Creolization in Southwest Florida: Cuban Fishermen and “Spanish

advertisement

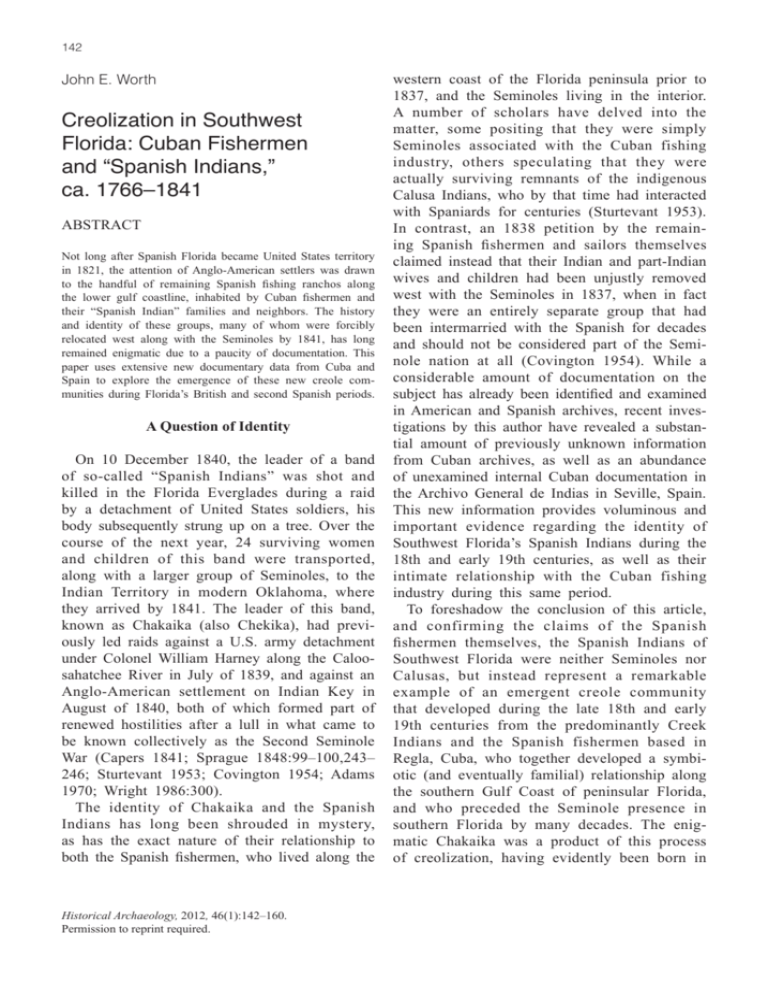

142 John E. Worth Creolization in Southwest Florida: Cuban Fishermen and “Spanish Indians,” ca. 1766–1841 ABSTRACT Not long after Spanish Florida became United States territory in 1821, the attention of Anglo-American settlers was drawn to the handful of remaining Spanish fishing ranchos along the lower gulf coastline, inhabited by Cuban fishermen and their “Spanish Indian” families and neighbors. The history and identity of these groups, many of whom were forcibly relocated west along with the Seminoles by 1841, has long remained enigmatic due to a paucity of documentation. This paper uses extensive new documentary data from Cuba and Spain to explore the emergence of these new creole communities during Florida’s British and second Spanish periods. A Question of Identity On 10 December 1840, the leader of a band of so-called “Spanish Indians” was shot and killed in the Florida Everglades during a raid by a detachment of United States soldiers, his body subsequently strung up on a tree. Over the course of the next year, 24 surviving women and children of this band were transported, along with a larger group of Seminoles, to the Indian Territory in modern Oklahoma, where they arrived by 1841. The leader of this band, known as Chakaika (also Chekika), had previously led raids against a U.S. army detachment under Colonel William Harney along the Caloosahatchee River in July of 1839, and against an Anglo-American settlement on Indian Key in August of 1840, both of which formed part of renewed hostilities after a lull in what came to be known collectively as the Second Seminole War (Capers 1841; Sprague 1848:99–100,243– 246; Sturtevant 1953; Covington 1954; Adams 1970; Wright 1986:300). The identity of Chakaika and the Spanish Indians has long been shrouded in mystery, as has the exact nature of their relationship to both the Spanish fishermen, who lived along the Historical Archaeology, 2012, 46(1):142–160. Permission to reprint required. western coast of the Florida peninsula prior to 1837, and the Seminoles living in the interior. A number of scholars have delved into the matter, some positing that they were simply Seminoles associated with the Cuban fishing industry, others speculating that they were actually surviving remnants of the indigenous Calusa Indians, who by that time had interacted with Spaniards for centuries (Sturtevant 1953). In contrast, an 1838 petition by the remaining Spanish fishermen and sailors themselves claimed instead that their Indian and part-Indian wives and children had been unjustly removed west with the Seminoles in 1837, when in fact they were an entirely separate group that had been intermarried with the Spanish for decades and should not be considered part of the Seminole nation at all (Covington 1954). While a considerable amount of documentation on the subject has already been identified and examined in American and Spanish archives, recent investigations by this author have revealed a substantial amount of previously unknown information from Cuban archives, as well as an abundance of unexamined internal Cuban documentation in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain. This new information provides voluminous and important evidence regarding the identity of Southwest Florida’s Spanish Indians during the 18th and early 19th centuries, as well as their intimate relationship with the Cuban fishing industry during this same period. To foreshadow the conclusion of this article, and confirming the claims of the Spanish fishermen themselves, the Spanish Indians of Southwest Florida were neither Seminoles nor Calusas, but instead