssaid they believed theirreligion to be very differentfrom Islam,as comparedto 44% of non-evangelicalswho held this view (Pew 2001). A Beliefnet/Ethicsand Public Policy survey in 2003 found that 77% of evangelicalleadershad an overall unfavorableview of Islam. Seventy percentalso agreed thatIslam is a "religionof violence."Yet 93% said it was either"veryimportant"(52%) or "of some importance"(41%)to "welcomeMuslims into the Americancommunity."Seventy nine percentsaidit was veryimportantto "protectthe rightsof Muslims"(Beliefnet,EPPC 2003). This seeming contradictionbetween condemningIslam while acceptingMuslims in the U.S. suggests that much of the anti-Islamicrhetoricis based on issues of religion and valuesratherthanon racialandethnicprejudice.Anotherstudyby Pew in Julyof 2003 found that most Americanscontinueto rate Muslim-Americansfavorably,thoughthe percentage is inchingdownward.A decliningnumberof Americanssay thattheirown religionhas a lot in commonwith Islam:22%in 2003, comparedwith 27%in 2002 and 31%shortlyafterthe 163 Reviewof Religious Research terroristattacksin the fall of 2001. White evangelicalChristiansandpoliticalconservatives hold more negativeviews of Muslims and are more likely thanotherAmericansto say that Islam encouragesviolence among its followers (Pew 2003, IslamOnline2004). The DiversitySurveyconductedin 2003 found that47% of respondentsagreedthatthe word"fanatical"appliedto the religionof Islam,and40% said the word"violent"described the religion.Nearlyone quarter(23%)said they favoredmakingit illegal for Muslimgroups to meet in the U.S. for worship(Wuthnow2003). Aside fromsurveyresearch,however,there has been little qualitativeresearchabout evangelical attitudeson Islam. A recent content analysis (Hoover2004) of the two primaryevangelicalmagazines,ChristianityTodayand the newsweekly World,does reveal the growthof anti-Islamicattitudesafter9/11, at least among a segmentof evangelicals.ChristianityTodaymagazine,representingmore moderate or "mainstream"evangelicals, was found to downplay the idea of inevitable conflict betweenIslam and the West in its coveragein the two years after9/11. Articles aboutevangelizing Muslims and religiouspersecutionof missionarieswere the most prominentkinds of articlesin the magazineduringthis period.In contrast,World,whichmoreclosely reflects the positions of the ChristianRight, adopteda harderline, stressing the violent natureof much of Islam and criticizingnews coveragethatthe magazineviewed as favorablybiased towardthe religion (Hoover2004). The presentarticlefinds thatthe evangelicalstancetowardIslam is even more complex and diverse.I divide the evangelicalpositions on Islam, as reflectedin theirliterature,into four categories:apologetic,prophetic,charismatic-spiritual warfare,and contextualist. METHOD In this article,evangelicalanti-Islamicdiscourseis examinedthrougha contentanalysis of popularevangelicalliteraturefromthe ten yearperiodbefore September11, 2001, andin the threeyears following thatevent. The 10-yearspan priorto 9/11 was chosen in orderto have a large enough sample to analyze (therewere very few evangelicalbooks writtenon Islambefore 2001). The impactof 9/11 on evangelicalattitudeson Islamis most evidentin the apologeticbooks;the anti-Islamicthemesin the propheticandcharismaticliteraturehad alreadyemerged a decade earlier,althoughpopularizedand intensified after the terrorist attacks. The books selected for analysisin this studywere takenfrom the online listings and catalog of the FamilyChristianBookstores,one of the largestevangelicalChristianbookstore chainsin the U.S. An attemptwas made to collect all of the evangelicalbooks on Islamthat have been publishedanddistributedto these bookstores.FamilyChristianBookstorestends to exclude scholarlyevangelical publishersand books, althoughI located several of such titles and have includedthem in the analysis and comparisons.This articlethus analyzesa total of 18 books, 13 of which were writtenor reissuedafter9/11. Accordingto criteriadiscussed at the beginningof this article,each book was analyzedfor its discourseon the nature of Islam (which is relatedto the questionof whetherthe religionis inherentlyviolent), and for its explanationof the relationshipof Islamto ChristianityandJudaism(which is related to the questionof whetherMuslimsworshipthe same God as Jews and Christians). In additionto these issues, the propheticandthe spiritualwarfare-charismatic books were more the role of Islam in the times and the end criteria, analyzed using specific including in of warfare" the of Islam. of the cona content concept "spiritual critique Finally, analysis 164 No God in Common servativeevangelicalnewsweekly Worldwas conductedbetween the years of 1996-2002 to explorethe contextof anti-Islamicdiscourseandhow it is relatedto concernsover interfaith involvementand pluralism. EVANGELICAL APOLOGETIC