Chronic Avoidance Helps Explain

the Relationship Between Severity

of Childhood Sexual Abuse

and Psychological Distress in Adulthood

M. Zachary Rosenthal

Mandra L. Rasmussen Hall

Kathleen M. Palm

Sonja V. Batten

Victoria M. Follette

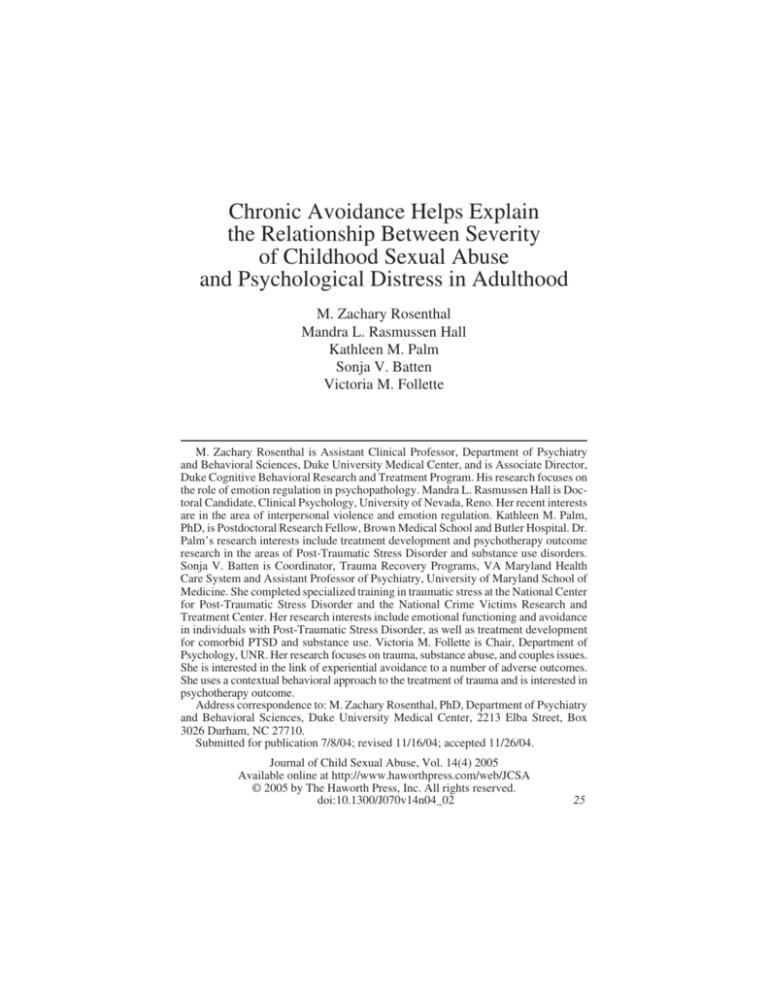

M. Zachary Rosenthal is Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Psychiatry

and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, and is Associate Director,

Duke Cognitive Behavioral Research and Treatment Program. His research focuses on

the role of emotion regulation in psychopathology. Mandra L. Rasmussen Hall is Doctoral Candidate, Clinical Psychology, University of Nevada, Reno. Her recent interests

are in the area of interpersonal violence and emotion regulation. Kathleen M. Palm,

PhD, is Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Brown Medical School and Butler Hospital. Dr.

Palm’s research interests include treatment development and psychotherapy outcome

research in the areas of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and substance use disorders.

Sonja V. Batten is Coordinator, Trauma Recovery Programs, VA Maryland Health

Care System and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of

Medicine. She completed specialized training in traumatic stress at the National Center

for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and the National Crime Victims Research and

Treatment Center. Her research interests include emotional functioning and avoidance

in individuals with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, as well as treatment development

for comorbid PTSD and substance use. Victoria M. Follette is Chair, Department of

Psychology, UNR. Her research focuses on trauma, substance abuse, and couples issues.

She is interested in the link of experiential avoidance to a number of adverse outcomes.

She uses a contextual behavioral approach to the treatment of trauma and is interested in

psychotherapy outcome.

Address correspondence to: M. Zachary Rosenthal, PhD, Department of Psychiatry

and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, 2213 Elba Street, Box

3026 Durham, NC 27710.

Submitted for publication 7/8/04; revised 11/16/04; accepted 11/26/04.

Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, Vol. 14(4) 2005

Available online at http://www.haworthpress.com/web/JCSA

© 2005 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1300/J070v14n04_02

25

26

JOURNAL OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE

ABSTRACT. Recent studies have found that chronic avoidance of unpleasant internal experiences (e.g., thoughts, emotions, memories) is a

maladaptive means of affect regulation often adopted by women with a

history of sexual victimization in childhood. The primary aim of this study

was to replicate and extend previous findings suggesting that higher levels

of experiential avoidance may account for the relationship between childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and psychological distress in adulthood. It was

hypothesized that, in a sample of undergraduate females (n = 151), the relationship between severity of CSA (e.g., frequency, nature of victimization)

and trauma-related psychological distress would be mediated by avoidance.