represent a remarkable example of an emergent creole community that developed during the late 18th and early 19th centuries from the predominantly Creek Indians and the Spanish fishermen based in Regla, Cuba, who together developed a symbiotic (and eventually familial) relationship along the southern Gulf Coast of peninsular Florida, and who preceded the Seminole presence in southern Florida by many decades. The enigmatic Chakaika was a product of this process of creolization, having evidently been born in 143 John E. Worth—Creolization in Southwest Florida one of these Cuban fishing ranchos under the name Antonio, employed during his early life in both fishing and sailing between Florida and Cuba (Fitzpatrick and Wyatt 1842), and whose 1839 uprising was in large part a response to the destruction of the Cuban fisheries and the forced removal of their Spanish Indian inhabitants during the previous three years. Despite their official inclusion among the Seminoles removed from Florida during the Second Seminole War, the Spanish Indians were in fact the mixed-blood offspring of Spanish fishermen and early Creek and Yamasee immigrants to the Southwest Florida coast, many of whom were baptized in Cuba, and whose lifestyles by the 1830s were apparently as much or more Spanish than Indian. In sum, these Spanish Indians and the Cuban fishing ranchos they lived in represent an important and largely unstudied case of creolization during the colonial period. Although the abrupt and tragic ending of these creole communities during the 1830s makes it impossible to say how this process might have evolved over time, a review of their origins provides important insights into the process of creolization in general, especially as it evolved in the context of the maritime connection between Cuba and South Florida. The concept of creolization has recently been explored by a number of researchers as a useful approach to exploring the issues surrounding emergent multiethnic cultural identities in the context of the European colonial era (Deagan 1973, 1983, 1996; Ewen 1991, 2000; Ferguson 1992, 2000; Mouer 1993; Lightfoot and Martinez 1995; Cusick 2000; Gundaker 2000; Loren 2000; Mullins and Paynter 2000; Webster 2001; Voss 2005). Creolization challenges more traditional notions of culture contact that derive from simple hierarchical dichotomies such as colonizer/colonized, colonist/native, core/periphery, and dominant/subordinate, including acculturation and transculturation studies (Redfield et al. 1936; Quimby and Spoehr 1951; McEwan and Mitchem 1984; Deagan 1998). Instead, creolization offers a conceptual framework that recognizes the unique and often-innovative nature of cultural transformation within the frontier zone itself, redefined as “socially charged places where innovative cultural constructs are created and transformed,” and as “zones of cultural interfaces in which cross-cutting and overlapping social units can be defined and recombined at different spatial and temporal scales of analysis” (Lightfoot and Martinez 1995:472). More narrowly, creolization may also be defined as “a process by which ‘mixed-race’ individuals constructed new social identities to make a social, economic, and/or political place for themselves in colonial society” (Loren 2000:85). The end result of this process could fundamentally transform the social landscape; as noted by Voss (2005:465), “this transition—from a pluralistic constellation of colonial racial monikers to a unified regional identity—is no less than ethnogenesis, the creation of a new ethnicity forged through the experiences of colonization and culture contact.” Ultimately, the concept of creolization returns a degree of agency to the individuals and groups who