Building the Board at the Small Enterprise Foundation

advertisement

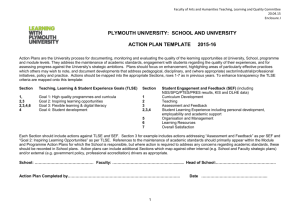

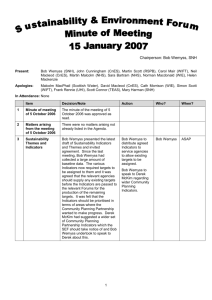

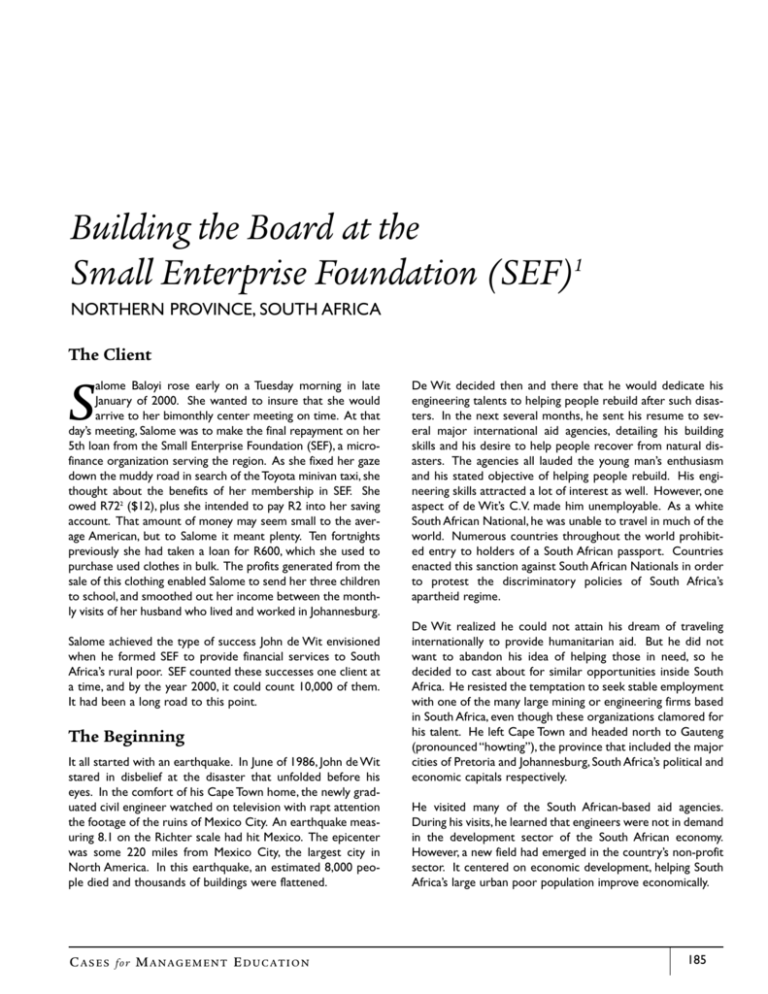

Building the Board at the Small Enterprise Foundation (SEF)1 NORTHERN PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA The Client alome Baloyi rose early on a Tuesday morning in late January of 2000. She wanted to insure that she would arrive to her bimonthly center meeting on time. At that day’s meeting, Salome was to make the final repayment on her 5th loan from the Small Enterprise Foundation (SEF), a microfinance organization serving the region. As she fixed her gaze down the muddy road in search of the Toyota minivan taxi, she thought about the benefits of her membership in SEF. She owed R722 ($12), plus she intended to pay R2 into her saving account. That amount of money may seem small to the average American, but to Salome it meant plenty. Ten fortnights previously she had taken a loan for R600, which she used to purchase used clothes in bulk. The profits generated from the sale of this clothing enabled Salome to send her three children to school, and smoothed out her income between the monthly visits of her husband who lived and worked in Johannesburg. S Salome achieved the type of success John de Wit envisioned when he formed SEF to provide financial services to South Africa’s rural poor. SEF counted these successes one client at a time, and by the year 2000, it could count 10,000 of them. It had been a long road to this point. The Beginning It all started with an earthquake. In June of 1986, John de Wit stared in disbelief at the disaster that unfolded before his eyes. In the comfort of his Cape Town home, the newly graduated civil engineer watched on television with rapt attention the footage of the ruins of Mexico City. An earthquake measuring 8.1 on the Richter scale had hit Mexico. The epicenter was some 220 miles from Mexico City, the largest city in North America. In this earthquake, an estimated 8,000 people died and thousands of buildings were flattened. C A S E S for M A N A G E M E N T E D U C A T I O N De Wit decided then and there that he would dedicate his engineering talents to helping people rebuild after such disasters. In the next several months, he sent his resume to several major international aid agencies, detailing his building skills and his desire to help people recover from natural disasters. The agencies all lauded the young man’s enthusiasm and his stated objective of helping people rebuild. His engineering skills attracted a lot of interest as well. However, one aspect of de Wit’s C.V. made him unemployable. As a white South African National, he was unable to travel in much of the world. Numerous countries throughout the world prohibited entry to holders of a South African passport. Countries enacted this sanction against South African Nationals in order to protest the discriminatory policies of South Africa’s apartheid regime. De Wit realized he could not attain his dream of traveling internationally to provide humanitarian aid. But he did not want to abandon his idea of helping those in need, so he decided to cast about for similar opportunities inside South Africa. He resisted the temptation to seek stable employment with one of the many large mining or engineering firms based in South Africa, even though these organizations clamored for his talent. He left Cape Town and headed north to Gauteng (pronounced “howting”), the province that included the major cities of Pretoria and Johannesburg, South Africa’s political and economic capitals respectively. He visited many of the South African-based aid agencies. During his visits, he learned that engineers were not in demand in the development sector of the South African economy. However, a new field had emerged in the country’s non-profit sector. It centered on economic development, helping South Africa’s large urban poor population improve economically. 