Using the 7Ps as a generic marketing mix:

4 MARKETING INTELLIGENCE & PLANNING 13,9

Using the 7Ps as a generic marketing mix: an exploratory survey of UK and European marketing academics

Mohammed Rafiq and Pervaiz K. Ahmed

The 7Ps framework has clear advantages over the 4Ps framework

Introduction

The marketing mix concept is one of the core concepts of marketing theory. However, in recent years, the popular version of this concept McCarthy’s (1964) 4Ps (product, price, promotion and place) has increasingly come under attack with the result that different marketing mixes have been put forward for different marketing contexts.

While numerous modifications to the 4Ps framework have been proposed (see for example Kotler, 1986;

Mindak and Fine, 1981; Nickels and Jolson, 1976;

Waterschoot and Bulte. 1992) the most concerted criticism has come from the services marketing area. In particular Booms and Bitner’s (1981) extension of the 4Ps framework to include process, physical evidence and participants, has gained widespread acceptance in the services marketing literature. The proliferation of numerous ad hoc conceptualizations has undermined the concept of the marketing mix and what is required is a more coherent approach. It is our contention that Booms and Bitner’s (1981) extended marketing mix for services should be extended to other areas of marketing. This article shows how the 7Ps framework can be applied to consumer goods, marketing situations and demonstrates the clear advantages that it has over the 4Ps framework.

Also we present the results of a survey of European marketing academics, that attempts to assess the degree of dissatisfaction with the 4Ps concept and the acceptance of the 7Ps framework as a generic framework.

In order to place the research in context we begin by outlining the theoretical framework underpinning this research. We begin with a discussion of the concept of the marketing mix and the elements that constitute the mix, as there is a considerable variablity in the usage of these terms in the literature.

Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 13 No. 9, 1995, pp. 4-15 © MCB

University Press Limited, 0263-4503

The marketing mix concept

Borden claims to be the first to have used the term

“marketing mix” and that it was was suggested to him by

Culliton’s (1948) description of a business executive as

“mixer of ingredients”. However, Borden did not formally define the marketing mix; to him it simply consisted of important elements or ingredients that make up a marketing programme (Borden, 1965, p. 389). McCarthy

(1964, p. 35) refined this further and defined the marketing mix as a combination of all of the factors at a marketing manger’s command to satisfy the target market. More recently McCarthy and Perreault (1987) have defined the marketing mix as the controllable variables that an organization can co-ordinate to satisfy its target market.This definition (with minor changes) is widely accepted as can be seen from Kotler and

Armstrong’s definition of the marketing mix: as the set of controllable marketing variables that the firm blends to produce the response it wants in the target market

(1989, p. 45).

The essence of the marketing mix concept is, therefore, the idea of a set of controllable variables or a “tool kit”

(Shapiro, 1985) at the disposal of marketing management which can be used to influence customers. The disagreement in the literature is over what these controllable variables or tools are.

The elements of the marketing mix

Borden, in his original marketing mix, had a set of 12 elements namely:

(1) product planning;

(2) pricing;

(3) branding;

(4) channels of distribution;

(5) personal selling;

(6) advertising;

USING THE 7Ps AS A GENERIC MARKETING MIX 5

(7) promotions;

(8) packaging;

(9) display;

(10) servicing;

(11) physical handling; and

(12) fact finding and analysis.

He did not consider this list of elements to be fixed or sacrosanct and suggested that others may have a different list to his. Other suggested frameworks include

Frey’s (1961) suggestion that marketing variables should be divided into two parts: the offering (product, packaging, brand, price, service) and the methods and tools (distribution channels, personal selling, advertising, sales promotion and publicity). Lazer and Kelly (1962) and Lazer et al. (1973), on the other hand, suggest three elements: the goods and services mix, the distribution mix and the communication mix. However, the most popular and most enduring marketing mix framework has been that of McCarthy who regrouped and reduced

Borden’s 12 elements to the now popular 4Ps, namely: product, price, promotion and place (McCarthy, 1964, p.

38). Each of these categories consists of a mix of elements in itself and hence one can speak of the “product mix”,

“the promotion mix”, and so forth. For instance, Kotler and Armstrong list advertising, personal selling, sales promotion and publicity under the heading of promotion.The 4Ps formulation is so popular, in fact, that some authors of introductory textbooks define the marketing mix synonymously with the 4Ps (see for example Pride and Ferrell, 1989, p. 19; and Stanton et al.

