Paper 38 - Action Research Resources

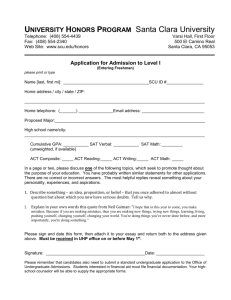

advertisement