Explaining Households' Reproductive Behaviour

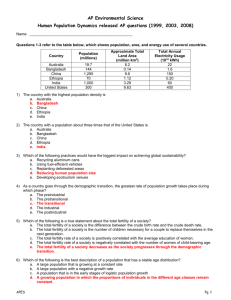

advertisement

EXPLAINING HOUSEHOLDS’ REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR: AN ANALYSIS OF COMPETING MODELS ZIVA KOKOLJ* I. INTRODUCTION For more than four decades, trends in population growth and reproductive behaviour have been researched, subject to theoretical speculation, and targeted by numerous social and economic policies.1 Despite all the attention, however, there exists relatively little consensus on the underlying determinants of fertility behaviour or on the policy measures that may affect population growth (Simon, 1985: 12). While demography per se has become a well established, empirical discipline, it remains “badly in need of theoretical guidance” (Robinson 1997: 63). Although population changes have traditionally been analyzed in the context of macroeconomic development, a significant paradigm shift has taken place since Gary S. Becker's introduction of the ‘new household economics’ in the 1960s. Consequently, microeconomic factors became the prime explanatory variables of household's fertility behaviour. Indeed, it has been noted: “It is a shared tenet […] of almost everyone who works in the area today that fertility tends to respond to shifts in the balance of economic benefits and costs […]. So ubiquitous is the use of such reasoning in discussions of the demographic transition that it [the economic approach] has become virtually the only mode of explanation” (Clealand and Wilson 1987: 5). Despite the general acceptance of the economic framework, however, * Ziva Kokolj is an Undergraduate Student in Political Studies and Economics at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada. 1. Over the past four decades, reproductive behaviour has changed rapidly in much of the developing world. Between the early 1960s and the late 1990s the largest fertility declines occurred in Asia (-52 per cent) and Latin America (-55 per cent), and the smallest in subSaharan Africa (-15 per cent). Although in the 1970s and 1980s the United Nations Population Division predicted widespread fertility declines by 1990s, the actual levels in the 1990s have been lower than the projections indicated. Consequently, the UN 2002 Revision of the official world population projections now estimates “a lower population in 2050 than the 2000 Revision did: 8.9 billion instead of 9.3 billion according to the medium variant.” [See Appendix 1]. For further discussion on the fertility rates trends and population trends see: J. Bogarts, “The End of the Fertility Transition in the Developing World,” <http://www.un.org/esa/population/ publications/completingfertility/RevisedBONGAARTSpaper.PDF> and J. Caldwell, “The Contemporary Population Challenge” < http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/completingfertility/RevisedCaldwellpaper.PDF> 84 SASKATCHEWAN ECONOMICS JOURNAL the standard microeconomic approach - as espoused by Becker and the Chicago school economists - has been subjected to fervent criticism, particularly by those adhering to the institutional, cultural, and behavioural schools of economics. As it has been appropriately remarked, “the dilemma is that there is no consensus on an alternative theory […] the debate [thus] continues with a plethora of contending theoretical frameworks, none of which has gained wide adherence” (Bogarts and Watkins 1996: 641). In light of this impasse, it is the aim of this paper to examine the theoretical frameworks of three competing approaches to explaining households’ fertility behaviour: G.S. Becker’s 'new household economics’ approach, the so-called ‘social determinants’ methodology developed by R.E. Easterlin, and the ‘cooperative conflict’ framework espoused by A.K. Sen. The paper will provide for theoretical assumptions of the three models, as well as for empirical data in their support or opposition. On the basis of this analysis, particular emphasis will be given to the framework developed by A.K. Sen. It will be suggested that the ‘cooperative conflict’ framework has a considerable advantage over the standard economic approaches; not only in light of its capacity to better explain households’ fertility behaviour but also due to its clear implications for appropriate public policy measures. More specifically, this paper concurs with the claim that households’ reproductive behaviour necessitates a gender-based analysis; one that differentiates between gender-specific preferences, accounts for potentially conflicting behaviour within households, and promotes the enhancement of women’s status as an appropriate policy aimed at the reduction of fertility rates. II. EXPLAINING FERTILITY TRANSITIONS The New Household Economics Approach The ‘new household economic’ theory, introduced by G.S. Becker in 1960, provides for the first specific microeconomic model of households’ fertility behaviour. It is based on the familiar neoclassical assumptions of fixed homogeneous preferences, maximizing behaviour, and the existence of an equilibrium solution for all decision situations.2 The “price” of children and households’ real income are used as primary variables for explaining, among other things, why a rise in the wage rate 2. The theory has been variously referred to as the 'demand theory', the 'Chicago School approach' or the 'new household economics.' Becker has developed his theory in numerous articles since 1960. The discussion in this paper is largely based on Becker's 1991 publication of The Treatise of the Family, (Cambridge: 1991), Robinson, 63 3. Household's Utility Function: U = U (n, q, Z1 … Zm). See Becker (1960, 137). 4. Household's Budget Constraint: pn n + Πz Z = I, where I is the total income of a house- HOUSEHOLDS’ REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR 85 of working women typically reduces households’ fertility, and why families with higher income have traditionally had - but do not anymore more children than the lower income households (Becker 1991: 135). Moreover, Becker extends this basic analysis to consider the special interaction between quality (q) and quantity (n) of children. According to Becker, this interaction “explains why the quantity of children often changes over time, even though there are no close substitutes for children and the income elasticity of quantity of children is not large” (Becker1991: 135). Becker’s central argument is that “fertility decisions are economic in that they involve a search for an optimum number of children in face of the economic limitations”(Simon 1985: 37). In line with the axioms of consumer theory, Becker maintains that households maximize a joint utility function, subject to the lifetime budget constraint they are faced with. This assumption implicitly assumes homogenous preferences of all members within the household. As Becker puts it, “the optimal reallocation results form the altruism and voluntary contributions, [as] the group preference function is identical to that of the altruistic head, even when he does not have the sovereign powers”(Becker 1981: 192). The utility function of a household thus includes: the number of children (n), the expenditures on children - assumed as their quality (q) - and the quantities