Click here to see a sample from Chapter 6.

advertisement

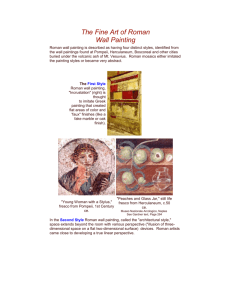

ETRUSCAN ART AND ROMAN ART FEROCIOUS SHE-WOLF TURNS TOWARD us with a vicious snarl. Her tense body, thin flanks, and protruding ribs contrast with her heavy, milk-filled teats. Incongruously, she suckles two active, chubby little boys. We are looking at the most famous symbol of Rome, the legendary wolf who nourished and saved the city’s founder, Romulus, and his twin brother, Remus (fig. 6-1). According to a Roman legend, the twin sons of the god Mars and a mortal woman were left to die on the banks of the Tiber River by their wicked uncle. A she-wolf discovered the infants and nursed them in place of her own pups; the twins were later raised by a shepherd. When they reached adulthood, the twins decided to build a city near the spot where the wolf had rescued them, according to tradition, in the year 753 BCE. This composite sculptural group of wolf and boys suggests the complexities of art history on the Italian peninsula. An early people called Etruscans created the bronze wolf about 500 BCE, and Romans added the sculpture of children to it in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century CE. This figure is thus a fitting image for the way the themes and styles of the Etruscans and the later Romans combined. We know that a statue of a wolf—and sometimes even a live wolf in a cage—stood on the Capitoline Hill, the governmental and religious center of ancient Rome. But whether the wolf in figure 6-1 is the same sculpture that Romans saw then is far from certain. According to tradition, the original bronze wolf was struck by lightning and buried. The documented history of this She-Wolf begins in the tenth century CE, when it was rediscovered and placed outside the Lateran Palace, the home of the pope. At that time, statues of two small men stood under the wolf, personifying the alliance between the Romans and their former enemies from central Italy, the Sabines. But in the later Middle Ages, people mistook the figures for children and identified the sculpture with the founding of Rome. During the Renaissance, Romans wanted more specific imagery and added the twins we see here. Pope Sixtus IV (papacy 1471–84 CE) had the sculpture moved from his palace to the Capitoline Hill. Today, the She-Wolf maintains her wary pose in a museum there. 6-1. She-Wolf. c. 500 BCE. Bronze, glass-paste eyes, height 331冫2 – (85 cm). Museo Capitolino, Rome. 181 700 ▼ 500 ▼ BCE 300 BCE ▼ BCE ▲ c. 509–27 ROMAN REPUBLIC ▲ c. 700–509 ETRUSCAN SUPREMACY ▲ 264–146 PUNIC WARS ▲ c. 450–320 CLASSICAL GREEK CULTURE ▲ c. 559–331 PERSIAN EMPIRE TIMELINE 6-1. The Etruscan and Roman Worlds. The Etruscans controlled the Italian peninsula until the Romans defeated them in 509 BCE. Roman kings unified Italy during their nearly 500-year reign. The emperors, beginning with Augustus in 27 BCE, first expanded the Roman Empire until it extended to Britain, then saw it contract until it weakened and was permanently split in 395 CE. Tiber R. NORTH SCOTLAND OCEAN SEA ATLANTIC Tarquinia Veii Cerveteri Ostia Rome C SEA Pompeii Mildenhall TYRRHENIAN eR R hi n English Channel ne Paris Trier 0 50 IONIAN 100 Miles R . . SEA Dan u FRANCE Nîmes Orange S L PMilan Venice Po R. 100 Kilometers BLACK SEA AL Populonia 50 DACIA ITALY RI A SPAIN A 0 be R . D Rh ô R. ne Gard R. ET R U PO RT UG AL SEA GERMANY . Se i Loire R Mt. Vesuvius Boscoreale Naples BA BRITAIN SEA Palestrina L TI Hadrian’s Wall ADRIATIC Tivoli Split M AT PerugiaA IA Tiber R. DR IA T A L G E R IA E Timgad A N CRETE Knossos CYPRUS 250 500 Miles 500 Kilometers Jerusalem PERSIA Ni le R. R ED S EA 0 250 R. SYRIA Cairo Fayum EGYPT 0 MESOP OTA Euphra MI tes A PALESTINE Canopus Alexandria N Tigr is PHOENICIA S E A A F R I C A M I NOR R. IC Rome Constantinople SE ASIA A MACEDONIA Naples LATIUM Nicomedia Herculaneum CAMPANIA Thessaloniki Troy TURKEY TYRRHENIAN GREECE Pergamon SEA M E D ANATOLIA I T Corinth Miletos E R See inset Athens Olympia R Carthage A Sparta N Map 6-1. The Roman Republic and Empire. After defeating the Etruscans in 509 BCE, Rome became a republic. It reached its greatest area by the time of Julius Caesar’s death in 46 BCE. The Roman Empire began in 27 BCE, extended its borders from the Euphrates River to Scotland under Trajan in 106 CE, but was permanently split into the Eastern and Western Empires in 395 CE. The boot-shaped Italian peninsula, shielded to the north by the Alps, juts into the Mediterranean Sea. At the end of the