LITERATURE ON ISLAM BEFORE AND AFTER 9/11 Withinthe evangelicalapologeticmovementone finds a distinctivelyanti-Islamicthrust. The idea that evangelical Christianitycan be reasonablydefendedagainstcritics and rival philosophiesor worldviewshas long been a stapleof the movement,with hundredsof books comparingChristianitywith rivalthoughtsystems- from Mormonismto the New Age - to show where they are in error.Until the late 1980s and early 1990s, the literatureon Islam was very sparseand those books thatdid treatthe religion includedlittle on the new Islamic resurgenceexpressedin the rise of the AyatollahKhomeini. Since apologeticbooks are usually aimed at the ordinarylayperson in their everydayencounterswith those of other faiths, the need for this literaturewas not especially pressing priorto Islam's greatervisibility and growthin the 1990s. One of the most popularof these apologetic books was Answering Islam by Norman GeislerandAbdul Saleeb (1993). The book is still used by manyevangelicalseminariesand colleges in theirapologeticscourses,thoughthe morerecentanti-Islamapologistshave criticized it. The book is a straightforward polemic againstIslam, distinguishingIslamic from Christiandoctrine.Islam's disavowalof the Trinity,the incarnationof Christ,andthe sufficiency of the Bible as God's word,as well as its teachingson the importanceof performing good works in attainingsalvationare all critiquedfrom a standardevangelicalperspective. Althoughwrittenwell afterthe growthof Islamic fundamentalismandthe religion'sgeneral resurgencein much of the world,thereis surprisinglylittle involvingterrorism,violence, jihador Islamicmilitancyin general.Most importantlyfor the purposesof this article,Geisler and Saleeb statethatthe God thatMuslims addressand worshipas "Allah"is the same God of the Old andNew TestamentsthatJews andChristiansinvoke.Of course,the authorshold thatthe Islamic view of God as taughtin the Quar'anis seriously distortedand marredby non-biblicalsources,but they do give, if grudgingly,a place to Muslims in the monotheistic family of Jews and Christians.This is not to say thatall otherpre-9/11 apologeticliterature takes a moderate approachtowardIslam. One of the books that foreshadows many elementsof the morerecentpost-9/11 literatureis IslamRevealed(1988) by Anis Shorrosh. But while this book sees armedJihadand violence as centralto Islam, it also views Muslims as fellow monotheistsalong with Christiansand Jews, a view thatstandsin contrastto the post-9/11 literature. It shouldalso be notedthatthose with a morefundamentalist orientation(forwhom apoloin assume a more central role their have faith) getics long expressed negative views concerningIslam.Apologists such as Dave Hunt and RobertMorey virulentlyattackIslam on theirweb sites, with the latterusing the imageryand languageof the Crusadesto battlethe Islamic threat(Hunt2003; Morey 2003). Popularradio broadcasterand prophecyteacher JohnAnkenberg'sbookletTheFacts On Islam (1991) is a fiery expose of the religion,touching on the familiarnerve points of Islam's essential violence and evil nature.It is not only fundamentalistsand evangelicalsthat hold anti-Islamicviews: fairly similarpositions can be found in the conservativewings of RomanCatholicismandEasternOrthodoxy(Spencer 2002, Trifkovic2002). 165 Reviewof Religious Research The books and articlesthat were published- or re-issued- after September11 sharea numberof similarcharacteristics.Like the Shorroshbook, they areoften writtenby ex-Muslims who convertedto Christianity(usuallyaftera periodof living in the West).The books are usually publicized as revealing the "real truth"about Islam that has been hidden or obscuredby the media and otherelite segmentsof Americansociety. But the two principal themesthatdistinguishthese books from thatof the pre-9/11 literatureis the dual emphasis on Islam'sinherentlyviolent nature,a fact revealedby the September11 attacks,and, most importantly,the assertionthatMuslimsworshipa false god distinctlydifferentthanthe God of ChristianityandJudaism.One of the mostpopularof these books is UnveilingIslam,written by ex-MuslimsErg and EmirCaner(2002), which was the sourceVines cited when he made the remarkaboutMuhammad.The book is reportedto have sold over 100,000 copies and seeks to dispel the position of Geisler and Saleeb thatAllah is the same God (Jehovah) that Christiansand Jews worship, arguingthat Muhammadhimself viewed followers of Moses and Christas "childrenof Satan,not separatedbrethren."The Canersalso assertthat violent jihad and armedconflict is an "essential and indispensabletenet"of Islam. "The [September11] terroristswere not some fringe groupthatchangedthe Koranto suit political ends. They knew the Koranquite well and followed the teachingsof jihad to the letter." This polemic against Islam is not only directedat Muslims; a good partof the book also