185 CASE STUDIES Exhibit 2. Provincial Map of South Africa Exhibit 1. Map of South Africa De Wit pursued these opportunities and landed a job with the Get Ahead Foundation (GAF) funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). GAF provided small business loans to individual entrepreneurs who operated existing businesses. The average loan of this program was $10,000, and the repayment rate hovered around 30%. Prior to adopting the revolving loan fund methodology, GAF gave outright grants to this same target market of small business owners. Now lending money, it was delighted to extend its available capital by 30% by re-issuing funds received as repayment for loans. This improvement over the grantmaking program meant that they could reach more entrepreneurs each year. learn more about the Grameen Bank. Since South Africa remained isolated from the outside world because of antiapartheid sanctions, he found it difficult to get material. In the end, he managed to get some publications from USAID on peer lending and the Grameen Bank. He contrasted what he learned in this reading with his work at GAF. He questioned the performance of his organization. Were they helping the people who needed the most help? Why did his organization achieve only a 70% repayment rate, while the Grameen bank lent to a much poorer clientele and did much better? In his continuing work with the pilot program, he was disappointed that its terms of operational performance peaked at a maximum 70% repayment rate. He decided to leave the organization. He began working as a consultant, bringing the idea of peer lending to other economic development organizations in South Africa. Most of A USAID consultant visited the organization to offer advice on the program design. He had been to Bangladesh and seen the Grameen Bank at work. The Grameen Bank achieved repayment rates close to 99%, largely using a peer-lending methodology. The crux of this method involved organizing individual entrepreneurs into groups of five, and the five guaranteed each other’s loans. It also lent smaller amounts of money than GAF and required a clean repayment record for entrepreneurs seeking additional loans. The consultant advised GAF to implement this method in their region of South Africa. He advocated a program that reduced the loan size to $1,000 and incorporated the peer lending methodology. De Wit worked with him on this pilot program. This change resulted in the repayment rate climbing to 70%. The change in methodology energized de Wit to 186 Exhibit 3. Map of the Northern Province P O R T R A I T S of B U S I N E S S P R A C T I C E S in E M E R G I N G M A R K E T S BUILDING THE B O A R D at the S M A L L E N T E R P R I S E F O U N D A T I O N ( S E F ) The “Poverty and Inequality Report” (as commissioned by the South African Government) stated that in per-capita terms, South Africa was an upper-middle income country. 1997 per capita GDP stood at around U.S.$3,040. Despite this, the majority of households experienced poverty or were particularly vulnerable to falling into poverty. The country’s distribution of wealth was in fact among the most unequal in the world. Nineteen (19) million people lived in the poorest 40% of households, earning below R360 ($60) per adult per month. Ten million earned less than R192 ($32) per adult per month. In terms of the Human Development Index (HDI), South Africa ranks 86th along with countries such as Paraguay, Iran, Sri Lanka, and China. The Northern Province, the area in which the Small Enterprise Foundation operated, had a Human Development Index (HDI) equivalent to that of Zimbabwe which ranked 121st in the HDI and was in line with countries such as Lesotho and Namibia. According to the 1996 census, the total population of South Africa was 40.5 million. The population of the Northern Province was 5 Million. According to the results from this same census, for South Africa as a whole, 76.7% of the population was Black, 8.9% Colored, 2.5% Indian or Asian, 10.9% White, and 1% other or unspecified. For the Northern Province, the census data stated that 96.7% of the population was Black, .2% Colored, .1% Asian or Indian, 2.4% White, and .7% other or unspecified. Exhibit 4. South Africa and the Northern Province these organizations focused on the urban Johannesburg area. But de Wit realized that the rural population did not receive adequate financial services. He was determined to bring financial services to these rural poor. He identified the Northern Province as the poorest province of South Africa (see Exhibits 2, 3, 4 and 5), and selected this province as the place to start. By operating in South Africa’s poorest province, he could see if the methodologies that worked in Asia could also work in Africa. The Western Cape is South Africa’s wealthiest province. Cape Town, often described as the world’s most beautiful city, is the economic driver of this province. It is included for comparison purposes. The Northern Province, Eastern Cape, and Northwest Province are largely composed of former African Homelands, or Bantu states as they were known in apartheid times, and are home to large rural poor populations. The