Results supported this hypothesis. Findings are consistent with previous studies, and further suggest that the general tendency to avoid or escape from unpleasant internal experiences may be a specific factor that exacerbates

psychological distress among women with a history of sexual victimization in

childhood. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery

Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <docdelivery@haworthpress.com>

Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2005 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All

rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. Childhood sexual abuse, psychological distress, emotion regulation, avoidance, coping

Sexual victimization during childhood is associated with a wide range of

adverse outcomes, including psychological distress, depression, anxiety,

substance abuse, suicidal behavior, and borderline personality disorder (for

reviews, see Browne & Finkelhor, 1986; Polusny & Follette, 1995). However, the relationship between childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and negative

outcomes in adulthood is correlational and complex. Recently, researchers

have begun to examine mediational models hypothesized to help account

for this relationship, in order to understand how psychopathology develops

following CSA.

The tendency to deliberately avoid or escape from unpleasant internal experiences (e.g., thoughts, feelings, sensations), or experiential

avoidance, has been reported in preliminary studies with undergraduate

females to mediate the relationship between sexual victimization before

the age of 18 and psychological functioning in adulthood (Marx &

Sloan, 2002; Polusny, Rosenthal, Aban, & Follette, 2004). Similarly,

avoidant coping has been shown to mediate the relationship between a

history of sexual abuse and symptoms of traumatic stress in a large sam-

Rosenthal et al.

27

ple of Belgian adolescents (Bal, Van Oost, De Bourdeaudhuij, & Crombez, 2003). Despite these studies, the inter-relationships among severity

of CSA (e.g., frequency, nature of victimization), avoidance, and psychological distress have yet to be examined. The two main purposes of this

study are to: (a) replicate findings from previous studies indicating that

chronic avoidance is associated with a self-reported history of CSA, and

(b) extend previous studies by examining a mediational model that specifically tests the extent to which avoidance accounts for the relationship

between severity of CSA and trauma-related psychological distress.

SEXUAL VICTIMIZATION IN CHILDHOOD

Epidemiological studies suggest that approximately 15% to 32% of

women in the United States report a history of CSA (e.g., Vogeltanz,

Wilsnack, Harris, Wilsnack, Wonderlich, & Kristjanson, 1999). Over

the past 20 years, researchers have documented the link between CSA

and psychological maladjustment. However, a handful of studies, including an influential meta-analysis, have found that the relationship

between CSA and adverse outcomes may be modest (Rind, Tromovitch, & Bauserman, 1998), and may be explained, in part, by other

variables such as one’s family environment (Nash, Hulsey, Sexton,

Harralson, & Lambert, 1993) or use of maladaptive coping strategies

(e.g., Merrill, Guimond, Thomsen, & Milner, 2003; Runtz & Schallow,

1997).

Many studies examining the impact of CSA on psychopathology

have compared those with to those without a history of CSA. Fewer

studies have examined the relationship between the severity of CSA and

negative outcomes. This is noteworthy, as definitions of CSA vary

across studies, with different criteria for the nature of the abusive experiences (e.g., non-contact experiences or sexual contact) used. Although

there currently is no standard measure of CSA severity, some researchers have created indices of severity based on reported characteristics of

one’s CSA history. For example, Zanarini and colleagues (2002) developed a system for calculating the estimated severity of CSA. Abuse specific information was collected (e.g., relationship to the perpetrator,

whether force was used, the nature of the abuse, the frequency of the

abusive incidents, etc.) and rated, such that more severe abuse received

a higher score (e.g., force = 1, no force = 0). Severity of abuse was calculated by summing the total score of all severity domains. For the pur-

28

JOURNAL OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE

pose of the present study, the Zanarini et al. (2002) severity index was

adopted as a useful way of integrating abuse-specific severity factors

into a composite variable.

Avoidance

Defined as “the phenomenon that occurs when a person is unwilling

to remain in contact with particular private experiences (e.g., bodily

sensations, emotions, thoughts, memories, behavioral predispositions)

and takes steps to alter the form or frequency of these events and the

contexts that occasion them” (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, &

Strosahl, 1996, p. 1154), chronic experiential avoidance is one way to

conceptualize the range of maladaptive behaviors observed in some survivors of sexual trauma (Polusny & Follette, 1995). Greater use of

avoidance has been associated with psychopathology, including anxiety

(Craske & Hazlett-Stevens, 2002), depressive symptoms (Polusny et

al., 2004), severity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptomatology (Boeschen, Koss, Figueredo, & Coan, 2001), substance abuse

(Stasiewicz & Maisto, 1993), greater psychological distress (Marx &

Sloan, 2002), and poorer clinical outcomes (e.g., Hayes et al., 1996;

Roemer, Litz, Orsillo, & Wagner, 2001).