takesaim at liberalAmericansociety itself. Thus, the Canerswritethatestablishingthe differencebetween the trueGod of Christianityand the false God of Islam is "neitherpopular nor welcome [in a] politically correct,politically charged,postmodernculture.... But [it] is essential to an effective witness."A concern about syncretism,which is the blendingof faiths,andrelativism,holdingthatno one particularfaithis rightor wrong,framesmuch of the Caners'andthe otherpolemicists'arguments,a point thatwill be returnedto laterin this article(See also Schmidt2004: 232-258). Throughoutmuch of the post-9/11 evangelicalliterature,thereis a rethinkingof formerheld views in the light of new realities.A vivid exampleof this is foundin the book Secrets ly the Koran of by popularevangelicalmissionaryDon Richardson(Richardson2003, Staub is who most well-knownfor his book Peace Child.The book is an accountof his mis2003), sionaryexperiencein Indonesiawhere he developed what he calls the "redemptiveanalogy" thesis. This is the idea thateach culturehas some story,ritual,or traditionthatbe used to teachor illustratethe Christiangospel message.After9/11, Richardsonstudiedthe Koran to see if the redemptiveanalogycould be used to buildbridgesto Islambutcame to the conclusion thatit would not work.He writesthatIslam has so redefinedbiblicalteachingsand concepts (such as heaven,Christ,and God) thatit is impossibleto find commonground.In an interview,Richardsonsays thatthe KoranandIslamareessentiallyviolent,claimingthat if Mohammedwas alive today he would supportOsamabin Ladenratherthanmoderates becausehe wantedto createa theocracyon earth.Even in the more moderatepopularbook AnsweringIslam, the updatedpost 9/11 edition (2002: 328) leaves its strictlytheological approachbehindto include a section on "Islamon Violence."Geislerand Saleeb also write that there is a "religiousfoundationfor violence deeply embeddedwithin the very worldview of Islam.... Such violence [goes] to the very roots of Islam, as found in the [Koran] andthe actionsand teachingsof the prophetof Islamhimself."In anotherco-authoredwork with evangelicaltheologianR.C. Sproul,Saleeb reiteratesthe view thatthe violence present amongcontemporaryMuslimsand in Islamicsocieties has its roots in the Koran(Sproul and Saleeb 2003:83-100). 166 No God in Common It shouldbe addedthatthese writersattemptto avoidthe chargeof anti-Islamicprejudice by statingthat most Muslims in the U.S. are not violent and that one should not engage in stereotyping.For instance, in his new book Islam and the Jews, MarkGabriel (2003), an Egyptianand formerMuslim professor,writes thatmost AmericanMuslims are "ordinary Muslims,"meaningthatthey do not reallypracticeIslam as laid down in the Koranand are Muslim because of their cultureand tradition.It is the "committed"and "fanatical"Muslims who are most likely to supportor engage in terrorism,accordingto Gabriel. Islam as a Player in the End-Times Anotherareawhere evangelicalanti-Islamicpolemics have flourishedin recentyearsis in the biblical prophecymovement.This movementgatherstogetherpre-millennialevangelicals and fundamentalists,who interpretthe Bible as providinga blueprintof the endtimes andthe returnof Christ.An importantpartof the premillennialprophecyis the strategic role thatIsraelwill play in gatheringtogetherthe Jews of the worldand rebuildingthe temple, therebyhasteningthe returnof Christto earth.The significantplace given to Israelin such propheticscenarioshas influenceda significantsegmentof the evangelicaland fundamentalistcommunitiesto become steadfastfriendsand supportersof Israel.The tilt toward Israel,at least in contemporarytimes, implies a criticaland at times adversarialview toward the IslamicPalestiniancommunity,which occupies much of the historicalbiblicalterritory. But it is actually only in the last decade that Islam has assumed a centralrole in biblical prophecy. In his book The Last of the Giants (1991) charismaticmissions strategistand futurist George Otis, Jr. writes that since the fall of communismIslam has become the main protagonistin the invasionof Israelfrom neighboringcountriesto the north- the "mostimportantend-timeevents"allegedlyprophesiedin the Bible. The "standardassumption"in early propheticliteraturewas that this invasion would be communist-ledor inspired,but it had always been a puzzle why communists would be in alliance with the Arab nations to the northof Israel.The fall of communismsolved thatproblem,leaving Islam (especially now thatthe religion is active and growingin formerSoviet republics)as the main antagonistin propheticend-timescenarios.Otisgoes on to speculatethatan ultimate"jihad"will be waged againstIsraelby the Islamicnations.While these nationswill be defeated,therewill emerge a miracle-workingfalse prophetknownas the anti-Christ,who Otis identifiesas the "Mahdi," a messiah-likefigurein Shi'ite Islam.The