might otherwise be viewed as unwitting pawns in the colonial clash that marked culture contact between the Old World and the New after 1492. As individuals and communities navigated an uncharted course through the dynamic colonial landscape, these new cultural formations not only drew upon the traditions of previously disparate cultures, but simultaneously generated novel adaptations to completely new circumstances. The Spanish Indians of Southwest Florida were one such result of the colonial era. The Cuban Fishing Industry Space considerations in this article only permit a brief overview of what is a considerable amount of new and detailed information, mostly as-yet unpublished. Since the origins of the Spanish Indians are integrally linked to the Cuban fishing industry in southern Florida, it is important to note that Spanish fishing vessels operating out of the vicinity of Havana had apparently been fishing in Florida waters with permission from the indigenous Calusas by no later than the 1680s, continuing and expanding after the evacuation of the Calusas to the Florida Keys between 1704 and 1711 in response to Yamasee and Creek Indian slave raids (Worth 2003, 2004, 2009). By the 1740s, Cuban-based fishing vessels routinely employed guides and fishermen from what few indigenous South Florida groups were living on or near the Florida Keys (Hann 1991:325–431; Worth 2004), but continued aggression from Creek raiders ultimately pushed 144 these remaining “Keys Indians” south to Key West itself. From there, in May of 1760, fewer than 70 survivors finally fled permanently to Cuba, leaving the entire Florida peninsula to the English-allied Creeks, who had even been attacking Cuban fishing vessels during the course of the Seven Years’ War beginning in 1756 (Worth 2003). The 1762 Creek attack and kidnapping of the passengers of a Spanish vessel anchored at Key West on its way to Havana confirmed Creek control of this last Calusa stronghold along with the entire coastal fishing zone of South Florida (Feliu 1762). Despite the 1763 surrender of Florida to British control (Gold 1964, 1969), the Cuban fishing industry continued largely unabated throughout the next two decades of Florida’s British period. Florida’s peninsular Gulf Coast had always remained largely outside the effective reach of Spanish colonial authorities, and this did not change under British rule, making it easy for Cuban fishermen to continue their seasonal fishing voyages unhindered by the change in colonial administration. Only one major obstacle remained: the replacement of allied Calusas and other indigenous South Florida Indians by hostile Creeks, who were in a far better position either to impede or facilitate Cuban fishing than British authorities. Only a few years passed before negotiations seem to have been opened between Spanish authorities in Havana and representatives of the Lower Creek tribe, known to the Spanish as the province of Coweta, or most commonly as the Uchise Indians. The earliest shipboard trip to Havana by Lower Creek emissaries that so far can be documented during the British period was during 1766 (Boyd and Latorre 1953:93). After the British withdrawal from the old Spanish fort at St. Marks in 1769, however, the fort was seized by longtime Spanish ally Tunape, the Coweta-born chief of the nearby Lower Creek town known as Tallahassa Taloofa, then located at San Luís de Talimali (Boyd and Latorre 1953:126–127). Subsequently, a series of Creek emissaries were sent between 1771 and 1776, finally culminating in a 1777 visit by Tunape himself, all facilitated by Cuban fishing vessels (Boyd and Latorre 1953). In Tunape’s translated oral speech, he requested that the Spaniards provide him a Spanish flag to