of all other commodities a household consumes.3 Becker relates the idea of utility maximizing to the notion of a household production function. That is, the household itself is the unit producing its own utility by using internal and purchased resources, its own time and labour, and employing a particular ‘household technology’ (Robinson 1997: 63). In other words, the household’s utility is a function of services yielded by the commodities produced within the household, whereby children are modeled as one such commodity (Altman 1999: 30). Since children, along with other commodities, are produced within a household by using time and labour of its members, their costs (pn), and the cost of other commodities (Πz), are incorporated in the household’s budget constraint.4 The household maximizes its total utility by using the constrained total resources available, so as to equate marginal cost to marginal utility of an additional child. This leads to a utility maximizing equilibrium, whereby no reallocation of available resources would increase the total utility of a household (Robinson 1997: 64). hold. In subsequent analysis, whereby Becker includes the interaction of quantity and quality of children, the budget constraint is expanded to include the constant cost of a unit of quality of children (pc) and the total quality of each child (q). The total expenditure on all children within the household thus equals pcqn and the new budget constraint is: pcqn + pzZ = I. This budget constraint is non-linear and depends multiplicatively on n and q. The non-linearity of the budget constraint is in turn responsible for the interaction between quantity and quality described by Becker, 138 -145. 86 SASKATCHEWAN ECONOMICS JOURNAL According to Becker (1991: 14), the demand for children equals “the number of children desired when there are no obstacles to the production or prevention of children.” This demand depends on the relative prices of children and the household’s full income. The relative prices are affected by the direct costs of childrearing (i.e. nutrition, health-care, education) and the net costs of children (i.e. determined by the contribution of children to the household’s income or production function). If relative prices increase, that is if the household’s opportunity costs of having children increase, the demand for children effectively decreases. For example, an increase in the cost of education would increase the relative cost of children, thereby decreasing the household’s demand for children. Similarly, as the costs associated with the time consumed in raising children is an integral part of thid relative cost, and changes in the value of time would significantly affect the demand for children. Indeed, an increase in the value of mother’s time, represented perhaps by a rise in the market wage rate, directly increases the opportunity cost to a woman for having a child, and decreases the demand for children.5 As Becker (1991: 140) asserts, “the growth in the earning power of women during the last hundred years in developed countries is a major cause of both the large increase in labour force participation of married women and the large decline in fertility.” Although an increase in real income of a household generally increases the demand for normal commodities, Becker recognizes that the relationship between children (formulated as normal commodity) and income has largely been violated in the developed world. He contends: “Sometime during the nineteenth century […] fertility and wealth became partially or wholly negatively related among urban families.” While the negative relation between income and fertility would indicate that children’s relative price also increases with income, Becker stipulates: “The interactions of the quantity and the quality of children is the main reason why the effective price of children rises with income” (144). Introducing the notion of ‘child quality’ to the model potentially solves the conceptual problem of a negative relationship between household’s income and the demand for children.6 Moreover, although quality (q) and quantity (n) of children appear to be substitutes, in Becker’s formulation their relationship is multiplicative and interactive; “they do not trade-off against one another, but each is partly determined by the other” (146). Since q and n interact in the demand functions, 5. According to Becker (1991: 140), “household surveys provide direct evidence on the relation between the demand for children and the value of time of husbands and wives. The number of children is strongly negatively related to the wage rate or other measures of the value of time of wives, and is more often positively rather than negatively related to the wage rate or HOUSEHOLDS’ REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR 87 which depend on the market prices and income, they are subject to the usual income and substitution effects. Thus, an exogenous increase in q (or n) of children would reduce the demand for n (or q) of children. This reduction would, however, further increase the demand for q (or n) - again via their multiplicative relationship. The interaction between q and n would continue until a new equilibrium between the two variables is reached. If q and n are close substitutes, the substitution continues until the value of either q or n is negligible. Thus “the ‘special’ relation between quantity and quality of children […] does not presume that they are close substitutes”(Becker 1991: 147). According to Becker it is the interaction between q and n which explains the fertility decline in the developed world. The key change over time, Becker contends, has been a preference shift towards ‘higher quality’ children. In this way the production of children can be said to have become costlier, particularly in terms of increased education and health expenditures (Robinson 1997: 64). Becker (1991: 147) asserts that “the interaction between quantity and quality explains why the education of children […] depends closely on the number of children - even though we have no reason to believe that education per child and number of children are close substitutes.” Furthermore, although women’s participation in the labour market has substantially increased the households’ total income, the time-intensive childrearing has raised women’s opportunity costs of having ‘good quality’ children (Robinson 1997: 64). The combined increase in the relative costs of children has, therefore, led to a decreased demand for children. Similarly, Becker maintains, while family planning programmes can take the credit for initiating the decline of fertility, it is primarily due to the interaction between quantity and quality of children that fertility fell so drastically in the developed world. Becker provides for similar explanation regarding the effects of child mortality and economic development on the fertility decline (151-154). This perspective offers little guidance in terms of potential public policies in countries or regions where fertility rates are particularly high. In a Beckarian world, the households’ fertility behaviour is envisaged as nothing more that a special case of consumer demand, thus subject to changes in income and relative prices (Robinson 1997: 65). The interaction between quantity and quality of children will, according to Becker, inflict higher costs on households, determine lower demand for children, and thus drive the fertility transition and an effective fertility decline. earnings of husbands.” 