Northern Eastern Northwest Western Province Cape Province Cape No Schooling 37% 21% 23% 7% Secondary Education 4.5% 4.7% 4.2% 10.6% Unemployment 46% 48% 38% 18% Earning<R501($84) 41% 32% 31% 18% Earning >4500 ($750) 5.8% 8.5% 5.7% 12.4% Living in <3 rooms 29% 39% 33% 23% Cooking with wood 64% 38% \21% 4% Piped water in house 18% 25% 31% 76% Phone or Cell-Phone 8% 16% 17% 55% No Toilet 21% 29% 6% 5% Refuse removal 11% 34% 35% 84% Exhibit 5. Results of 1996 Poverty Census C A S E S for M A N A G E M E N T E D U C A T I O N Northern Province ranks near the bottom in nearly every category examined for the 1996 census. With his contacts in USAID, he felt that he could raise the necessary funding, but he needed help on the operations side. He had never been to the Northern Province and wanted to set up shop there. He realized that a good Board of Directors could help smooth the way. SEF in the Beginning John de Wit and Patrick Malatji founded SEF together in 1992. Their partnership sprouted from an act of kindness by de Wit several years prior to their first meeting. A member of the once illegal ANC3 party and community activist, Malatji usually made little time to meet with white South Africans. However, de Wit had unknowingly aided one of Malatji’s friends years earlier. In 1986, Mr. Malatji had been paying his friend Harry Ramaphosa’s university fees. In that year, Malatji was arrested and then imprisoned for two years under the Internal Security Act of 1984. Malatji’s activities in the then illegal ANC party resulted in security forces identifying him as a communist instigator. At the time John de Wit worked at GAF where Malatji’s friend Harry Ramaphosa also worked as a student intern. After Malatji’s detention, Ramaphosa approached de Wit for the favor of a loan, and de Wit agreed. Years later, this good deed would pay back dividends. When de Wit decided to begin operations in the Northern Province of South Africa, he realized he would need contacts there. De Wit contacted Harry Ramaphosa, a native of Tzaneen, and asked him to provide some names of people he thought he should contact to pursue his plan. The first person Ramaphosa suggested was Patrick Malatji. Malatji lived in the area, and de Wit learned 187 CASE STUDIES The Small Enterprise Foundation (SEF) is a non-profit NGO that commenced operations in 1992. The aim of the Foundation was to work towards the elimination of poverty and unemployment. This was accomplished through two programs, the Micro-Credit Program (MCP) and the Tshomisano Credit Program (TCP). MCP focused on existing but generally marginal micro-enterprises and provided them with micro-loans. TCP strictly targeted women who lived below half the poverty line. SEF employed a group-based lending methodology patterned after the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh. Potential members formed themselves into groups of five. The groups were rigorously tested on SEF procedures and knowledge of each other before they were officially recognized. Upon recognition, groups were eligible to apply for loans which they collectively guaranteed. SEF did not provide savings services. Instead, it required members of both programs to accumulate regular savings through a group Post Office Savings Account. SEF had no direct control of or access to the group savings. Through the savings plan, borrowers built up a fund that they could fall back on when they faced mishaps or tragedies. For 2/3 of the population of the Northern Province, self-employment was the only hope of generating an income. Small businesses struggled to survive due in part to a paucity of credit sources. SEF was established to respond to this need. Exhibit 6. Overview of the Small Enterprise Foundation that he was active in community development. After de Wit contacted him, Malatji contacted Ramaphosa to verify de Wit’s credentials. Ramaphosa shared the student loan story of years before and persuaded Malatji to make time for de Wit. Malatji and de Wit met, discussed their common objectives, and agreed to form SEF. Their goal mandated that SEF provide micro-credit to the rural poor in the Northern Province. An overview of SEF appears in Exhibit 6. SEF Today SEF has become a success. By the year 2000, SEF had signed on over 10,000 clients, extending loans to two different classes of the rural poor. In 1998, SEF was featured in a front-page article in The Wall Street Journal. De Wit himself had been named to the Advisory Board of a World Bank micro-finance initiative. His responsibilities to this Board required quarterly trips