In Polusny and Follette’s (1995) model of the long-term correlates of

CSA, experiential avoidance is hypothesized to mediate the influence of

sexual abuse experiences on later psychological adjustment. Sexual

abuse survivors may engage in behavioral strategies (e.g., worrying,

dissociating, consuming alcohol, binge-purge eating, or self-harming

behaviors) that function to reduce or avoid unpleasant emotions or

thoughts associated with sexual abuse experiences. Although such

avoidance behaviors may provide some initial reduction in distress, attempts to avoid or eliminate aversive experiences can become excessive

and result in social isolation, depression, psychological distress, substance abuse problems, or other forms of psychopathology (Hayes et al.,

1996; Polusny & Follette, 1995).

Recent evidence also suggests the possibility that constructs similar to

experiential avoidance may be causally related to psychological distress.

In a series of recent studies, Lynch, Cheavens, Rosenthal, and Morse (in

press), have reported that greater inhibition of emotional experience via

thought suppression mediates the relationship between (a) negative affect and psychological distress in both undergraduate and clinical samples (Lynch, Robins, Mendelson, & Krause, 2001), (b) childhood maltreatment and adult psychological distress in a non-clinical sample

Rosenthal et al.

29

(Krause, Mendelson, & Lynch, 2003; Rosenthal, Polusny, & Follette, in

press), (c) negative affectivity/reactivity and features of borderline personality disorder in an undergraduate sample (Cheavens et al., in press),

and (d) negative affect intensity/reactivity and higher levels of suicidal

ideation and hopelessness in a sample of depressed older adults (Lynch et

al., in press).

Research examining the coping strategies of survivors of sexual abuse

provides further support for the impact of avoidance on long-term functioning. Findings indicate that avoidant coping, such as emotional suppression, denial, detachment, self-blame, and self-isolation, may result in

more impaired functioning than coping involving disclosure and support-seeking behavior (for a review, see Spaccarelli, 1994). More specifically, recent studies offer support for avoidance as an important factor in

the relationship between interpersonal trauma and psychological distress.

Batten, Follette, and Aban (2001), found that college women who reported a history of CSA scored significantly higher on measures of experiential avoidance and reported greater high-risk sexual behavior than

women without a history of CSA. A study examining experiential avoidance in adult rape survivors found that cognitive avoidance or “blocking”

of rape-related thoughts had small but detrimental effects on post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms (Boeschen, Koss, Figueredo, & Coan,

2001). Another study found that undergraduate women who reported

CSA only or both CSA and adult sexual assault showed significantly

greater use of “escapism” as a coping strategy than women who reported

no trauma (Proulx, Koverola, Fedorowicz, & Kral, 1995).

Two studies testing mediational models of sexual victimization, experiential avoidance, and psychological distress in undergraduate

women have recently been reported. In one study, experiential avoidance fully mediated the relationship between a history of CSA and a

measure of global psychological distress (Marx & Sloan, 2002). In the

other study, Polusny et al. (2004), reported that experiential avoidance

partially mediated the relationship between adolescent sexual assault

(attempted or completed sexual assault between the ages of 14 and 18)

and both psychological distress and depressive symptoms. Overall,

there appears to be emerging evidence that the chronic use of avoidance

as a means of regulating unpleasant cognitions and emotion may play an

important role in the maintenance of psychological distress. However,

to date, no studies have examined whether avoidance accounts for the

relationship between greater severity of CSA and greater trauma-related psychological distress.

30

JOURNAL OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE

Current Study

In line with theoretical predictions (Polusny & Follette, 1995) and

previous findings (Marx & Sloan, 2002; Polusny et al., 2004), the current study utilized a sample of undergraduate women (n = 151) to investigate the extent to which the self-reported severity of sexually abusive

experiences during childhood is associated with higher avoidance and

trauma-related psychological distress. Specifically, we hypothesized

that greater self-reported use of avoidance would be a regulation strategy associated with greater psychological distress, and that avoidance

would mediate the relationship between psychological distress and the

severity of CSA.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 153 female undergraduate students enrolled in psychology courses at a medium-sized western university. All participants

were recruited through undergraduate psychology courses and were eligible to participate if they were female, at least 18 years old, and primarily English speaking. Females were specifically recruited in order to

replicate previous studies examining the role of avoidance among

women with a history of CSA. Two participants were identified as outliers (z > 3.29) on the dependent measure, and were excluded from data

analyses. Thus, the final sample included 151 undergraduate females.