6. W.C. Robinson notes that the interaction between the quantity and quality of children implies that the demand for children is highly responsive to price and perhaps to income, even when children do not have close substitutes. 88 SASKATCHEWAN ECONOMICS JOURNAL Critique Since its first formulation in the 1960s numerous criticisms have been made of Becker’s household economics. The critique focuses primarily on Becker’s crude assumption of households’ homogeneous preferences, and the improbable postulation of households’ market behaviour.7 Becker’s assertions that changes in relative prices and income are the exclusive determinants of fertility transitions have also been starkly critiqued; the assertions appear not only limited in their explanatory value, but also ignorant of environmental and instrumental conditions which may affect costs, income, and preferences of households.8 The ambiguity of income and substitution effects additionally discredits the realism of Becker’s microeconomic framework. The vagueness of the effects’ strength (i.e. which one will predominate in the process of price or income changes) effectively limits the predictive power of Becker’s model. Finally, Becker’s concentration on empirical evidence from the developed world, as well as the model’s limited applicability to the experiences of the developing countries, have been contradicted by various empirical surveys.9 The above criticisms have led to a series of modifications of Becker’s early formulations of household’s reproductive behaviour. Particular emphasis has thus been laid on the dynamic relationship and the trade-offs between quantity and quality of children, as well as the specification of household preferences.10 Nevertheless, the central tenets of Becker’s analysis remain for some scholars “too narrow to be a significant challenge to demographic transition theory” (Kirk 1996: 370). As W.C. Robinson (1997) critically notes: The theory [Becker/Chicago demand theory of fertility] has become complex and somewhat esoteric. In fact, most of its assumptions and prepositions are not essential to the theory’s ability to explain fertility declines as economic development occurs. [Moreover] most of the theoretical complexity is self-driven and far removed form policy considerations … It has become dominant because of its rigour, its elegance and its simplicity.… Yet, this theory leaves out many important considerations and glosses over important difficulties which seriously impair its usefulness as a guide to policy interventions.11 7. For elaborate criticism on these two counts see Sen (1990). 8. For details on these see W.C. Robinson (1997), 443-454. 9. Surveys of individuals in 42 developing countries did not find the expected dominant influence of socio-economic characteristics of fertility (Clealand and Wilson 1987). This and other surveys have demonstrated that there is no tight link between development indicators (i.e. GDP per capita, relative prices etc.) and fertility. Most traditional societies do have high fertility when compared to modern industrial societies, but the transition itself is poorly pre- HOUSEHOLDS’ REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR 89 III. THE SOCIAL-DETERMINANTS SCHOOL OF THOUGHT In the ‘new home economics’ approach espoused by Becker, the burden of explanation is put on income, relative prices and the interaction between quantity and quality of children. A number of authors, however, suggest that families differ fundamentally in the value they place on children, and that social and biological constraints placed on families are the primary determinants of fertility rates. Thus, they argue, a microeconomic model of household reproductive behaviour should treat preferences and biological bias of reproduction as explanatory variables (Simon 1985: 42). R.E. Easterlin makes a sophisticated effort to combine economic decision-making process with the social and biological constraints to which it is subject (Clealand and Wilson 1987). He broadens the traditionally defined factors of demand, supply, and cost of fertility regulation, thereby providing for a model of much greater flexibility and scope than the strict microeconomic approach allows (Clealand and Wilson 1987). Under the category of ‘demand factors’ influencing fertility, Easterlin includes the standard socio-economic determinants associated with the economic development and modernization. Moreover, while the ‘supply factors’ are comprised of cultural elements that constrain natural fertility, costs of fertility regulations are the monetary, time and psychic constraints incurred by the use of birth control (Kirk 1996: 370). According to Easterlin (1985: 370), “all determinants of fertility operate through one of these variables.” In keeping with the economic theory of household choice, Easterlin assumes the immediate determinants of the demand for children to be: income, prices, and tastes. Like Becker, Easterlin assumes homogenous preferences, expressed by the joint utility function of households. The latter contains as its arguments the number and the quality of children, as well as other goods consumed by the parents (Simon 1985: 45). Easterlin (1985: 14) defines the demand for children (Cd) as “the number of surviving children parents would want if fertility regulation were costless.” The potential supply of children (Cn) is, according to Easterlin, “the number of surviving children a couple would have if they made no deliberate attempt to limit family size” (1985: 14). The supply of children reflects both the couple’s natural ferdicted by customary quantitative measures of development. See also J. Bogarts and S. Cotts (1996), 639 - 682. 10. See Becker’s “A reformulation of the Economic Theory of Fertility” in G.S. Becker The Treatise on the Family (1991). 11. Robinson (1997) provides an elaborate critique on the drawbacks of Becker’s theory on pages 65 - 70. 90 SASKATCHEWAN ECONOMICS JOURNAL tility and the chances of child survival. Moreover, it is directly influenced by cultural conditions “such as prolonged breastfeeding that inadvertently reduce fertility.” Critical to Easterlin's model is the introduction of fertility regulation costs (RC) born by the household. These include two types of costs: physic costs - caused by the displeasure associated with the very idea of fertility control - and market costs - embodied in time and money necessary to learn about specific fertility control techniques. The costs, in turn, are determined by the attitudes in society toward fertility regulation, and the degree of access to fertility control. Easterlin also accounts for the motivation necessary for implementing fertility regulations. According to Easterlin (1985: 17), motivation is jointly determined by potential supply and demand for children: if the former exceeds the latter - leading to an ‘excess supply’ situation - parents may be faced with the prospect of having ‘unwanted children.’ Thus, the greater is the potential burden of children to the household, the stronger is the motivation to limit fertility. Motivation for fertility regulation is, however, also affected by the costs of fertility regulation. Easterlin (1985: 18) contends: “Given the strength of the motivation, the lower the cost of fertility regulation - […] - the greater would be the adoption of fertility regulation and the more nearly would the number of children parents have correspond to the number they desire.” According to Kirk (1996), “Easterlin’s framework envisages modernization as influencing fertility through intervening variables of supply, demand, and cost of controlling births.”12 In his model, supply and demand for children are not a function of price, as it is the case in the standard microeconomic model, but rather of the process of modernization (i.e. of time) (Altman 1999: 30). This assumption allows Easterlin to explore a number of equilibrium solutions for the individual household, as well as for society as a whole, as it moves through time from situations of excess demand to the those of excess supply and of restricted fertility (Simon 1985: 46). According to Easterlin (1985: 25), “modernization tends, on balance, to lower the demand for children, raise the potential supply, and reduce the regulation costs.” Since early in the modernization process the demand for children exceeds supply, and the costs of fertility regulations are relatively high, the motivation for a household to regulate fertility remains relatively low. However, as modernization progresses, the excess supply of children grows and the 12. In Easterlin’s (1985) formulation the top five effects of modernization on fertility are: (1) innovations in public health and medical care, (2) innovations in formal schooling, (3) urbanization, (4) the introduction of new goods, and (5) the establishment of the family planning program. Easterlin, however, admits there are many other aspects that influence fertility, such as the per capita income growth, female employment in the modern sector, modernization of HOUSEHOLDS’ REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR 91 cost of fertility regulations decreases. The burden of ‘unwanted children’, and the lower cost of fertility regulation, induces the motivation to limit fertility, until “at some point the balance between the motivation for the regulation and the costs of regulation tips in favour of the former” (Easterlin 1985: 25). At this point, the number of actual surviving children begins to fall below the potential supply, until a level of fertility is reached at which the actual number of children “supplied” corresponds to the number of children demanded. Critique Easterlin’s main contribution to the study of households’ reproductive behaviour is the addition of the social component (i.e. the supply of children) and the cost of contraceptives. Moreover, the flexibility of Easterlin’s model is enhanced by the fact that it does not assume either priority or dominance among different economic, socio-economic or cultural explanations.13 Nevertheless, Kirk (1996: 371) contends that “its practical application faces difficulties.” First, Easterlin, like Becker, ignores gender-specific preferences and avoids issues of uncertainty and conflict within households. Although Easterlin does suggest that biological factors, and the variables related to household preferences, will explain fertility differentials, his model does not provide for explicit guidelines as to how these factors should be incorporated into the “empirical science of fertility” (Bulatao and Lee 1983: 46). Second, there is a lack of precise definition of ‘demand’ and ‘supply’ of children. A number of factors can be conceptualized to work either through the supply or the demand side of the model (i.e. the mortality rate is a prime example of a factor working through both sides of the model). Finally, Easterlin assumes a cohort rather than period perspective, which proves difficult for the analysis of current events. He assumes a fixed life cycle (i.e. parents decide at the time of their marriage what number of children they want), and does not allow for any effects of changes with time and experience (Kirk 1996: 371). IV. THE NEED FOR EXPANDED CRITERIA Despite the complexity of the above-described approaches, empirical tests have not led to sufficient support for the models. It appears, government administration, and changes in human attitudes and personality. Easterlin, 20. 13. It is exactly this characteristic that induced the National Research Council’s Panel on Fertility Determinants to adopt it as the basic framework for its massive study. See: R.A. Bulatao and R.D. Lee (1983). 92 SASKATCHEWAN ECONOMICS JOURNAL therefore, “that present theories do not capture the most important elements in the process, which determines fertility at either household or societal level” (Bulatao and Lee 1983: 49). Demographic evidence suggests that, while the demand for children over the past fifty years experienced a drastic fall in less developed countries, the supply of children has remained unchanged (Altman 1999: 32). Despite the broad provision of fertility regulations (i.e. particularly in the form of family planning programs), the number of surviving children in developing countries does not correspond to their actual demand. Consequently, most developing countries now face a situation of excess supply of children. Demographic surveys further contradict the standard microeconomic approach by suggesting that neither the demand for children nor the excess supply situation is solemnly a product of economic variables (Altman 1999: 33) [See discussion below]. Although the negative relationship between economic development (i.e. modernization, industrialization, an increase of per capita income) and fertility is not explicitly rejected, a significant fertility decline has been achieved in countries where economic development has traditionally been slow (as has been the case in Bangladesh). The apparent paradox thus suggests that fertility transition theories should be formulated independent of, or controlling for, economic variables (Altman 1999: 32). Several innovative approaches have thus been introduced to the study of fertility transition. Most of the approaches have relaxed the assumption of homogeneous preferences within households, assuming instead heterogeneous preferences among men and women. Moreover, they have assumed the relationship within households to be one of cooperation and conflict, rather than benign submission to the preferences of an altruistic head. Finally, they have focused extensively on the bargaining powers among members within households; particular attention has, thus, been given to the position of women within the bargaining framework, and to the potential effects of women’s empowerment on households’ fertility. This paradigm shift in the study of households’ fertility behaviour has occurred primarily due to the empirical findings that suggest the existence of differential reproductive preferences between men and women. An extensive body of literature contends that social roles and power relations among men and women have important implications