OBSERVING TASK AND EGO INVOLVEMENT IN A CLUB

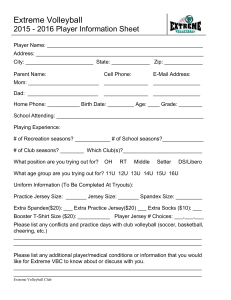

advertisement