1991, p. 13).

While McCarthy’s 4Ps framework is popular, there is by no means a consensus of opinion as to what elements constitute the marketing mix. In fact the 4Ps framework has been subjected to much criticism. Kent (1986), for example, argues that the 4Ps framework is too simplistic and misleading. Various other authors have found the 4Ps framework wanting and have suggested their own changes. For instance, Nickels and Jolson (1976) suggest the addition of packaging as the fifth P in the marketing mix. Mindak and Fine (1981) suggested the inclusion of public relations as the fifth P. Kotler suggests the addition of Power as well as public relations in the context of

“megamarketing” (1986). Payne, and Ballantyne (1991) suggest the addition of people, processes, and customer service for relationship marketing. Judd (1987) suggests the addition of people as a method of differentiation in industrial marketing.

These criticisms and suggestions for change have been largely ad hoc and have arisen out of consideration of specific marketing problems. Much more concerted criticism has come from the areas of industrial and services marketing. These are considered below.

The need for modification of the 4Ps mix

Industrial marketers have long claimed that industrial marketing has features that make it unique and different to consumer marketing. The most important of these features are product complexity and buying process complexity that leads to a high degree of interdependence between buyers and sellers. This has led Webster (1984) to assert that the essence of industrial marketing is the buyer-seller relationship which binds the two together in pursuit of their corporate goals, each becoming dependent on the other. The focus of industrial marketing should not be products but buyer-seller relationships

(Webster, 1984, p. 52).

In the buyer-seller interaction process the influence process is negotiation and not persuasion, as is implied by the marketing mix approach (Webster, 1984, p. 63).

Industrial marketing has, therefore, tended to emphasize the importance of building of relationships in marketing rather than the manipulation of the market through the marketing mix.The criticism levelled at the 4Ps by the interaction/network approach is that personal contacts are rarely discussed and even then only in the context of salesperson-consumer interaction, where the mass marketing approach is insufficient (for example the sale of insurance and cars). Long-term relationships are more important than obtaining immediate sales, as personal relationships can be longer lasting than product or brand loyalties (Gummesson, 1987).

More recently the weaknesses of the goods marketing approach have been exposed by the growing literature on services marketing. There is a growing consensus in the services marketing literature that services marketing is different because of the nature of services. That is, because of their inherent intangibility, perishability, heterogeneity and inseparability (Berry, 1984; Lovelock,

1979; Shostack, 1977) services require a different type of marketing and a different marketing mix (Booms and

Bitner, 1981). The original marketing mix as developed by Borden, it is argued, does not incorporate the characteristics of services, as it was derived from research on manufacturing companies (Cowell 1984;

Shostack, 1977), and it is also argued that there is evidence that 4Ps formulation is inadequate for services marketing (Shostack 1977; 1979).

Various modifications have been suggested to incorporate the unique aspects of services, for example

Renaghan (1981) proposes a three-element marketing mix for the hospitality industry: the product service mix, the presentation mix and the communications mix. A more recent attempt at reformulating the marketing mix is that of Brunner’s 4C’s concept (1989), which comprises the concept mix, costs mix, channels mix and communications mix. The concept mix is broadly equivalent to the idea of the product mix idea, although Brunner claims

6 MARKETING INTELLIGENCE & PLANNING 13,9

that it is better at describing variety of offerings by various types of organizations.The cost concept includes not just monetary costs (i.e., the traditional price element) but also costs incurred by the customer e.g. transportation, parking, information gathering, etc. The channels concept is essentially the same as the traditional place element. The communications element includes not only the traditional, promotional element but also information gathering, i.e., marketing research.

In essence Brunner’s attempt amounts to a change in nomenclature, the 4Ps being replaced by 4Cs. Furthermore, his cost and communications concepts do not strictly adhere to the concept of the marketing mix as a set of controllable variables used to influence the customer: cost incurred by customers in obtaining products such as transport, information gathering and so forth are not under the control of the marketers and, in

Modified and expanded for services

Quality Level

Brand name

Service line

Discounts and allowances

Warranty

Capabilities

Facilitating goods

Payment terms

Customer’s own perceived value

Tangible clues Quality/price

Price interaction

Personnel

Physical

Differentiation environment

Process of service delivery

Location

Accessibility

Distribution channels

Distribution coverage

Source: Booms and Bitner (1981) any case, will vary from customer to customer. Also, marketing research activities per se are not used to influence buyer behaviour, they are used to calibrate the marketing mix variables. Further, Brunner does not show how the 4Cs concept addresses the concerns of services and industrial marketing mentioned above.