for the determination of fertility levels of a particular country. Oppenheim and Taj (1987: 611) thus assert “most of the information gathered through fertility surveys suggested that women consistently desire smaller families than their husbands.” Additionally, they claim “there is greater demand for children among women than men in settings in 14. A gender system is defined by Oppenheim and Taj (1987) as "the socially constructed expectations for male and female behaviour that are found (in variable form) in every known HOUSEHOLDS’ REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR 93 which women are relatively powerless.” Although, it remains unclear whether certain gender-systems, or particular socio-economic conditions, or a combination of both, cause the differentiated preferences among men and women, empirical research provides for clear verification of their existence.14 As noted above, the standard economic view assumes households to represent singular decision-units - units concerned with, among other things, the allocation of consumption, work, leisure, health-care, education, and fertility. Dagsputa (1995: 1885) correctly observes that the standard economic perspective tends not only to idealize the household’s decision-making (i.e. without disagreements or divergence of preferences within the household), but also to identify household’s behaviour with “a unitary view among its members of what constitutes their well-being.” In view of the household’s homogeneous preferences, standard economic theory also predicts the same level of demand for children by both male and female member of the household. Yet Dasgupta (1995) warns that empirical studies do not tend to support the notion of homogenous preferences and choices. Income in the hands of the mother, for example, has a bigger effect on the family’s health (i.e. in terms of nutritional condition of children, child mortality etc.) than the income allocated by the father. Diverging household tastes are also evident in the case of childbearing. Holding relative prices, opportunity costs and levels of income constant, Altman’s (1999) findings suggest lower demand for children by women than by men. The results of his study are generated from a gender-specific utility maximization model which, allowing for differences in tastes, illustrates that women tend to perceive the marginal benefits of having children as much smaller than their marginal costs. Oppenheim (1997) offers a partial explanation for this finding. He suggests that due to their physiological role in reproduction, women face unique costs in having children, including pain, exhaustion and elevated risk of morbidity and mortality associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding. While these costs are relatively low under modern conditions - where women’s health and nutrition are good, medical assistance is available, and conception is controlled - in developing countries these costs may be extremely high. Dasgupta (1995) makes a similar argument that rational, utility-maximizing women of the developing world would be expected, given the choice to do so, to opt for fewer children than men. Additionally, it has been observed, that socially and culturally induced differences between sexes are likely to determine the degree of divergence between male and female reproductive goals. Oppenheimer human society. A gender system’s expectations prescribe a division of labour and responsibilities between women and men and grant different rights and obligations to them.” 94 SASKATCHEWAN ECONOMICS JOURNAL (1997) suggests that if the division of labour by gender is minimal and the power distribution between the sexes is equal, reproductive preferences are expected to converge (i.e. as it is usually the case in Western democracies). Conversely, in situations where strong division of labour and power exists between the sexes, the dominant sex’s reproductive decisions are likely to prevail.16 It has been argued, therefore, that women’s expressed preferences may not always be their “true” preferences (Sen, 1984). Empirical evidence suggests that in most contemporary developing countries, where rising rates of fertility growth are present, gender-biased divisions of labour and power are fairly marked. The relationship between gender inequality and fertility growth is particularly strong in areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and South East Asia. Finally, it is reasonable to expect lower birth rates in societies where women have greater ability to express and institute their preferences. Empirical studies on the status of women in the developing countries tend to confirm this assumption.17 According to McDonald (2000), the data display “an unmistakable pattern: high fertility, high rates of female illiteracy, low share of paid employment, and a high percentage working at home for no pay - they all hang together.” V. COOPERATIVE CONFLICT In light of the existence of heterogeneous preferences, the standard assumption of benign relationships within households appears artificial. The artifact of pure benevolence within households is particularly evident in societies where gender-bias and stratification of sexes are strongly present (i.e. in the countries that are currently undergoing fertility transition and which the models illuminated above are attempting to address). An alternative analysis of household behaviour - particularly of household’s fertility behaviour - should therefore account for potential divergence of interests. In other words, the analysis should account for the potential co-existence of conflict and cooperative rela16. Literature suggests several circumstances in which women and men are likely to have different family size preferences. These conditions include (1) when patriarchal systems are strong, (2) when economic conditions are premodern, (3) when kinship system is lineage oriented, and (4) when certain demographic conditions - a high average rate of fertility, a large average age difference between spouses, and a low rate of remarriage - obtain. For an in-depth discussion on these see: K. Oppenhein and Taj (1987). 17. Most of the empirical research has focused its surveys on women and the most common dilemma among researchers is the lack of an agreement as to how the concept of women empowerment should be defined and measured. Since women’s authority, as well as reproductive attitudes and practices, can be measured in different ways results of empirical studies differ substantially depending of the indicators used. For an elaborate critique of this approach see McDonald (2000). 