Beyond the Ghosts - Historians for Britain

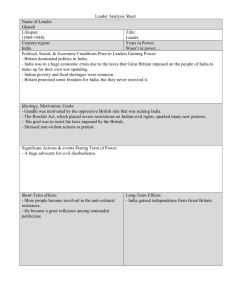

advertisement

Historians for Britain is an independent, non-partisan group established by Business for Britain, to represent the historians and academics who believe in a renegotiation of Britain’s relationship with the European Union, backed up by an In/Out referendum. The group was founded in July 2013 when twenty-two of Britain’s leading historians wrote to The Times to throw their support behind the campaign for a renegotiation of Britain’s EU membership. Signatories included Professor David Abulafia, Lord Lexden and Professor Robert Tombs. Historians for Britain aims to achieve its objectives via quality research and set-piece seminars and lectures, which will demonstrate that leading historical thinkers have serious reservations about Britain’s current relationship with the EU and want a better deal for our country. Members of the HfB Board include: Professor David Abulafia (Chairman) – Professor of Mediterranean History, Cambridge University Dr Sheila Lawlor – Director, Politeia Dr Andrew Roberts – Author and historian Dr David Starkey – Honorary fellow, Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge University The views expressed in this essay are those of the author alone and not those of Historians for Britain or Business for Britain. The cover is by John Henry Fuseli/ Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741-1825), an Anglo/Swiss artist. “The Nightmare” was his most famous painting. Fuseli painted four variations of the theme. This is the second, of 1790-91. Oil on canvas, 77 x 64 cm. It is at the Goethe Museum in Frankfurt. An abbreviated version of this essay will be published in the Institute for Economic Affairs book on Britain and the EU in 2016 Beyond the Ghosts 2 Foreword In the essay that follows Professor Gwythian Prins raises some fundamental questions about how the European Union has developed out of its predecessors, and about where it might be going. Even the most ardent Europhiles would have to agree with Professor Prins that the European Union is in deep crisis, over the Eurozone, Schengen and other strains; as currently constituted, it is unpopular with large sections of the population in several of the largest member states. Professor Prins shows with great clarity and expertise how the decision-making process in the Union is incompatible with the political traditions of the United Kingdom. He demonstrates that the only way forward for the Union is radical change, in place of the continuing complacency of the Eurocrats. Britain might want to be part of a reformed trading zone; but anyone thinking about whether we should continue to be part of the present-day Union needs to reflect on Gwythian Prins’s brilliant insights. David Abulafia Cambridge University 3 Troubled union The European Union was fifty eight in March. It did not bid farewell to middle age in the last months of 2015 with ease, self-confidence and optimism for the future, but in a bout of weariness, self-doubt, and depression. Embattled remarks by Commission President Juncker suggested that plainly he was feeling that the EU was the future, once. The Eurozone, of which Britain is not part, continues to be the world economic area which, taken as a whole, is most dogged by poor performance despite mounting interventions by the European Central Bank to stimulate it. The EU now accounts for less than half of Britain’s trade and main indicators point to further diminution of that proportion. The ‘Euro’ common currency and the ‘Schengen’ open borders zone both fractured badly in 2015. President Juncker described the Schengen Zone as “semi-comatose,” adding that he believed that the single currency could not survive Schengen’s collapse. They are the two concrete achievements most prized by enthusiasts for the ‘project’ of the European Union: the strange butterfly which emerged from the chrysalis of the European Economic Community in 2007 at signature of the Lisbon Treaty. This essay will describe the main features of the history of that ‘project.’ Often obscured and rarely presented in the round, it is a history that has been at the same time tragic and heroic. The British people need to understand it clearly before deciding whether or not to remain part of the EU because that history explains why the EU has the type of institutions that it has and why it behaves today as autocratically as it does. The one-size-fits-all currency has crucified its southern members economically, has deformed their political cultures and has stressed fragile democracies in dangerous ways, with the Greek July Crisis marking a nadir. But even socially and technologically advanced Finland, which is one of the most competitive Eurozone economies, is trapped by the fixed exchange rate and the Stability Pact; and therefore its Parliament will debate leaving the Euro in 2016. However, in November 2015 after weeks of wrangling, the eventual triumph of the triple-left alliance of socialists, communists and the greenish Left Bloc in Portugal, over which (unlike the Greek government) the ECB has no leverage, already guarantees relentless continuing tension in the Eurozone. The Euro crisis will not go away, because the Eurozone’s structural incoherence means that it cannot. In 2015, the previously undisputed right of passport-free travel across the Schengen Zone (of which Britain is also not a member) has been blown apart – quite literally – by the terrorism of the Da’esh. Its home-grown perpetrators, many of them internet-savvy children, banlieusards of the grim ghettos of France and Belgium, exploited the migration crisis of the summer to slip back into Europe from their training camps in the Da’esh-controlled spaces of what were once parts of Syria and Iraq. Passport-free travel was created for a more carefree age that fanatical Islamist terrorism and mass migration across the Mediterranean have ended. That migration crisis was aggravated by Chancellor’s Merkel’s rash invitation (later, too late, rescinded), which provoked another flood of people; and this in turn further soured already bitter eastern European views of the EU, when, by diktat of qualified majority voting, Brussels imposed quotas of largely middle-eastern and Muslim refugees upon them, against their will. The old familiar call to show ‘European solidarity’ sounded nastily Soviet and rang hollow in eastern European ears. It has been a summer and autumn of building fences and reopening Beyond the Ghosts 4 border control posts, first in south east Europe and the Balkans and later on between France and Belgium. The Øresund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden, iconic to fans of the eponymous “Scandi-noir” thriller, may soon acquire checkpoints too. The British public has watched all this with open dismay and some private relief from behind borders where passports are still checked and which are defined geopolitically and psychologically by the English Channel. This is the unhappy state of the Union of which Britain is an awkward and institutionally eccentric member as we have always been since joining. Should we continue? Should we change ourselves fundamentally to fit the EU’s agenda or should the EU change fundamentally to fit ours? Or should we just leave? What is it in our best interests and the best interests of our children to do? A referendum will be held on these questions. It appears that the Prime Minister wishes this to be in 2016 if possible. But how to decide? What issues should weigh most heavily? Above all we really need to know the balance of advantage and disadvantage for Britain’s global influence because upon that depends both our future wealth and our national security. Does the EU nourish or consume it? In an important recent Whitehall study Britain has been rightly described as “a ‘soft’ power superpower.” That power derives from the very pith of who we are; and we are Europeans whose destiny has always been with – but not of – those of the continental nations. Therefore just as tall trees need strong roots, an accurate grasp of our history matters vitally for our future. Likewise, the EU’s very nature, as well as its prospects, also derive from its unusual moment in the long history of Europe. Here an important distinction must be made and underlined. The EU is not Europe. The EU is an historical episode only. Europe is a geopolitical entity: an enduring kaleidoscope of peoples, cultures and places. It is mischievous to conflate them as politicians frequently do. Therefore we shall take a long view of our historical engagement with Europe and also of the EU’s history too. To weigh the value to Britain of participation in the ‘project’ of European union, the most familiar scales used are calibrated for economic costs versus benefits. They have been the longest in service. Although, over forty years ago, Edward Heath suggested that amplification of foreign policy influence was another leading benefit of joining, and Tony Blair likes to say that ‘the case for Europe is power, not peace’, today those promoting continuation of British participation continue to favour and advocate an economics test first and foremost, although one now couched more in vague terms of fear of change than one based on a track record of palpable advantage. Given how lacklustre the EU’s present and future economic prospects are, this seems to be an odd hill on which to choose to plant your fl ag; but old habits are hard to change. Those who make this case tend to be the same people who argued with equally implacable certainty that Great Britain would be doomed if we failed to join the ‘Euro’ common currency; and we know how that worked out. Quantified in hard figures, economic cost/benefit is relatively easier to weigh and then judge than the metrics that matter most for judging national influence and interests world-wide. There are some technical tests that can be applied to the processes of diplomacy but they are not the most important tests. So most of what follows discusses the deeper, less tangible, logically prior and decisive considerations. 