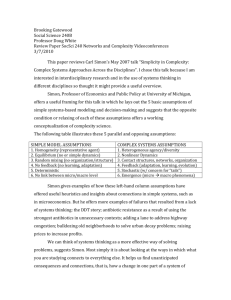

philosopher of the organizational life-world

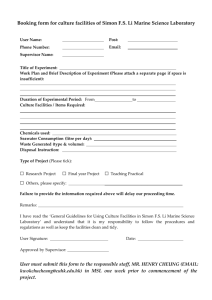

advertisement