to either Europe or the United States to attend meetings. Things had changed since he had his vision of working to help earthquake victims. His micro-credit program (MCP) provided loans to existing operators of small businesses. A second program, Tshomisano Program (TCP) (Zulu for “working together”), provided loans to poor women who sought to be self-employed. The financial targets were being met, as shown in Exhibits 7 and 8. Though still losing money, SEF’s actual figures shown in Exhibit 8 were considerably better than what was projected for the year. If SEF continued along its current path, it would reach profitability in three years. Profitability represented one of the two primary goals of the organization. The second goal was to reach a client base of the poorest citizens of South Africa. Through its innovative outreach program, SEF had reached this goal as well. SEF’s Methodology While the poor may have initiative, ideas, and the will to become self-employed, they very often do not have the small amounts of capital needed to start a business. Likewise, the majority of those running micro-enterprises were unable to stabilize and expand their activities due to lack of capital. In order to receive a loan, an applicant had to form a group of five with four others who were interested in gaining access to SEF’s services. The strength of the group was rigorously checked and where weakness was detected, applicants were motivated to find alternate members. The group was then given preliminary recognition and began a series of training sessions that explained the credit and savings methodology, motivated applicants to begin regular savings deposits and dealt with the duties and responsibilities of group members. During the training process the group was introduced to the “center” concept. A center was the 2 weeks meeting of all groups from a section of a village. They were run under the leadership of an elected Center Committee. Once the group had been recognized by the center and completed its training, it would undergo a final recognition “test” Loan interest income Operational expense Interest paid Investment interest income Investments/cash Operational self-sufficiency 1999 R2 566 919 R4 613 809 R 73 653 1998 R1 026 690 R3 396 444 R 114 886 Percentage change 150% 35% (35%) R 429 542 R3 806 934 R 974 812 R5 067 755 (56%) (25%) 56% 30% $1 = 6R Exhibit 7. SEF Financial Indicators 188 P O R T R A I T S of B U S I N E S S P R A C T I C E S in E M E R G I N G M A R K E T S BUILDING THE B O A R D at the S M A L L E N T E R P R I S E F O U N D A T I O N ( S E F ) 1998/99 fiscal year Projections Net Interest Earned R 2,313,278 R 2,077,329 Branch Expenses R 1,483,673 R 1,652,424 time and money of traveling to town versus paying the higher prices to local merchants. MCP - Micro-Credit Program Loan Loss Provisions R 10,902 R 9,679 Zonal Office Expenses R 500,709 R 554,573 Net MCP R 317,995 (R 139,347) TCP – Tshomisano Program Net Interest Earned R 253,644 R 247,742 Branch Expenses R 538,060 R 678, 915 Loan Loss Provisions R 5,470 R 2,179 R 310,322 R 229,115 Net TCP (R 600,208) (R 662,467) Head Office Expenses R 1,505,792 R 1,912,605 Zonal Office Expenses Training R 223,735 Investment Income R 429,542 R 254,273 R 60,040 R 45,877 (R 1,642,638) (R 2,506,023) Interest Paid Net Profit/Loss Exhibit 8. SEF 1999 Results vs. Projections conducted by a senior manager. If recognized, the group could then apply for loans. Each member’s business plan was discussed and refined during the training, and each member applied for his/her own loan for his/her own income generating activity. All group members guaranteed the loan repayments of their fellow group members and could be called upon to assist any member who fell into arrears. Within a few days of disbursement, members were expected to utilize their loans in accordance with their pre-agreed business plans. Disbursements came in the form of checks. Clients had to cash their checks. They did this either by traveling to the nearest bank branch or by cashing it with a local merchant. Because of SEF’s focus on the rural poor, traveling to a bank usually required a day of travel to and from the nearest large town. Traveling involved taking public transport, if available, and this required an additional cash outlay, which cut into profits. After cashing the checks, clients could buy the inventory needed from large merchants in town. South Africa had a very developed retail environment. National chain stores similar to Wal-Mart operated in any town large enough to have a bank. Alternatively, cooperative