The most influential of the alternative frameworks is, however, Booms and Bitner’s 7Ps mix where they suggest that not only do the traditional 4Ps need to be modified for services (see Table I) but they also need to be extended to include participants, physical evidence and process.

Their framework is discussed below.

The Booms and Bitner framework

In Booms and Bitner’s framework participants are all human actors who play a part in service delivery, namely

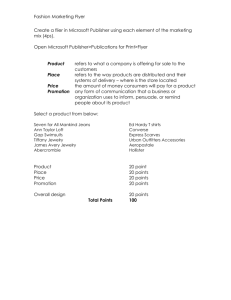

Table I.

The marketing mix

Product

Traditional

Quality

Features and options

Style

Brand name

Packaging

Product line

Warranty

Service level

Other services

Price

Level

Discounts and allowances

Payment terms

Source: Kotler (1976)

Place Promotion

Distribution channels

Distribution coverage

Outlet locations

Sales territories

Inventory levels and locations

Transport carriers

Advertising

Personal selling

Sales promotion

Publicity

Participants Physical evidence Process

Advertising Personnel:

Personal selling Training

Sales promotion Discretion

Publicity Commitment

Personnel

Physical environment

Facilitating

Incentives

Appearence

Interpersonal behaviour goods

Tangible clues

Process of service delivery

Attitudes

Other customers’:

Behaviour

Degree of involvement,

Customer/ customer contact

Environment:

Furnishings

Colour

Layout

Noise level

Facilitating goods

Tangible clues

Policies

Procedures

Mechanization

Employee discretion

Customer involvement

Customer direction

Flow of activities

USING THE 7Ps AS A GENERIC MARKETING MIX 7

the firm’s personnel and other customers. In services

(especially, “high contact” services such as restaurants and airlines) because of the simultaneity of production and consumption, the firm’s personnel occupy a key position in influencing customer perceptions of product quality. In fact, they are part of the product and hence product quality is inseparable from the quality of the service provider (Berry, 1984). It is important, therefore, to pay particular attention to the quality of employees and to monitor their performance. This is especially important in services because employees tend to be variable in their performance, which can lead to variable quality.

The participants’ concept also includes the customer who buys the service and other customers in the service environment. Marketing managers therefore need to manage not only the service provider-customer interface but also the actions of other customers. For example, the number, type and behaviour of people will partly determine the enjoyment of a meal at a restaurant.

Physical evidence in the Booms and Bitner framework refers to the environment in which the service is delivered and any tangible goods that facilitate the performance and communication of the service. Physical evidence is important because customers use tangible clues to assess the quality of service provided. Thus, the more intangible-dominant a service is, the greater the need to make the service tangible (Shostack, 1977). Credit cards are an example of the use of tangible evidence that facilitates the provision of (intangible) credit facilities by banks and credit card companies. The physical environment itself (i.e. the buildings, decor, furnishings, layout, etc.) is instrumental in customers’ assessment of the quality and level of service they can expect, for example in restaurants, hotels, retailing and many other services. In fact, the physical environment is part of the product itself.

The procedures, mechanisms and flow of activities by which the service is acquired are referred to as process in

Booms and Bitner’s 7Ps framework. The process of obtaining a meal at a self-service, fast-food outlet such as

Burger King, is clearly different from that at a full-service restaurant. Furthermore, in a service situation customers are likely to have to queue before they can be served and the service delivery itself is likely to take a certain length of time. Marketers, therefore,have to ensure that customers understand the process of acquiring a service and that the queuing and delivery times are acceptable to customers.

However, supporters of the 4Ps argue that there is no need to amend or extend the 4Ps, as the extensions suggested by Booms and Bitner can be incorporated into the existing framework. The argument is that consumers experience a bundle of satisfactions and dissatisfactions that derive from all dimensions of the product whether tangible or intangible. Buttle (1989) for example, argues that the product and/or promotion elements may incorporate participants (in the Booms and Bitner framework) and that physical evidence and processes may be thought of as being part of the product.