Participation was voluntary and all participants received extra credit as

compensation. The mean age of participants was 21.0 years (SD = 6.1;

range = 18-57), and the majority of participants were Caucasian

(81.5%) and unmarried (93.3%).

Measures

Demographics. Standard demographic variables were assessed, including age, ethnicity, and marital status.

Sexual Victimization. Sexually abusive experiences during childhood were assessed using behaviorally specific, self-report items derived from the Wyatt Sexual History Questionnaire (WSHQ; Wyatt,

1988; Wyatt, Lawrence, Vodounon, & Mickey, 1992). Items ranged

from fondling to completed vaginal, oral, or anal intercourse, and par-

Rosenthal et al.

31

ticipants responded to the items dichotomously (yes = 1 or no = 0). CSA

was defined as endorsement of at least one form of sexual contact, ranging from fondling to completed vaginal, oral, or anal intercourse, that

occurred prior to age 14 by someone at least five years older than the

participant, or of any age if the contact was not desired or involved coercion (Wyatt et al., 1992). Other items assessed abuse-specific factors

associated with severity of abuse. The specific severity domains are

presented in Table 1, along with the severity of CSA index outlined by

Zanarini et al. (2002). The combination of these factors was used in order to comprehensively include a range of CSA characteristics as an index of severity.

Avoidance. The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ;

Bond & Bunce, 2003; Hayes et al., in press) is a 16-item self-report instrument designed to measure psychological acceptance, emotional

willingness, and the tendency to engage in emotional avoidance. Each

TABLE 1. Domains of Self-reported Sexual Victimization Experiences During

Childhood

Points

N

%

Age of Abuse

Early Childhood (0-9)

Late Childhood (10-13)

Both

1 pt

2 pts

3 pts

29

14

7

19.2

9.3

4.6

Frequency

Once

Several times yearly or less

Monthly or Daily

1 pt

2 pts

3 pts

19

23

8

12.6

15.2

5.3

Duration

1 Month or less

>1 Month, < 1 year

1 Year or more

1 pt

2 pts

3 pts

22

9

18

14.6

6.0

11.9

Relationship to perpetrator

Stranger

Know abuser

Caretaker

1 pt

2 pts

3 pts

8

38

4

5.3

25.2

2.6

Nature of victimization

Observation without contact

Fondling

Penetration (Oral/Anal/Vaginal)

1 pt

2 pts

3 pts

14

27

8

9.3

17.9

5.3

Force used

Yes

1 pt

13

8.6

Life threatened

Yes

1 pt

2

1.3

32

JOURNAL OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE

item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = never true to 7 = always

true), and higher scores indicate greater acceptance (as opposed to

avoidance). Sample items include “I try hard to avoid feeling depressed

or anxious” (reverse scored) and “I rarely worry about getting my anxieties, worries, and feelings under control.” Preliminary data support the

reliability and validity of the 16-item AAQ, and higher scores on the

AAQ have been associated with greater psychopathology and distress

(Hayes et al., in press). Recent analysis of the 16-item AAQ indicates an

internal consistency reliability coefficient of .71 (Bond & Bunce, 2003)

and a two-factor structure: (a) willingness to experience internal events

and (b) ability to take action, even in the face of unwanted internal

events.

The Impact of Event Scale (IES; Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979)

is a 15-item self-report measure of traumatic stress symptoms. Each

item is rated on a four-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 4 = often). The

IES has two stable factors (Intrusion and Avoidance) that form separate

subscales (Sundin & Horowitz, 2002). The IES Avoidance Subscale

(IES-A) was used in this study as a measure of avoidant reactions and

behaviors (e.g., thought suppression and behavioral inhibition). Sample

items include, “I tried not to think about it” and “I stayed away from reminders of it.” The IES has good internal consistency and test-retest reliability, as well as discriminant and convergent validity (Horowitz et

al., 1979; Sundin & Horowitz, 2002).

Psychological distress. The Trauma Symptom Inventory (TSI; Briere,

Elliot, Harris, & Cotman, 1995) is a 104-item self-report instrument designed to assess symptoms related to traumatic stress. Participants responded to each item of the TSI without having to make reference to a

specific traumatic event. The TSI has nine subscales measuring various

aspects of trauma-related symptoms, and higher scores on each subscale

indicate higher levels of symptomatology. The mean internal consistency

alpha for the TSI has been reported as .87 (Briere et al., 1995). The total

TSI score was used as the global measure of psychological distress in this

study.

Procedure

Upon arriving at the laboratory, each participant was greeted by a research assistant and given time to read and sign a consent form. The research assistant answered questions, and then described the study in a

scripted manner. Each participant was told that the study was designed

to identify ways in which women cope with stressful life experiences.

Rosenthal et al.

33

RESULTS

The first step in the data analytic plan was to examine the distribution

of the data to evaluate the influence of potential outliers, skewness, and

kurtosis. All variables were normally distributed. Because the avoidance

measures (AAQ and IES-A) are scaled differently, a z-score composite

variable was computed for the avoidance variable used in all analyses.