18. The classic formulation of Nash’s bargaining problem is outlined as follows: n = 2, with both players having clearly defined utility functions. If parties fail to cooperate, this leads to HOUSEHOLDS’ REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR 95 tions within households. Perhaps the most influential analysis of household behaviour has been proposed by A.K. Sen, who envisaged “fertility determination between female and male […] as a repeated bargaining game which takes the form of cooperative conflict […]”(Altman 1999: 35). While Sen’s model of inter-household relations is formally based on Nash’s (1950) bargaining problem, Sen expands the model in several ways conducive to the understanding of household reproductive behaviour.18 The simplest structure of the ‘cooperative conflict’ model assumes the coexistence of two players within the household, each with a unique, well-defined utility function. While the two players can choose between cooperation and conflict, the failure to cooperate leads to the ‘breakdown position’ (in the present context this could be defined as a decision to have no children at all or even dissolution of the marriage arrangement). The bargaining problem arises from the existence of many collusive arrangements, whereby each such cooperative outcome is better for both persons than that obtained under non-cooperation (Sen 1995: 132). According to Sen (1999: 132-33), “it is this mixture of cooperative and conflicting aspects in the bargaining problem that makes the analysis of the problem potentially valuable in understanding intra-household behaviour.” The bargaining problem of ‘cooperative conflict’ - that is, finding a particular cooperative outcome which yields a particular distribution of benefits - is sensitive to various parameters closely related to the bargaining powers of household’d members. Sen identifies three particularly strong influences affecting the bargaining power and the position of the parties involved: (1) the nature of the breakdown position, (2) the impact of the perception of interests, and (3) the effect of the perception of contributions to the household’s well-being.19 The breakdown position indicates a person’s vulnerability or strength in the bargaining process; a more favourable position in the case of a breakdown would tend to secure a more favourable bargaining the ‘status quo’ or the ‘breakdown position.’ The situation of ‘status quo’ can be avoided or improved through cooperation and bargaining between the parties. Although cooperative positions are superior to the ‘breakdown position’, not all are equally good for both parties. Nash proposes a particular Nash Solution to the bargaining problem. For further discussion on the benefits and drawbacks of the bargaining structure interpretation of household behaviour see Sen (1990). 19. It is important to account for the following conditions - which were avoided by other bargaining problem formulations - in the setting up of the ‘cooperative conflict’ model: (1) one must distinguish between the perception of interests of both parties and some more objective notion of their respective well-being. Sen (1990) focuses on the ‘capabilities’ of - the functionings of - a person which provide for a direct approach to measuring a person’s well-being rather than the indirect and subjective approach via utility measurement (i.e. measurement of happiness and satisfaction). (2) Information base of the ‘bargaining problems’ (typically confined to the individual’s welfare and interests) must be expanded to distinguish between the 96 SASKATCHEWAN ECONOMICS JOURNAL outcome (Sen 1984: 375). For example, if men typically have better bargaining power than women - which may be related either to better outside job opportunities and possibly connected with persistent inequalities of education or training, or to sexist discrimination - this tends to provide them with a correspondingly more favourable cooperative outcome. Conversely, frequent pregnancy and persistent childrearing, along with greater illiteracy, lower education, and scarcer opportunities to participate in the labour market, hamper women’s bargaining power along with their ability to secure favourable cooperative outcome (Sen 1995: 137). Perception of interests by the bargaining parties tends to exert a significant bias on the positioning of the parties. According to Sen (1995: 139), “a person might get a worse deal in the collusive solution, if his or her perceived interest takes little note of his or her well-being.” Such perception bias in the interest of other family members is likely to apply particularly to women in traditional societies. Perceptions of contributions to the well-being and the welfare of a household tend to exacerbate the unequal positioning of the bargaining parties. Although the perception of who is producing and providing what might diverge form the actual contributions, the perceptions may be important in tilting the cooperative outcomes in favour of the perceived contributor (Sen 1995: 136). Moreover, the perception of larger contributions might also affect the legitimacy of the allocation of certain benifits where the perceived contributor might be legitimately entitled to a larger share of such benefits (Sen 1998: 106). In situations where women are confined to work within households, while men earn an income from the outside market, the male productive role is often perceived as more important than the female role. It has been noted, for example, that women tend to fare relatively better in societies where they play a significant role in the acquisition of food and earnings from outside of the household; in such settings, women’s contribution to the welfare of the household enhances the perception of women’s input, and ensures her a stronger position within the bargaining process (Sen 1998: 106). Sen (1984) also notes that the differential advantages between men and women can feed on themselves. A better deal for the male in one portion of the bargaining process can, inter alia, secure a better position in the division of labour, better training, or more profitable job experience. This, in turn, can lead to a better placing in the next period’s barinterest, perceptions, and the measures of well-being. (3) Measures must include information about “who” is contributing “how much” to the overall family prosperity. This in turn determines the perception of legitimacy and obligation of a particular party. 20. For a detailed discussion on this approach see Sen (1985). HOUSEHOLDS’ REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR 97 gaining problem. Certain ‘traditional’ arrangements can thus emerge, whereby “the asymmetries of immediate benefits, sustain future asymmetries of future bases of sexual divisions, which in turn sustain asymmetries of immediate benefits”(Sen 1995: 137). VI. CAPABILITIES APPROACH AND FERTILITY REDUCTION It is important to recognize that Sen is at variance with the standard economic theory in another significant element - the evaluation of a person’s well-being. While standard economic models evaluate a person’s well-being in terms of singular notion of utility - where utility represents whatever object of desire the individual or household maximizes - Sen distinguishes between two ways of seeing a person’s interests and their fulfilment: the person’s well-being, and his or her agency.20 This distinction is important not only because it differentiates Sen’s model from the traditionally rigid economic frameworks, but also because of the significance it has in terms of Sen’s public policy recommendations for fertility rate reduction. The conception of well-being, as employed by Sen, is concerned primarily with a person’s actual achievements. It cannot be judged either in terms of commodities or in terms of mental metrics of utilities. Rather, it