The Offshore Services Global Value Chain

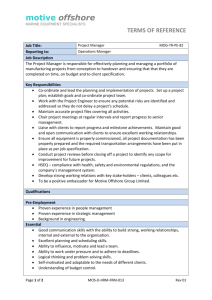

advertisement