local merchants would cash checks if the clients purchased their needed inventory from them. Prices of local merchants were often higher than those in town. Clients had to weigh the cost in C A S E S for M A N A G E M E N T E D U C A T I O N Group leaders checked that loans were used according to plan and the SEF Field Worker checked loan utilization on the first and second loans, and made spot checks thereafter. The principle aim of this process was to encourage members to assist each other and to demonstrate that utilizing loans in accordance with business plans was the first step towards success. Throughout the loan cycle, group leadership had responsibility for checking the progress of each member’s business. Results of these visits were reported at each biweekly center meeting. Towards the end of the loan cycle, the Field Worker assessed the growth of the businesses seeking loan renewal. The Field Worker then assisted them in determining an appropriate size for the next loan. SEF encouraged regular savings by requiring groups to open a savings account at a local post office. At center meetings, members were encouraged to save in this account. The average amount saved ranged from R2 ($.33) to R10 ($1.67) per member per meeting. This account was entirely controlled by the group. With the exception of a few loans made in a pilot program testing monthly payments, loans were repaid in bi-weekly installments. Members brought cash repayments to group meetings and group members pooled together their individual payments. The entire center’s payments were placed in a steel lock box. After the meeting was over, repayments were deposited into accounts SEF maintained at the Post Office. Group payments to savings were deposited into the group savings account. Money from SEF’s account was eventually transferred back to one of the banks that SEF used to issue disbursement checks. Ninety-seven percent (97%) of SEF clients were female. Three factors contributed to this heavily female client base. First, SEF focused on the poorest of the poor. In South Africa, the poor tended to be women. Econd, the organization of South African labor meant that men left the villages for jobs in the mines or in the large cities. They returned about once a month at “month-end” when they were paid. Often, if they came back at all, it was only for the big holidays such as Christmas and Easter. A majority of South African businesses closed the last two weeks of the year for the Christmas holidays. Easter was a four-day weekend. This meant that most of the time women were the only full-time residents of rural villages. Three, the Grameen Model loaned mostly to women, and in micro-finance circles women are viewed as better credit risks. 189 CASE STUDIES Typical enterprises included selling fruit and vegetables, new or used clothing, or starting small convenience shops and dressmaking. 18% of clients were involved in some form of manufacturing enterprise. De Wit felt proud of what SEF had achieved, but it had not been an entirely smooth trip. [A companion case, “Managing Decentralization at the SEF,” details some of the management challenges experienced in the face of rapid organizational growth.] The Board of Directors played a critical role in SEF’s success. Board members facilitated the commencement of operations in the rural areas and the crafting of the organization’s human resources policy. The first four Board members including de Wit had been stalwarts. They were there from the beginning, and they insured the organization remained true to its vision. John de Wit’s Goals for the Board Maintain the vision: The first function of the Board was as the guardians of the vision of the organization. For decades prior to the early 1990’s, South Africa operated in isolation. This isolation was the price South Africa paid for its apartheid politics. Other governments in the world, with few exceptions, enacted sanctions against it. With a mission to address the problems of the poor, micro-finance represented a new and radical idea. The group lending methodology and the idea that SEF could recover its costs and become profitable were untested ideas in the South African non-profit sector. The little aid that flowed to the poorer members of society resembled the traditional Victorian model of charity. Agencies simply gave people food, blankets, or medicine. Few talked of empowering the masses to solve their own problems. De Wit devoted the first few Board meetings to inculcating the Board with his vision. He wanted them to believe that they could be