raise over the fort at St. Marks, and initiate a routine maritime traffic HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 46(1) between Havana and St. Marks in order to cement the proposed diplomatic and commercial alliance, including munitions and other supplies. Claiming to be able to defend against English settlement along the entire Atlantic coastline of peninsular Florida from Sebastian Inlet to Boca Raton, and on the Gulf Coast from Cape Sable to St. Joseph’s Bay, Tunape’s pro-Spanish Creek faction laid claim to all of Florida’s coasts between English settlements at St. Augustine and Pensacola. Tunape also made specific note that an Uchise faction called Cimarrones (most likely the Seminoles) had sided with the English against the American revolutionaries in Georgia, in violation of the policy of the emperor of Coweta. Though Spanish assistance remained somewhat limited until the formal declaration of war between Spain and England in 1779, beginning in July of that year Havana authorities began to include arms and munitions in their routine gifts to Creek visitors (Navarro 1779, 1780). Even at this early date, Hispanophile Creeks affiliated with the Muskogee-speaking Coweta town had begun to establish relations with Spanish Havana, while Anglophile Creeks affiliated with Hitchiti-speaking towns in northern Central Florida were firmly allied to British St. Augustine (Sturtevant 1971:102; Calloway 1995:249). From this early factional divide among the Florida Creeks emerged the later distinction between the interior Seminoles and the coastal Spanish Indians. Both had Creek origins, but their histories diverged prior to the American Revolution. Careful review by this author of Cuban records in both the Archivo Nacional de Cuba in Havana, and the Archivo General de Indias in Seville provides clear documentation both of the regularity and volume of maritime traffic between Florida’s peninsular Gulf Coast and Havana Bay, growing incrementally through the 1780s, and particularly after the return of Florida to Spanish control in 1783. Not only are there frequent letters and other correspondence referring to diplomatic visits by Florida Indian visitors, but the financial account records of the Havana Intendencia General are full of expense receipts for the costs of transport, lodging, rations, and gifts provided to what eventually became literally hundreds of Indian visitors each year, all transported back and forth by privately owned Cuban fishing schooners and sloops. John E. Worth—Creolization in Southwest Florida Selected examples from all periods are cited here (de Arriaga 1771; de Fondesviela y Ondeano 1773, 1774, 1775a, 1775b, 1776a, 1776b, 1777a, 1777b; Eligio de la Puente 1777a; Navarro 1779; de Urriza 1782; Gálvez 1783; de Cárdenas 1786, 1787; del Río 1789a, 1789b, 1789c; Peñalver y Cárdenas 1793a; de Arango 1796a, 1797a, 1798a; de Zunzunegui 1802; de la Hoz 1803; Gómez Rombaud 1805a, 1805b, 1805c; de Aguilar 1810a, 1810b; de León 1818a, 1818b, 1819a, 1819b, 1819c, 1819d, 1819e, 1819f, 1820a, 1820b, 1820c, 1820d, 1820e, 1820f, 1821, 1823; Ramírez 1816a, 1816b, 1816c, 1816d, 1816e, 1818, 1819a, 1819b, 1820a, 1820b, 1820c, 1821a, 1821b; de Cagigal 1819; Fernández 1821). Many of these receipts contain lists of the names of each Florida Indian visitor, and examination of these names indicates that virtually all those that can be identified appear to have been either Creek or Hitchiti in linguistic origin (Jack Martin 2004, pers. comm.). Without going into extensive detail here, these records and others allow a remarkably rich portrait of the Cuban fishing industry in South Florida to be reconstructed, providing important details regarding the emergence of the creole communities