Person-Culture Fit and Employee Commitment in Banks

advertisement

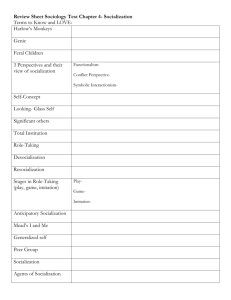

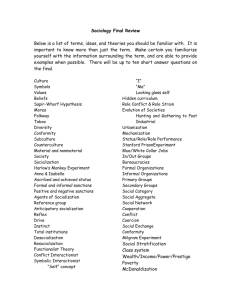

R E S E A R C H includes research articles that focus on the analysis and resolution of managerial and academic issues based on analytical and empirical or case research Executive Summary KEY WORDS Value Congruency KEY WORDS Socialization Practices Privatization Normative Commitment Indian Banking Organizational Culture Efficiency Profile Performance Person-Culture Fit and Employee Commitment in Banks Nazir A Nazir This paper makes an attempt to ascertain the relationship between socialization, person-culture fit, and employee commitment. In other words, it seeks to determine whether the organizations high on socialization scores will experience high value congruency/person-culture fit and also whether high value congruency leads to employee commitment. In the recent past, the concept of culture has gained wide acclaim as a subject of study and reflection. However, the parameters of culture are so intricate that they cannot be outlined or defined. While contemporary research fully endorses the view that culture is an internal variable and can be conceptualized in terms of widely shared and strongly held views, the researchers have not empirically investigated the relevance of social learning in permeating these values into the organizational members. This paper seeks to overcome this limitation and also deviates from the earlier research studies undertaken in this field in the Indian context by exploring whether the person-culture fit notion or the integration of organizational values and individual preferences for those values could predict employee commitment. This study was conducted on six banks including two public sector (banks 1 and 2), two private sector (banks 3 and 4), and two foreign banks (banks 5 and 6) located in Delhi. It used three wellestablished scales — organizational culture profile (OCP), organizational commitment scale (OCS), and socialization practices scale (SPS) — to collect data from two separate groups of respondents through convenience sampling procedure. The first group consisted of 135 newly recruited employees who were asked to complete the OCP indicating their individual preferences on the given 54 value items and OCS for ascertaining their commitment. The second group comprised of 69 senior employees of the banks studied. An overall profile of the culture of each bank was developed by averaging the individual responses of this group. These were then used to calculate the person-culture fit scores for the newly hired employees. The main findings of the study are as follows: Moderate to strong person-culture fit score was found in one private and two foreign banks and weak to moderate person-culture fit score was found in rest of the banks studied. Two foreign and one private bank scored high to moderate on socialization practices respectively. The other two public and one private bank scored low on this dimension. Banks high on value congruency and socialization scores showed significant correlation between person-culture fit and normative commitment. Banks low on value congruency and socialization practices exhibited insignificant correlation between person-culture fit and normative and instrumental commitment. On the whole, the study indicates the need for firms, especially public sector, service-oriented firms, to pay attention to socialization practices which would result in strong cultures and employee commitment. VIKALPA • VOLUME 30 • NO 3 • JULY - SEPTEMBER 2005 39 O rganizational culture has emerged as one of the crucial and important concepts in the field of organizational behaviour and human resource management in the recent past. The efforts aimed at ascertaining the factors responsible for various organizational outcome variables — employee commitment, job satisfaction, turnover, absenteeism, etc. — have been almost overshadowed by the recent penchant of scholars towards understanding the cultures of organizations and their strength in shaping the behaviour of organizational members (Calori and Sarnin, 1974; Denison and Mishra, 1995; Gordon and DiTomaso, 1992; Kanungo and Mendonca, 1994; Koene, 1996; O’ Reilly, Chatman and Caldwell, 1991; Pathak, Rickards and Pestonjee, 1996; Sheridan, 1992; Wilderom and Van den Berg, 1998). Further, with some differences over the definition and measurement of organizational culture, researchers suggest that culture may be an important factor in determining how well an individual fits into an organizational context (Caldwell and O’ Reilly, 1990; Kilman, Saxton and Serpa, 1986). The approach suggests that both the characteristics of the individual and that of the organization predict his/her behaviour at work (Schneider, 1987; Terborg, 1981). Drawing on interactional psychology, some researchers (Holland, 1985; Joyce and Slocum, 1984) point out that certain aspects of individuals such as values, expectations, beliefs, etc., interact with organizational facets such as reward systems, norms, and traditions to influence the individuals’ attitudinal and behavioural responses. Having a set of values that is both commonly shared and strongly held by the organizational members may be especially beneficial to firms operating in the service sector. As George and Marshall (1984) pointed out, the members of these organizations are responsible for delivering service. Further, it is in the service sector organizations that members remain in close touch with their clients and hence their behaviour, attitude, and relationship may, by and large, truly represent the firm’s espoused values. It becomes imperative for the management of such organizations, therefore, to imbue in letter and spirit, the ethos and values of the firm in them so that their behaviour, attitudes, and actions at workplace are in consonance with the firm’s culture (Nazir, 2000). In this context, the system of control mechanism prevalent in the organization plays a pivotal role in directing the actions of individual members. Researchers argue that the formal control mechanisms are more 40 relevant in the manufacturing sector because of processes and products being more tractable (Bravermann, 1974). On the contrary, since the service sector has a very high frequency of off-site work, multiple engagements, and a good number of professional staff, social control mechanisms, such as cultural values, are found preferable to imbue member’s actions (Magnet, 1993; Norman, 1984). These control mechanisms have far-reaching implications for organizational members. One such implication is the congruency between individual and organizational values. It has been argued