profitable, they could serve the poorest people, and they could empower them. Once the Board accepted this vision, he counted on them to insure the organization kept its focus. This challenge came from several sources. Once de Wit proposed allocating motorcycles to loan officers, but Board members asked if this adhered to the organization’s vision of sustainability. Could the cost of the motorcycles be recovered from the extra business they will generate? The Board deemed the answer to be no and rejected the proposal. The Board also helped SEF focus on loaning money to clients starting businesses but not to finance training or anything else that was not income producing. De Wit continually credited the Board for holding him to the original vision, articulated when he first asked them to join him and then fully presented in the first few meetings of the Board. He felt this focus helped SEF to achieve its success. secure permission from local leaders for SEF to operate. De Wit credited the Board members with this responsibility for a good portion of SEF’s success. De Wit expected members tied to the formal sector of the economy to smooth relations with the various formal financial institutions on which SEF depended. SEF disbursed all its loans via checks. Bank branches were few and far between in rural South Africa, so SEF needed to cultivate relationships with several banks to enable SEF customers to cash checks at the banks nearest them. A requirement of SEF membership was that members share a savings account. The People’s Bank, the first banking institution where SEF tried to get members to open accounts, eventually rejected the business. SEF needed the cooperation of the Post Office to handle repayments and savings deposits. These large volume transactions became a burden to the Post Office. But Post Office management devised new procedures to deal with SEF members. Connections that Board members maintained with the head of the Post Office Bank facilitated the development of these procedures. Board members also facilitated start-up funding. SEF looked to International Development agencies for grants, socially responsible banking institutions for loans- some at favorable interest rates-and South African Development banks for additional loans. SEF succeeded very well in raising the funds it needed because Board members who had experience working with these organizations eased the process. Help with management: De Wit had no experience growing a start-up organization. He depended on Board members for advice on how to expand. He expected Board members to play an active role in evaluating and hiring new management personnel. The role of human resource manager represented one management role for the Board. A second management role was helping develop the organizational structure. De Wit wanted to build a Board with sufficient management experience to guide him in designing a formal organizational structure of the foundation. Other qualities: De Wit stressed that he wanted Board members to be people of integrity who wanted to participate in the growth of the organization. He consciously chose people who did not have a high profile and were willing to work hard to build the organization. De Wit envisioned a Board of at least five members and eventually six. Members were busy people and he wanted to insure that a quorum could always attend meetings. Despite the impulse to have an odd number of members to provide a tie-breaking vote, De Wit preferred that the Board operate by consensus. The Board was small enough and he respected the input of all its members enough to want them all to agree on operational policies for the organization. Facilitate operations: De Wit expected the Board to facilitate SEF operations in two ways. Fist, local Board members were expected to introduce SEF in the local communities and 190 P O R T R A I T S of B U S I N E S S P R A C T I C E S in E M E R G I N G M A R K E T S BUILDING THE B O A R D at the S M A L L E N T E R P R I S E F O U N D A T I O N ( S E F ) Formation of the Board rural post offices adopting new procedures to work with SEF. One by one the Board expanded to five people. De Wit and Malatji were the original members. Nathanial Ramalepe became the third member. As a local resident of the Tzaneen area, he brought knowledge of the community. His appointment lent creditability to the organization as he was well known in the community. He also knew a great deal about the area and the people who lived there. He helped smooth relations with local government officials and steered de Wit