Paul Beam, Department of English, The University of Waterloo

advertisement

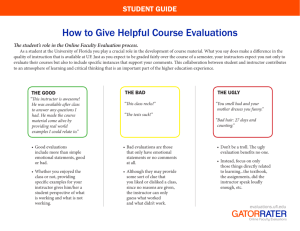

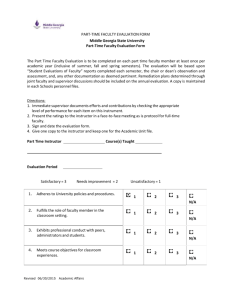

“BUT WHAT DID WE LEARN.. . ?“: EVALUATING ONLINE LEARNING AS PROCESS Paul Beam, Departmentof English, The University of Waterloo,pdbeam@watarts.uwaterloo.ca Brian Cameron,Manager of Technical Support,Information Systems& Technology, The University of Waterloo, hesse@ist.uwaterloo.ca Abstract This paper describesthe kinds of evaluation employed in the creation and managementof a credit coursein technical writing developedat the University of Waterloo. From September1995to April 1998, sections of this coursehave been offered entirely on the Web to studentsacrossCanadaat 4-month intervals. The courseusesSGML converter technology in the creation and maintenanceof its materials and in students’ preparation and submission of assignments.Evaluation includes examination of students’records of systemuse and access,assignmentpreparation and a variety of electronic communications, as well asthe electronic marking and measurementof their courseassignments.We attemptto assessgroup performance againstperceptions and to incorporate studentrequestsinto our designand expectations. In addition to the abovemethods,we presentstudentswith a seriesof optional on-line evaluationsafter significant assignmentsand at the conclusion of their final report at the end of the course. All student responsesin this processremain anonymous. Evaluation Procedures within the University Community and Their Online Variations Generally, the University of Waterloo distributes courseevaluations to studentsto obtain responseson the successof every course. Instructors distribute evaluationsto on-campus studentsduring the last scheduledclass,while distance-educationstudentsare mailed the evaluation at the end of the term. In both cases the responsesare anonymous,and the professor doesnot receive the evaluation results until after the final marks are registered.Each faculty administersa variation of the form specific to its academicneeds. Both the number and the range of the questionsare limited. For example,the distance-educationevaluation is madeup of nine questionsdealing with presentationof course material, the course’sability to maintain student imeres<the course organization, value of readings, fairness in grading, instructor feedback, and an overall evaluation of both the instructor and the course. Studentsmay respondto these questionsin the five categoriesof ‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘satisfactory’,‘fair’, and ‘poor’. In addition, there are three ‘comment’style questionsdealing with the strengthsand weaknessesof the course, and a general view of the course.In this way this form is specific to distance-educationneeds. By comparison,our online technical writing course incorporatesthe evaluation process throughout the course, allowing for a two-way dialogue to which the instructor can reacf and the studentswitness responsesto their suggestions.Insteadof a single evaluation at the end of the term, studentshave the option to completeseveralevaluations throughout the course. Theseoccur at times when their new skills and our grading of their work enablethem to understandboth their performanceand our learning objectives in light of applied instruction. In total, the studentscan respond to over one hundred questions.They receive the evaluations after eachassignmentis submitted but before the return of their gradedwork online. Such timing provides for more honestresponsesbecausethe studentsare not influenced by their assignment marks. Evaluation responsesare completely confidential. They are sent via email to a designatedcomputer account from which authorshipcannot be traced. Theseevaluationssolicit information on most aspectsof users’learning experience, participation, support and their senseof what the courseprovides, with its relevance to their expectationsabout their own training and understandingof the processesof technical documentation. We have synthesizedthe ranges of questionsfrom five faculty models and resolvedthem to the new conditions of the electronic version of the course. Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profti or commercial advantage. and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. TO COPY otherwise. to republish, to post on servers. or to redistribute to lists. requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. We have developedtheseevaluation procedures to elicit a comprehensiveview of both real activity and student opinion about their learning process. We make modifications in content, course administration and requirementsin light of the results of eachterm’s survey and we try to show studentsthe immediategood effectsof their responsesby announcing changesto proceduresand materials. Survey results from the most recent large section (120 members,55% responsesto both surveys) are provided at url: http://cito.uwaterloo.c&engl2lOe/evaluations. We usethesesametools to develop online materials for this and other coursesand we incorporate appropriatestudentmaterials, (with their permission), in new aspectsof the work. Studentscomplete five