5 How best to nourish British interests: two paradoxes We shall explore two paradoxes. Where our interests coincide - which sometimes they do but not always - close British engagement with European nations on security, defence and foreign policy is greatly in the British national interest. It has always been so and is especially so in today’s starkly menacing world. But how is that to be safely achieved? The world-wide terror campaign of the Da’esh bloodily closed an era in European history during 2015. With their leading aims of fomenting mistrust of all Muslims by all non Muslims, collapsing tourist economies, driving westerners from the Middle East and Africa and thereby driving impoverished, culturally isolated and resentful Muslims into their arms, the Da’esh started its work in earnest with the Charlie Hebdo attack and the attack on a kosher supermarket in Paris. This was soon followed by the pornographic violence of filmed mass beheadings of Egyptian Coptic Christians in February, the attempted attack on tourists at Luxor in June (which is thought to have had Da’esh involvement) and then, on 26 June, the killing of mainly British tourists on the beach at Sousse in Tunisia. Da’esh attacks gained an accelerated tempo in the autumn, claiming credit for the murder of ordinary random victims on the streets in Lebanon and of Russian tourists in a plane over Sinai (whether or not they perpetrated it). Then in Paris on 13 November the Da’esh produced the worst loss of life in France at the hands of armed enemies since the Second World War with professionally executed multiple simultaneous commandoterrorist attacks. President Hollande declared that the country was at war. So it was no surprise that France therefore led the successful efforts at the UN Security Council to obtain a unanimous ‘all necessary means’ resolution to crush the Da’esh. France also forced the EU to accept the de facto suspension of the uncontrolled free movement of people within the Schengen Zone which France had requested but the EU had refused after the Charlie Hebdo killings in Paris on 7 January. This time the French demand was implacable. Extreme national emergency violently exposes all contradictions and cherished illusions and cruelly strips them away. Trans-national co-operation is vital in combatting the pan-European threat of unconditional millenarian Islamist terrorism, which is both physically violent and culturally corrosive. It is also essential in facing down the resurgent malevolence of Putin’s demographically and economically stricken Russia. Despite an economy that contracted 4.6% in 2014 and with sharply falling currency reserves, military spending increased strongly (8.1% to $84bn in 2014 and 15% in 2015). This money has bought root and branch military reforms. After ruthlessly cutting away the dead wood of the inherited Soviet armed forces, there has been vigorous regeneration through creation of a new, young, devoutly religious (Russian Orthodox) officer corps and by comprehensive modernisation of equipment. These have been exercised in aggressive deployments and used in successful and sophisticated ‘hybrid’ modes of operation, including the active use of fifth, sixth and seventh columnists, starting in the South Ossetia and Abkhazia districts of Georgia in 2008. When the West did not deter him there, Putin progressed to destabilisation and dismemberment of Ukraine at the same time offering support and encouraging disaffection in south-eastern EU member states. He is now probing the Baltic region and deploying to sustain Assad in Syria. Such facts on the ground support the view that Putin’s self-evident if unspoken goal is to rip up the spheres of Beyond the Ghosts 6 influence agreement made between Churchill and Stalin in the Kremlin on 9 October 1944 (the so-called ‘percentage deal’) that gave first form to the détente which governed East/West relations until 21 March 2014. On that day, again in the Kremlin and in clear breach of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum which had guaranteed Ukraine’s territorial integrity when it surrendered its nuclear weapons, President Putin signed the instrument ratifying the incorporation of Crimea into the Russian federation. Presumably to emphasise their powerlessness, Putin’s chosen date coincided with a meeting of EU Heads of State in Brussels.2 Mr Obama has unfortunately given consistently limp leadership to the free world during his Presidency. His domestically divisive enthusiasms, his repeated indecision in crisis, and his sometimes feckless passivity (chronically so over the fate of Syria since 2011) have left open opportunity both for the growth of the Da’esh and of Putin’s revanchism. Therefore we do not have the American lead to which we have grown accustomed and that has made co-operation among western and especially European nations the highest of all political priorities as 2015 ends. This co-operation between nations is, as it always has been in emergency, derived from their own sovereign will and powers, and not as a result of an appeal to supranational authority. Ironically, because of the one way ratchet gearing which was built into the Project of European Union from its conception, this co-operation cannot occur safely under the status quo of the Lisbon Treaty and the agents which it created (the EU’s ‘Common Foreign & Security Policy’ (CFSP) and the ‘European External Action Service’ (EEAS)). Only fundamental amendment of the Lisbon Treaty removes that ratchet; and this is the first framing paradox. The ratchet is why French politicians often repeat that there cannot be a “Europe à la carte.” They are right. The EU treaties are a legal strait-jacket as the German-born Labour MP Gisela Stuart reminded the Minister for Europe. Reacting to his statement on the Cameron/Osborne re-negotiation, she asked him rhetorically in the House of Commons on 10 November 2015 which treaty provision he would use to repatriate powers to Parliament from Brussels and, knowing better than most MPs that the answer is that there is none, “…if he does not have one, will he negotiate a new one?” It is also why the Cameron government’s 2015 negotiation tactic was back to front. He and his Chancellor appear to have asked what was the most the others could live with. The Prime Minister’s letter to Donald Tusk, the President of the EU Council, in which he was reluctantly compelled by the other EU members to disclose his four demands, made such mild requests that it caused one of the most influential Conservative backbenchers, the Chairman of the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Select Committee, to ask incredulously in the same House of Commons session with the Minister for Europe, “Is that it? Is that the sum total of the government’s position in this renegotiation?”3 As this essay goes to press it seems that the Prime Minister will not achieve even the four requests that he made. 2 3 Churchill, (1954), p.198; Petraitis (2012). Seventh columnists are individuals suffering from the Dunning-Kruger effect: a psychological syndrome describing people who greatly overestimate their actual potential competence at a task and who collapse into indecision or erratic behaviour under pressure. Reformed Russian strategy seeks to identify and, with the help of Fifth and Sixth columnists, to cause such people to be promoted into positions of power in democratic states that Putin regards as hostile to his interests. Once installed, they can then be squeezed to effect what the Russian doctrinal literature calls ‘velvet sabotage’ in Russia’s interests but without direct Russian action. It is a cynically intelligent, elegantly economical and deadly serious form of ‘hybrid’ warfare that has certainly been applied in Russia’s ‘near abroad’. Petraitis (2015) Hansard, 10 November 2015 7 In any case that tactic cannot deliver Britain’s minimum requirements. With a body constituted as the ‘EU’ is, the starting position must be to declare an intention to leave – and to mean it - unless Britain recovers full sovereignty by negotiated agreement and basic treaty change. A form of co-operation that by its nature does not imperil our national security can only be safely achieved once Britain has either been totally released from CFSP/EEAS by European agreement – and given the nature of the machine, total must be total - or removed from that power by the referendum vote of its people. The ‘European idea’ died a decade ago for most Europeans, especially south of the Alps. So firm negotiating