Terms of reference for training needs analysis

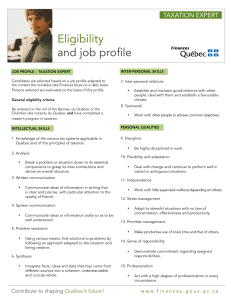

advertisement