that, drawing on underlying values, individuals may manage their lives in ways that help them choose congruent roles, occupations, and even organizations (Albert and Whetten, 1985; Stryker and Serpe, 1982). Schneider (1987) proposed that individuals may be attracted to organizations they perceive as having values similar to their own. Similarly, organizations attempt to select recruits who are likely to share their values. New entrants are then further socialized and assimilated and those who do not fit leave. Thus, basic individual values or preferences for certain modes of conduct are expressed in organizational choices and then reinforced within organizational contexts. Moreover, according to Chatman (1989), values provide the starting point and the process of selection and socialization jointly acts as a complementary means to ensure person-organization/culture fit. Thus, congruency between individuals and organizational values aimed through socialization may be at the crux of person-culture fit. Previous research has not studied the influence of socialization in augmenting person-culture fit in organizations. For example, Chatman and Jehn (1994) studied only the relationship of two individual characteristics — technology and growth — with organizational culture. O’Reilly, Chatman and Caldwell (1991), while measuring person-organization fit in government agencies and private accounting firms, neglected the role of socialization in fostering value congruency in the sample organizations. Further, strong congruence between individual value preferences and organizational values is believed to result in strong employee commitment. For example, Virtanen (2000) asserted that the strength of culture can be easily conceptualized as the strength of commitment. Brown (1995) indicated that a strong culture is usually understood to be synonymous with consistency: beliefs and values are “shared relatively consistently throughPERSON - CULTURE FIT out an organization.” Thus, management of culture is treated as management of commitment. It has been argued that the fit between individual preferences and organizational cultures would lead to increase in commitment because both job satisfaction and organizational commitment can be predicted with this fit (O’Reilly, Chatman and Caldwell, 1991). However, research on assessing the cultural gap, i.e., the difference between actual organizational norms and desired individual norms and their impact on organizational outcome variables such as performance, satisfaction, and employee commitment, is still limited (Wilderom, Glunk and Maslowski, 2000). This study, therefore, makes an attempt to assess and compare the cultural gap, employee commitment, and socialization programmes in six banks in India. In this study, organizational culture has been conceptualized and quantified in terms of widely shared and strongly held values. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY The primary objective of this study was to discover the compatibility between organizational culture values and individual preferences and the role socialization played in augmenting value congruency. The study also attempted to ascertain the relationship between value congruency and employee commitment (Figure 1). Hypothesis 1: The level of commitment will vary with the level of value congruency — high level of person-culture fit (value congruency) would be positively associated (and low level of person-culture fit would be negatively associated) with employee commitment based on organizational values. Some studies have suggested that organizations which emphasize on socialization process, viz., rigorous recruitment and selection procedures, and focus on organizational values and reward system are more likely to be high on value congruency resulting in cultural continuity (Major, 2000). In the course of socialization, new entrants are introduced to organizational norms that apprise them about how to behave in various situations. Besides, it is believed to help them accurately grasp the organizations’ internal culture including values, attitudes, and perspectives. Researchers such as Caldwell and O’Reilley (1990) argued that socialization facilitates introduction to the new recruits both with the specific job and with the organization’s culture. Against this backdrop, the following hypothesis was formulated to test whether socialization influences value congruency. Hypothesis 2: Organizations with high emphasis on socialization will experience strong value congruency. METHODOLOGY Sample Six banks including two public sector (banks 1 and 2), two private sector (banks 3 and 4), and two foreign banks (banks 5 and 6), participated in the study. Data were collected from two separate groups of respondents through convenience sampling procedure. Group 1 consisted of 135 newly recruited employees representing the above six banks. They were asked to complete the organizational culture profile (OCP), to indicate their individual preferences on 54 organizational value items Figure 1: The Model Organizational culture values Value orientation/ Socialization process Value congruency Employee commitment Employees’ individual preferences VIKALPA • VOLUME 30 • NO 3 • JULY - SEPTEMBER 2005 41 and organizational commitment scale (OCS) for ascertaining their level of commitment. In Group 1, men comprised of 71 per cent of the employees and the average experience of all the employees was 2.9 years. This group was used to ascertain the individual preference profile. Group 2 comprised of 69 senior employees of these six banks. Eighty three per cent of these respondents were men and they had more than five years’ experience in their banks. An overall profile of the culture of each bank was developed by averaging the individual responses. These were then used to calculate the personculture fit scores for the newly hired employees (Group 1). Measures Used Three psychometrically valid and tested scales were used for this study: Organizational culture profile (OCP), organizational commitment scale (OCS), and socialization practices scale (SPS). However, the main scale was modified to measure person-culture fit to suit the sociocultural context of this investigation. A brief description of the scales used is given below: Organizational Culture Profile (OCP) Developed by O’Reilly, Chatman and Caldwell (1991), this instrument contains value statements which are characteristically relevant to the target organization and to the individual preferences. The correlation between the organizational value profiles and the individual value profiles determines the person-culture fit. In order to make the scale more relevant and reliable in our sociocultural setting, some