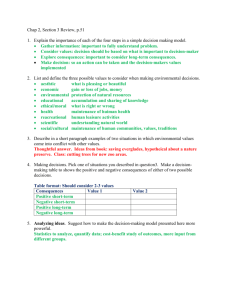

Chapter 3 - Craig School of Business

advertisement