Next, bivariate correlations and independent samples t-tests were conducted in order to examine the inter-relationships among variables and

determine whether participants with a history of CSA reported higher

levels of avoidance and psychological distress than participants who denied a history of CSA.

The multiple regression strategy outlined by Baron and Kenny

(1986) and Holmbeck (1997) was used to test avoidance as a mediator

in the relationship between severity of CSA and psychological distress.

According to Baron and Kenny, four statistical criteria must be met to

establish a variable as a mediator, and these four conditions can be

tested using a series of regression analyses (Holmbeck, 1997). First,

there must be a significant relationship between the predictor variable

(severity of CSA) and the mediator (avoidance). Second, a significant

relationship must be established between the predictor and the dependent variable (psychological distress). Third, the mediator must be significantly related to the dependent variable. Fourth, the relationship

between the predictor and the dependent variable must be significantly

reduced when the mediator is added to the regression equation. Sobel’s

(1982) formula was used to test whether the association between severity of CSA and psychological distress was significantly reduced after

adding avoidance to the regression equation. In order to reduce the

probability of committing a Type I error, a Bonferroni-correction procedure was used whereby .05 was divided by the number of tests. Thus,

the alpha level was set at .008.

Bivariate Correlations and t-Tests

The bivariate correlations among the variables are presented in Table 2. Of the eight Pearson correlations, all but one were significant at

the p < .008 level. The relationship between severity of CSA and one

measure of avoidance (IES-A) approached significance (p = .009). Two

independent samples t-tests were conducted using CSA status (0 = no;

1 = yes) as a between groups variable. As hypothesized, compared to

participants with no reported history of CSA, those who reported a his-

34

JOURNAL OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE

TABLE 2. Pearson Correlation Coefficients Among All Variables

Measure

1

1. CSA-Sev

2. IES-A

3. AAQ

4. AVD-Z

2

3

4

5

.22

.30*

.33*

.34*

.37*

N/A

.48*

N/A

.59*

.64*

5. TSI

*p < .008

Note: CSA-Sev = Severity of childhood sexual abuse; IES-A = Impact of Events-Avoidance

Scale; AAQ = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire total score; AVD-Z = Avoidance z-score;

TSI = Trauma Symptom Inventory total score; N/A = Not Applicable. This notation is used because AAQ and IES-A are combined to form AVD-Z.

tory of CSA had higher scores on the TSI (no CSA M = 61.62, SD =

37.94; CSA M = 94.35, SD = 54.56; t (73.21) = 3.81, p < .008) and

avoidance z-score (no CSA M = ⫺0.48, SD = 1.43; CSA M = 0.67, SD =

1.67; t (144) = 4.33, p < .008).

Mediational Model

The first step of the mediational test involved examining the relationship between avoidance (the mediating variable) and severity of CSA

(the predictor variable). This model was significant, R2 = .11, F(1, 144) =

17.52, p < .008. Specifically, severity of CSA significantly predicted

avoidance (β = .33). Thus, the first criterion for mediation as defined by

Baron and Kenny (1986) was met.

The second step of the mediational test involved examining the relationship between avoidance (the mediating variable) and psychological

distress (the dependent variable). This model was significant, R2 = .41,

F(1, 144) = 101.34, p < .008. Specifically, avoidance significantly predicted psychological distress (β = .64). Thus, the second criterion for mediation was met.

The third step of the mediational test involved examining the relationship between severity of CSA (the predictor variable) and psychological

distress (the dependent variable). This model was significant, R2 = .12,

F(1, 149) = 19.41, p < .008. Specifically, severity of CSA significantly

predicted psychological distress (β = .34). Thus, the third criterion for mediation was met.

Rosenthal et al.

35

The final step, as described by Baron and Kenny (1986), is a test of

the relationship between the predictor variable and the dependent variable when the mediating variable is included in the model. The prediction in this case was that the magnitude of the relationship between the

severity of CSA and psychological distress would be reduced or no longer be significant when avoidance was included in the model.

To test this, psychological distress (the dependent variable) was regressed onto avoidance (the mediating variable) in the second step, after

entering severity of CSA (the predictor) in step one of the equation. The

results of this model were significant in step two, R2 = .44, F(2, 143) =

55.19, p < .008. As hypothesized, avoidance (β = .59, p < .008) remained significant over and above the effects of severity of CSA. Additionally, consistent with the prediction of mediation, severity of CSA

was no longer a significant predictor in step two (β = .16, ns).

To test the mediational effect of avoidance on the relationship between severity of CSA and psychological distress, a direct significance

test was conducted with a formula used to test the joint significance of

the pathways in this mediation (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993). This test,

which results in a z-score, was significant (z = 3.81, p < .008), indicating

that avoidance fully mediated the relationship between severity of CSA

and psychological distress.