should be much easier than before the Euro began to poison the Project. By being uncompromising, a second and virtuous paradox appears. By forcing a general abandonment of the goal of ‘ever closer union’ and of consequent material political processes engaged to achieve it, and by demanding repatriation of sovereign powers to Parliament, British success might also save the free trade area for others too, which otherwise might be lost in the current crumbling of the Project. If Prime Minister Cameron were to achieve this, Britain would once again have helped to save Europe from itself and it would be an act of statesmanship that would be on a par with those of Prime Ministers Churchill or Salisbury or of Foreign Secretary Castlereagh. Why the EU and its fears are older than you think The current Project was conceived in the horrors of the battlefield of Verdun during the Great War. It had its first flowering and shrivelling in the 1920s and it became a political reality in the wake of the Second World War. Therefore it is scarred to its core by the wars that gave birth to it. In 1950 after the Second World War, it seemed reasonable, even imperative, to neuter the nations of Europe. The French eminence grise of the Project, Jean Monnet (1888-1979), was a bureaucrat, inspired by that vision of a united Europe which Tennyson had expressed in words cherished by generations of world federalists: “Till the war-drum throbb’d no longer, and the battle-flags were furl’d/In the Parliament of man, the Federation of the world.”4 Arthur Salter, his friend and colleague also working at the League of Nations, was the Englishman who in 1931 wrote The United States of Europe: it is a book which sets out that shared vision in detail. Another close collaborator was Walter Hallstein, a German technocratic academic who believed in international jurisdiction as the morally superior successor to the laws of the nation states; and his priority is inscribed in the constitution for the European Court of Justice, prescribing travel towards ever closer union. Monnet, Salter and Hallstein were joined by Altiero Spinelli, a romantic communist who advocated a United States of Europe legitimised by a democratically elected European Parliament. In form but not substance that also has come into being with tepid and cooling public support. Such people were not isolated enthusiasts, but shared a sentiment widespread among the inter-war European elites. Its animator was Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi the charismatic leader of the Pan Europa movement. 4 Alfred Lord Tennyson, “Locksley Hall” 1835 Beyond the Ghosts 8 The culmination of frank utopian federalism was French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand’s proposal for a European Federal Union, which in May 1930 was summarily rejected in the same way that the Kellogg-Briand Pact proposal to outlaw war had been in 1928. The rebuff caused Monnet and his friends to reassess their tactics. They chose creeping federalism (the covert acquisition of ever more power without consent). By playing a constitutional game of Grandmother’s Footsteps with the unenlightened canaille, approaching the goal of federal union obliquely and enticing electorates with tasty a-political morsels at first, it could become – pouf! –an irrevocable fait accompli. This functionalist tactic is known as the ‘Monnet Method’.5 Irrevocability is the heartbeat of the process that expands the acquis communautaire: the unrepealable ‘Community inheritance’ of accumulating laws, policies and practices. The founders sought and obtained the support of popular political leaders like Konrad Adenauer, Robert Schuman and Alcide De Gasperi to translate Monnet’s Method into concrete political forms. One of Coudenhove’s ideas from the 1920s was to create a European coal and steel community. As ‘the Schuman Plan’ that became the initial step in 1951. Why this reckless sense of mission that justified playing such a game? Because they trusted no-one but themselves and least of all the common people. The Monnet generation was devastated by the Great War. It held the emperors, monarchs, autocrats and diplomats – the sleep-walkers – and the states which they ruled, responsible. Their bungling, they believed, had smashed the long peace for insufficient cause; and we might see why they felt that way.6 They surveyed the wreckage of Eurasia’s multinational imperial states. So too did Lenin and Rosa Luxembourg and an assortment of Balkan, Turkish and eastern European nationalists. All agreed that given their gigantic inequalities, their autocratic rule and their unreformability the breaking of these empires was deserved and we too might understand why they thought so. All agreed (as Rousseau once wrote) that ‘what can make authority legitimate?’ is the axiomatic question in politics; and certainly we should entirely concur with that.7 However, they came to wildly different conclusions about what should come next: from democidal communist revolution to national cultural revival to utopian cosmopolitanism.8 The USSR (deceased in 1991 after one human life-span) was product of the first reaction. Today’s ailing EU is the product of the third. Across the century, all that diversity and fear boiled down in the brains of the founding fathers into a generalised critique of the nation-state as pathological in principle, which it certainly is not. The success of the British nation-state, both in itself and as a global role model, must not be tarred with the trans-continental failures of Austro-Hungary or Russia, with the failures or fractures of the Balkan states, imperial and later Nazi Germany, Belgium or France.9 5 6 7 8 9 An English children’s game. One person (‘grandmother’) walks in front of a group of others who try to catch up with her to touch her without her seeing them coming. If ‘grandmother’ turns around, everyone freezes. Anyone caught moving by ‘grandmother’ is out. In the EU version, the people are ‘grandmother’ and the federal enthusiasts are trying to catch her without being noticed in time. For a more charitable assessment of such games see Carls & Naughton (2002) In light, most prominently and persuasively among the centenary books, of Clarke (2012) First quoted as his compass in Kissinger (1957) pp. 3-4, in subsequent books and most recently repeated in Kissinger (2014) ‘Democide’ is death at the hands of one’s own government. On Professor Rudi Rummel’s grim calculations it killed more people by human agency in the twentieth century than any other means. Rummel (1994) The matter is discussed from many angles by the contributors to Möhring & Prins (2013). Essays from across the political spectrum, in particular by Michael Gove and Frank Field, by Michael Ignatieff and Daniel Hannan, by Roger Scruton and Julian Lindley-French, explore and refute the accusation that the nation-state in any form is ineradicably ‘pathological’. The case for the prosecution is best made by the FCO’s licensed thinker at that time, Robert Cooper in Cooper (2003). Cooper’s view that it is in Britain’s interest to depart from its successful 400 year strategy for dealing with the Continent (pp 52-3, pp 138-51) is once more at the heart of the debate. 9 ‘With Europe but not of it … linked but not compromised’ To play Grandmother’s Footsteps with such momentous matters is to play with fire. Just such tactics threatened breakdown of trust in the anti-Napoleonic league, observed the British Foreign Secretary – one of our greatest - in 1820: In this Alliance [for which, today, read ‘EU’], as in all other human arrangements, nothing is more likely to impair, or even to destroy its real utility, than any attempt to push its duties and its obligations beyond the Sphere which its original conception and understood Principles will warrant … it never was … intended as an Union for the Government of the World, or for the Superintendence of the Internal Affairs of other States. (emphasis added) … It was never so explained to Parliament; if it had, most assuredly the sanction of Parliament would never have been given to it …10 In Castlereagh’s words, that is the nub of the British peoples’ complaint about the ‘EU’, having from the outset been led up the garden path about the federal purpose and one-way direction of the European project by Edward Heath and his associates. Heath was a Prime Minister haunted by the ghost of British decline (that he believed to be both inexorable and probably deserved) and at the end of his life he eventually revealed himself to be an openly self-confessed federalist. By their lack of candour with the electorate, he and his colleagues of similar views, who included Harold Macmillan, poisoned the wells of trust in our politics from that time to this. Each further step of European integration has advanced on the same principle, uni-directionally and steadily removing power from the nations and banking it in Brussels under the lock of the acquis communautaire, interpreting ‘subsidiarity’ to mean that Brussels decides what powers shall remain with the nations - which is the opposite of the usual meaning. The passerelle or ‘footbridge’ clause of the Maastricht Treaty increased the Council’s power to accelerate one-way transfers of power to Brussels. The meshing of this ratchet gearing (engrenage) is expressed in