technical documentsin a sequenceof increasing complexity. They provide all other membersof the coursewith a current resume and proposal letter, from which, by a processof inquiry and selection, all membersform themselvesinto groups of three to completethe central 50% of the exercise. These documentscan be viewed at url: http//pdbeam.uwaterloo.ca/-engJ2lOe/BulletinBo ard. Thesehave given us clear evidencethat students . deemthe online learning processto be highly effective as an academicexercise l perceive it to be comprehensiveand integrated in application . seeits technology and theory as integrated into a useful set of tools for their scholarly and applied writing. They work together to produceportions of a manual, on which they then conduct usability tests. They completethe coursewith an extendedReport on an aspectof their learning experience,often related to the application of online techniquesto other areasof their training and work. Studentscreateall assignmentsin SGML.and then convert them into HTML for online display to classmatesand markers. A gradedversion of eachassignmentis returned to the studentunder a passwordfor privacy. Course Design and Structures as Background for the Evaluation Process The 4-month university coursein technical writing, which we offer entirely on the Web as credit and certificate learning through the Department of English at the University of Waterloo, is viewable at url: http://itrc.uwaterloo.caLengL!lOe . Membersare encouraged,in chats and by tutorials, to look at their own work in the contexts of others’ submissionsand the instructor’s remarks internally in their documents. Studentsretain and may distribute their materials as proof of their abilities in SGML and the creation of interactive learning. We provide referenceson students’requestto potential employers and recommendmembersto companiesseekingtechnical writers with these skills. Inquiries can be addressedto Paul Beam at pdbeam@pdbeam.uwaterloo.ca and to Brian Cameronat hesse@ist.uwaterloo.ca.Our colleague, Dr. Katherine Schellenberg, kschell@easynet.on.ca,has provided the extensive statistical planning and analysiswhich now form the basesfor our evaluation methods. By the completion of the courseeachparticipant has experiencedthe major communicationstools used in the creation and exchangeof Web-based technical documents. Eachhas worked with and understoodthe mark-up and conversion issues surrounding SGML, RTP and HTML displays. Most have dealt with someof the requirements for full multi-media expressionon CD-ROM, the Web or on Jntranetsfor internal distribution. This is ‘Technical Writing’ in a very current and completesenseand owstudents have been trained in ic individually and in groups, with all the resourcesour databasesand course layout can provide. In the near future we plan to add optional servicesin audio and video interchange, XML documentcreation and Java authoring. The course consistsof a web site with: extensive content on technical writing techniques and standards,at url: httn:Nitrc.uwaterloo.ca/-engl21Oe/Bookshelf integrated internal communication methodsemail, chat newsgroups,Instmctor Comments,online marking and the evaluation procedureswhich are the topic of this paper all available at the coursesite. the course’sdelivery engine, an SGML editor and converters,which enablestudents and instructors to createthe entire range of course content on any topic or subjectarea. 259 be developedand improved for the next large section offering. In effect, we have madea course in which the coursematerials and techniquesare learnedand usedby participants even as they completetheir writing assignments. By the conclusion of the coursemany membershave the full capacity to createSGML-basedinteractive projects for interand Intranet expressions.for their own and their employers’uses. Most coursematerials have beenavailable to the public at our web site and we continue to respondto inquiries and applications from individuals and companieson the Web. At the time of writing we are preparing a commercial version of our work, with certificate statusfor participants and an extended rangeof topics related to online learning and information exchange,to launch in fall of 1998. In September1996,we offered a vastly modified courseto a similar classsize -- 125 students acrossCanada. We had usedthe intervening months to improve the accuracy and scopeof the databaseon technical writing and the instruction materialsfor users. We still had huge problems handling, and helping studentshandle, their assignmentsubmissions. However, the changes we had madewere efficacious as studentmorale and responsesdemonstrated..Never the less,the transfer and grading processesfor assignments still exactedan unacceptableprice, in contact hours for repair and completion of student submissions,from the instructors and markers. We spentthe next eight months of 1997 addressingthe registration-privacy-submission and conversionproblems, with minimal efforts devotedto information and content issueswhich, our usersnow informed us, they deemedto be stableand complete. Getting here from nowhere: How We Built the Present Model In the fall of 1995,after a hectic eight months of