Results of the regression analyses are shown in the path diagram in

Figure 1. The direct effect of CSA severity on psychological distress is

represented by the standardized coefficient for path C ( = .34). The indirect effect of CSA severity on psychological distress is computed by

FIGURE 1. Path Diagram of Regression Analyses (Standardized Beta Weights)

Showing Avoidance as a Mediator of the Relationship between CSA Severity

and Psychological Distress.

Avoidance

(B)

(A)

.64

.33

Psychological

Distress

CSA Severity

.34

(C)

36

JOURNAL OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE

multiplying the standardized coefficients of paths A and B that link

CSA severity to psychological distress through avoidance, = .33, =

.64 (.33 ⫻ .64 = .21). In sum, this study suggests that avoidance accounted for 21% of the total effect of CSA severity on psychological

distress.

DISCUSSION

There is growing interest in avoidance as a problematic means of regulating affect among individuals who present with a variety of psychiatric problems (e.g., Bach & Hayes, 2002; Cheavens et al., in press;

Roemer & Orsillo, 2002; Rosenthal, Cheavens, Lejuez, & Lynch, in

press; Rosenthal, Cheavens, Compton, Thorp, & Lynch, in press). More

specifically, some researchers describe avoidance as an important construct that helps explain how exposure to traumatic events can lead to

subsequent problems (e.g., Batten et al., 2001; Polusny & Follette,

1995; Polusny et al., 2004). In order to treat avoidance as a maladaptive

emotion regulation style in trauma survivors, a clearer understanding of

its role in the development and maintenance of problems associated

with sexual trauma is essential. To date, empirical investigation of

avoidance and its relationship to traumatic stress is limited. However,

the current study represents one of a growing number of recent studies

examining the role of avoidance in the lives of women with a history of

sexual trauma.

In this study, the tendency to chronically avoid or escape unpleasant

internal experiences (i.e., avoidance) mediated the relationship between

severity of CSA and trauma-related psychological distress in adulthood.

Previous studies have reported the association between higher avoidance and psychological maladjustment among individuals with a history of sexual victimization (Batten et al., 2001). In addition, two

studies found that avoidance mediated the relationship between sexual

victimization and psychological distress (Marx & Sloan, 2002; Polusny

et al., 2004). These studies have important limitations. First, the interrelationships among severity of CSA, avoidance, and distress have not

been investigated. This may be due, in part, to the lack of a standard

measure of CSA severity. However, researchers recently have begun to

utilize CSA severity indices in order to more comprehensively investigate the relationship between CSA and negative outcomes (e.g., Merrill

et al., 2003; Zanarini et al., 2002). Second, previous studies testing

Rosenthal et al.

37

mediational models did not examine traumatic stress symptoms, and instead used measures of global psychological maladjustment. Although

general psychological distress is one of the correlates of CSA, it is also

important to test those symptoms and behaviors that may be more specific to the effects of sexual trauma exposure. The current study extends

upon previous research by examining avoidance as a mediator between

CSA severity and traumatic stress symptoms.

Findings from this study suggest that individuals who report a history

of sexual victimization before the age of 14 may report more trauma-related symptoms of distress when avoidance is used as a primary method

of regulating aversive cognitions and emotions. Frequent attempts to

avoid or escape unpleasant internal experiences may be a particularly

common emotion regulation strategy among individuals with a history

of CSA (Batten et al., 2001). Because of shame and guilt associated

with CSA, as well as the social stigma of such experiences, it is likely

that individuals with histories of sexual trauma would attempt to escape

from or avoid memories or associated thoughts and feelings through

various means. Further, as the severity of the CSA increases, an individual may be even more motivated to block out or not experience intense

thoughts and feelings related to the trauma. Although avoidance strategies may temporarily prevent unpleasant experiences, findings from

this study suggest that when used chronically, avoidance may be a regulation style that underlies trauma-related psychological distress.

Appropriate caution should be used in interpreting these findings.

First, the results of this study cannot be generalized well beyond a

non-clinical, mostly Caucasian, university sample of women. Additional

research is needed to replicate findings from this study using ethnically

diverse and clinical samples of women with a history of sexual victimization. Furthermore, research on the mediational role of avoidance in men

with a history of CSA is warranted in order to explore the relationship between gender, distress, and avoidance. Second, the cross-sectional design

of this study does not allow conclusions to be drawn about causality. In

order to draw more robust inferences regarding the mediational role of

avoidance, prospective studies are needed. Third, sexual victimization

was reported retrospectively in this study, and it is important to note that

this type of report could be influenced by current affective states or other

unknown variables not assessed in this study. Fourth, in addition to

avoidance, there are likely other variables that play an important mediating role in the relationship between victimization and distress. Other

types of emotion regulation strategies, for example, may also contribute

to the development and maintenance of both traumatic stress symptoms

38

JOURNAL OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE

and psychopathology. Future studies should more comprehensively examine regulation processes among individuals with a history of sexual

victimization.