rise of the Mahdiwill signal the beginningof the war of Armageddon,the last battlethatwill usherin the final returnof Christ. The close connectionmade betweenIslam and the unfoldingof biblicalprophecyis evident in other evangelical propheticworks, though not always to the extent found in Otis' writings. Since 9/11 there have been several propheticworks that are based almost completely on the centralrole of Islamin end-timeevents.Hal Lindsey,authorof the 1970s bestseller The Late Great Planet Earth, recently wrote The EverlastingHatred: The Roots of Jihad (2002:10), wherehe chroniclesthe ancientenmity betweenMuslims andJews thatis leading up to the end-times,and adds that"Islamrepresentsthe single greatestthreatto the continuedsurvivalof the planet."In MarkHitchcock'sTheComingIslamicInvasionof Israel (2002), the "finaljihad"between Israeland the Islamic nationstakes center stage. WarOn Terror:UnfoldingBible Prophecy (Jeffrey2002) has a photo of the burningWorldTrade Centeron its coverandfocuses moreon how terrorismitself - fromthe TalibanandAl Queda to even SadaamHusseinin Iraq(in restoringthe biblicalempireof Babylon)- ushersin the end-times. 167 Reviewof Religious Research Charismatic-Spiritual Warfare Literature and the Demonization of Islam The next groupingof charismaticandPentecostalanti-Islambooks andarticlesaresomewhat similarto the apologeticbooks, but they are even more extreme,and tend literallyto demonizethe religion.In this literature,thereis an emphasison whatPentecostalsandcharismaticscall "spiritualwarfare"- thatis, battlingdemonicinfluencethroughthe use of deliverancepractices(similarto exorcism) and performing"signs and wonders"or miraclesto demonstratethe power of God over such forces. This perspectivehas been evident in the decade before 9/11, thoughit has gained a much largerfollowing since 2001. The spiritual warfareperspectiveanimatesmuchof Reza Safa's (1996) popularbook InsideIslam, which was updatedand reissuedafter9/11. Safa touches on all of the familiarthemeslisted above - thatIslamis inherentlyviolentandthatthereis a wide chasmbetweenthe God of the Bible and Allah - but he also introducessome new elements. He writes thatAllah is not only a false god distinctfrom the trueGod of the Bible, but thathe is actuallya pre-Islamicpagan deity who is identifiedwith worshipof the moon. The associationof the occult with Allah and Muslim worshipand practicesis prominentin most of the charismaticand Pentecostal literature.Safa, a convertfrom a "radicalShi'ite"background,writesthatIslamis morethan a religious and a political system; it is a "spiritualforce, an antichristspiritmanifestedto oppose the workandthe plan of God."Islamopposes God's planby hinderingan "end-time revival"of the world (especially since Muslim countriesare closed to Christianmissionaries) as well as by opposingthe Jewishpeople and takingover "theirGod-givenland."Safa concludesthatonly way to conquerIslamis throughtakingauthorityoverthis spiritualforce throughprayerand fasting. Spiritualwarfareteachingshave become entrenchedin charismaticchurchesand teaching centers, and this anti-Islamicpolemic seems to be spreadingthroughthese same networks.Settingmuchof the tone is C. PeterWagner,a formerFullerseminaryprofessorwho trainspastorsandmissionariesin propheticand spiritualwarfareteachingsthrougha school operatedin his name and throughhis organization,Global HarvestMinistries.In a recent issue of his newsletter,he writes that "one billion Muslims worshipa high-rankingdemon who has gone by the name of 'Allah'since long before Mohammedwas born,"and thatthe "deeperdimensionof the waron terrorismis not Talibanvs. America,butAllah vs. God the Father"(Wagner2002:4-5). To understandwhy Islam is so enmeshed in spiritualwarfareteachings among charismatics, it is necessaryto returnto a sourcethatmany of the above authorsand leaderscite: George Otis Jr.'sbook, The Last of the Giants (1991). Aside from its propheticteachings, the book soughtto devise a new map and strategyfor worldevangelization.A new map was necessarybecause"Asthe spiritualbalanceof powerin the worldshiftedsteadilyawayfrom in the 1980s, it becameincreasinglyclearthata new orderof powerfulcomMarxist-atheism was petitors vying for preeminence."Otis identifies Islam as the most serious challenge, since Muslimsmake up much of the 95% of the world'snon-Christianswho reside in what is called the "10/40 window"- a missionarytermmeaningthe geographicalregionbetween the tenthand fortiethlatitudes,includingNorthAfrica, the Middle East, as well as partsof India,Chinaand CentralAsia. Otis sees the 10/40 Windowas the "primaryspiritualbattle groundof the 1990s andbeyond"andidentifiestwo of the region's"powerfulstrongholds"Iranand Iraq.This tendencyto view demonic and even Satanicforces as influencinga territory,a group of people, a government,or an institutionwas conceptualizedby