the goal of “Every Closer Union” and cannot be disengaged without exploding the Monnet project and mechanism. It applies to all areas. In foreign policy it has been under vigorous acceleration since the creation of the EU foreign policy (CFSP) and “External Action Service” by the thinly disguised EU Constitution (now known as the Lisbon Treaty signed in December 2007). The New Labour government objected to both CFSP and EEAS during negotiations on the draft constitutional treaty, only to be brushed aside and then eventually to capitulate entirely.11 In short, either the EU must change its very nature, or the British must leave the Project and revert to the script of Lord Castlereagh’s great Confidential State Paper of 5 May 1820, which served British foreign policy well for over a century. Winston Churchill memorably condensed 10 Viscount Castlereagh, Confidential State Paper, 5 May 1820, reproduced in Ward & Gooch (1923) pp 622-33 11 Open Europe (2007) pp.10-11 Beyond the Ghosts 10 its essential message in 1930, writing that, “we are with Europe but not of it. We are linked but not compromised.”12 In 1820 Castlereagh spelled out our objection in words that are exactly applicable to Britain today: The fact is that we do not, and cannot feel alike upon all subjects. Our position, our institutions, the habits of thinking, and the prejudice of our people, render us essentially different. We cannot in all matters reason and feel alike; we should lose the confidence of our respective nations if we did, and the very affectation of such an impossibility would soon render the Alliance [for which now read the EU] an object of odium and distrust … We must admit ourselves to be … a Power that must take our Principle of action, and our scale of acting, not merely from the Expediency of the Case, but from those Maxims which a System of Government strongly popular and national in its Character, has imposed upon us: We shall be found in our place when actual Danger menaces the System of Europe, but this Country cannot and will not act upon abstract and speculative Principles …13 Only Palmerstonian coalitions of the willing are worth having – that is to say coalitions of sovereign nations that share material interests in a concrete issue, since nations do not have permanent friends but do have permanent interests. There is nothing either insular or introspective about resumption of our historical norm.14 Frightening the horses: the transforming consequences of the Euro Enthusiasts for the Project dislike and rarely discuss this history. If confronted with it they tend to denigrate it as conspiracy theory. Nowadays that is harder to do because, during its short life, the rolling economic and social disaster of the hubristically named ‘Euro’ has lurched and barged its way to the centre of European affairs. Too hastily promoted by the French elite to counterbalance the crisis (for them) of German reunification, which meant that the sturdy German horse was threatening to unseat the skilful French rider (the phrase is General de Gaulle’s), the single currency experiment has culminated in the Greek crisis of July 2015. By year’s end the July Crisis had followed Jean Monnet’s prescription that “people only accept change when they are faced with necessity and only recognise necessity when a crisis is upon them. ”The so-called ‘Five President’s Report’ of 22 June 2015 was plainly another attempt in the 12 cit Leach (2004) p.25. Churchill was commenting on the rebuffed Briand Plan. 13 Historians have sometimes described Castlereagh as ‘non-interventionist’ in contrast to his successors; whereas this passage and Canning’s own words confirm a continuity which expresses Britain’s rooted geo-political interests to this day. This historiographic point is further discussed by Castlereagh’s most recent biographer in Bew (2011) pp 481-2 14 Andrew Roberts also stresses this point in his essay “British engagement with the continent of Europe” in (ed) Abulafia, (2015), pp 29-33 11 Monnet mode to use this Euro crisis to push for greater fiscal and hence political integration.15 Therefore a temporary “success” for the Project is likely by following the pattern of all previous EU crises: namely, on the German plan, a ruthless subordination of Greek sovereignty to the General Will, ignoring the result of the Greek referendum of 5 July and accepting the consequent fury and further declining public assent for the Project. In the course of research for a project on European integration undertaken following the 2005 French and Dutch referenda, an eminent Belgian interviewee happily confirmed Monnet’s view that federalists never waste a good crisis, and indeed welcome them. He employed the charming, informative (and, to any horseman, dangerously inaccurate) analogy that “you have to frighten a horse to get it to jump a big hedge.”16 A frightened horse is an unreliable horse that will one day buck you off. This all looks like a pyrrhic victory. In Leviathan Thomas Hobbes lists “the insatiable appetite, or bulimia, of enlarging Dominion” as one of the “diseases of a Commonwealth”. The EU is still only a regulatory machine and patently not become a state of mind for Europeans. (By the way, this is why it is no more likely to exceed a human life-span from foundation to death than did the USSR). The legal philosopher Philip Allott mordantly observes that “bulimia plus bureaucracy is a reliable recipe for the decline and fall of empires.”17 The July Crisis of 2015 has gutted the currency experiment; and the debauching of Greek sovereignty by German paymasters, trying to treat a state like a busted factory, is indeed a dirty fall for the whole Project. It has had two further consequences. The humiliation of Syriza was clearly intended to be a deterrent; but it may have produced the opposite effect, alienating the Project’s natural supporters on the Left. In Britain, Jeremy Corbyn has hinted as much. Worse, the attempted criminalisation of the former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis for having dared to draw up secret contingency plans for a return to the drachma has inflamed the confrontation.18 The British electorate will not have failed to notice all this. Allott presciently remarked that the crisis facing the EU is neither technical nor bureaucratic: it is fundamentally one of social philosophy. Matters of personal and political culture have been the least common framing of the question of the EU’s costs and benefits. Yet they are of the very essence when judging the national interest. In the British case the Magna Carta concerns are preeminent: for the sovereignty of the monarch in Parliament, the distinctiveness of the Common Law, the rights of property, of habeas corpus and of a British citizen’s freedom under the law, which was Britain’s gift to the world.19 15 Juncker (Commission), Tusk (Council), Dijsselbloem (Eurogroup), Draghi (ECB), Schulz (EuroParliament), European Commission, (2015) 16 Prins & Möhring (2008), Preamble and passim. 17 Ch 29 “Of those things that weaken, or tend to the Dissolution of a Commonwealth”, Hobbes (1651, 1985 edition), p.375; Allott (2002), p. 175 and, on the ‘unimagined community’ of the EU, pp 229-262. 18 Evans-Pritchard (2015) 19 A story freshly and readably retold from beginning to end in Hannan (2013). The initial trigger to a vigorous reexamination of why and how British society diverged from that of the continent was Macfarlane (1978). Scruton (2000) elaborates clearly how the essential enduring features grow from these foundations to become, in Edmund Burke’s famous image, the great oak tree which shelters the ‘little platoons’ of English society which are the first principle of public affection, leading to patriotism. The shallower eighteenth century overlay described by Colley (1992) and what is happening to it, must not be confused with these foundations. Beyond the Ghosts 12 The flaw in Europeanism Rebellion against a fake and forced European identity has taken hold across the nations of continental Europe over recent decades. It is intensely threatening to the world-view and sense of entitlement of the EU elite because it strikes at the heart of the foundation myth of Europeanism. It deepens the gulf between rulers and subjects who now wish to be citizens and not just atoms in ‘civil society.’ Larry Siedentop famously applied Alexis de Tocqueville’s four tests of democratic legitimation formed from his observations of America, to Europe. De Tocqueville’s mid nineteenth century tests had much in common with Edmund Burke’s late eighteenth century view of how living society was constituted. The tests were: the habit of local self government; a common language; an open political culture dominated by lawyers; some shared moral beliefs. Siedentop argued that Europe failed the tests principally because there is no culture of consent nor the ingredients to make one (which makes this a basic reason why Britain should maintain sea-room from the continental lee shore). 