must be understood in terms of a person’s capabilities. In other words, the well-being of a person must be understood in terms of what he or she is capable of ‘doing’ and ‘being’.21 According to Sen (1984: 376), “this is the perspective of ‘freedom’ in the positive sense: who can do what, rather than who has the bundle of commodities, or who gets how much utility.” This ‘capabilities approach’ evaluates individuals’ well-being as a function of positive freedoms which they can enjoy within the context of the household and society at large. While personal capabilities achieved by a person necessarily vary with the economic prosperity of a particular setting he or she is in, the perspective of capabilities provides for a relative - rather than absolute - judging measure. For example, Sen (1984) makes reference to the capacity to be free from hunger and to meet nutritional needs, an acheivement that is widely relevant in judging well-being in a poor country, though typically not so in a rich country in which this capability is typically unproblematic (except for specially deprived groups). Sen also introduces the important concept of ‘agency.’ Although the agency of a person is necessarily linked with his or her well-being, the delicate distinction between the role of a person as an “agent” and 21. Some of the most elementary functionings of a person are: the ability to be well nourished, to avoid escapable morbidity or mortality, to read and write and communicate, to take part in the community, and to appear in public without a shame. See also Sen (1985). 98 SASKATCHEWAN ECONOMICS JOURNAL “patient” that fundamentally determines the ways and extent that such freedoms are realized. This elementary difference between the wellbeing and the agency of a person is especially important in light of the debate of social justice and women’s rights.22 While the relative deprivation of women’s well-being remains a pending concern to the debate, it is the limited role of women’s active agency - particularly with respect to their ability to control their reproductive functions - that is most crucial to women’s ability to enjoy basic civil liberties. According to Sen (2000b: 198), “the adverse effects of high birth rates powerfully include the denial of substantial freedoms - through persistent childbearing and child rearing - routinely imposed of many Asian and African women.” Empirical work of recent years has demonstrated very clearly how the relative strength of women’s agency is directly influenced by such variables as women’s literacy and education, their ability to earn independent income, to find employment outside of the household, and to actively participate in decision-making within and outside of the household (Sen 2000b: 191). Although these factors may appear to be diverse and disparate, they all have in common a positive contribution to the force of women’s voice and agency through greater independence and empowerment. Nevertheless, the factors displaying the most statistically significant effect on the fertility rates are female literacy and female labour force participation (Sen 2000a). The negative linkage between female literacy and fertility has been widely observed in most countries undergoing fertility transition.23 According to Sen (2000b: 199), “the unwillingness of educated women to be shackled to continuous child rearing clearly plays a role in bringing about this [fertility rate] change.” The influence of education on fertility is assumed to derive from various dimensions of educational experience. Martin (1995) notes that while schooling provides for advancement of literacy skills, it also stimulates cognitive development and enables students to process a wide range of information. Moreover, education acts as an important agent of socialization; it shapes attitudes, opinions and values of the educated. Similarly, education enhances women’s economic opportunities and can be considered as a vehicle for social mobility (Martin 1995: 189). Each of these factors contribute to women’s agency and, in turn, to both their desire and ability to chose fewer children. Women’s education alone, therefore, can exert substantial influence on the revealed reproductive preferences of women. Although fer22 The 1994 Cairo Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) focused attention on the role of women's empowerment in influencing reproductive behaviour. 23 The powerful effect of female literacy contrasts with the completely ineffective roles of HOUSEHOLDS’ REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR 99 tility norms are strongly related to the economic organization of a particular society, its cultural setting, and its family structure, Sen (2000b: 192) notes that when controlling for these variables “the observed fertility among better educated women is close to their desired family size, [while] the actual fertility of unschooled women is usually twice their stated ideal size.” As education helps mothers to process information more effectively, it also enables them to use various social and community services more intensely (Dasgupta 1995: 1887). An increased level of education, therefore, appears complimentary to the efforts of family planning programmes, to the active use of fertility regulations and, consequently, to the reduction of fertility rates. Finally, Sen (2000a: 218) points out that school education can enhance a woman’s decision-power within the family, particularly “through its effects on her social standing, her ability to be independent, her power to articulate, her knowledge of the outside world, her skill in influencing group decision and so on.” The economic dependency of women on men plays another significant role in women’s ability to express, and implement, their fertility desires. This is particularly the case in traditional societies where women are confined to long hours of work at home, work that is often ignored in the accounting for the respective contributions of women and men to the household’s overall prosperity (Sen 2000b). Accordingly, men’s relative dominance - connected to their position as “breadwinner,” whose economic power commands respect within the family tends to take precedence in the household’s reproductive decisions. There is considerable evidence, however, that when women can participate in the economic activities outside of the household, this tends to enhance not only their relative position within the household (i.e. in terms of the perceived share of contribution to the well-being of the family, thus, in terms of women's bargaining position and power), but also within the society.24 In light of the above evidence - which suggests a positive impact of education and economic participation on women’s agency - it is reasonable to explain an observed decrease in birthrates in some societies in terms of an improvement of women’s overall status and power within those societies. Although it is important to recognize that correlation is not causation, there are reasons for thinking that political and civil liberties of women are not only desirable in themselves, but also have an instrumental role in the reduction of fertility rates across the developing world. While gender equity - resulting form equal capabilities of men male literacy or general poverty reduction as instruments of fertility change. For further discussion see Sen (2000b). 