C. Peter Wagneras a way to locate and then expel influencesthatmay block the receptionof Chris168 No God in Common tianityby an unreachedpopulationin a new region.The anti-Islamicpolemic in the charismatic literatureis closely connected to global competition for influence and dominance betweenChristianityandIslam.This is most closely seen in a countrysuch as Nigeria,where Pentecostalshave demonizedIslam in a similarmannerto that of theirAmericancounterparts,althoughthey face the actualthreatof the impositionof Islamic Sharialaw. The Contextualist Approach It would be inaccurate,however,to view the anti-Islamicpolemical literatureas representing the whole evangelicalcommunity.For instance,the trendof missions amongMuslims has moved away fromconfrontationandcondemnationof Islamas a false religionthat must be totally forsakenby the potentialconvertto one of contextualization.This approach teaches thatthe missionarymust meet the Muslims on theirown groundand thattheirculture and religious sensibility should be affirmed,even if ultimately"fulfilled"throughthe Christiangospel. Forinstance,suchmissionarieswouldspeakof God as Allah anduse Islamic prayerand worshippractices(which, it should be added,Muslim critics view as deceitful).TherehavebeenrecentevangelicalbooksthatargueagainstviewingIslamas an essentially violent and evil religion,but they are in the minorityand often exist outsidethe mainstream of the evangelical apologetic movement (Poston and Ellis 2000; George 2002; Mallouhi 2002). Evangelicalmissionarieshave been among those most criticalof these anti-Islamic views. In January,2003, a groupof missionariesfromthe SouthernBaptistConventionsent a letterto its churchleaderspleadingfor a cessation of anti-Islamicstatementswhich only hampermission work among Muslims, not to mentionthreateningthe safety of missionaries themselves (Buettner2003). LynnGreen,the directorof YouthWithA Mission,' called on WesternChristiansto refrainfrom "collectivelydemonizing"Muslimsafter9/ 1 (Dixon 2002). The leadershipof the NationalAssociationof Evangelicalsjoined with an influential conservativethinktank, the Instituteon Religion and Democracy(IRD), in issuing a joint statementof guidelines to calm the evangelical-Islamictensions and initiate dialog. The guidelinescondemnstereotypingIslamandMuslimsandeven affirmthatboth groupsshare a concept of "naturallaw" or "commongrace"in morality and theology (Guidelines for Christian-MuslimDialogue 2003) THE THREAT OF SYNCRETISM AND RELATIVISM The differentforms of anti-Islamoutlinedabove revealnew patternsof competitionand confrontationwith Islam both as a global force and as a presencein the United States.The fact thatthese anti-Islamicpolemics are frequentlystrongeramongAmericanevangelicals than among missionaries,or amongArab and Middle EasternChristianswho have extensive contactwith Muslims, suggests thatthis phenomenonhas as much to do with conflicts andchanges withinevangelicalismas it does with interfaithrelationships.The fearand criticism of religiousrelativismand syncretismin an increasinglyreligiouslypluralisticsociety is common in most of the books and articlesanalyzedin this article.While the concern with pluralismis most evident in the apologetic literature,the message of the charismatic andpropheticliteraturealso reflects the theme thatthe truenatureof Islam is obscuredin a "politicallycorrect"and godless society, as well as in thatsociety's treatmentof the global competitionbetween Islam and Christianity. One can understandthe linkage this literatureoften makes between Islam and violence, especiallysince surveysshow thatotherAmericanshave increasinglycome to a similarposi169 Reviewof Religious Research tion since 9/11. But the evangelical tendencyto drawa sharpline between Christiansand Muslims, including the denial of their belief in the same God, requiresmore exploration. ChristianNews, a conservativeLutherannewspaper,stronglypraisedthe Caners'Unveiling Islam, andrecommendsit both to leadersof the LutheranChurch-MissouriSynod "andthe RomanCatholicPope who assertthatJews,Muslims,etc., all believein the sameGod"(Reising 2003). The referenceto the LutheranChurch-MissouriSynod is importantbecause this churchbody has been embroiledover a controversyinvolvinginterfaithrelations.One of its leaders,David Benke of New York,participatedin an interfaithprayerservicewith Muslims and othernon-Christiangroups at YankeeStadiuma few days after9/11 and was immediately disciplinedby the synod for engagingin syncretismand promotinga false unity with non-Christianreligions.2The incident has served as a case study for evangelicals on the growthof relativismand syncretismin the churches;even the moderateChristianityToday magazinetook an editorialposition favoring,with some qualifications,the synod position. The evangelicalconcernwas thatthe many of the services held, and of the public