20 But what are the causes of this longstanding deficit in Europe? They are neither shallow nor trivial and we must look well before the double disasters of the two World Wars that seared the minds of Monnet and his friends to understand them. France has struggled to the present via fifteen further constitutions from its ‘stock-jobbing constitution’ of 1789 (…”the display of inconsiderate and presumptuous because unresisted and irresistible authority” in Burke’s contemporary description). Germany and Italy were established only a bit more than a century ago and state identities (let alone democracies) across southern and eastern Europe are more fragile and newer still. In such company, Britain is unusual as an old country that once successfully ran the world’s largest empire and three times saved Europe from itself since 1815. However there is a more fundamental difference than either success or age between Britain and all those large European countries created ‘from above.’ It is a difference in culture. Edmund Burke pointed towards it in 1790 as he reflected on the revolution in France the previous year. He observed that British liberties are asserted as an entailed inheritance from our forefathers, rather than grabbed as abstract rights that adhere to and inhabit the individual as an atom interacting with other lonely atoms to create ‘civil society’. Burke’s explanation of the organic roots of society therefore stands at a polar opposite. British rights rise up from below; they are not granted from above. Starting as Aristotle did, with the family, he locates “…the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affection…” in the “little platoons …the first link in the series by which we proceed to a love of our country and to mankind.” In a second dimension as well, this origin and this ‘bottom-up’ dynamic make the British approach to social contract entirely different from Rousseau’s, for it reaches across the generations: “Society is indeed a contract… it is a partnership in all science; a partnership in all art; a partnership in all virtue and in every perfection. As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many generations, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.”21 20 Siedentop (2000). 21 Burke (1790, 1968 edition), quotations at, successively, p. 142; p.127; p. 119; p.135; pp 194-5 13 Writing in his magisterial history of England, Robert Tombs mentions an insightful consequence arising from this British framing of rights: “it is hard to think of any major improvement since Magna Carta brought about in England by violence.” Lacking this special chemistry which gives continuity and rootedness to British citizenship, continental historical experience, utterly alien to Britain, has, in contrast and in repeated ferment, brewed up ‘vanguard myths’ that morally justify despotic rule in the imposition of identities on people and that validate a determinist view of history. It is this same concoction that set Burke’s nostrils aquiver in 1790: “The worst of these politics of revolution is this; they temper and harden the breast….so taken up with their theories about the rights of man, that they have totally forgot his nature. “ [emphasis added] Human rights have been turned into a quasi-religious dogma by today’s intellectual descendants of the French revolutionaries. But the very concept is slippery and hard to pin down. To what extent is it actually, enforceably, normative and to what extent simply aspirational rhetoric? To what extent can or should human rights be more than an emergency back-stop? ‘Human rights’ deserve inverted commas because they are not self-evident truths beyond discussion. In the real world of negotiating humane and tolerant society, how can ‘claim rights’ be separated in practice from the performance of obligations, to earn and to deserve them? Human rights in the abstract are not a valid expropriating trump card in the political game where the prize is impregnable control of cultural norms and hence of both power and money, even when played as it was in 1789 and often is today on the back of loosely worded and prescriptive portfolio legislation. And when it is played, the ‘human rights’ card can be dangerous and can produce entirely unexpected and undesirable consequences. This dark side of human rights is especially seen when attempts to enforce claim rights (rights to goods and services) as normative, simply serve to dishearten or prevent performance of services by obligation-bearers so that everyone is worse off. Dazzled admirers of abstract liberty rights just do not see this dark side. Baroness O’Neill observes incisively that this darkness was preordained at the very moment of creation of the concept of ‘human rights.’ It was a result of a muddled allocation of obligations to rights in the Universal Declaration of 1948. It is a defect which has infected all the EU derivatives. 22 It is particularly important to understand this quite clearly today both because the EU uses ‘human rights’ as an all-purpose instrument to increase and seal the acquis communautaire and because Great Britain is at last preparing to regain space for its conceptually different method of protecting rights, which is broadly Burke’s method. This will require repeal of the Human Rights Act 1998, and most especially the all-embracing Article 3(1), which politicises the Judiciary for the first time in modern history and which contaminates assessment of all legislation without exception.23 ‘Human rights’ have been hijacked by special interest groups (and with less noble motive by eagerly rent-seeking lawyers in specialist chambers) and they need to be rescued from the human rights movement. This type of top down Europeanism, framed on a skeleton of abstract rights and propelled by ‘vanguard myths,’ has no interest in a culture of consent nor any serious interest in who people are. Why? Because it simply is not necessary. A self-justified act of ruling from above imparts 22 Tombs (2014) p. 886; R.Tombs, “Europeanism and its historical myths,” in (ed) Abulafia, (2015), p.26; Burke (1790) p.156; O’Neill (2005) passim. For the human story of the drafting of the UDHR, see Glendon (2001) and especially how René Cassin’s “Portico” analogy helped to inscribe structural flaws, pp 173-91 23 “So far as it is possible to do so, primary legislation and subordinate legislation must be read and given effect in a way which is compatible with the Convention rights.” Human Rights Act 1998, “Interpretation of Legislation” Art 3(1). You cannot be more catch-all than that: the escape hatch is very narrow. Beyond the Ghosts 14 information and delivers instructions. It is not a new tendency. In 1714 Bernard Mandeville introduced his ever topical explanation of human nature by observing that “One of the greatest Reasons why so few People understand themselves, is, that most Writers are always teaching Men what they should be, and hardly ever trouble their heads with telling them who they really are.”24 It has been a feature of earlier ‘European ideas’ too, before this one, notably the Fascist ‘Triumph of the Will’ of the 1930s; and of course belief in the ‘false consciousness’ of the masses makes it the basic conceit of all Marxists, including today’s resurgent pan-European hard Left.25 Sleight of hand has also been a consistent common feature of Europeanism as Bismarck remarked in 1871: “I have always found the word ‘Europe’ on the lips of those who wanted something from other powers which they dared not demand in their own name” and as General de Gaulle affirmed in terms in 1962: Europe is the way for France to become what she has ceased to be since Waterloo. What the ghosts did Ghosts haunt each side. Shocked by President Eisenhower’s brutal undermining of FrancoBritish military success in the 1956 Suez operation, forcing ignominious withdrawal, the British ruling class lives in a generalised fear and presumption of decline from former power that still haunts Whitehall. Sir Anthony Nutting observed at the time that Suez was “no end of a lesson”; and the lesson was that if the Americans couldn’t be trusted, and with them that whole implicit confidence in the anglosphere as Britain’s multiplier of influence, then better try to join the club next door. The Commonwealth was treated atrociously. It is a tribute to the strength of the ties that bind the anglosphere that as a consequence it did not fall apart in the 1950s. That the Commonwealth is so vibrant, popular and expanding today is one of Her Majesty the Queen’s greatest gifts to her people. More far-seeing than her ministers, her skilful, quiet and steadfast commitment over forty years has preserved a possibility of renewal such that “the UK could use [the Commonwealth] as a power multiplier, like the EU but without the assimilation costs.” Given how Commonwealth economies are thriving in contrast to the troubled or waning economies of the Eurozone, Britain’s relationship with the Commonwealth requires a major rethink leading to mutually beneficial amplification and realignment.26 The Continental ghost already examined is fear of recurrent war. It has dangerously perverse effects. It skews history by suggesting that it was the Project of European union that somehow has prevented European war since 1945 whereas straightforwardly that was the work of the Marshall Plan followed by the American-led NATO alliance. Furthermore it blinds believers to the dangers of ramming ‘vanguard’ Europeanism onto people, which, as in the Greek July Crisis, shreds fragile democracies. Chillingly, it also summonses dark shadows of both Left and Right extremism as Donald Tusk, President of the Council, correctly identifies: “It is always the same 24 Mandeville (1714) 1970 edition, p.77 25 The ‘European idea’, Leach (2004) pp 92-96 26 (eds) Elliott & Moynihan (2015), p.271 and Hewish (2014) passim, but esp pp 50-73. He handily enumerates the ties that bind the English-speaking peoples. 