development,primarily by studentswe offered the first completely Web-basedcourse in technical writing to some 120 studentsanywhere in Canadaregisteredthrough Waterloo. The project spannedfive time zones,over some3,500 miles, from Newfoundland to Vancouver. In the preceding months we’d designedand built the coursedata, communicationsstructures,interface and softwarenecessaryfor studentsto convert the SGML files of their five assignmentsdirectly into HTML documentsfor the Web and into RTF as Word files for print. Evolving the Evaluation Process- Emerging Standards for Student Response The evaluation processalso underwent a major changefrom the previous fall. Instead of the original, single evaluation, the questionswere broken out into four evaluations. Each contained a set of “constant” questions,allowing us to categorizethe responsesinto groups; for example,studentsidentified themselvesas ‘on-’ or ‘off-campus’,working, program year, etc. We launchedthe project knowing we had insufficient online help resourcesand we then supportedindividuals and groups at every stage of the assignmentediting and submissionprocess directly from email responses,phone calls and instructor handling of submissionsfiles. We knew the risks we took and we had been preparedfrom the outsetto pay the price in both instructor overload and studenttitrations that the launch process,as we had designedit, cost. Each evaluation focuseson a different aspectof the course.The first evaluation determinedthe student’seducation level and computer experience.It also sought to determinethe student’sperception of on-campus/off-campus advantagesat the start of the course. The second evaluation dealt with methodsof communication usedin the course: Webchat,email, the newsgroupand the “Instructor’s Comments”.The third evaluation also dealt with communications, but from a different perspective. It askedabout their actual environments for using the course-when, where, what limits and problems, what advantages,when did they chas and with whom, to what effect? We askedstudentshow they felt they had developedin social, as well as technical, ways. Did they start to avoid certain communications?Did Webchat evolve into a social gameas they beganto use it? What subtle, social issuesemerged?The fourth It was during this term that we compiled a series of questionsin the form of an online evaluation. We planned to presentthe studentswith the evaluation once they had submitted final assignment. However, the political processof obtaining approval to presentthe studentswith the online evaluation proved longer than expected. By the time approval was received the coursewas long over. Although we were somewhatupset by this lost opportunity, we realized that we had a working model that could 260 questionsby naive, tiustrated users. We were able to save our bacon, in effect, by handling, on an individual basis, all the technical problems our converter and distribution softwarehad been designedto do automatically. Our instntctorstudentratios remained unacceptablyhigh and the dominant evaluation question “How much doesthis cost?” still had an unacceptableanswer. evaluation was a comprehensiveview, covering aspectsof the course from beginning to end. Brian edited the raw data from eachevaluation into a Web page for general viewing by the students,instructors, and support team. All courseparticipants saw the results, commented on them, among themselvesand in the newsgroups,and made suggestionsto enablethe courseplannersto incorporate good ideasalmost immediately into the coursestructure. The support teamreceived indications of problemsof which they normally were not aware.The course instructors received commentson various assignmentswhile the coursewas still in progress.The studentsreceived instruction by seeinghow the class in general felt about various issuesand they saw their own views reflected in the context of the group and the courseoverall. We resolved this question, in 1997in a Canadian academicenvironment, with studentsproviding their own machinesand Web access.It is $350 $400 per student, per 4-month courseof about 150 hours of student involvement. This doesnot include developmentand marketing costsboth of the coursematerials and the coursewaretools. It doesinclude all instructor time for answering email, handling the news and chat groups, marking all assignmentsand providing support for tutorials. We include somepersonalonline sessionsand help in the forming of the 3-person groups,the administration of the marks and final certification procedures.In addition, we provide technical support for our serversand software, someadvice on communications,editing and conversion strategies. In effect, we believe this to be the amount to cover the operation of a fully developedcourse. It doesnot include hardware and communications, softwaredevelopmentand the upgradesnecessaryto incorporate and describenew Web-basedsoftwareand tools. The number of responsesfor the evaluations varied: 38 for the fust evaluation; 4 1 for the second; 16 for the third; 28 for the fourth. In sum, we felt the number of responseswas encouraging. There was a drop in the number of responsesfor the third evaluation and this may