In fact, Booms and Bitner (1981) themselves argue that product decisions should involve the three new elements in their proposed mix (see Table I). Nevertheless, Bitner, while accepting that physical evidence, participants and process could be incorporated into the traditional 4Ps framework, argues that separating them out draws attention to factors that are of “expressed importance” to service-firm managers (Bitner, 1990, p. 70).

Furthermore, Booms and Bitner argue that these new elements are essential to “the definition and promotion of services in the consumers’ eyes, both prior to and during the service experience” (Booms and Bitner, 1981, p. 48).

Furthermore, these elements can be controlled by the firm and used to influence buyer behaviour and hence should be included in the expanded marketing mix:

The potential power of these elements results from the large degree of direct contact between the firm and the customer, the highly visible nature of the service assembly process, and the simultaneity of production and consumption

(Booms and Bitner, 1981, p. 48).

Despite this, introductory texts on marketing, which while propagating the notion that services marketing is different, continue to use the 4Ps framework for services marketing (see for example, Kotler and Armstrong, 1989; and Stanton et al. 1991). However, there is some recognition of the need for change as evidenced by that fact the one of the leading marketing texts in the UK has added people to the traditional 4Ps of the marketing mix variables (Dibb et al., 1994, p. 5).

The need for generic marketing mix

Booms and Bitner in their original article clearly intended the extended marketing mix to be limited to services marketing.This position, of having a separate marketing mix for services, is difficult to maintain, however, when one can find statements in the services literature such as those by Levitt (1981) that:

Everybody sells intangibles in the marketplace no matter what is produced in the factory…

Also that:

…there is no such thing as the service industries. There are only industries whose service components are greater or lesser than those of other industries. Everybody is in service.

(Levitt, 1972, p. 41).

8 MARKETING INTELLIGENCE & PLANNING 13,9

This is similar to Shostack’s view of goods and services as a continuum with goods being tangible-dominant and services being intangible-dominant (Shostack, 1977). In fact, there being few if any pure goods or services as products are usually an amalgam of goods and services.

Similarly, Foxall (1985, p. 2) contends that what is exchanged in a marketing transaction “is a service (or a bundle of services) which may or may not involve the transfer of a physical entity”. Cowell goes even further and contends that there are no fundamental differences between marketing of goods and services:

What differences there are, are of the sort often drawn to distinguish between “consumer marketing” and “industrial marketing” that is differences of degree and of emphasis…the same principles and concepts are of relevance to all fields” (Cowell, 1984, p. 36).

If that is the case then why should the marketing mix be different for goods and services? As Enis and Roering

(1981) point out, if the product is defined as a bundle of benefits (with tangible and intangible elements) then the call for a unique services marketing strategy is inconsistent with such a definition of the product.

In light of the above, what is needed is a marketing mix which cuts across the boundaries of goods, services and industrial marketing, i.e. a generic marketing mix. It is contended here that the Booms and Bitner framework can and should be extended to goods and industrial marketing and that there are distinct advantages in doing this. Below it is shown how the 7Ps framework can be extended to goods marketing.

7Ps and consumer goods marketing

In the goods marketing framework the product, promotion and pricing of the product is controlled by the manufacturer, but distribution is normally delegated to marketing intermediaries. One has to ask what services the distributor provides to the manufacturer and the consumer. It is quite evident from the reference to the distribution function as “place” in the 4Ps framework that the distributors’ role in providing somewhere for the consumer to obtain goods is well accepted and understood. Intermediaries also provide people to explain product features and to market the products, and the demeanour and training of these staff can be crucial in the selling of goods. Furthermore, presence or absence of other customers can be a factor in buyer-behaviour. For example, long queues at check-outs in supermarkets put many customers off from shopping there. Intermediaries also control the process to some extent of obtaining goods. This relates not only to queuing at the check out but may also include, packing, delivery, maintaining waiting lists and ordering goods from manufacturers on the customers’ behalf and may include membership schemes as in the case of warehouse clubs. Intermediaries, such as retailers, are also responsible for the physical evidence of the environment in which consumer products are sold. Department stores and warehouse clubs, for instance, are distinguishable from each other from their retail environments alone.