suitable changes were made as indicated earlier. This was done by placing the value statements of the original scale before some management experts and scholars. Keeping in view the peculiar demand of the scale, the total number of items in the original scale stood unchanged. However, 15 items were found replaceable after the above procedure was followed (see Box for a description of OCP). Pilot Study: A pilot study of the scale was undertaken on 35 employees and the split-half test was employed to measure the reliability of the modified scale. This test produced a correlation coefficient of 0.53. The reliability of the overall scale was 0.69. Organizational Commitment Scale (OCS) The scale developed by O’Reilly and Chatman (1986) was used to measure organizational commitment. Twenty-one variables representing compliance, identi- 42 Box: Description of OCP OCP is based on the Q-Sort profile comparison process in which the respondents are presented with a large number of items. They are then asked to sort them into a specific number of categories ranging, for instance, from the most to the least desirable or from the most to the least characteristic and to put a specified number of statements in each category; the required item category pattern is 2-4-6-9-12-9-6-4-2. OCP contains 54 value statements assessing attitudes towards, for instance, quality, respect for individuals, flexibility, risk-taking, etc., which emerged from a review of academic and practitioner-oriented writings on organizational values and culture.Thirty-eight business administration majors and four business school faculty members screened an initial 110-item deck for items that were redundant, irrelevant or difficult to understand. A similar check was made with an independent set of respondents from accounting firms. After several iterations, a final set of 54 values was retained (O’Reilly, Chatman and Caldwell, 1991). Test-retest reliability of the scale over a 12-month period was quite high (median r=0.74, range = 0.65 0.65-0.87). fication, and internalization dimensions were included (Buchanan, 1974; Mowday, Steers and Porter, 1979). For example, seven compliance items were developed based on Kelman’s (1958) original formulation of compliance as behaviour engaged in to obtain specific rewards (e.g., “Unless I am rewarded for it in some way, I see no reason to expend extra effort on behalf of this organization” and “In my job here, I somewhat have to act in ways that are not completely consistent with my true values”). For reflecting identification with the organization, again, seven items were included in the scale (e.g., “This organization has a tradition of worthwhile accomplishments”). In order to assess internalization, a final set of seven items in the concerned scale (e.g., “Since joining this organization, my personal values and that of the organization have become more similar”) was included. Respondents were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed or disagreed with each one of the statements on a 7-point scale. A principal component analysis with a varimax rotation on the 21 items of the scale showed four interpretable factors defined by 12 of the 21 items. This reduced set was again analysed and three clear factors emerged, viz., internalization, identification, and compliance. To ensure orthogonality among the three commitment dimensions, the factor scores were further computed and used in subsequent analysis. Correlations among the factors ranged from r=-0.01 to -0.06. Socialization Practices Scale (SPS) The questionnaire developed by Pascale (1985) was used to measure the socialization practices of the banks studied. This scale consists of 16-items designed to measure the degree to which companies engage in actions or have policies similar to those of companies that have a repuPERSON - CULTURE FIT tation for successfully recruiting and socializing newcomers. For comparison, the scale categorizes the organizations into strong, medium, and low levels of socialization based on the total scores obtained from each organization. RESULTS OF THE STUDY The research design of the study required information from two types of respondents using OCP. The Group 2 respondents labelled as raters were asked to describe categories on the basis of how important each item was to characterize their organization. The Group 1 respondents were asked to describe how important it was for the person that the characteristic represented be a part of an organization’s culture by sorting the 54 value items into nine categories. In essence, the former group was to describe the culture of their organization on 54 value items and the latter was to record their individual preferences on the same 54 value items. Therefore, it was imperative to ascertain whether the OCP discriminated among the individuals and the organizations in terms of their central value system. Here, it is important to mention that the dimensions of individual preferences and organizational culture should be comparable because it is this comparability which can ensure the validity of the person-culture fit notion used in this study; otherwise, its relevance would be questionable. To address these vital issues, two separate factor analyses using principal component analysis with varimax rotation were conducted, one for individual preferences and another for organizational culture. The results of the analysis reported in Tables 1 and 2 indicate that person-culture fit possesses predictive validity and is organizationally useful. Dimensionality of Individual Preferences and Organizational Culture Values The OCP responses in each firm from both types of subjects were factor analysed using principal component analysis with varimax rotation method. Out of the entire set of 54 value items from Group 1 (n=135), 29 items had loadings greater than 0.40 on a single factor (Table 1). From a scree test, seven interpretable factors with eigen values greater than 1.0 and defined by at least three items emerged: innovation, team orientation, orientation toward rewards, emphasis on aggressiveness, attention to detail, respect for people, and orientation VIKALPA • VOLUME 30 • NO 3 • JULY - SEPTEMBER 2005 towards outcome. Six of the factors exactly resemble the factor results of O’Reilly, Chatman and Caldwell’s (1991) study. The uncommon factor in our study is ‘respect for people’ while it is ‘supportiveness’ in the aforementioned study. These two factors can, however, be viewed as synonyms. The factor pattern as presented in Table 1 is strongly supported by the extant literature on culture (Chatman and Jehn, 1994; Deal and Kennedy, 1982; Hofstede, 1998; Peters and Waterman, 1982; Schneider, Gunnarson and Niles-Jolly, 