away from involvement with some opportunists. The fourth Board member was Daphne Motsepe. Daphe was well connected in the political and economic circles of South Africa. She worked in the finance department of National Sorghum Breweries. She also served on the Board of the Women’s Development Bank along with the wife of current President Mbekei, Nelson Mandela’s successor. She also served on the Board of the Post Office. The link proved important for SEF’s development as SEF’s clients used the Post Office Bank to deposit both their loan repayments and their group savings accounts contributions. Security issues in South Africa made de Wit wary of SEF field staff transporting large amounts of cash, but the SEF system placed a strain on the post office system. A center would have loan repayments from up to 40 individuals as well as savings deposits from 8 groups. The size of each of these transactions could be as low as R10 ($1.67). The post offices in the rural areas were not computerized and all transactions involved laborious manual entries. Motsepe’s position on the Board smoothed relations with the service and led to Name/Gender/Race John De Wit Education The fifth Board member was Lynn Anderson. She was a friend of de Wit’s from his Get Ahead days. She brought micro-finance experience and connections to the funding sources. She resigned after two years of service, explained below. The sixth Board member was Gabriel Nackan, the first employee of SEF and a designer of its operating procedures. He also resigned and left a year later. The last Board member appointed was Marie Kirsten, another contact from Get Ahead. Now working as a consultant to the South African micro-finance industry, she had micro-lending experience and connections to donors. Former Board Members Lynn Anderson: BS, Finance.Worked in small business lending with Mr. de Wit in the Get Ahead Foundation. Lynn left the Board after serving two years. In her official resignation letter, Lynn stated one of her reasons was to maintain a black majority on the Board. The Board had elected to expand and nominated Gabriel Nackan as the third white member, in addition to Lynn Anderson and John de Wit. Mr. de Wit felt that Lynn’s real reasons for leaving were based on her discomfort with the responsibilities of being a Board member. Ms. Anderson was appointed to the SEF Board in 1993 and left in 1994. Gabriel Nackan: Mr. Nackan formerly worked as a consultant with Mr. de Wit after he left Get Ahead. He returned to work with Mr. de Wit in the formation of SEF after getting his MBA in Europe. Mr. Nackan designed many of the operational systems Profession Year Joined Resides BS Engineering Executive director, SEF 1991 Tzaneen High School Graduate ANC party official, Board member 1991 Phalaborwa 1992 Tzaneen 1993 Johannesburg 1996 Johannesburg Male/White Patrick Malatji Male/Black of several development organizations in Northern Province Nathanial Ramalepe BA, Education Male/Black Principal of farm school in Tzaneen area. Board member of Northern Province rural education project Daphne Motsepe MBA Senior Financial Manager, Female/Black National Sorghum Breweries. Board Member,Women’s Development Bank, South African Postal Service. Former Board Member, Get Ahead Foundation Marie Kirsten MA, Economics Female/White Independent Consultant. Formerly employed managing micro-finance program at the Get Ahead Foundation Exhibit 9. Board Member (in order of Joining) C A S E S for M A N A G E M E N T E D U C A T I O N 191 CASE STUDIES at the Small Enterprise Foundation. In order to insure that Mr. Nackan received the recognition he deserved for these efforts, he was appointed to the Board of Directors. He later left SEF to join Price Waterhouse (later PricewaterhouseCoopers) as a consultant. Mr. de Wit cited tension between Mr. Nackan and himself as the reason Nackan left and resigned from the Board. He had joined the SEF Board in 1994 and left in 1995. Contributions by Individual Board Members De Wit credited the Board for several facets of SEF’s success. Specifically, he highlighted the efforts of Mr. Malatji, Mr. Ramalepe and Mr. Nackan. In the early 1990’s in South Africa, there was a considerable degree of distrust between white and black residents. Mr. Malatji and Mr. Ramalepe were respected community leaders in the Northern Province. Their presence on the Board lent credibility to SEF’s efforts in the eyes of the community. More than that, both these individuals actively introduced SEF into the local communities. The Northern Province is comprised of many former homelands