24 For further discussion on the enhancement of women’s agency via economic participation see: A. Sen Development as Freedom, P. Dasgupta, 'The population Problem' etc. 100 SASKATCHEWAN ECONOMICS JOURNAL and women to pursue their well-being and agency - is not a sufficient condition for an effective fertility transition, it is a necessary one. Consequently, in an attempt to reduce fertility rates, particular attention should be given to public policies, which enhance gender equity and the freedom for women. The pursuit of such policies is important not only for the reduction of fertility rates per se, but also for the improvement of social justice and economic prosperity of women as well as men throughout the developing world.25 VII. CONCLUSION It has been the aim of this paper to advocate the need for revision of standard economic assumptions with respect to the household’s reproductive behaviour and decision making. By comparing three competing approaches, we emphasize that any study of fertility behaviour should take into consideration the existence of heterogeneous, genderbased preferences, and potentially conflicting behaviour within households. This is necessary not only to enhance the accuracy of the model but also for determining the appropriate public policy responces to overtly high fertility rates and population growth. In light of the various frameworks outline above, A.K. Sen’s model of ‘cooperative conflict’ appears to be the most far-reaching in describing the mechanisms behind households’ reproductive behaviour. While the standard microeconomic model proposed by G.S. Becker indeed provides quantifiable measures for the demand for children, its foundations suffer significant shortcomings. The assumptions of households’ homogeneous preferences and benign relations among household members are simplifications that tend to blur crucial dimensions of household behaviour. Moreover, the ambiguities concerning substitution and income effects raise scepticism over the validity of the model’s predictions. While the special relation between quantity and quality of children is supposed to “explain” the negative relationship between households’ income and the demand for children, the definition of children’s “quality” itself is rather vague and its connection to observed fertility transitions remains uncertain. Similarly, the economic framework developed by R.E. Easterlin while expanded to include the social component of fertility behaviour and the cost of contraceptives - also fails to gain credible empirical affirmation. Although the relationship between modernization and declining fertility rates has indeed been observed, the large variation in fertility rates across more developed or “modern” economies emphasizes the omission of important explanatory factors. 25. For discussion on gender equality and social justice see Sen (1995). HOUSEHOLDS’ REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOUR 101 In his willingness to depart from the simplifying assumptions concerning household decision-making of the standard models, A.K. Sen considers how the interaction of gender-based preferences - via bargaining process between the two parties - can explain the number of children in a household. Perhaps the most important contribution of Sen’s model is its clear implication for public policy. His ‘capabilities approach’ to evaluating an individual’s well-being illuminates the necessity for respect of each individuals’ basic rights and liberties. More importantly, it advocates the enhancement of women’s rights and capabilities, through the promotion of higher education and social status, as the most appropriate and effective measure for achieving fertility rate reduction. Consequently, the model is conducive not only to the betterment of women’s physical and social condition, but also to the expansion of social justice. REFERENCES Altman, M. (1999). “A Theory of Population Growth When Women Really Count.” Kyklos (52): 27-44. Bulatao, R.A. and Lee, R.D. (1983). Determinants of Fertility in Developing Countries. New York. Becker, G.S. (1991). The Treatise on the Family. Cambridge. Bogarts, J. “The End of Fertility Transition in the Developing World” [online]. [cited 20 February,2003] <http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/ completingfertility/RevisedBONGAARTSpaper.PDF> Bogarts, J. and Cotts Watkins S. (1996). “Social Interactions and Contemporary Fertility Transitions.” Population and Development Review (22): 639 - 682. Caldwell, J.C.(2003). “The Contemporary Population Challenge.” [online]. [cited 20 February, 2003] <http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/ completingfertility/RevisedCaldwellpaper.PDF> Clealand, J. and Wilson C. (1987). “Demand Theories of the Fertility Transition: An Iconoclastic View.” Population Studies (41): 5-30. Dagsputa, P. (1995). “The Population Problem: Theory and Evidence.” Journal of Economic Literature (33): 1879 - 1902. Easterlin, R.A. and Crimmins E.M. (1985). The Fertility Revolution: A SupplyDemand Analysis. Chicago. Kirk, D. (1996). “Demographic Transition Theory.” Population Studies (50): 361 - 387. Martin, T.C. (1995). “Women's Education and Fertility: Results form 26 Demographic and Health Surveys.” Studies in Family Planning (26): 187 202. McDonald, P. (2000). “Gender Equity in Theories of Fertility Transition.” 102 SASKATCHEWAN ECONOMICS JOURNAL Population and Development Review (26): 427 - 439. Nussbaum, M.C. (1995). “Human Capabilities, Female Human Beings.” In Women, Culture and Development: A study in Human Capabilities, ed. Nussbaum M.C. and Glover J.. Oxford. Oppenheim, Mason K. (1997) “Explaining Fertility Transitions.” Demography (34): 443- 454. Oppenheim, Mason K. and Malhorta Taj A. (1987). “Differences between Women’s and Men’s Reproductive Goals in Developing Countries.” Population and Development Review (13). Robinson, W.C. (1997). “The Economic Theory of Fertility Over Three Decades.” Population Studies (51): 63 - 74. Sen, A.K. (1984). Resources, Values and Development. Oxford. Sen, A.K. (1985). Commodities ad Capabilities. Amsterdam. Sen, A.K. (1990). ‘Gender and Cooperative Conflict' in Persistent Inequalities: Women and World Development, ed. I. Thinker, New York. Sen, A.K. (1995). “Gender Equality and Theories of Justice.” In Women, Culture and Development: A study in Human Capabilities, ed. Nussbaum M.C. and Glover J.. Oxford. Sen, A.K. (1998) “Co-operation, Inequality and the Family.” In The Earthscan Reader: Population and Development, ed. Dement P. and McNicoll G. London. Sen, A.K. (2000a). “Population, Food and Freedom.” In A.K. Sen. Development as Freedom. New York. Sen, A.K. (2000b) “Women's Agency and Social Change.” In A.K. Sen Development as Freedom. New York. Simon, G.B. (1985). Fertility in Developing Countries: An Economic Perspective on Research and Policy Issues, ed. G.M. Farooq and G.B. Simon. New York. United Nations (2002). World Population Prospects: The 2002 Revision [online]. [cited 15 March, 2003] <http://www.un.org/esa/population/ publications/wpp2002/WPP2002-HIGHLIGHTSrev1.PDF>