ultimately inhabited by the Spanish Indians under consideration here (Dodd 1947; Covington 1959; Hammond 1973; Almy 2001; Worth 2004). During the late 18th century, the South Florida fishing fleet was generally comprised of perhaps 10 or 12 shallow-draft sailing vessels based in the fishing community of Regla, just across the harbor from downtown Havana. During the late fall and winter months, generally extending from October or November through February or March, the fishermen would sail north to the Florida coastline, focusing in particular on what was called the “Coast of Tampa,” including the “Port of Sanibel” and “Port of Tampa,” and to a certain extent also including the Florida Keys and the lower Atlantic coastline of South Florida (Figure 1). There they would spend four or five months netfishing in the rich estuaries of Charlotte Harbor, Tampa Bay, and others, salting their catch of mullet and other fish. Throughout these annual fishing seasons, hundreds of Florida Indian visitors went from Florida to Havana and back (see Figure 2 for the monthly distribution of a sample of these visits). Toward the beginning of the Lenten 145 season, which independent records indicate was the season of peak demand for fish in Havana, the vessels would return to sell their catch, which contributed a substantial portion of the fish available for Havana (Alonso 1760; Eligio de la Puente 1777b; de las Casas 1793). In the off season, these same vessels were employed in transporting salt from the rich production facilities at Cayo Sal (in the modern Bahamas) and Punta de Hicacos (on the northern coast of Cuba). Records indicate that vessels would make multiple trips loaded with salt, typically extending between May and August or September, ending just before the peak of hurricane season, when the vessels would presumably be sheltered and idle (see Figure 3 for the monthly distribution of these salt sales in Havana); voluminous 18th-century salt-trade records include the examples cited here (Peñalver y Cardenas 1774a, 1777a, 1778a, 1779a, 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783, 1785, 1786, 1787a, 1789, 1791, 1792, 1793b, 1794, 1795; de Arango 1796b, 1797b, 1798b), and selected fish-purchase records are cited here (Peñalver y Cardenas 1769, 1771, 1772, 1773, 1774b, 1775, 1776, 1777b, 1778b, 1779b, 1787b, 1788; Pamanes 1780; Galeano 1799; de Zunzunegui 1800, 1801). During the late 18th century, Cuba’s South Florida fishing fleet seems to have been strictly seasonal, and it was during their winter voyages that Spanish-allied Creeks would meet and trade with these fishing vessels, commonly making trips of a month’s duration or more to visit Havana for an audience with the Spanish governor and returning with an array of gifts, all authorized and reimbursed by the Spanish treasury. At some point by the turn of the century, however, these seasonal interactions evolved into something more, eventually crystallizing into a number of year-round fishing communities called ranchos located on coastal islands and mainland shores between Estero Bay and Tampa Bay. By the first decades of the 19th century, much of the Cuban fishing community actually resided in these Florida ranchos, voyaging to Cuba only to sell their catch or to bring family members for church sacraments (though all such groups seem to have been sent back with gifts and supplies at the cost of the Spanish treasury). At least one, José María Caldez, stated in 1833 that he had resided at his Useppa Island rancho for 45 years, suggesting that he 146 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 46(1) FIGURE 1. Map of Florida and Cuba. (Map by Dan Hughes, 2010.) may have established at least a seasonal residence there by 1788, though he