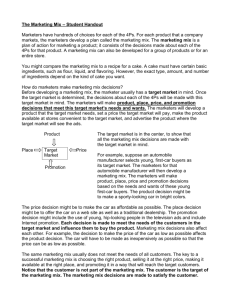

Figure 1 illustrates the fact that in goods marketing, the participants, physical evidence and process parts of the extended marketing mix are normally delegated to distributors. This is because normally these elements make very little difference to the quality of the delivered product in consumer goods marketing and what is important is wide distribution. Where quality, or the image of the product is affected, intermediaries may be eliminated. This is particularly likely to occur if the manufacturer produces a deep range of products.

Examples of this process include, Thorntons (a UK manufacturer and retailer of quality chocolates),

Benetton, and Disney stores.The case of Thorntons is instructive: the chocolate manufacturer has its own retail outlets to emphasize the exclusivity of Thorntons’ chocolates and to ensure that chocolates are of the high quality that customers expect from Thorntons. The elimination of intermediaries, or at least the shortening of the distribution channel, is also likely to occur where the product requires a high degree of service (cars, for example).

In contrast, in services marketing, all parts of the mix are normally under the direct control of the service providers

(see Figure 1); i.e. services are less frequently distributed through intermediaries. Some services are, however, distributed through intermediaries (for example package holidays, and insurance, etc.). This is most likely to occur where a standardized, prepackaged service can be

Figure 1.

The extended marketing mix and the relationship between producers and intermediaries in goods and services marketing

Physical goods

Producer

Product

Price

Promotion

Place

Participants

Process

Physical evidence

Key

Normal route

Less frequent route

Intermediaries

Place

Participants

Process

Physical evidence

Customer

Services

Producer

Product

Price

Promotion

Place

Participants

Process

Physical evidence

USING THE 7Ps AS A GENERIC MARKETING MIX 9

offered. McDonald’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Dominos

Pizza provide good examples of where a standardized product is distributed via an intermediary (namely a franchisee). In all these examples the producers maintain strict control over the product, promotion, the prices charged, the physical location, look and layout of the outlet, and operating procedures and standards. This is only possible because the producers are able to lay down exact specifications for their products. Hence, where service delivery can be standardized and the quality of service easily controlled and monitored, services marketing resembles goods marketing. In fact, service marketers should be actively seeking to standardize their services or “industrialize” services as Levitt (1976) puts it.

Even in these examples, however, the channels of distribution tend to be short. Similar analysis can be extended to other types of marketing.

As far as we are aware, there is no empirical research available to date that tests the satisfaction of marketing academics with either the 4Ps or 7Ps framework. It was, therefore, decided to conduct a survey to find out which of these frameworks marketing academics were using, and how and why they were using them.

excluded. The first mailshot was sent out in July 1992. A follow-up letter and questionnaire were sent in mid-

September 1992. A total of 59 replies were received, a response rate of around 26 per cent which is a fairly typical response rate for postal questionnaires. The majority of the respondents were from European and US institutions, with a few from other parts of the world. The profile of the respondents, in terms of the place of origin, was fairly representative of the (non-UK) delegates present at the 1992 EMAC Conference.

Of the EMAC respondents: 17 were professors, 17 associate professors (30 per cent of the sample), 18 (32 per cent) assistant professors, and four were research students. The average number of years of teaching experience was 13.4 with a minimum of one and a maximum of 34 years (95 confidence interval of 10.57-

15.72). We believe this to be a representative profile of

EMAC delegates and that it reflects the international standing of the EMAC. The UK sample, on the whole, was less experienced with an average of 8.73 years of experience in teaching marketing (95 confidence interval of 7.7-9.77). The sample included only five full professors

(11.6 per cent of the sample), 17 associate professors (i.e.

senior lecturers) equivalent (39.5 per cent), 17 assistant professors (i.e. lecturers) and four research fellows/ students (9.3 per cent of the sample). This is also believed to be a representative picture of MEG delegates and that it reflects the national standing of the conference.