that local ethnic groups governed on their own under the apartheid system. These homelands were known as tribal homelands, and tribal governments still operated at the local level. That meant that traditional non-elected leaders governed the rural areas in the Northern Province. SEF needed the consent of these leaders to commence operations in these areas. Mr. Malatji and Mr. Ramalepe sought these leaders out and explained SEF’s mission. Mr. Malatji believed firmly that politics caused much of the economic inequality in South Africa. He saw SEF’s program as a way to address these past inequalities. He thus enthusiastically took this mission to the field, insuring SEF’s acceptance by the traditional leaders. Mr. Malatji and Mr. Ramalepe, both raised in the Northern Province, also prevented SEF from getting entangled with unscrupulous individuals. Mr. de Wit hailed from Cape Town so he did not know members of the community well. On several occasions, Mr. Malatji or Mr. Ramalepe intervened to prevent individuals with reputations for theft or corruption from becoming associated with SEF. Several times such individuals had presented themselves to de Wit looking for positions as Board members, employees, or informal community liaisons. Mr. Nackan did yeoman’s work in developing a very simple yet effective management reporting system. The Small Enterprise Foundation operated without computers except in the head office. Mr. Nackan developed a manual system for tracking clients and loan repayments. Keeping good track of clients enabled SEF to develop a reputation for good client service. SEF issued checks to the right clients at the right time, an area where many developing micro-finance institutions stumble. 192 Mr. de Wit credited this system for helping keep SEF’s dropout rate low. Outside South Africa, in the micro-finance world, SEF developed a reputation as an innovative and well-run organization. Inside South Africa, however, it was not well known. Potential Board members had to be identified and approached. They needed to learn about micro-finance. They needed to understand and support SEF’s mission of empowering the poor. Most importantly, they needed to contribute in some way to the development of the organization. Finding talented and capable people willing to join the Board had not proved difficult. De Wit and Malatji used their contacts and the Board grew easily to five. However, the Board still remained short of the envisioned six members. Both Malatji and de Wit had exhausted their lists of personal contacts to identify suitable Board members. De Wit asked himself what made the previous members leave and whom should he choose as its next members? Outside consultants cited the involvement and competency of the Board among SEF’s positive attributes. De Wit wanted this positive momentum to continue. He had to consider the needs of the organization and where to find suitable candidates for the potential fifth and sixth Board seats. By tradition the Board had a black majority, so this factor also weighed in his evaluation of potential candidates. Appendix Relevant Web Links SEF’s Home Page: www.sef.co.za Profile of John de Wit: www.ashoka.org/viewprofile1.cfm?PersonId=522 History of the ANC: www.anc.org.za/ancindex.html South African Statistics: www.statssa.gov.za/ Grameen Bank: www.grameen.org USAID Micro-finance in South Africa: www.usaid.gov/procurement_bus_opp/procurement/so5.doc 1. This case was written by David S. Berkowitz of the University of Colorado at Denver under the supervision of Professor Richard Linowes of the Kogod School of Business at American University in Washington, D.C. It is intended as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. 2. The Rand (R) is the standard unit of currency. At the time of writing, $1=R6 3. In 1950, the ANC (African National Congress), founded in 1912, began the defiance campaign. The Campaign was the beginning of a mass movement of resistance to apartheid. Apartheid aimed to separate the different race groups completely through laws like the Population Registration Act, Group Areas Act and Bantu Education Act, and through stricter pass laws and forced removals. In response to this movement the government banned the ANC in 1960. The ANC began an armed struggle against the government in 1961. As a result of the banning, membership in the ANC and any activities on its behalf were made illegal. In February 1990, the regime was forced to legalize the ANC and other organizations. P O R T R A I T S of B U S I N E S S P R A C T I C E S in E M E R G I N G M A R K E T S