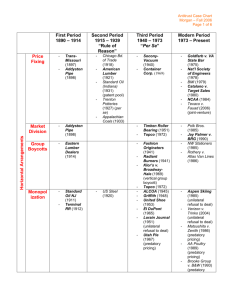

Barriers to Entry and Exit in European Competition

advertisement