CAB May 2014 - Department of Justice

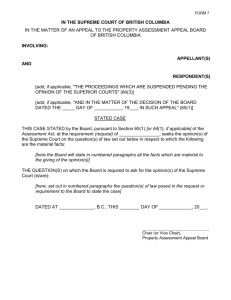

advertisement