Bronze Age (about 1000 BCE), a central European people known as the Villanovans occupied the northern and western regions of Italy, and central Italy was home to a variety of people who spoke a closely related group of Italic languages, Latin among them. Beginning about 750 BCE, Greeks too established colonies in Italy and in Sicily. Between the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, the people known as the Etruscans, probably related to the Vil- ETRUSCAN CIVILIZATION 182 CHAPTER 6 Etruscan Art and Roman Art lanovans, gained control of northern and much of central Italy, an area known as Etruria (modern Tuscany). The Etruscans’ wealth came from Etruria’s fertile soil and abundance of metal ore. Noted as both farmers and metalworkers, the Etruscans were also sailors and merchants, and they exploited their resources in trade with the Greeks and with the people of Phoenicia (modern Lebanon). Although Etruscan artists knew and drew inspiration from Greek and Near Eastern sources, they never slavishly copied what they admired. Instead, they assimilated these influences and created a distinctive Etruscan style. Organized into a loose federation of a dozen cities, ARCH, VAULT, AND DOME The first true arch used in Western architecture is the round arch. When extended, the round arch becomes a barrel vault. The round arch and barrel vault were known and were put to limited use by Mesopotamians and Egyptians long before the Etruscans began their experiments. But it was the Romans who realized the potential strength and versatility of these architectural features and exploited them to the fullest degree. The round arch displaces most of the weight, or downward thrust (see arrows on diagrams), of the masonry above it to its curving sides and transmits that weight to the supporting uprights (door or window jambs, columns, or piers), and from there to the ground. Arches may require added support, called buttressing, from adjacent masonry elements. Brick or cut-stone arches are formed by fitting together wedgeshaped pieces, called voussoirs, until they meet and are locked together at the top center by the final piece, called the keystone. Until the mortar between the bricks or stones dries, an arch is held in place by wooden scaffolding, called centering. The inside surface of the arch is called the intrados, the outside curve of the arch the extrados. The points from which the curves of the arch rise, called springings, are often reinforced by masonry imposts. The wall areas adjacent to the curves of the arch are spandrels. In a succession of arches, called an arcade, the space encompassed by each arch and its supports is called a bay. The barrel vault is constructed in the same manner as the round arch. The outside pressure exerted by the curving sides of the barrel vault requires buttressing within or outside the supporting walls. When two barrelvaulted spaces intersect each other at the same level, the result is a groin vault. The Romans used the groin vault to construct some of their grandest interior spaces, and they made the round arch the basis for their great freestanding triumphal arches. A third type of vault brought to technical perfection by the Romans is the hemispheric dome. The rim of the dome is supported on a circular wall, as in the Pantheon (see figs. 6-46, 6-47). This wall is called a drum when it is raised on top of a main structure. Sometimes a circular opening, called an oculus, is left at the top. keystone spandrel spandrel extrados voussoirs intrados springing impost centering jamb piers bay round arch buttress buttress barrel vault 186 CHAPTER 6 Etruscan Art and Roman Art space included in bay piers groin vault 6-28. Atrium, House of the Silver Wedding, Pompeii. Early 1st century CE Ancient Roman houses excavated at Pompeii and elsewhere are usually simply given numbers by archaeologists or (if known) named after the families or individuals who once lived in them. This house received its unusual name as a commemorative gesture. It was excavated in 1893, the year of the silver wedding anniversary of Italy’s King Humbert and his wife, Margaret of Savoy, who had supported archaeological fieldwork at Pompeii. mild southern climate permitted gardens to flourish year-round, the peristyle was often turned into an outdoor living room with painted walls, fountains, and sculpture, as in the mid-first-century CE House of the Vettii (fig. 6-29, page 206). WALL PAINTING Many fine wall paintings have come to light through excavations, first in