Methodology

The target respondents of this survey were the delegates of the UK’s Marketing Education Group (MEG)

Conference held in Salford in 1992 and the European

Marketing Academy (EMAC) Conference held in

Aarhaus, Denmark in May 1992. The two conferences were selected because they are probably the two largest annual marketing conferences in Europe. Also the two conferences provided the opportunity to compare the views of the participants of one conference with a national reputation (MEG) with those of the participants of a conference with an international reputation (EMAC).

It was believed that the participants of the two conferences had different profiles and that this may be a factor in the opinions held by the respondents.

To maximize the response rate a modified-mail-survey approach was used. For the UK respondents: the questionnaires were handed out at the MEG Conference in July 1992 and in mid-September a follow up letter and questionnaire were sent. A total of 46 usable questionnaires were received giving a response rate of 24 per cent for UK marketing academics.

A postal questionnaire was also sent out to all non-UK academic participants of the EMAC Conference in

Aarhus in Denmark in 1992. To prevent overlap between respondents, the delegate-lists were carefully compared before sending out the mailed questionnaires and UK participants of the EMAC Conference were systematically

Results

Dissatisfaction with the 4Ps

A large majority of the respondents (78 per cent of EMAC delegates and 84 per cent of the MEG delegates) felt that the 4Ps concept was deficient in some respects as a pedagogic tool. (The difference in the proportions of MEG and EMAC delegates’ dissatisfaction is not statistically significant.) In fact, 75 per cent of the EMAC respondents had used modified versions of the 4Ps concept at some time or other. Of these, 82 per cent (or 62 per cent of the total sample) said that this was a regular occurrence.

Similarly, 84 per cent of MEG respondents had used a modified version of the 4Ps and of these 84 per cent had found this to be a regular occurrence. Examination of the data showed that the level of dissatisfaction expressed did not appear to be influenced by length of experience in teaching marketing or the status (i.e. the seniority) of the respondents; i.e. full professors were just as likely to be dissatisfied with the 4Ps as junior marketing academics.

The respondents were further probed as to how adequate they felt the 4Ps were for various types of marketing situations, as it was felt that the dissatisfaction probably varied across subjects. This was largely borne out (see

Tables II and III).

10 MARKETING INTELLIGENCE & PLANNING 13,9

Table II.

A comparison of the dissatisfaction of UK and European academics with the 4Ps framework for various types of marketing course

Type of marketing

Totally adequate

%

Introductory

Consumer

Retail

International

Strategic

Industrial

Not-for-profit

Services

Average

UK

European

UK

European

UK

European

UK

European

UK

European

UK

European

UK

European

UK

European

UK

European

34

27

5

18

0

11

2

7

2

5

2

8

0

9

2

6

7

11

Note: Row percentages may not add up to 100 owing to rounding

27

13

13

9

11

9

19

21

18

20

48

44

52

29

27

28

26

23

Degree of satisfaction/dissatisfaction

Adequate

%

Just about adequate

%

Problematic

%

23

27

18

28

16

25

26

27

24

27

7

15

21

31

27

33

20

27

43

46

51

44

64

51

45

37

47

35

21

18

42

22

7

9

41

33

Unusable

%

16

13

5

7

7

9

11

9

7

8

2

4

2

4

5

6

7

6

Number of respondents

44

55

45

54

45

55

42

52

45

55

46

54

44

55

41

54

100%

100%

Table III.

Overall dissatisfaction with the 4Ps framework for various types of marketing courses among the entire sample

Type of marketing

Totally adequate

%

Adequate

%

Introductory

Consumer

Retail

International

Strategic

Industrial

Not-for-profit

Services

Percentage of all responses

31

12

6

5

5

5

4

4

47

39

27

20

19

19

11

10

9 24

Note: Row percentages may not add up to 100 owing to rounding

Degree of satisfaction/dissatisfaction

Just about adequate

%

Problematic

%

26

25

23

21

11

26

31

27

40

44

48

57

8

19

31

40

24 36

Unusable

%

10

6

14

8

5

7

3

3

7

Number of responses

100

99

99

100

100

99

95

94

100

The 4Ps were thought to be most inadequate for services, not for profit and industrial marketing. Of the respondents

51 per cent felt that the 4Ps were either problematic or unusable for services. Similarily, the figures for not-forprofit and industrial marketing were 63 per cent and 62 per cent respectively.These are the areas that have generated most criticism of the 4Ps marketing mix. Conversely, the areas where the 4Ps are thought to be most useful are