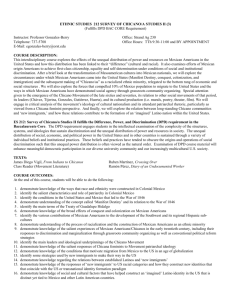

"Heart like a Car": Hispano/Chicano Culture in

advertisement