15 game before the biggest tragedies in our European history”.27 The Project was supposed to banish them forever. Instead, it does the opposite. Therefore we must go beyond the ghosts. We cannot do this unless we understand who they were, what they did to get us where we now are and how, if they are denied or ignored, they can control us still. David Cameron was correct to observe that “there is not, in my view, a single European demos’ in his Bloomberg speech in January 2013. In fact, Jean Monnet’s expectation that a new European identity would, generation by generation, through force of historical inevitability, permeate people like dye into wool, has been inverted. An admittedly crude measure comes from Spinelli’s European Parliament. The results of its elections show how for years the people across the continent have been drifting away. Participation levels have fallen at every election since its inception but the proportions of MEPs elected has changed markedly. At the last election, more ‘eurosceptic’ MEPs were returned than ever before. To the July Crisis: the hollowing out of European politics Determinist Europeanism, the ‘Monnet Method’ and fear of their ghosts mean that the EU political elite neither value, respect or fear the concerns of the electorates. A decade ago rulers and ruled took different pathways that have now circled and collided in the Greek July Crisis.28 Divergence began in 2005 with the French and Dutch referenda rejections of Giscard d’Estaing’s self-amending European Constitution, which, coming after the Euro, was the next planned milestone on the road to open federal union.29 In the Dutch case, rejection was by two thirds of two thirds of one of the most mature democracies on the continent and the only well-functioning one to have signed the Treaty of Rome.30 Yet the verdicts were evaded recklessly by repackaging the constitution as the ‘Lisbon Treaty.’31 Then came the Third No – the Irish referendum on the ‘Lisbon Treaty’ on 12th June 2008. The Irish gave the ‘wrong’ answer, so were obliged to correct their mistaken verdict in another referendum, as also happened to the Danes. These results already suggested that two internally consistent but mutually irreconcilable visions of Europe were in collision.32 27 cit Evans-Pritchard (2015) 28 The origins and now realised potentialities of the Euro were discussed at that time in Prins, (2005) and placed in context in Leach (2004) ‘EMU’ pp 70-75 29 The definitive ‘insider’ account of how Giscard and his aide Sir John (now Lord) Kerr (formerly Permanent Secretary of the FCO) wrote this extraordinary document and attempted to foist it first on the Praesidium and then on electors is by Stuart (2003). 30 The Dutch association of inherent political freedom with skill in reclaiming land from water goes back to the thirteenth century, Pye (2014) p.172 31 The definitive documentation of this deliberate deceit is Open Europe (2007). Of salutary shock are Annex 1 which lists areas where the national veto was lost and Annex 3 which provides a concordance matching the Constitution with the Treaty clause by clause. 32 Inspired by the example of The Federalist Papers of 1787 written by ‘Publius’ (James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay) as a contribution to the same debate which this essay also seeks to enter and in order, as ‘Publius’ did in the American case, to force clarity and thereby assist informed discussion, Ms Möhring and I have placed the two contending views systematically in the mouths of two imaginary friends, ‘Publia’ and ‘Lydia’, using quotations from an extensive series of interviews that she conducted across the continent. Prins & Möhring (2008) Beyond the Ghosts 16 More recently and in quick succession, opinion polls and political classes did not see three results coming: the Scottish majority to remain in the United Kingdom in the 2014 referendum; the British General Election result of May 2015 which returned a majority Conservative government and the 60% Greek ‘No’ on 5th July 2015, which was instantly ignored. In all these three cases the likelihood is that for different reasons including fear of the SNP in Scotland, electors simply lied about their intentions to the pollsters. If so, this further etches the widening gulf between rulers and ruled and begs the question why. The recent emergence of anti-austerity parties backed by younger, well-educated voters in Greece or Spain (Syriza and Podemos) may be especially evident in the southern European countries that are victims of social mayhem created by the Euro; but it is in fact an aspect of a general hollowing of European politics that has been most fully documented by Peter Mair in Ruling the Void. Mair’s data documents a trend for voters to cease to vote, or if they do vote, to be increasingly likely to switch preferences from one election to the next, that can be found across all European democracies since 1990. This, he argues, is because of growing public recognition of depoliticised, technocratic forms of decision-making. The response has been a politics of protest (fertile and familiar ground for the hard Left) via judicial or quasi-judicial methods, or by media and especially modern ‘social media’ campaigns, or in the streets, rather than by appeal at the redundant ballot box. Insofar as voting is popular, referenda are favoured, shortcircuiting the untrusted political class. Mair concludes that the modern state is viewed increasingly as regulatory and decreasingly as participatory. His finding, which supports this, is that since 1980, across all the European democracies, established political party membership has declined on average by 50% (with range from minus 66 to minus 27).33 But what matters for present purposes is that Mair emphasises the role played by the character of the EU in the hollowing out of European democracy. The EU has constructed “…a protected sphere in which policy-making can evade the constraints imposed by representative government.”34 He too believes that this has aggravated the general trend, because the EU elite’s contempt for the electorate is reciprocated. Therefore it is not surprising to see a two pronged countervailing response. On the one hand there is the current rapid growth of ‘anti-party’ politics in most EU countries, especially ‘core’ countries, and on the other of fierce, romantic nationalist parties in Scotland, Catalonia, Northern Italy and elsewhere. After its crushing defeat in May 2015, the unpredicted enthusiasm for Jeremy Corbyn in the British Labour party and most especially among its newly enfranchised ‘clicktivist’ cuckoos, shows that young British voters, like young Greeks or Spaniards, are not deterred by the trampling of Syriza. But it may also mean that the hard Left is reading and riding these trends carefully and that the potentials for a revival of anarcho-syndicalist street politics in Europe are greater than democrats credit. One must always remember that the hard Left does not wish to win elections even if it could, only to discredit the democratic process. 33 Mair (2013), Table 4, ‘Party membership change in established democracies 1980-2009’ p.41 34 Mair (2013), p.99. 17 On this evidence, as well as evidence of public fear and anxiety about the terrorism of the Da’esh and the failure to control the trans-Mediterranean migration crisis, it would be wise for the political and academic elites to acknowledge that deeply embedded and deeply felt but usually inchoate issues of personal and national culture are likely to be decisive in the forthcoming British referendum. Gulliver and the balance of competences In the preferred metric of federalists, it is noteworthy that British self-interest increasingly favours resumption of sovereign independence in global markets. That is not simply because in quality, in match to British strengths or in size relative to growing markets, the troubled EU market diminishes while the Commonwealth, the anglosphere and emerging markets increase, but because of the many regulatory cords with which the EU ties the British Gulliver down. Because of Qualified Majority Voting (QMV) and the uni-directional engrenage of the acquis communautaire, they make a negotiated release acceptable to the British electorate most unlikely. Therefore, turning to the practical mechanics of exerting world-wide diplomatic and especially ‘soft power’ influence, we may see that should we remain under the ever expanding powers of the EU ‘External Action Service’, particularly if (when) planned extensions of QMV occur, the balance of cost and benefit also tilts sharply against British participation in this part of a project of Union, for the same ‘Gulliver’ reasons. Beyond the Ghosts 18 In July 2013 the FCO published a report on the “Balance of Competences” between Britain and the EU. A Venn diagram reminds us of the range of special British advantages compared to any other EU member, showing our many institutional memberships, especially the Commonwealth. Alone in Europe, Britain holds a royal flush. 