Pompeii and other communities surrounding Mount Vesuvius, near Naples, and more recently in and around Rome. The interior walls of Roman houses were plain, smooth plaster surfaces with few architectural features. On these invitingly empty spaces, artists painted decorations using pigment in a solution of lime and soap, sometimes with a little wax. After the painting was finished, they polished it with a special metal, glass, or stone burnisher and then buffed the surface with a cloth. In the earliest paintings (200–80 BCE), artists attempted to produce the illusion of thin slabs of colored marble covering the walls, which were set off by actual architectural moldings and columns. By about 80 BCE, they began to extend the space of a room visually with painted scenes of figures on a shallow “stage” or with a landscape or cityscape. Architectural details such as columns were painted rather than made of molded plaster. As time passed, this painted architecture became increasingly fanciful. Solid-colored walls were decorated with slender, whimsical architectural and floral details and small, delicate vignettes. The walls of a room from a villa at Boscoreale near Pompeii (reconstructed in The Metropolitan Museum, New York) open onto a fantastic urban panorama (fig. 6-30, page 206). The wall surfaces seem to dissolve behind columns and lintels, which frame a maze of floating architectural forms creating purely visual effects, like the CHAPTER 6 Etruscan Art and Roman Art 205 6-29. Peristyle garden, House of the Vettii, Pompeii. 2nd century BCE, rebuilt 60–79 BCE 6-30. Reconstructed bedroom, from the House of Publius Fannius Synistor, Boscoreale, near Pompeii. Late 1st century CE, with later furnishings. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1903 (03.14.13) Although the elements in the room are from a variety of places and dates, they give a sense of how the original furnished room might have looked. The floor mosaic, found near Rome, dates to the second century CE. At its center is an image of a priest offering a basket with a snake to a cult image of Isis. The couch and footstool, which are inlaid with bone and glass, date from the first century CE. The wall paintings, original to the Boscoreale villa, may have been inspired by theater scene painting. 206 CHAPTER 6 Etruscan Art and Roman Art THE URBAN GARDEN The remains of urban gardens preserved in the volcanic fallout at Pompeii have been the focus of a decades-long study by archaeologist Wilhelmina Jashemski. Her work has revealed much about the layout of ancient Roman gardens and the plants cultivated in them. Early archaeologists, searching for more tangible remains, usually destroyed evidence of gardens, but in 1973 Jashemski and her colleagues had the opportunity to work on the previously undisturbed peristyle garden—a planted interior court enclosed by columns—of the House of G. Polybius in Pompeii. Workers first removed layers of debris and volcanic material to expose the level of the soil as it was before the eruption in 79 CE. They then collected samples of pollen, seeds, and other organic material and carefully injected plaster into underground root cavities to make casts for later study. These materials enabled botanists to identify the types of plants and trees cultivated in the garden, to estimate their size, and to determine where they had been planted. The evidence from this and other excavations indicates that most urban gardens served a practical function. They were planted with fruit- and nut-bearing trees and occasionally with olive trees. Only the great luxury gardens were rigidly landscaped. Most gardens were randomly planted or, at best, arranged in irregular rows. Some houses had both peristyle gardens and separate vegetable gardens. The garden in the house of Polybius was surrounded on three sides by a portico, which protected a large cistern on one side that supplied the house and garden with water. Young lemon trees in pots lined the fourth side of the garden, and nail holes in the wall above the pots indicated that the trees had been espaliered—pruned and trained to grow flat against a support—a practice still in use today. Fig, cherry, and pear trees filled the garden space, and traces of a fruitpicking ladder, wide at the bottom and narrow at the top to fit among Wall niche, from a garden in Pompeii Mid-1st century CE. Mosaic, 433冫4 * 311冫2 – (111 * 80 cm). Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, England. the branches, was found on the site. This evidence suggests that the garden was a densely planted orchard similar to the one painted on the dining-room walls of the villa of Empress Livia in Primaporta (see fig. 6-32). An aqueduct built during the reign of Augustus had given Pompeii’s residents access to a reliable and plentiful supply of water, eliminating their dependence on wells and rainwater basins and allowing them to add to their gardens pools, fountains, and flowering plants that needed heavy watering. In contrast to the earlier, unordered plantings, formal gardens with low, clipped borders and plantings of ivy, orna- mental boxwood, laurel, myrtle, acanthus, and rosemary—all mentioned by writers of the time— became fashionable. There is also evidence of topiary work, the clipping of shrubs and hedges into fanciful shapes. Sculpture and purely decorative fountains became popular. The peristyle garden of the House of the Vettii, for example, had more than a dozen fountain statues jetting water into marble basins (see fig. 6-29). In the most elegant peristyles, mosaic decorations covered the floors, walls, and even the fountains. Some of the earliest wall mosaics, such as the one illustrated here, were created as backdrops for fountains. CHAPTER 6 Etruscan Art and Roman Art 207 6-31. Cityscape, detail of a wall painting from a bedroom in the House of Publius Fannius Synistor, Boscoreale. Late 1st century CE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1903 (03.14.13) backdrops of a stage. Indeed, the theater may have inspired this kind of decoration, as details in the room suggest. For example, on the rear wall, next to the window, is a painting of a grotto, the traditional setting for satyr plays, dramatic interludes about the half-man, half-goat followers of Bacchus. On the side walls, paintings of theatrical masks hang from the lintels. One section shows a complex jumble of buildings with balconies, windows, arcades, and roofs at different levels, as well as a magnificent colonnade (fig. 6-31). The artist has used intuitive perspective admirably to create a general impression of real space. The architectural details follow diagonal lines that the eye interprets as parallel lines receding into the distance, and objects meant to be perceived as far away from the surface plane of the wall are shown slightly smaller than those intended to appear nearby. The dining-room walls of the Villa of Livia at Primaporta exemplify yet another approach to creating a sense of expanded space (fig. 6-32). Instead of rendering a stage set or a cityscape, the artist “painted away” the wall surfaces to create the illusion of being on a porch or pavilion looking out over a low, paneled wall into an orchard of heavily laden fruit trees. These and the flowering shrubs are filled with a variety of wonderfully observed birds. During the first century CE, landscape painters became especially accomplished. Pliny the Elder wrote in Naturalis Historia (35.116–17) of that most delightful technique of painting walls with representations of villas, porticoes and landscape gardens, woods, groves, hills, pools, channels, rivers, coastlines—in fact, every sort of thing which one might want, and also various representations of people within them walking or sailing . . . and also fishing, fowling, or hunting or even harvesting the wine-grapes. 6-32. Garden Scene, detail of a wall painting from the Villa of Livia at Primaporta, near Rome. Late 1st century BCE. Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome. 208 CHAPTER 6 Etruscan Art and Roman Art 6-33. Seascape, detail of a wall painting from Villa Farnesina, Rome. Late 1st century CE 6-34. Initiation Rites of the Cult of Bacchus (?), detail of a wall painting in the Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii. c. 50 BCE In such paintings, the overall effect is one of wonderinvoking nature, an idealized view of the world, rendered with free, fluid brushwork and delicate color. A painting from the Villa Farnesina, in Rome (fig. 6-33), depicts the locus amoenus, the “lovely place” extolled by Roman poets, where people lived effortlessly in union with the land. Here two conventions create the illusion of space: distant objects are rendered proportionally smaller than near objects, and the colors become slightly grayer near the horizon, an effect called atmospheric perspective, which reproduces the ten- dency of distant objects to appear hazy, especially in seascapes. In addition to landscapes and city views, other subjects that appeared in Roman art included historical and mythological scenes, exquisitely rendered still lifes (compositions of inanimate objects), and portraits. One of the most famous painted rooms in Roman art is in the so-called Villa of the Mysteries at Pompeii (fig. 6-34). The rites of mystery religions were often performed in private homes as well as in special buildings or temples, and this room, at the corner of a suburban villa, must CHAPTER 6 Etruscan Art and Roman Art 209 6-35. Still Life, detail of a wall painting from Herculaneum. 