have beenbecausewe askedtoo many questions, too often, at a time when memberswere busy. It may also have beenthat participants were satisfiedwith both the courseprogressand the amount of influence they saw they were having in its evolution. By December 1997we had achievedour objectives: a comprehensive,cost-efficient, interactive coursewhich provided learning for usersin the models of technical writing and the processof SGML documentconstruction. Our participants experiencedself-directed learning, acrossall the resourcesof the Web, the conditions of remote developmentof group projects, using online communicationstools, and the effectivenessof electronic marking and tutorials for their assignments. While the evaluation process,along with the accompanyingfeedback,provided the perception that the instructors and support staff were indeed listening and responding to the students concerns,we conductedno further analysis of the raw data at that time. The next step was to incorporatethe results into a systemwhere we could analyseit and where we could recognize trends. In the fall of 1997, becauseof demandsin other areasand strain on our resources,we had to test our new registration-submission sofhvare,the CourseAdministration Tool, directly on the entire class,while their work was in progress. Instructors had to give simultaneoussupport for the old and new submissionsproceduresrunning concurrently. Even under thesestressful conditions, the integrated coursewareperformed at a level far aboveprevious courseofferings. Studentsexperiencedearly successesat each stageof the preparation and entering of assignmentsand the instructors experienced relief from a myriad of complex, detailed Making Evaluations into Research: Adalysis of the Online Models The on-line evaluation project also evolved. We conducteda review of the materialsto make sure we were asking appropriatequestionsin the correct manner and we were able to apply validity to the processoverall. Doctor Schellenbergdeviseda technique after the fact to format the data in such a way that it could easily be enteredinto SPSSwhere the information could be more closely analyzed. 261 information” section of the evaluation process we discoveredthat there was an even balance betweenthe number of arts/humanitiesstudents and science/technologystudents. The data also revealedthat 38.2% of the studentshad no previous online chat experience. The inclusion of a pseudonymin eachof the evaluations also gave us the ability to track a student from one evaluation to another without compromising his or her identity. For the most part this worked well, with the few exceptions where studentsforgot their original pseudonym. Online communicationsratesamong the most pleasantof our surprises. We were aware of the generalfearsexpressedby naysayersthat electronic learning wou!d stunt human communications,dumb down social interchanges to machine-derivedcommentsand make for a boring or depersonalizedlearning experience. Time constraints obliged us to combine the fust and secondevaluations. This resulted in 57 questionsto the students. The final evaluation contained only 30 questions.We employed considerablecoaxing in the form of repeated, personal emails to get studentsto respondto this last evaluation. We received 56 responsesto the first evaluation and 69 responsesto the second,a slightly lower than participation rate than we expected,considering the class size of 123. By asking so many questions,we may have reduced the number of participation. Studentsmay regard it as simply “too much work to respond” since evaluations have no effect on their course marks and it is obvious that most student issues are addressedand members’concernsare heard and actedupon. Somemay well have felt that they were representedin the broad baseof views put forward by their fellows. We have had no indications of further evaluation needsfrom the classby email requestsor inquiries. Quite the oppositeoccurred. Classmembers worked on assignmentsin relative privacy, using the entire range of coursematerials conveniently, wheneverthey needed.(Pleaseseeurl: httn://udbeam.uwaterloo.ca/-er&lOe/Bookshelf ). They contactedeachother confidently, politely and often via email. They exchanged nestedand attachedmaterials as needed,viewed eachothers’work in an open and congenial way and generally conductedthemselves,acrossfive time zones,like professionals. They found information easily and quickly among FAQs and in the newsgroups,identified specialistsand topic leadersfor generalassistance-- and they also played. Many continue their academicand social contactsacrossterms and somedozen have furthered their studiesin our specialized section of advancedtraining in the subsequent terms. Four now develop materials in the new coursestructure aspart of the instructor group. Top Level Analysis: What We Found The evaluations are composedof five parts: 1. “Background information”, about the students’ profiles, academiclevels and programs Results showedus that initially 35.2% had never usednewsgroups;83.6% had never used StandardGeneralizedMarkup Language, (SGML), which is a requirementto completeall assignmentsin the course. 