In addition to providing empirical support for avoidance as an important link between CSA severity and symptoms of traumatic stress in

adulthood, these findings have potential implications for treatments of

traumatic stress that target the reduction of avoidance. Recently, some

trauma researchers have identified a need for augmenting exposure

therapies with acceptance-based treatment components from Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 1999) in order to address the

complicated clinical presentations of some survivors of sexual victimization (e.g., Becker & Zayfert, 2001; Cloitre, Koenen, Cohen, & Han,

2002; Orsillo & Batten, in press; Palm & Follette, 2000). Other researchers also are recognizing the value of incorporating acceptance

into the treatment of psychopathology more generally (e.g., Koerner,

Jacobson, & Christensen, 1994; Linehan, 1993; Hayes et al., 1999).

Findings from this study are consistent with previous studies and lend

further support to the clinical hypothesis that chronic avoidance of

thoughts and emotions may be an important treatment target for some

trauma survivors. Empirical support for such clinical and theoretical observations is essential in order to support the development of efficacious

and effective treatments for those with a history of CSA.

REFERENCES

Bach, P., & Hayes, S. C. (2002). The use of acceptance and commitment therapy to prevent the rehospitalization of psychotic patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 70, 1129-1139.

Bal, S., Van Oost, P., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., & Crombez, G. (2003). Avoidant coping as

a mediator between self-reported sexual abuse and stress-related symptoms in adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27, 883-897.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in

social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations.

Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182.

Batten, S. V., Follette, V. M., & Aban, I. B. (2001). Experiential avoidance and

high-risk sexual behavior in survivors of child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual

Abuse, 10, 101-120.

Becker, C. B., & Zayfert, C. (2001). Integrating DBT-based techniques and concepts to

facilitate exposure treatment for PTSD. Cognitive & Behavioral Practice, 8, 107-122.

Rosenthal et al.

39

Boeschen, L. E., Koss, M. P., Figueredo, A. J., & Coan, J. A. (2001). Experiential

avoidance and posttraumatic stress disorder: A cognitive mediational model of rape

recovery. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 4, 211-245.

Bond, F. W., & Bunce, D. (2003). The role of acceptance and job control in mental

health, job satisfaction, and work performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88,

1057-1067.

Briere, J., Elliot, D. M., Harris, K., & Cotman, A. (1995). Trauma Symptom Inventory:

Psychometrics and association with childhood and adult victimization in clinical

samples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10, 387-401.

Browne, A., & Finkelhor, D. (1986). Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 66-77.

Cheavens, J. S., Rosenthal, M. Z., Daughters, S. D., Novak, J., Kosson, D., Lynch, T.

R., & Lejeuz, C. (in press). An analogue investigation of the relationships among

perceived parental criticism, negative affect, and borderline personality disorder

features: The role of thought suppression. Behavior Research and Therapy.

Cloitre, M., Koenen, K. C., Cohen, L. R., & Han, H. (2002). Skills training in affective

and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for

PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 70,

1067-1074.

Craske, M. G., & Hazlett-Stevens, H. (2002). Facilitating symptom reduction and behavior change in GAD: The issue of control. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9, 69-75.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach

to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 64, 11521168.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., Wilson, K. G., Bissett, R. T., Pistorello, J., Toarmino, D.

et al. (in press). Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working

model. The Psychological Record.

Holmbeck, G. N. (1997). Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the

study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric

psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 65, 599- 610.

Horowitz, M., Wilner, N., & Alvarez, W. (1979). Impact of event scale: A measure of

subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41, 209-218.

Koerner, K., Jacobson, N.S., & Christensen, A. (1994). Emotional acceptance in integrative behavioral couple therapy. In S.C. Hayes, N.S. Jacobson, V.M. Follette, &

M.J. Dougher (Eds.), Acceptance and change: Content and context in psychotherapy (pp.109-118). Reno, NV: Context, Press.

Krause, E. D., Mendelson, T., & Lynch, T. R. (2003). Childhood emotional invalidation and adult psychological distress: The mediating role of emotional inhibition.

Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 199-213.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: The Guilford Press.

40

JOURNAL OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE

Lynch, T. R., Cheavens, J. S., Morse, J. Q., & Rosenthal, M. Z. (in press). A model predicting suicidal ideation and hopelessness in depressed older adults: The impact of

emotion inhibition and affect intensity. Aging and Mental Health.

Lynch, T. R., Robins, C. J., Mendelson, J. Q., & Krause, E. D. (2001). A mediational

model relating affect intensity, emotion inhibition, and psychological distress. Behavior Therapy, 32, 519-536.

