Competition Research Paper

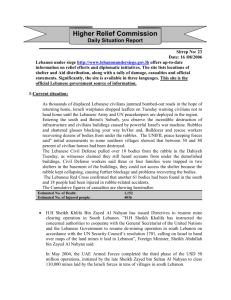

advertisement