1994). The factor analysis using principal component analysis with varimax rotation method was also performed on Group 2 (n=69). This was done with two objectives in mind. One, to see whether OCP reflects the meaningful organizational dimensions and two, to find out whether the individual and organizational matrices were similar. Here, 32 items with loadings above 0.40 were retained. Table 2 shows the factor loadings for 32 items that loaded cleanly on factors retained after a scree test. Eight interpretable factors with eigen values greater than 1.0 emerged: innovation, orientation towards customers, stability, emphasis on procedures, team orientation, orientation towards rewards, outcome orientation, and easy-goingness. A comparison between the dimensions as envisaged in Tables 1 and 2 reveals that while four factors, namely, innovation, rewards orientation, team orientation, and outcome orientation are replicated almost exactly, the other two factors — attention to detail and respect for people (Table 1) and emphasis on procedures and customer orientation (Table 2) — also have close resemblance with each other. Although research indicates that direct comparison of the factor structures could be misleading because of the different stem questions, the above results appear to depict a good comparability between cultures as defined by individual preferences and actual organizational descriptions. These results suggest that OCP can provide a reasonable mapping of organizational culture. Assessment of Inter-rater Agreement on Firm Values Before reporting the tests of hypotheses, the results of OCP are presented. As discussed earlier, the important assumption in the use of OCP is that a firm’s value system can be represented in a single profile. This, therefore, called for averaging the firm informant’s Q Sorts to ascertain whether there was high consensus among members about organizational values. As such, the firm informant’s Q Sorts were averaged, item by item, for each OCP dimension representing each firm. 43 Table 1: Results of Factor Analysis of Individual Preferences Organizational Culture Profile Items High expectation for performance High pay for good performance Praises for performance Ability utilization Team orientation People orientation Supportiveness Collaboration Flexibility Adaptability Taking advantage of opportunities Taking initiative Being competitive Highly organized Aggressiveness Action orientation Individual responsibility Being analytical Attention to detail Emphasis on paper work Knowledge of procedures Achievement orientation Emphasis on quality Result orientation Social responsibility Promptness in services Interest in customers Courteous treatment Helpful attitude Eigen values Proportion of variance accounted for Rewards Orientation Factor 1 Team Orientation Factor 2 Innovation Factor 3 Aggressive ness Factor 4 Attention to Detail Factor 5 0.59 0.49 -0.64 0.87 0.12 0.03 0.31 0.16 -0.13 0.16 0.09 0.09 -0.02 0.11 0.17 0.13 0.11 0.13 0.07 0.11 0.05 0.12 0.05 -0.11 -0.16 0.17 -0.15 0.13 0.11 2.19 7.56 -0.30 0.25 0.05 -0.02 0.44 0.43 -0.49 0.52 0.10 -0.09 -0.25 -0.14 0.17 -0.24 0.21 0.08 -0.09 0.08 0.23 0.17 0.12 -0.16 0.18 0.19 0.05 -0.14 -0.13 0.12 -0.24 2.15 7.39 0.19 0.18 -0.03 -0.08 0.06 -0.21 0.13 0.07 0.56 0.11 -0.43 0.41 0.46 0.45 -0.03 0.23 -0.12 0.06 0.07 0.21 0.15 0.15 0.14 0.14 0.24 0.27 0.2 0.19 0.29 2.09 7.21 0.24 0.23 -0.18 0.19 0.27 0.11 0.16 0.15 -0.01 -0.13 -0.32 0.07 0.31 -0.14 0.63 -0.48 0.59 0.18 0.09 0.24 0.21 0.21 -0.07 0.17 -0.31 0.27 0.18 0.09 0.19 2.07 7.13 0.05 0.01 0.00 0.04 0.09 0.07 0.03 0.06 0.11 0.06 -0.06 0.00 -0.05 0.02 0.04 0.13 0.09 0.05 0.44 0.41 0.51 -0.09 0.03 0.04 0.01 0.04 0.12 0.08 -0.13 1.99 6.86 Outcome Respect Orientation for People Factor Factor 6 7 -0.06 -0.04 0.13 -0.06 0.23 0.18 -0.08 0.12 0.19 0.24 0.14 0.11 -0.15 0.10 0.05 0.06 -0.13 0.17 0.16 0.06 0.05 0.65 -0.47 -0.59 -0.18 -0.18 -0.07 0.11 0.27 1.52 5.24 0.04 -0.11 -0.06 0.08 0.03 0.09 0.01 0.08 -0.30 0.06 0.04 0.02 0.09 -0.15 -0.04 0.01 -0.09 0.04 0.07 0.11 0.05 0.06 0.11 0.04 0.51 0.42 0.49 0.51 -0.48 1.51 5.21 Note: Figures in bold represent loadings greater than 0.40 on that factor. Using James’ (1982) formula, intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated for ascertaining the member consensus on each dimension. ICC was calculated by using the following formula: Between MS - Within MS ICC = ———————————————————— Between MS + (k - 1) (Within MS) where MS is the mean squares and k is the number of respondents in the sample organization. On account of varied number of respondents in each bank ranging from 9 to 16, a harmonic mean of 38.46 was used as k for calculating ICC (for further details, see Bartko, 1976; James, 1982). The ICCs in Table 3 range from 0.199 to 0.325. All the ICCs are significant indicating that there is a strong consensus among firm informants on the prevalence of given organizational culture value. 44 Assessment of Person-culture Fit (Value Congruency) The person-culture fit score for each individual was ascertained by correlating the individual preference profile with the profile of the bank for which the employee worked. Using Boyd, Westfall and Stasch’s (1996) criteria for ascertaining the strengths and weaknesses of the correlations between the two variables, the correlation coefficients in Table 4 show a moderate to strong person-culture fit score for banks 4, 5, and 6 and weak to moderate score for the rest of the banks studied. The overall person-culture fit score was computed by calculating the individual preferences based on the responses of the newly recruited employees for each individual firm separately. Secondly, the average firm profile was calculated on the basis of the responses of PERSON - CULTURE FIT Table 2: Results of Factor Analysis of Firm Descriptions (n = 69) Organizational Culture Profile Items High expectation for performance Rewards Outcome Innovation Procedural Team Customer Orientation Orientation Orientation Orientation Factor Factor Factor Factor Factor Factor 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stability Factor 7 Easygoingness Factor 8 0.18 0.56 -0.13 -0.10 -0.06 0.03 0.23 0.12 -0.61 0.21 0.18 0.09 0.31 0.28 0.09 0.14 High pay for good performance 0.81 0.19 0.06 0.08 -0.09 0.11 -0.13 0.28 Praises for performance 0.59 0.11 0.31 -0.27 0.08 0.09 0.11 -0.13 Achievement 0.37 0.81 0.02 -0.11 0.23 0.14 -0.08 0.19 0.21 -0.49 0.14 -0.07 0.11 -0.17 0.03 0.06 -0.15 Professional growth orientation Emphasis on quality Results orientation 0.03 0.64 0.27 0.12 0.09 0.14 0.07 Flexibility 0.33 0.04 -0.57 0.12 -0.15 0.11 -0.17 0.06 Adaptability 0.06 0.19 0.41 0.08 0.17 0.11 -0.16 0.09 Innovation 0.07 0.10 0.68 0.15 0.03 0.31 0.29 -0.24 -0.12 0.24 -0.71 0.29 0.13 0.09 0.13 0.17 Experimenting with new ideas 0.23 0.08 -0.48 0.14 0.11 0.07 0.12 0.09 Being careful 0.29 -0.13 0.15 -0.48 0.12 0.12 0.09 0.17 Attention to detail 0.15 0.12 0.17 0.57 0.15 0.19 0.22 0.08 Paper work 0.12 0.18 -0.12 0.61 0.22 0.06 0.23 0.02 Spirit rather than letter ethos 0.06 0.11 0.08 -0.52 -0.21 0.07 0.29 0.05 Knowledge of procedures 0.11 -0.01 0.10 0.76 0.31 0.09 0.23 0.34 Simplification of procedures 0.14 -0.31 0.18 0.52 -0.05 0.08 0.03 0.01 Taking advantage of opportunities People orientation 0.15 0.26 -0.21 0.09 -0.56 0.21 0.03 0.13 Supportiveness 0.18 -0.08 0.21 0.06 0.42 0.32 0.19 0.18 Developing friends 0.03 0.36 0.24 0.12 -0.56 0.28 0.03 0.14 Collaboration 0.11 0.19 -0.08 -0.14 0.63 0.09 0.14 0.18 Interest in customers 0.04 -0.11 0.24 0.13 0.08 0.53 0.12 0.21 0.18 Courteous treatment 0.09 0.12 -0.15 0.17 0.06 0.59 0.23 Respect for timing 0.23 -0.10 0.14 0.01 0.18 0.49 0.12 0.08 Efficient dealing 0.08 -0.15 0.05 -0.18 0.22 0.57 0.09 0.05 Predictability 0.19 0.10 0.21 -0.14 0.30 -0.07 0.48 0.03 Individual responsibility 0.21 0.01 0.26 0.09 0.22 -0.12 0.62 0.02 Security 0.08 0.04 -0.12 0.06 0.23 0.06 0.51 0.11 Easy-goingness 0.09 0.12 0.14 0.12 -0.06 -0.04 0.18 0.59 Calmness 0.01 0.16 0.29 -0.02 0.14 0.06 0.08 -0.73 Decisiveness -0.12 0.11 0.05 0.31 0.17 0.21 -0.07 0.43 Eigen values 2.46 2.06 2.53 2.49 2.02 1.93 1.53 1.09 Proportion of variance accounted for 7.68 6.44 7.89 7.81 6.33 6.02 4.78 3.40 Note: Figures in bold represent loadings greater than 0.40 on that factor. Table 3: Results of ANOVA and ICC Organizational Culture Profile Reward orientation Team orientation Innovation Easy-goingness Procedural Outcome orientation Customer orientation Stability Mean Squares Between Banks (df = 5) 40.834 37.523 29.883 54.186 35.864 47.327 32.819 45.215 F Ratios* ICC 19.519 12.034 10.537 17.077 11.124 12.144 11.646 13.306 0.325 0.223 0.199 0.295 0.208 0.224 0.217 0.242 Within Banks (df = 63) 2.092 3.118 2.836 3.173 3.224 3.897 2.818 3.398 *All F’s are statistically significant (P <.001). VIKALPA • VOLUME 30 • NO 3 • JULY - SEPTEMBER 2005 45 Table 4: Results of Correlation Coefficients between Individual Preferences and Organizational Culture Values Bank 1 (n=23) 0.09 0.37 -0.12 0.03 0.11 -0.29 0.07 -0.06 0.05 0.11 0.13 0.18 -0.25 0.17 0.29 0.21 -0.11 0.08 0.10 -0.03 0.09 -0.23 0.03 Bank 2 (n=28) Bank 3 (n=32) Bank 4 (n=22) Bank 5 (n=16) Bank 6 (n=14) 0.11 0.13 0.14 0.07 -0.19 0.05 0.03 0.18 -0.06 0.09 0.14 0.10 -0.07 -0.05 0.11 0.13 -0.08 0.07 0.09 -0.01 0.03 0.06 0.11 0.27 -0.13 0.12 0.26 0.10 0.13 0.07 0.04 0.11 -0.18 -0.02 0.06 0.21 0.09 -0.29 0.07 -0.11 0.13 0.05 0.18 0.04 0.10 -0.02 0.09 0.25 0.36 -0.42 0.08 0.11 -0.20 0.06 0.09 0.05 -0.11 0.29 0.31 -0.05 0.53 0.11 0.06 0.18 0.21 0.57 0.02 0.19 0.05 0.48 0.31 0.05 0.44 0.37 0.39 0.09 -0.46 0.05 0.48 -0.24 0.07 0.23 0.54 0.47 0.11 0.31 0.08 0.63 0.18 0.71 -0.50 0.18 0.12 0.54 -0.25 0.57 0.48 0.13 0.10 0.74 0.46 0.12 0.18 0.73 0.62 0.08 -0.48 -0.06 0.73 0.19 0.12 -0.64 the relatively senior employees herein called as firm informants for each firm. Then these averaged profiles were correlated for ascertaining the overall correlation. Overall, banks 5 and 6 show a near strong person-culture fit score whereas bank 4 has a moderate score as revealed by Table 5. Person-culture Fit and Socialization Process in Organizations The results as depicted in Table 6 reveal that banks 5 and 6 are high ( X 5 = 60.91; X 6 = 62.56) on socialization while bank 4 has a medium level of socialization score ( X 4 =39.20) as per the Pascale (1985) scale. Banks 1 and 3 are just above the level of weak socialization score ( X 2 = 26.27, X 3 = 28.37) and bank 2 ( X 2 = 18.69) is very weak on socialization score as per the aforementioned scale. Comparative scores of person-culture fit and socialization scores of all the banks contained in Table 7 support hypothesis 2 that banks high on socialization score will 46 experience high value congruency. Dimensionality of Organizational Commitment Factor analysis using principal component analysis with varimax rotation method was performed on a 12-item commitment scale (Table 8). Out of 12 items, nine items with loadings greater than 0.40 were retained. After a scree test, two factors with eigen values greater than 1.0 emerged. These factors labelled as normative and instrumental commitment are somewhat consistent with the recent findings (O’Reilly, Chatman and Caldwell, 1991; O’Reilly and Chatman, 1986). Five items, representing commitment based on the acceptance of organizations’ values, defined factor 1 as normative commitment. Factor 2 — instrumental commitment — was defined by four items describing commitment based on exchange or in response to specific rewards. Using the results depicted in Table 8, two factor scores were computed for each respondent for subsequent analysis. PERSON - CULTURE FIT Table 5: Results of Overall Correlation Coefficient between Individual Preferences Profile and Firm Profile (Person-culture Fit) Bank 1 Bank 2 Bank 3 Bank 4 Bank 5 Bank 6 0.12 0.09 0.14 0.53 0.69 0.73 Bank 2 Bank 3 Bank 4 Bank 5 Bank 6 18.69 28.37 39.20 60.91 62.56 Table 6: Mean Bank Socialization Scores Bank 1 26.27 Table 7: Comparative Results of Bank Value Congruency and Socialization Scores Items Person-culture fit score Socialization score Bank 1 Bank 2 Bank 3 Bank 4 Bank 5 Bank 6 0.12 26.27 0.09 18.69 0.14 28.27 0.53 39.20 0.69 60.91 0.73 62.56 Person-culture Fit (Value Congruency) and Employee Commitment Correlation coefficients between person-culture fit and employee commitment was computed separately for normative and instrumental factors of commitment scale as shown in Tables 9 and 10 respectively. It is important to note that banks 4, 5, and 6 which were found high on value congruency and socialization scores show significant correlation (r4= -0.16, P <0.05), (r5 =0.22, P <0.01) and (r6=-0.21, P<0.01), between person-culture fit and normative commitment. Person-culture fit was also found significantly related to instrumental commitment for bank 4 (r=-0.16). However, with respect to banks 1, 2, and 3, the tables reveal that there was no significant relationship between person-culture fit and normative or instrumental commitment. The results, therefore, support hypothesis 1 that high value congruency will be positively related to employee commitment. RESULTS IN THE LIGHT OF CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH The results of this study, on the whole, support the assessment of validity of person-culture fit based on value congruency. Further, they suggest that the organizational culture profile depicts reasonable reliability and is organizationally useful. The cultural values of individual preferences (Table 1) and