religious voices heardin the media-even the responseof politicalleadersafter9/11 statingthatIslam is a religion of peace-were close to promotingthe view that Christianityis no different from otherfaiths and thatall religions shouldbe viewed as equal. The relationshipbetween the negativecritiqueof Islam discussed above, and the alarm over religiouspluralismand relativism,is evidentin the coverageof the conservativeevangelical news weekly World,which is one of the evangelical magazines which is the most criticalof Islam. In analyzingWorld'scoverageof Islam, one finds thatbefore 9/11, references to Islam were generallysparse.From 1996 to 1999, for instance,therewere a total of 25 referencesto Islam in articles,mainly havingto do with the persecutionand restrictions againstChristiansin Islamic nations.As one might expect, thatnumberincreaseddramatically in 2001, and in 2002 alone, there were 91 referencesto Islam (usually full articles). Whatis more significantis how these articlesfrequentlyaddressIslamwithinthe framework of a critiqueof pluralismandsyncretismin Americanreligionand society.This is most starkly seen in a controversialeditorialappearingjust after September11 in Worldwhich laid muchof the blamefor the attackson the "godsof nominalism,materialism,secularismand pluralism"(Belz 2001: 5). The magazinelatergave its annual"Danielof theYearAward"(namedafterthe Old Testamentprophetwho faced a lions' den) to FranklinGrahamfor "tellingthe hardtruths.about Islam"as well as for standingup for Christianconvictions in the face of a religiously and culturallyrelativisticsociety."Ina worldof religiousrelativism,the very suggestionthatany one belief mightbe superiorto anotheris preciselythe kind of heresythatwill get a preacher tossed to the lions of politicalcorrectness,"statedthe article(Jones2002: 1-6). In World's editorials,MarvinOlaskyfrequentlystatedthatMuslims and Christiansdo not worshipthe same God and that the violent tendencies of militant Islam are deeply embedded in the Qu'aran(Olasky 2002). But he often placed these views within a broadercritiqueof the Americanmedia as being biased againstconservativeChristiansbut tolerantand uncritical of Islam and othernon-Christianfaiths (Olasky2001, 2003). DISCUSSION September11 and the events surroundingit renderedIslam and pluralismin generalan increasinglyvisible andimmediatepresenceamongevangelicalsthatdemandeda response. 170 No God in Common It was only afterSeptember11 thatinterfaithworshipand prayerbecame a pressingreality and concernin most communities.The media and governmenteffortsto portrayIslam as a peaceful religion and to drawparallelsbetween this faith and othersbecame almost a civic necessity afterthe terroristattacks.NationalMuslim groupssuch as the AmericanMuslim Council and the Council on American-IslamicRelations, together with liberal Christian or groups, attemptedto popularizesuch termsand concepts as "Judeo-Christian-Islamic" "Abrahamic"(referringto Abraham)and to include Islam as an Americanreligion in partnershipwith Christianityand Judaism.The changein terminologywas consideredof symbolic importancefor Muslimstryingto find theirrole in the U.S. afterSeptember11 andthe Iraqwar,yet the strongestoppositioncame from evangelicalgroupsand leaders. Opponentsviewed these developmentsas a new threatto maintainingthe boundariesof evangelicalidentity.Pluralismmeans thatthose holding specific truthclaims are regularly confrontedwith rivaltruthclaims, runningthe risk thatall faithscould be relativizedor that differentelementsof each faithcouldbe sampledandborrowedby uncommittedconsumers. Doctrinesandpracticesthathave servedas boundarymarkersin maintainingthe distinction between theological conservativesand liberals,such as biblical inerrancyand creationism, have given way to new concernsaboutthe blurringof lines between Christianityand other faiths. Recent chargesand disciplinarymeasuresagainsttheologiansby evangelical seminariesand theological associationssuggest that such issues as universalism(thatone may be saved withoutfaith in Christ),syncretism(as demonstratedin the Benke case), and relativism representthe new battlegroundsover heresy as well as the primeboundarymarkers for evangelicalidentityin today'spluralisticsociety (Hunter1987; Olson 2003). Of course, Islam is also opposedto relativismand syncretism.On this point, the conservativeevangelicalpolemics areaddressednot so muchtowardAmericanMuslims,butrather towardsecularistsandreligiousliberalswho are accusedof using religiouspluralismto dismantlenormativeandbiblicalvalues andestablishrelativismin Americansociety.Whathas been called the "thirddisestablishment,"wherereligious pluralismand personalautonomy in belief replacesa collective Protestantethic or "Americanway of life," is most keenly felt truefor thoseof a Reformedor Calvinby theseconservativeevangelicals.This is particularly ist