MacKinnon, D. P., & Dwyer, J. H. (1993). Estimating mediated effects in prevention

studies. Evaluation Review, 17, 144-158.

Marx, B. P., & Sloan, D. M. (2002). The role of emotion in the psychological functioning of adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Behavior Therapy, 33, 563-577.

Merrill, L. L., Guimond, J. M., Thomsen, C. J., & Milner, J. S. (2003). Child sexual

abuse and number of sexual partners in young women: The role of abuse severity,

coping style, and sexual functioning. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology,

71, 987-996.

Nash, M. R., Hulsey, T. L., Sexton, M. C., Harralson, T. L., & Lambert, W. (1993).

Long-term sequelae of childhood sexual abuse: Perceived family environment,

psychopathology, and dissociation. Journal of Clinical & Consulting Psychology, 61,

276-283.

Orsillo, S. M., & Batten, S. V. (in press). Acceptance and commitment therapy for

posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Modification.

Palm, K. M., & Follette, V. M. (2000). Counseling strategies for adult survivors of

childhood sexual abuse. Current Directions in Clinical Psychology, 11, 49-60.

Polusny, M. A., & Follette, V. M. (1995). Long-term correlates of child sexual abuse:

Theory and review of the empirical literature. Applied & Preventive Psychology, 4,

143-166.

Polusny, M. A., Rosenthal, M. Z., Aban, I., & Follette, V. M. (2004). Experiential

avoidance as a mediator of the effects of adolescent sexual victimization on adult

psychological distress. Violence and Victims, 19, 1-12.

Proulx, J., Koverola, C., Fedorowicz, A., & Kral, M. (1995). Coping strategies as predictors of distress in survivors of single and multiple sexual victimization and

nonvictimized controls. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 1464-1483.

Rind, B., Tromovitch, P., & Bauserman, R. (1998). A meta-analytic examination of assumed properties of child sexual abuse using college samples. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 22-53.

Roemer, L., & Orsillo, S. M. (2002). Expanding our conceptualization of and treatment

for generalized anxiety disorder: Integrating mindfulness/acceptance-based approaches with existing cognitive-behavioral models. Clinical Psychology: Science &

Practice, 9, 54-68.

Roemer, L., Litz, B. T., Orsillo, S. M., & Wagner, A. W. (2001). A preliminary investigation of the role of strategic withholding of emotions in PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14, 149-156.

Rosenthal, M. Z., Polusny, M. A., & Follette, V. M. (in press). Avoidance mediates the

relation between perceived criticism in the family of origin and psychological distress in adulthood. Journal of Emotional Abuse.

Rosenthal et al.

41

Rosenthal, M. Z., Cheavens, J. S., Lejuez, C. W., & Lynch, T. R. (in press). Thought

suppression mediates the relationship between negative affect and borderline personality disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy.

Rosenthal, M. Z., Cheavens, J. S., Compton, J. S., Thorp, S. R., & Lynch, T. R. (in

press). Thought suppression and treatment outcome in late-life depression. Aging

and Mental Health.

Runtz, M. G., & Schallow, J. R. (1997). Social support and coping strategies as mediators of adult adjustment following childhood maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect,

21, 211-226.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural

equation models. In S. Leinhardt (Ed.), Sociological methodology 1982 (pp. 290312). Washington, DC: American Sociological Association.

Spaccarelli, S. (1994). Stress, appraisal, and coping in child sexual abuse: A theoretical

and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 340-362.

Stasiewicz, P. R., & Maisto, S. A. (1993). Two-factor avoidance theory: The role of

negative affect in the maintenance of substance use and substance use disorder. Behavior Therapy, 24, 337-356.

Sundin, E. C., & Horowitz, M. J. (2002). Impact of Event Scale: Psychometric properties. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 205-209.

Vogeltanz, N. D., Wilsnack, S. C., Harris, T. R., Wilsnack, R. W., Wonderlich, S. A., &

Kristjanson, A. F. (1999). Prevalence and risk factors for childhood sexual abuse in

women: National survey findings. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23, 579-592.

Wyatt, G. (1988). Wyatt Sexual History Questionnaire. University of California, Los Angeles.

Wyatt, G. E., Lawrence, J., Vodounon, A., & Mickey, M. R. (1992). The Wyatt Sex

History Questionnaire: A structured interview for female sexual history taking.

Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 1, 51-68.

Zanarini, M. C., Yong, L., Frankenburg, F. R., Hennen, J., Reich, D. B., Marino, M. F.,

& Vujaniovic, A. (2002). Severity of reported childhood sexual abuse and its relationship to severity of borderline psychopathology and psychosocial impairment

among borderline inpatients. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 190, 381-387.