firm descriptions (Table 2) also appear to be comparable. The results also suggest that person-culture fit may provide meaningful insights into individual adjustments to organizations (Louis, 1980; O’Reilly, Chatman and Caldwell, 1991). The correlations in Table 9 bears testimony to this fact. Interestingly, high value congruency in banks is found significantly related to normative, value-based commitment but not instrumental, compliance-based commitment except in bank 4, where personculture fit is found related to both normative as well as instrumental commitment. This indicates that employees were committed to the organization because of the similarity between their own values and those of the organizations they worked in. Caldwell, Chatman and O’Reilly (1990) showed that normative commitment is often associated with firms with strong cultures. Researchers have suggested that high commitment and Table 8: Results of Factor Analysis of Commitment Scale (n=135) Items Normative What this organization stands for is important to me 0.59 If the values of this organization were different, I would not be as attached to this organization 0.62 How hard I work for the organization is directly linked to how much I am rewarded 0.12 In order for me to get rewarded around here, it is necessary to express the right attitude -0.04 Since joining this organization, my personal values and those of the organization have become more similar 0.61 My private views about this organization are different from those I express publicly -0.28 The reason I prefer this organization to others is because of what it stands for, its values 0.67 My attachment to this organization is primarily based on the similarity of my values and those represented by the organization 0.57 Unless I am rewarded for it in some way, I see no reason to expend extra effort on behalf of this organization 0.23 Eigen values 2.03 Proportion of variance accounted for 22.51 VIKALPA • VOLUME 30 • NO 3 • JULY - SEPTEMBER 2005 Instrumental 0.12 0.28 0.43 0.67 0.34 -0.78 -0.17 0.23 -0.64 1.94 21.58 47 Table 9: Results of Coefficient Correlations between Person-culture Fit and Normative Commitment r P Bank 1 Bank 2 Bank 3 Bank 4 Bank 5 Bank 6 0.09 n.s. 0.10 n.s. 0.14 n.s. -0.16 0.05 0.22 0.01 -0.21 0.01 Table 10: Results of Correlation Coefficients between Person-culture Fit and Instrumental Commitment r P Bank 1 Bank 2 Bank 3 Bank 4 Bank 5 Bank 6 0.03 n.s. 0.11 n.s. -0.09 n.s. 0.28 0.01 -0.06 n.s. 0.12 n.s. satisfaction are outcomes of person-organization fit (Kilman, Saxton and Serpa, 1986; Ouchi and Wilkins, 1985). Except for bank 4, instrumental commitment is not found significantly related to person-culture fit. These results showing lack of significant correlation between value congruency and instrumental commitment should not be taken as a surprise owing to the fact that our measures of congruence are predicated on a fit between individual preferences and organizational values rather than on the specific attributes of extrinsic rewards (Meyer and Allen, 1984). Posner, Kouzes and Schmidt (1985) found that value congruence between managers and their organizations affected a number of individual level outcomes (e.g., personal success, intention to remain with the organization, understanding of the organizations’ values, etc.). Taking school children as subjects by individually asking them to report their own values as well as the values of their schools, Feather (1979) too found that value congruence between school children and their schools was positively related to the children’s happiness and satisfaction. Organizational culture values have been found related to retention and turnover of employees by some other researchers as well. For instance, Kerr and Slocum (1987) and Kopelam, Brief and Guzzo (1990) argued that the variation in employee retention across organizations could be related to organizational culture values. They further suggested that various human resource strategies including selection and placement policies, promotion and development procedures, and reward systems hinged upon organizational culture values. It may be inferred from the above research that person-culture fit (value congruency) has predictive validity but as Sheridan (1992) noted, there has been less progress in comparing cultural effects on employee behaviour across organizations. Future researchers, therefore, need to further test the usefulness of the personculture fit notion with reference to its relationship with 48 employee behaviour in cross but homogenous organizational contexts to arrive at some meaningful conclusions. Another important finding is that organizations with high scores on socialization are also high on value congruency (Table 7). A number of researchers have shown that through socialization processes, managers can attempt to foster better employee understanding of organizational values, norms, and objectives (Kanter, 1988; Van Maanen and Schien, 1979). Prakash (1995) reported that an optimum level of fit between individual and organizational values was possible through socialization whereby the values of the members of an organization were sought to be integrated with the values of the organization. Reichers (1987) observed that most organizations encouraged their members to think and behave in consonance with its goals and espoused values. Chatman (1991) showed that in the first year of an employee’s recruitment, socialization experiences contributed significantly to changes in the person-organization fit. According to him, the person-organization fit is created, maintained, and changed during membership. Authors such as Mortimer and Lorence (1979) and Kohn and Schooler (1978) showed that occupational socialization affected individual characteristics. Organizational socialization is, therefore, believed to similarly influence individual values. Some specific activities have also been found responsible for promoting person-organization fit in the past research. Louis (1990) proposed that interaction with members facilitated sense-making, situation identification, and acculturation among recruits. This interaction was argued by some (Louis, Posner and Powell, 1983) to occur during firm-sponsored social activities and mentor programmes where recruits seized the opportunity of establishing rapport and relation with senior members. In this context, Terborg (1981) suggested that greater integration and interaction allowed new recruits to emulate their firms’ incumbents as refPERSON - CULTURE FIT erence points for their actions. Moreover, he asserted that, through mentor programmes, new recruits gather the required information about the organizations’ espoused values and historical contexts. Perceptions