background,as is shown in publicationssuch as Worldmagazine,where the vision of a "ChristianAmerica"still retainsa stronghold (Hammond1992;Casanova1994). Justas the inclusion of Jews and Catholicsinto this once-Protestantsystem generatedearlierconflict, the entranceof Muslims into the public sphereis a new source of dissonancefor conservative Protestants.But the new pluralismis not necessarilya weakeningand destabilizingfactor in terms of maintainingevangelical identity,even though such a scenariois regularly cited to sustainthese polemics. As Smith (1998: 107) argues,a "sacredcanopy"of unified, sharedmeaningon religion is not necessaryto ensurea faith's survival."Inthe pluralistic, moder world, people don't need macro-encompassingsacredcosmoses to maintaintheir religious beliefs. They only need 'sacredumbrellas,'small, portable,accessible relational worlds-religious referencegroups- 'under'which theirbeliefs can makecompletesense." In fact, findingand maintaining"enemies"to the faith tend to have the "unwittingresultof maintainingunityandinternalcohesion."The subculturaltheoryis especiallyhelpfulin this case because the conflict is not solely aboutone largegroup(evangelicals)battlingagainst a minorityreligious group (Muslims), but ratherconcernshow evangelicalsare redefining themselvesin relationto the perceiveddominantculturaland religious forces in a pluralistic society. 171 Review of Religious Research In conclusion,furtherresearchis neededto determinewhetherthe strengtheningof evangelical subculturalidentityin a pluralisticsettingis necessarilycorrelatedwith interfaithtensions andconflict.The case can be (andhas been ) madethatMuslimssharea consensuson severalmoral/socialissues with theirconservativeProtestantcounterparts.In the mid-1990s, there were several calls from Muslim and evangelical leaders and activists to bring both groupstogetherto work on family and otherconservativemoralissues (TheMinaret1997). But any such coalitions have been difficultto sustainbecause many of these same Protestantsretaina vision of a Christian(or at least Judeo-Christian)Americaaccompaniedby a concernto reinforcethe boundariesof theirfaith in an increasinglypluralisticsociety. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authorwishes to thankJose Casanova,as well as the anonymousreviewersand the editor,for theircomments on earlierdraftsof this article.Earlierdraftsof this articlewere presentedat the meetingsof the Associationfor the Sociology of Religion in Atlanta(2003) andthe Society for the ScientificStudyof Religion in Norfolk,Va. (2003). Addresscorrespondenceto RichardCimino, 2869 LawrenceDrive,Wantaugh,NY 11793, relwatch@msn.com. APPENDIX Books and publications surveyed through content analysis Ankenberg,John, and JohnWeldon. 1991. The Facts On Islam. Eugene, OR: HarvestHouse. Caner,ErgunMehmet, and Emir Caner.2002. UnveilingIslam. GrandRapids,MI: KregelPublications. Gabriel,MarkA. 2003. Islam and the Jews Lake Mary,FL: CharismaHouse. Geisler, NormanL., andAbdul Saleeb. 1993. AnsweringIslam. GrandRapids,MI: BakerBook House. 2002. AnsweringIslam. GrandRapids,MI: BakerBook House George,Timothy.2002. Is the Fatherof Jesus the God of Muhammed?GrandRapids,MI: Zondervan. Hitchcock,Mark.2002. The ComingIslamic Invasionof Israel. Sisters, OR: MultnomahPublishers. Jeffrey,Grant.2003. WarOn Terror:UnfoldingBiblical Prophesy.Toronto:FrontierResearchPublications. Lindsey,Hal. 2003. TheEverlastingHatred.Murrieta,CA: OracleHouse Publishing. Mallouhi,Christine.2002. WagingPeace On Islam. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsityPress. Poston, LarryA., and Carl F. Ellis, Jr.2000. The ChangingFace of Islam in America. Camp Hill, PA: Christian PublicationsCo. Otis, Geogre. 1991. TheLast of the Giants:Liftingthe Veilon Islam and the End Times.GrandRapids,MI: Chosen Books. Richardson,Don. 2003. Secrets Of The Koran,Ventura,CA: Gospel Light Publications. Safa, Reza. 1996. Inside Islam. Lake Mary,FL: CharismaHouse. Schmidt,Alvin. 2004. The GreatDivide: The Failureof Islam and the Triumphof the West.Boston, MA: Regina OrthodoxPress. Shorrosh,Anis. 1988. Islam Revealed.Nashville, TN: ThomasNelson Publishers. Spencer,Robert.2002. Islam Unveiled.San Francisco,CA: EncounterBooks. Sproul,RC., andAbdul Saleeb. 2003. The Dark Side of Islam. Wheaton,IL: CrosswayBooks. Trifkovic,Serge. 2002. TheSwordof the Prophet.Boston, MA: Regina OrthodoxPress. Worldmagazine, 1996-2002 issues online at http://www.worldmag.com. NOTES 'A charismaticmissions grouptakinga more liberalposition than otheragencies (as seen in theirclose cooperationwith RomanCatholics). 2Hewas, however,laterclearedby the denomination. 172 No God in Common REFERENCES Ankenberg,John, and JohnWeldon. 1991. TheFacts On Islam. Eugene, OR: HarvestHouse. Belz, Joel. 2001. "Editorial."World,September22, 2001. Buettner,Michael. 