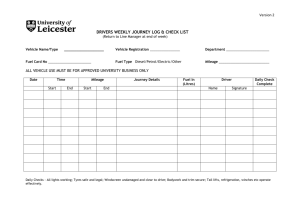

The Per-mile Costs of Operating Automobiles and Trucks

advertisement