40.7% of the class had no prior programming experience-a somewhatpredictablenumber considering the balanceof arts and technology students. 2. Questionsabout users’perceptionsof the course,easeof accessto the materials, value of content, and communication choices. 3. Work Group questionsfocusing on how they viewed their contribution and the contribution of others to the 50% of sharedassignmentwork. The evaluation questions“about the course” also offered insight into studentviews of the pedagogyas participants. Gn our seven-point scale,from 1,“very poor”, to 7, “excellent”, 25% of the studentsregardedthe set-up instructions for the courseas “excellent”, while only 6.3 percent felt the instructions were 2 “poor”. 35.4% gave a 6 on the scale;22.9% gave a 5; 4.2% gave a 4; 6.3% gave a 3. No rating of “very poor” was usedby any of the 125 participants. 4. Assignment questionsproviding students’ perceptionsof the relationships and value of assignmentsand marking proceduresto their understandingof writing concepts. 5. General questions such as the overall workload of the course,hours committed the value of work groups and time spent in private versusgroup activities. We were able to make several observationsfrom the basic SPSSdata. From the “background 262 When askedabout the easeof accessto the WWW coursematerial, 76.4% of the classgave a rating of either 1 (very easy) or 2 (easy). Only 3.6% rated the accessas 7 (very hard) or 6 (hard). This is a major commenton the easeand generalavailability of Web accessin just two years from our 1995 fall offering. Then we found that a major component of our work was support for users’connection and familiarization with our basic communications and editing tools. We have moved from an initial student installation requirement of nine piecesof softwareto only three for all coursefunctions in those two years. Moreover, theseprogramshave becomeboth easierto install and more effective to use in eachnew expressionof the products. the studentwho did read the list, 69% did not recognize any of the names,and 25% recognized betweenone and four other students. We anticipatedthe high number of studentswho did not recognize any students,since 69% were distanceeducationstudentsat a remove from the University and eachother. 89% of studentsused email (as one would expect) to contacttheir peersand to font the three-membergroups, followed by face-to-face contacts(3.6%, mostly on campus),and phone (7.3%). From the various contacts,27.3% of the studentsacceptedthe first offer to join a group, while 14%turned down one offer, 36.4% tumed down two offers, and 2 1.8%turned down three or more offers beforejoining a group. The majority of studentfound the experienceof forming groups to be very interesting, as well as being fair. Evaluation on the fly: Short-term,quick responsesin the field The questionsdealing with students’ communication choices showedthe following: 92.6% of the studentsread the newsgroupat least once a week -- 20.4% read the newsgroupmore than 5 times a week. 96.4% of the studentsread the “Instructor’s Comments” at least once a week; of that, 40% read them more than 5 times a week. It is obvious that online communications between student/instructor instructor/studentsand students/studentsplayed a major role in the course. Throughout the design and construction of the online course,we have attemptedkinds of user evaluation at eachstage. Someof thesehave been subjective,casualand inconsistent,usedfor smaller issuesand short-term needs. Others were basedin the experiencesof the course developer-instructors,many of whom were former membersof the class. Someof our assessments were short-term and specific, the needto verify the effectivenessof a part of the technology itself. A University staff member developedour initial course-widesurvey while she was yet a studentin the course. Often, studentswould respond to another students’queries in a news item beforethe instructor had a chanceto reply. The reply was then available for all other studentsto view and it eliminated the need for the instructor to reply individually to studentswith the sameproblem. For the secondand third assignmentsstudents formed groups of three and worked togetherto completethe task for a sharedgrade. The method of group formation was basedon the results of their first assignmentin which they createda resumeand proposal letter. Each studentcould freely view all other students’ resumesand letters, and decide if he or she wanted that person as a memberof their group. The selection processvaried widely as every membersought to find two complimentary people with whom to complete one half of the course. The ways in which they solved the important and complex group formation questionsshow a great deal about how workers interact online. Here are someof those activities and conclusions.When askedif they read the “class nameslist” in the group selection process,40% read all the names,and 20% read most of the names, Only 3.6% did not read the list at all. Of Conclusions and a Sense of Vindication This project hashad somethingof the senseof a grand experimentabout it. Using undergraduate expertiseand academic..credits, we designeda coursewhich parallels many of the experiencesa technical