2003. "Missionaries:Anti-IslamicStatementsPut Us At Risk,"Associated Press, January19, 2003. Caner,ErgunMehmet, and Emir Caner.2002. UnveilingIslam. GrandRapids,MI: Kregel Publications. Casanova,Jose. 1994. Public Religions In the ModernWorld.Chicago:Universityof Chicago Press. Dixon, Tomas. 2002. "YouthWithA Mission Calls for Reconciliation."Charisma,September,2002. Ethics and Public Policy Center/Beliefnet, "Evangelical Views of Islam," http://www.beliefnet.com/ story/I24/story_12447.html. Gabriel,MarkA. 2003. Islam and the Jews. Lake Mary,FL: CharismaHouse. Geisler, NormanL., and Abdul Saleeb. 1993. AnsweringIslam. GrandRapids,MI: BakerBook House. 2002. AnsweringIslam. GrandRapids,MI: BakerBook House. George,Timothy.2002. Is the Fatherof Jesus the God of Muhammed?GrandRapids,MI: Zondervan. Guidelinesfor Christian-MuslimDialogue. 2003. NationalAssociation of Evangelicalsand the Institutefor Religion and Democracy,May 7, 2003. http://www.ird-reneworg/News/News.cfm?ID=631&c=4 Hammond,Phillip. 1992. Religion and PersonalAutonomy.Columbia,SC: Univ. of South CarolinaPress. Hitchcock, Mark.2002. The ComingIslamic Invasionof Israel. Sisters, OR: MultnomahPublishers. Hoover, Dennis R. 2004. "Is EvangelicalismItchingfor a Civilization Fight?"The BrandywineReview of Faith & InternationalAffairsSpring,2004, pp.11-16. accessed November24, 2003. Hunt,Dave. 2003. The Berean Call web site, http://www.thebereancall.org, Hunter,JamesDavison. 1987. Evangelicalism:TheEmergingGeneration.Chicago:Universityof Chicago Press. IslamOnline, "44% of Americans Back Limits On Muslims' Rights: Poll," December 18, 2004, http://www. islamonline.net/English/News/2004-12/18/article03.shtml. Jeffrey,Grant.2003. WarOn Terror:UnfoldingBiblical Prophesy.Toronto:FrontierResearchPublications. Jones, Bob. 2002. "SpeakingFrankly."World,December 17, 2002, http://www.worldmag.com/world/issue/1207-02/cover_l .asp. Lindsey,Hal. 2002. The EverlastingHatred.Murrieta,CA: OracleHouse Publishing. Mallouhi,Christine.2002. WagingPeace On Islam. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsityPress. Marsden,George. 1991. UnderstandingFundamentalismand Evangelicalism.GrandRapids, MI: Eerdmans. accessed November23, 2003. Morey,Robert.2003. FaithDefenders web site: http://www.faithdefenders.org, Olasky, Marvin. 2001. "IslamicWorldviewAnd How It Differs From Christianity."World,October 27, 2001, http://www.worldmag.com/world/issue/10-27-01/cover_3.asp 2002. "The Big Chill," World, October 26, 2002, http://www.worldmagcom/world/issue/10-26-02/ opening_2.asp 2003. "Coverageof Islam."World,March9, 2003, http://wwwworldmag.com/world/issue/03-09-03/cover_3.asp. Olson, Roger, E. 2003a. "Tensionsin EvangelicalTheology."Dialog, Spring,2003, 76-85. 2003b."TheOpposingArmies of God."Ethics and Public Policy Newsletter,Winter,2003, pp. 1-2. Pew ResearchCenter.2001. "Post-9/11Attitudes."Pew Forumon Religion and Public Life, December 6, 2001, http://www.pewforum.org. 2003. "Surveyon AmericanAttitudesTowardIslam."Pew Forumon Religion and Public Life, July, 2003, http://www/pewforum.org. Plowman, Edward. 2002. "A Little More Conversation." World, November 30, 2002, http://www. 1-30-02/national_l.asp. worldmag.com/world/issue/1 Poston, LarryA., and Carl F. Ellis, Jr.2000. The ChangingFace of Islam in America.Camp Hill, PA: Christian PublicationsCo Otis, George. 1991. TheLast of the Giants: Liftingthe Veilon Islam and the End Times.GrandRapids,MI: Chosen Books. Reising, RichardF. 2003. "UnveilingIslam."ChristianNews, March24, 2003, pp 1, 15. Richardson,Don. 2003. Secrets Of The Koran.Ventura,CA: Gospel Light Publications. Safa, Reza. 1996. Inside Islam. Lake Mary,FL: CharismaHouse. Schmidt,Alvin. 2004. The GreatDivide: The Failureof Islam and the Triumphof the West.Boston, MA: Regina OrthodoxPress. Shorrosh,Anis. 1988. Islam Revealed. Nashville, TN: ThomasNelson Publishers. 173 Review of Religious Research Smith,Christian.1998.AmericanEvangelicalism:Embattledand Thriving.Chicago:Universityof ChicagoPress Spencer,Robert.2002. Islam Unveiled.San Francisco:EncounterBooks Sproul,RC., andAbdul Saleeb. 2003. TheDark Side of Islam. Wheaton,IL: Crossway Books. Staub,Dick. 2003. "Why Don RichardsonSays there's No 'Peace Child' for Islam."ChristianityToday,February 11, 2003, 1-4, http://www.christianitytoday.com/global/pf.cgi?/ct/2003/106/22.0.html TheMinaret,"A Closer Look at the ChristianCoalition."June, 1997, 24-29. Trifkovic,Serge. 2002. The Swordof the Prophet.Boston: Regina OrthodoxPress. Wagner, C. Peter. 2002. "Allah 'A' and Allah 'B'." Global Prayer News, April-June, 2002, http://lyris. strategicprayer.net/cgi-bin/lyris.pl?sub=67908&id=203515133 Worldmagazine, 1996-2002 issues online at http://www.worldmag.com. Wuthnow,Robert.2003. "TheChallengeof Diversity."UnpublishedPresidentialAddressgiven at the conference of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, Norfolk,Virginia,October25, 2003. 174