6-36. Young Woman Writing, detail of a wall painting, c. 62–69 CE. Museo Nazionale, Naples. from Pompeii. Late 1st century CE. Diameter 145冫8 – (37 cm). Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. have been a shrine or meeting place for such a cult. A reminder of the wide variety of religious practices tolerated by the Romans, the murals depict initiation rites— probably into the cult of Bacchus, who was the god of vegetation and fertility as well as wine and was one of the most important deities in Pompeii. The entirely painted architectural setting consists of a “marble” dado (the lower part of a wall) and, around the top of the wall, an elegant frieze supported by pilasters. The action takes place on a shallow “stage” along the top of the dado, with a background of brilliant, deep red (now known as Pompeian red) that was very popular with Roman painters. The scene unfolds around the entire room, depicting a succession of events that culminate in the acceptance of an initiate into the cult. In the portion of the room seen here, a priestess (on the left) prepares to reveal draped cult objects, a female initiate lies across the lap of another woman, and a devotee dances with cymbals, perhaps to drown out the initiate’s cries. A fourth female figure carries a long rod. According to another interpretation, the dancing figure is the initiate herself, who has risen to dance with joy at the conclusion of her trials. The whole scene may show a purification ritual meant to bring enlightenment and blissful union with the god. Wall painting also depicted more mundane subject matter. A still-life panel from Herculaneum, a community in the vicinity of Mount Vesuvius near Pompeii, depicts everyday domestic objects—still-green peaches just picked from the tree and a glass jar half filled with water (fig. 6-35). The items have been carefully arranged on two shelves to give the composition clarity and balance. A strong, clear light floods the picture from right to left, casting shadows, picking up highlights, and enhancing the illusion of real objects in real space. 210 CHAPTER 6 Etruscan Art and Roman Art The fashionable young woman seems to be pondering what she will write about with her stylus on the beribboned writing tablet that she holds in her other hand. Romans used pointed styluses to engrave letters on thin, wax-coated ivory or wood tablets in much the way we might use a hand-held computer; errors could be easily smoothed over. When a text or letter was considered ready, it was copied onto expensive papyrus or parchment. Tablets like these were also used by schoolchildren for their homework. Portraits, sometimes imaginary ones, also became popular. A late-first-century CE tondo (circular panel) from Pompeii contains the portrait Young Woman Writing (fig. 6-36). The sitter has regular features and curly hair caught in a golden net. As in a modern studio portrait photograph with its careful lighting and retouching, the young woman may be somewhat idealized. Following a popular convention, she nibbles on the tip of her stylus. Her sweet mien and clear-eyed but unfocused and contemplative gaze suggest that she is in the throes of composition. The paintings in Pompeii reveal much about the lives of women during this period (see “The Position of Roman Women,” page 235). Some, like Julia Felix, were the owners of houses where paintings were found. Others were the subjects of the paintings, shown as rich and poor, young and old, employed as business managers and domestic workers. Just as architecture became increasingly grand, even grandiose, during the first 150 years of the Roman Empire, so, too, did the decorative wall painting in houses become ever more elaborate. In the House of M. Lucretius Fronto in Pompeii, from the mid-first century CE (fig. 6-37), the artist painted a room with panels of black and red, bordered with architectural moldings. These architectural elements have no logic, and for all their playing with perspective, they fail to create any significant