35 The report is revealingly conflicted. The FCO authors gamely make as good a fist as they can of the standard Whitehall case. In a different context than that of the EU, it sounds reasonable: that by being inside we can shape and lead, that we gain “increased impact from acting in concert with 27 other countries” and that outside we would be diminished. However, evidence does not support this. Both the dismal record of Baroness Ashton, Mr Brown’s appointee as first ‘High Representative’, and the evidence within their report of overall dismal performance of the EU as a foreign policy actor, overwhelmingly run against. Yet momentum increases. They admit frankly that the weight of money, posts and driving ambition to expand the influence of the EEAS cannot but crowd out the under-funded and shrinking FCO. Much more deadly to the case for staying inside is the FCO’s own assessment of how the ratchet works. It deserves full quotation: … when EU law gives the institutions power to act internally in order to attain EU objectives, the EU implicitly also has the power to enter into international obligations ‘necessary’ for the attainment of that objective, even when there is no express provision allowing it to do so (emphases added). In construing ‘necessary’ in the case law, the ECJ only asks whether the external action in question pursues an objective of the Treaties, rather than whether external action is indispensible to the attainment of that objective. 36 The most thorough independent analysis of the ‘Balance of Competences’ report has been published by Business for Britain in Change or Go, to which the reader is referred. It also quotes the passage above in arguing that ‘representation creep’ is insidious and quotes the FCO authors in further support: “The EU has over many years sought, in one way or another, to increase its role and present itself as a ‘single voice’…put simply, the UK sees a risk that representation comes to equate to competence.” 37 And Whitehall actually knows our strengths. The authors of Change or Go realised that under pressure from a different crisis, one year after ‘Balance of Competences’, Whitehall made a much more generous assessment of British power and potential. Therefore they cite the analysis produced when it seemed that the Union was about to be lost. The Scotland Analysis noted how little Britain requires the duplicating services of the EEAS “to win new business, attract inward investment and champion the reputation of the UK economy.” It enumerated the agents which increase British influence that are located in our network of Embassies and High Commissions and they rightly presented Britain as a ‘soft power superpower’.38 35 36 37 38 H.M. Government (2013), Para 1.4, Fig 1, pp 13-14 H.M. Government (2013) p.21 Chapter 8, “Foreign Policy,” (eds) Elliott & Moynihan (2015) pp 254-286. “Representation creep’ is discussed at pp 278-9 H.M. Government (2014), pp 41-9, cit, (eds) Elliott & Moynihan (2015) pp 269-70 19 Change or Go also highlights two other powerful but second order technical reasons why Britain’s national interest to engage its European neighbours effectively in alliance is blocked by our subordination to the Lisbon Treaty. The first is that as a function of being crowded out in the international institutions, the EU constitutes “a direct and growing threat to British influence” so that “…in these terms, the EU is not a force multiplier for British diplomacy but an inhibitor.” Like a mosquito, it also carries a hidden further risk. The more that the EEAS enters the career-stream for high-flying British diplomats on secondment, the more personnel ‘go native’ and the fewer are left for national duties.39 The second is the danger to a vital national interest entangled in the EU’s current attempt to switch from energy policies designed to support ‘climate action’ to policies designed to protect the more traditional and comprehensible goal of energy security. Energy is an ‘EU competence’ and as Change or Go writes correctly, “energy security is one of the weakest links in EU joint action”. The story is complex, intriguing and little known. It is told elsewhere in full, but in brief, the arrival of the Juncker Commission in 2014 led to some brutal internal powerpolitics in Brussels.40 While preserving an appearance of continuity of commitment, in fact during 2014-15 ‘climate action’ rapidly dropped in importance as the resurgence of Putin’s Russia in the context of the endless Eurozone crisis prompted a strong initiative to proof the EU gas supply system against Russian energy blackmail (which of course is what Helmut Schmidt’s policy of pipeline entanglement with Russia was supposed to prevent). As with fisheries, Britain could find itself under pressure to provide access to national strategic reserves as well as at competitive disadvantage from the Civil Service’s obedient gold-plated application of environmental energy measures that other less law-abiding countries ignore in this volatile context. Therefore the Energy Secretary’s ‘reset’ speech of 18 November 2015 at the Institute of Civil Engineers had special strategic importance. Following broadly the same revision of priorities that had been seen in EU energy and climate policies, Amber Rudd announced measures to remove some of the most distorting subsidies for non-dispatchable sources of generation which also impose severe additional system management costs on consumers and to prioritise Britain’s use of a ‘gas bridge’ as quickly as possible to attain more secure and cleaner energy generation in the future. It was not only a beginning in trying to restore balance to what over the past decade has become an energy market heavily deformed as a consequence of crude gesture politics, it also set a course for the country to regain sovereign control of energy - the essential animator of the economy - from the EU. Plainly the repatriation of this ‘competence’ from Brussels must be a national security priority in any further negotiations before the British referendum is held. Failure to achieve it will be among the prime indicators to vote to leave.41 The EU’s attempt to reverse priorities is made more tense by the progressive poisoning of the German economy by very high electricity costs and loss of national reserve capacity resulting from the energiewende policy to prioritise high cost, subsidy dependent and nondispatchable generators.42 Mr Obama has not helped here either. His swan-song rhetoric on 39 (eds) Elliott & Moynihan (2015), p.256, p.280, p.286 40 (eds) Elliott & Moynihan (2015), p.273. The full story of the EU’s on-going attempt to switch from a ‘climate action’ to an energy security priority is given in Prins (2015) 41 Rt Hon Amber Rudd MP, 18 November 2015. To understand the full significance of this very important change of policy, see also Prins et al, (2013) 42 Why the energiewende poisons the German economy is explained from first principles in Constable (2014) Beyond the Ghosts 20 ‘climate action’ via Executive powers in the USA will in any event most likely be snarled up in the courts and Congress. Furthermore his policy is perverse because US shale gas has already materially reduced US carbon intensity and particulate pollution although Mr Obama’s plan, if effected, will hobble it and with it the current US economic vitality that innovative frackers have helped to underpin. Successful negotiation requires informed statesmanship These technical arguments from diplomacy for withdrawal from the power of the Lisbon Treaty are weighty in their own terms; but together they are more than the sum of the parts as Change or Go crisply summarised: “ The problem is circular from a UK perspective for as long as it remains joined to the CFSP. The European diplomatic cadre is a hindrance if it remains ineffective and dangerous if it becomes competent. Withdrawal from the CFSP removes both threats.”43 Added to the deeper reasons that this essay has proposed, the removal of Britain from the spider’s web of the acquis communautaire, which snares everything, is the prerequisite for the reconstruction of mature and healthy relations with our neighbours and renovation of alliances of interests. The spider’s web traps axiomatic issues of national identity, interests and security with peculiar tenacity. If this change cannot be achieved by negotiation and revision of the EU Treaties – and there is no historical evidence whatsoever to believe that an adequate renegotiation can be achieved, but rather the evidence of the Greek July Crisis of 2015 that is before our eyes - then in the forthcoming referendum the course of action for an electorate that speaks for Britain is quite clear. We should escape and leave. Our world-wide interests steadily outweigh our continental ones. In pursuing both, our subordination to the instruments of the Lisbon Treaty does more harm than good. As Prime Minister Salisbury would remind us, only when we are no longer under their power can we once more work safely and whole-heartedly with our European allies. Particularly during 2015, we could see with our own eyes that the wheels are finally coming off this latest project for European union; so it is primarily important for the sake of our national interest to be liberated from that power. But it is also important for