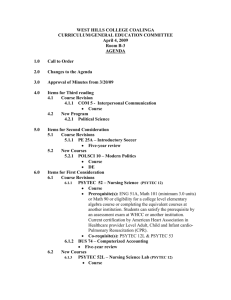

• 001-010.qx - Colorado College

advertisement