held by organizations’ members regarding how strong a firm is on socialization also influence person-organization fit. Research indicates that when members perceive their organization as having intensive socialization practices, they are more committed to organizational values (Caldwell, Chatman and O’Reilly, 1990). The above research evidence clearly supports the findings of this study. However, the results of this study need to be taken with caution because the study is correlational. In addition, we did not control for socialization to assess if value congruency was a result of socialization or some other contingency variables. It is, therefore, recommended that future research tests for causalty. IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY To retain customers and stay competitive in the globalized business world, organizations in the service sector, especially banks, need to make customer perception of service quality a priority. According to researchers like Schneider, White and Paul (1998), the customer who holds positive perception regarding the organiza- tions’ service quality is likely to remain a customer of that organization. It is to the benefit of these organizations that the current customer provides a potential base for cross-selling. Also, it is less expensive for them to keep a current customer than to gain a new one (Rust and Zahorik, 1993). Therefore, a high performing culture requiring high employee involvement (Lawler, Mohrman and Ledford, 1995) is needed by today’s organizations to fulfil the ever changing customer priorities and expectations. In fact, some argue that an organization’s competitive advantage depends on the degree to which it effectively manages human resources by ensuring that both the organization’s and the individual’s expectations and values are similar (Pfeffer, 1995; Rousseau, 1995). Moreover, research indicates that socialization helps to ensure that both the organization’s and the individual’s needs are met (Major, 2000) and also that socialization practices are key to both transmitting and perpetuating organizational culture (Louis, 1990; Trice and Beyer, 1993). Further, some researchers argue that the strength of culture is the strength of commitment (Virtanen, 2000). Thus, in the light of the present study and earlier research evidences, banks, especially in the public sector, need to pay due attention to socialization practices which are expected to result in strong cultures and hence strong employee commitment. REFERENCES Albert, S and Whetten, D (1985). “Organizational Identity,” in Cummings, L L and Staw, B M (eds.), Research in Organizational Behaviour, Volume VII, 263-295. Bartko, J J (1976). “On Various Intraclass Correlation Reliability Coefficients,” Psychological Bulletin, 83(5), 762-765. Boyd Jr., H W; Westfall, R and Stasch, S F (1996). Marketing Research — Text & Cases (Seventh Edition), Delhi: AITBS Publications and Distribution. Bravermann, H (1974). Labour and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century, New York: Monthly Review. Brown, A (1995). Organizational Culture, London: Pitman. Buchanan, B (1974). “Building Organizational Commitment: The Socialization of Managers in Work Organizations,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 19(4), 533 546. Caldwell, D and O’Reilly, C (1990). “Measuring Person-job Fit Using a Profile Comparison Process,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(6), 648-657. Caldwell, D; Chatman, J and O’Reilly, C (1990). “Building Organizational Commitment: A Multi-firm Study,” Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(3), 245-261. Calori, R and Sarnin, P (1974). “Corporate Culture and VIKALPA • VOLUME 30 • NO 3 • JULY - SEPTEMBER 2005 Economic Performance: A French Study,” Organisation Studies, 12, 49-74. Chatman, J (1989). “Improving Interactional Organizational Research: A Model of Person-Organization Fit,” Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 333-349. Chatman, J (1991). “Matching People and Organizations: Selection and Socialisation in Public Accounting Firms,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 459-484. Chatman, J A and Jehn, K A (1994). “Assessing the Relationship between Industry Characteristics and Organizational Culture: How Different can You be?” Academy of Management Review, 37(3), 522-553. Deal, T and Kennedy, A (1982). Corporate Cultures, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Denison, D and Mishra, A (1995). “Toward a Theory of Organizational Culture and Effectiveness,” Organizational Science, 6(2), 204-233. Feather, N T (1979). “Human Values in the Work Situation: Two Studies,” Australian Psychology, 14, 131-141. George, W and Marshall, C (1984). Developing New Services, Chicago: American Marketing Association. Gordon, G G and DiTomaso, N (1992). “Predicting Corporate Performance from Organizational Culture,” Journal of Management Studies, 29(6), 783-798. 49 Hofstede, G (1998). “Identifying Organizational Sub-cultures: An Empirical Approach,” Journal of Management Studies, 35(1), 1-12. Holland, J L (1985). Making Vocational Choices (Second Edition), Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. James, L R (1982). “Aggregation Bias in Estimates of Perceptual Agreement,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(2), 219-229. Joyce, W F and Slocum, J W (1984). “Strategic Context and Organizational Climate,” in Schneider, B (ed.), Organizational Climate and Culture, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Kanter, R (1988). “When a Thousand Flowers Bloom: Structural, Collective, and Social Conditions for Innovation in an Organization,” in Staw, B B and Cummings, L L (eds.), Research in Organizational Behaviour-Volume 10, Greenwich, C T: JAI Press, 169-211. Kanungo, R N and Mendonca, M (1994). “Culture and Performance Improvement,” Productivity,35(3), 405-417. Kelman, H C (1958). “Compliance, Identification, and Internalization: Three Processes of Attitude Change,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2, 51-60. Kerr, J and Slocum, J W (1987). “Managing Corporate Culture through Reward Systems,” Academy of Management Executive, 1(2), 99-108. Kilman, R; Saxton, M and Serpa, R (1986). “Issues in Understanding and Changing Culture,” in Newstorm, J M and Davis, K (eds.), Human Behaviour at Work (Eighth Edition), New York: McGraw Hill. Koene, B A S (1996). “Organizational Culture, Leadership and Performance in Context: Trust and Rationality in Organizations,” unpublished doctoral dissertation, Netherlands, Maastricht: Rijksuniversiteit Limburg. Kohn, M L and Schooler, C (1982). “Job Conditions and Personality: A Longitudinal Assessment of their Reciprocal Effects,” American Journal of