writer undergoesin a first work situation. Even the major metaphorsof an office, bookshelvesand project work groups simulate working conditions for our University’s Co-op studentswho make up a majority of the coursemembership. The involvement of professionalsin several commercialwriting departmentsastutors and advisors addsto this authenticity, as do the large numbersof employeesparticipating to upgradetheir skills and acquire new technical experience. The assignmentsalso follow a pattern of seeking a job through resumes,working in a group to createonline documentationfor software and 263 they are valued and effective from the outset. We hope in this way to begin to collect earlier data than in our previous offerings and simultaneouslyto provide a fuller explanation of what we expect, but of what their predecessors felt and found. creating a multimedia report which analysestheir experiencesof new technology over a protracted period. Course contactsremain for many an addedbonus in new academicand work situations where a former partner can provide information and insights in a new situation by email. Evaluations, in the form of student responses, have also becomea central focus of our developmentof coursematerials. As it is possibleto make electronic expressions interactive, so too is it possible to make learning more immediateto users,by incorporating their views, opinions and activities into the conduct of the course. They take an increasing responsibility and exert a stronger effect on what they learn. Linguists know that languagestudy is descriptive, not prescriptive. By analogy we hope to begin to show our fellow learnersthat the way they seetechnical writing influences what technical writing is as an experience and it is possible for a group to influence itself by its work and by its assessmentsof that work. Our evaluation proceduresform a part of this comprehensiveset of servicesby showing users how the managersof an online learning environment can incorporate individuals’ ideas and the group’s opinions into major changesin coursedesign and operation, sometimeswithin days of the assessmentof a survey. The most important priority for future evaluations is to increasethe participation rate to incorporate all members’opinions. This is necessaryprimarily becausenon-participants can be anticipated to reflect less enthusiasmfor the courseoverall, and that impressionmust be captured if we hope to improve those aspectsof the experiencewhich their silencereflects. This is the next stageof our research,to have user evaluationsand user perfommnce demonstrateto this sameaudienceour students, how they perform as writers in their assignments and how their views influence that activity of writing. All membersundertake, as part of their third assignment,a group exercise in usability through which they devise an objective test for their own documents. It is at this point that the scalesfall off, when they come to seewhat makesa technical writer’s focus -- the audience whose experiencesof their work they witness for the first time on the other side of their egos. As the amount of data from eachof these evaluations increaseswith eachnew offering, we will start to seetrends develop, and we will be able to modify the course in ways to anticipate and reflect them. Getting the entire course design right, particularly in the context of the operating the coursewas an act of courageor folly three years ago. Somethingof the openness we required of our students,as they madetheir assignmentsavailable for all to read, has been capturednow in the candor - and trust - they show in their considerationsof the exercisein thinking they undergo. This is an encouragementall round. We, as instructors, feel we are working with thorough, current information which our learnersprovide because they feel we care and that we use it to provide a more effective experiencefor them. We test all areasof the courseand sharethe results of that assessmentby talking openly about our experiencesand what we can do to improve them for everyone. Brian Cameron’ssynthesisand posting of eachevaluation as it comesin, with our commentsand the actions we take to optimize activities from that information add a’ dimension studentshave not encounteredin other classes. We believe we may now have a way to have studentsseeclearly the results of their class evaluationsand the ways in which their perceptionsinfluence what they expect to learn. From this point they begin their understandingof the online experience. So we plan to add an early explanation of the evaluation objects and processeswith previous examplesof classviews of the course. We will then invite membersto respondto a generaloutline of learning objectives, including what they expect to bring to the coursein motivation, commitment and expectations.This self-evaluation will form the basefor their assessmentsof their subsequent performanceand their emerging senseof their developmentas technical writers. Our plans now include Kathy Schellenberg’s continuing detailed analysis of our results, with a posting of theseinto the commencementof our Septembersections. This will be a way of saying “Welcome” and letting the neophytessee 264