our friends. Once more we may need to be found in our place to help when actual danger once more menaces the System of Europe. The EU is reaching the natural life-span of any political apparatus without a ‘demos’; and as its promoters rage against the dying of the light, the project of European union is becoming that danger. Ironically and tragically, given the fears and idealism of its founders, the EU steadily and increasingly now menaces the peace, wealth and happiness of Europeans. © G.Prins 2015 43 (eds) Elliott & Moynihan (2015) p.265 21 References (ed) Abulafia, D, ‘European Demos’ A Historical Myth? Historians for Britain, London, 2015 Allott, P, The Health of Nations: Society and Law beyond the State, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002 Bew, J, Castlereagh: Enlightenment, War and Tyranny, Quercus, London, 2011 Burke, E, Reflections on the Revolution in France, 1790, Penguin edition, Harmondsworth, 1968 Carls, A-C & Naughton, “Functionalism and federalism in the European Union,” Public Justice Report, (2), 2002 Churchill, W.S., The Second World War, Vol VI, Triumph and Tragedy, Cassell & Co, London, 1954 Clark, C, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe went to War in 1914, Penguin, London, 2012 (eds) Elliott, M & Moynihan, J, Change or Go, Business for Britain, London, July 2015 Colley, L, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707- 1837, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1992 Constable, J. “Thermo-Economics: Energy, Entropy and Wealth,” B&O, Economic Research Council, 44 (2) Summer 2014, pp 3-14 Cooper, R, The Breaking of Nations: Order and Chaos in the 21st Century, Atlantic, London, 2003 European Commission, Completing Europe’s Economic & Monetary Union, June 2015, http://ec.europa. eu/priorities/economic-monetary-union/docs/5-presidents-report_en.pdf Evans-Pritchard, A, “Monetary chaos has created the perfect recipe for European civil war,” The Daily Telegraph, 30 July 2015, p.26 Glendon, M.A, A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Random House, New York, 2001 Hannan, D, How We Invented Freedom and Why it Matters, Head of Zeus, London, 2013 Hansard, “Europe: renegotiation – Statement to the House, David Lidlington MP, Minister for Europe, 10 November 2015” Gisela Stuart MP at Col 230; Bernard Jenkin MP at Col 236 Hewish, T, “Old Friends, New Deals: The Route to the UK’s Global Prosperity through International Networks,” IEA Brexit Prize finallist, IEA, London, 2014 HM Government, Review of the Balance of Competences between the United Kingdom and the European Union Foreign Policy, HMSO, London, July 2013 HM Government, “Scotland Analysis: EU and International Issues,” HMSO, London, 2014 Hobbes, T, Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth eccesiastiall and Civill, London, 1651, Penguin Classics edition, London, 1985 Kissinger, H, A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace 1812-22, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 1957 Kissinger, H, World Order, Penguin, New York, 2014 Leach, R, Europe: A Concise Encyclopedia of the European Union, Profile, London, 4th Edition, 2004 Beyond the Ghosts 22 Macfarlane, A, The Origins of English Individualism: The Family, Property and Social Transition, Blackwell, Oxford, 1978 Mair, P. Ruling the Void: the Hollowing of Western Democracy, Verso, London 2013 Mandeville, B, The Fable of the Bees, (1714), Penguin Classics edition, Harmondsworth, 1970 (eds) Möhring J. & Prins, G, Sail on O Ship of State, Notting Hill Editions, London, 2013 O’Neill, O, “The dark side of human rights,” International Affairs, 81,2 (2005) pp 427-39 Open Europe, A Guide to the Constitutional Treaty, Open Europe, London, August 2007 Petraitis, D, Reorganisation of the Russian Armed Forces, 2005-15, Series 4, Working Paper 43, Dept of Strategic & Defence Studies, National Defence University, Tampere, Finland, 2012 Petraitis, D, “Russian military reform: success and new forces” Unclassified Lecture at the Baltic Defence College, Tartu, Estonia, 3 November 2015 Prins, G, “The end of the European Union”, Open Democracy, 25 May 2005 https://www.opendemocracy.net/democracy-europe_constitution/EUconstitution_2542.jsp Prins, G. & Möhring, J, Another Europe? After the Third No, Lilliput Press, Dublin, 2008 Prins, G et al, The Vital Spark: Innovating Clean and Affordable Energy for All, The Third Hartwell Paper, London School of Economics, 2013 Prins, G. “Changing priorities on ‘climate action’ and energy policy in Europe as they have emerged during 2014: a strategic assessment” Institute of Energy Economics of Japan, April 2015, http:// eneken.ieej.or.jp/data/6034.pdf Pye, M, The Edge of the World: How the North Sea made us who we are, Penguin, London, 2014 Rudd, A, “A new direction for UK energy policy” Institute of Civil Engineers, London, 18 November 2015, https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/amber-rudds-speech-on-a-new-direction-for-ukenergy-policy Rummel, R,J, Death by Government, Transaction, Brunswick, NY, 1994 Salter, A, The United States of Europe, George Allen & Unwin, London 1931 Scruton, R, England: An Elegy, Chatto & Windus, London, 2000 Siedentop, L, Democracy in Europe, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 2000 Stuart, G. MP, The Making of the European Constitution, Fabian Society, London, 2003. Tombs, R, The English and their History, Allan Lane, London, 2014 Ward, A.W & Gooch, G.P, Cambridge History of British Foreign Policy, Vol II (1815-1866), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1923 23 About the Author Gwythian Prins MA, PhD (Cantab) FRHistS is of Anglo-Dutch parentage and completed the classe de philo in Paris in 1968. He is Emeritus Research Professor at the London School of Economics, Visiting Research Professor and Visiting Professor of War Studies at the Humanities Research Institute, University of Buckingham. He was previously Alliance Research Professor jointly at Columbia University in New York and the LSE but for most of his career was a Fellow and the Director of Studies in History at Emmanuel College and University Lecturer in Politics, University of Cambridge. In his public service career he has served in the Secretary General of NATO’s Special Adviser’s office at the end of the Cold War and also as Senior Visiting Fellow in DERA, the UK Ministry of Defence’s former research establishment, where he scrutinised defence projects and led research on strategic assessment methodology. Since 2011 he has served on the Strategy Advisory Panel of the Chief of the Defence Staff and is also a serving member of the Royal Marines Advisory Group. His publications range from an awardwinning history of western Zambia to books and essays on medical anthropology, energy and environmental policy (including a work on the anthropology of air-conditioning which established a sub-discipline in energy studies), on principles of strategy, the ethics of war and on military history. His next book takes the long view to reflect on the reasons for the epidemic of certainty and the demonisation of doubt that have become such prominent features of modern times. Beyond the Ghosts 24 Business for Britain exists to give a voice to the large, but often silent, majority among Britain’s business community who want to see fundamental changes made to the terms of our EU membership. We are independent and non-partisan, involving people from all parties and none. As a campaign, we aim to reflect the views of our business signatories, and the campaign is represented in the media and at events by people with real business experience. By pushing these voices into the mainstream – through quality research, eye-catching campaigns, rapid rebuttals and set-piece events such as lectures and debates – Business for Britain ensures that the British people understand that many UK business people want a better deal from Brussels and are not scared to fight to achieve that change. Please note that all signatories have signed up to Business for Britain in a personal capacity. Board Neville Baxter, RH Development (Director) Harriet Bridgeman CBE, Bridgeman Images (Founder) Dr Peter Cruddas, CMC Markets (Chief Executive) Matthew Elliott, (Chief Executive), TaxPayers’ Alliance (Founder) Alan Halsall, (Co-Chairman), Silver Cross (Former Chairman) Robert Hiscox, Hiscox Ltd (Honorary President) Daniel Hodson, (Honorary Treasurer), LIFFE (Former CEO) John Hoerner, Tesco Central European Clothing (Former CEO) Brian Kingham, Reliance Security Group (Chairman) John Mills, (Co-Chairman), JML (Chairman and Founder) Jon Moynihan OBE, PA Consulting (Former Executive Chairman) Business For Britain is a Company Limited by Guarantee in England No. 8411261 Beyond the Ghosts 26 Westminster Tower, 3 Albert Embankment, Lambeth, SE1 7SP 0207 340 6070 (office hours) info@businessforbritain.org www.facebook.com/ForBritain @forbritain www.businessforbritain.org Designed by Wordzworth Limited. Printed by Solopress. HISTORIANS ----for BRITAIN "Anyone thinking about whether we should continue to be part of the present-day Union needs to reflect on Gwythian Prins's brilliant insights." - Professor David Abulafia, Cambridge University "Gwythian Prins has produced an elegant and forceful essay with a scholarly historical context" - Professor, the Lord Bew, Queen's University