Sociology, 87, 1257 1286. Kopelam, R E; Brief, A P and Guzzo, R A (1990). “The Role of Climate and Culture in Productivity,” in Schneider, B (ed.), Organizational Climate and Culture, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 282-318. Lawler III, E E; Mohrman, S A and Ledford Jr., G E (1995). Creating High Performance Organizations: Practices and Results of Employee Involvement and Total Quality Management in Fortune 1000 Companies, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Louis, M (1980). “Surprise and Sense-making: What Newcomers Experience in Unfamiliar Organizational Settings,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(2), 226-251. Louis, M R (1990). “Newcomers as Lay Ethnographers: Acculturation during Organizational Socialization,” in Schneider, B (ed.), Organizational Climate and Culture, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Louis, M R; Posner, B Z and Powell, G N (1983). “The Availability and Helpfulness of Socialization Practices,” Personnel Psychology, 36(4), 857-866. Magnet, M (1993). “Good News for the Service Economy,” Fortune, 127(9), 46-52. Major, D A (2000). “Effective Newcomer Socialization into High-performance Organizational Cultures,” in Ashkanasy, N M; Wilderom, B P M and Peterson, M F (eds.), Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate, New Delhi: Sage Publications. 50 Meyer, J P and Allen, N J (1984). “Testing the Side-bet Theory of Organizational Commitment: Some Methodological Considerations,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(3), 372-378. Mowday, R T; Steers, R M and Porter, L W (1979). “The Measurement of Organizational Commitment, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 28, 224-247. Nazir, A N (2000). “Organizational Culture and its Relationship with Employee Commitment,” unpublished doctoral dissertation, New Delhi: University of Delhi. Norman, R (1984). Service Management: Strategy and Leadership in Service Businesses, New York: Wiley. O’Reilly, C and Chatman, J (1986). “Organizational Commitment and Psychological Attachment: The Effects of Compliance, Identification, and Internalization of Prosocial Behaviour,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 492499. O’Reilly, C; Chatman, J and Caldwell, D (1991). “People and Organizational Culture: A Q-Sort Approach to Assessing Person-Organization Fit,” Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 487-516. Ouchi, W and Wilkins, A (1985). “Organizational Culture,” in Turner, R (ed.), Annual Review of Sociology, 11, Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews, 457-483. Pascale, R (1985). “The Paradox of Corporate Culture: Reconciling Ourselves to Socialization,” California Management Review, 27(2), 26-41. Pathak, R D; Rickards, T and Pestonjee, D M (1996). “Culture and its Consequences for Creativity and Innovation Management,” Productivity, 37(1), 84-93. Peters, T J and Waterman, R H (1982). In Search of Excellence, New York: Harper. Pfeffer, J (1995). “Producing Sustainable Competitive Advantage through the Effective Management of People,” Academy of Management Executive, 9(1), 55-72. Posner, B Z; Kouzes, J M and Schmidt, H (1985). “Shared Values Make a Difference: An Empirical Test of Corporate Culture,” Human Resource Management, 24(3), 293-310. Prakash, A (1995). “Organizational Functioning and Values in the Indian Context,” in Henry, S R; Kao, Durganand S and Ng, Sek-Hong (eds.), Effective Organizations and Social Values, New Delhi: Sage Publications. Reichers, A E (1987). “An Interactionistic Perspective on Newcomers’ Socialization Rates,” Academy of Management Review, 12(2), 278-287. Rousseau, D M (1995). Psychological Contracts in Organizations: Understanding Written and Unwritten Agreements, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Rust, R and Zahorik, A (1993). “Customer Satisfaction, Customer Retention, and Market Share,” Journal of Retailing, 69(2), 193-215. Schneider, B (1987). “The People Make the Place,” Personnel Psychology, 40, 437-453. Schneider, B; Gunnarson, S K and Niles-Jolly, K (1994). “Creating the Climate and Culture of Success,” Organizational Dynamics, 23(1), Summer, 17-29. Schneider, B; White, S S and Paul, M C (1998). “Linking Service Climate and Customer Perceptions of Service Quality: Test of a Causal Model,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 150-163. Sheridan, J E (1992). “Organizational Culture and EmploPERSON - CULTURE FIT yee Retention,” Academy of Management Journal, 35(5), 1036-1056. Stryker, E and Serpe, R (1982). “Commitment, Identity Salience, and Role Behaviour: Theory and Research Example,” in Ickes, V and Knowles, E (eds.), Personality Roles and Social Behaviour, New York: Springar-Verlag, 119-218. Terborg, J R (1981). “Interactional Psychology and Research on Human Behaviour in Organizations,” Academy of Management Review, 6(4), 589-600. Trice, H M and Beyer, J M (1993). The Cultures of Work Organizations, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Van Maanen, J and Schien, E H (1979). “Towards the Theory of Organizational Socialization,” in Staw, B (ed.), Research in Organizational Behaviour–Volume 1, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 209-264. Virtanen, T (2000). “Commitment and the Study of Organizational Climate and Culture,” in Ashkanasy, N M; Wilderom, B P M and Peterson, M F (eds.), Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate, New Delhi: Sage Publications. Wilderom, B P M; Glunk, U and Maslowski, R (2000). “Organizational Culture as a Predictor of Organizational Performance,” in Ashkanasy, N M; Wilderom, B P M and Peterson, M F (eds.), ibid. Nazir A Nazir is Associate Professor in the Department of Commerce, University of Kashmir, Srinagar. A Ph. D. from the Faculty of Management Studies, University of Delhi, he has contributed articles in reputed journals including the Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, Indian Journal of Training and Development, etc. He was the Associate Editor of the journal titled, The Business Review during 2000–2002. He is also associated with professional bodies such as HR India and IIPA, Delhi. e-mail: na_nazir2000@yahoo.co.uk Effective innovations start small. They are not grandiose. They try to do one specific thing. It may be to enable a moving vehicle to draw electric power while it runs along elementary as putting the same number of matches into a matchbox (it used to be fifty), which made possible the automatic filling of matchboxes and gave the Swedish originators the idea of a world monopoly on matches for almost half a century. Grandiose ideas, plans that aim at revolutionizing an industry, are unlikely to work. Peter Drucker VIKALPA • VOLUME 30 • NO 3 • JULY - SEPTEMBER 2005 51