also claimed to have visited the island before the American Revolution (Whitehead 1832; Monroe County Clerk of the Circuit Court 1833:442). As one example among a number of other prominent Cuban fishermen documented during this period, Caldez was recorded as the captain of vessels carrying Florida Indians to Havana at least as early as 1805, and regularly thereafter (Table 1). By the time of the 1821 transfer of Florida to U.S. jurisdiction, he and most of the Cuban fishermen had put down such extensive roots in Florida that they chose to remain in their ranchos as expatriates, some even applying unsuccessfully in 1828 for land grants based on prior occupation (Dickins and Forney 1860:107–109). The Spanish Indians Detailed review of baptismal records of nonwhites from the church of Nuestra Señora de Regla in Regla, Cuba, reveals that between 1807 and 1827, a total of 30 baptisms were performed on Florida Indians, including 20 born to Spanish husbands and Indian wives, 5 born to Indian women with unnamed fathers, and 3 born to Indian parents (Table 2). The Spaniards were all native to a number of cities in Spain (Asturias, Ferrol, Granada, La Palma), Mexico (Campeche), Cuba (Havana), and other locations (Caracas, Cartagena, Costa Firme, New York), and the Indians were native to a range of named towns including several known or thought-to-have-been Cuban fishing ranchos, John E. Worth—Creolization in Southwest Florida FIGURE 2. Monthly frequency of Florida Indian arrivals in Havana, 1792–1821. (Graph by author, 2010.) FIGURE 3. Monthly frequency of salt-ship arrivals in Havana, 1792–1821. (Graph by author, 2010.) 147 148 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 46(1) TABLE 1 SELECTED REFERENCES: FLORIDA INDIAN GROUPS ARRIVING IN HAVANA ON VESSELS CAPTAINED BY JOSÉ MARÍA CALDEZ, 1805–1823 Year Day/ Month Vessel Type Vessel Name Number of Indians Origin Notes Source(s) 1805 08/12 Balandra Santa Rosa de Lima 2 Bahia de Tampa – Gómez Rombaud 1805b 1805 12/21 Balandra 8 08/20 Goleta Bahia de Tampa Costa de Tampa – 1816 Santa Rosa de Lima La Concepcion – Gómez Rombaud 1805c Ramírez 1816a 1816 11/10 Goleta 1818 02/19 Balandra 1819 02/20 1819 4 La Concepcion Nuestra Señora del Rosario 18 Costa de Tampa – Ramírez 1816d 11 Bahia de Tampa – Ramírez 1818 Balandra Nuestra Señora del Rosario 78 Costa de Tampa Five caciques requested gifts before 02/25 Ramírez 1819a 07/13 Goleta Nuestra Señora del Rosario 15 – Ship arrived 07/08; Casique Opoijacho (Talcicalque) requested gifts 07/17 Ramírez 1819b, de León 1819a 1819 12/20 Goleta Nuestra Señora del Rosario 55 – Casiques Uquilisinijá (Uchises), Capichalajolá (Balgamos), and Cosafamico (Cosaches) requested gifts 12/22 de Cagigal 1819; de León 1819d 1820 08/26 Goleta Nuestra Señora del Rosario 8 Costa de Tampa – Ramírez 1820a 1820 11/25 Goleta Nuestra Señora del Rosario 78 Costa de Tampa Ship arrived 11/22; cacique Uchisimico (Uchisa) requested gifts on 11/24 Ramírez 1820b, 1820c; de León 1820d 1821 01/13 Goleta Nuestra Señora del Rosario 133 Costa de Tampa Cacique Mastonaque/ Mastoncique requested gifts 01/15 Ramírez 1821a, 1821b 1821 07/28 Goleta Nuestra Señora del Rosario 10 Costa de Tampa – Fernández 1821 1823 12/23 Goleta Nuestra Señora de Regla 10 Costa de Tampa 6 males, 4 females named de León 1823 149 John E. Worth—Creolization in Southwest Florida TABLE 2 BAPTISMS OF FLORIDA INDIANS IN REGLA, CUBA, 1807–1827 Date Child Notes Source 01/29/1807 Petrona Nugert Born July 1804, native of Pueblo of Ochecey Cortés y Salas (1807[1]:73) 01/29/1807 Lucia Nugert Born ca. 1806, native of Pueblo of Ochecey Cortés y Salas (1807[1]:74) 03/26/1810 María de Regla Born ca. 1798–1810, native of Apalache Cortés y Salas (1810[1]:220) 08/28/1814 Benita Andrea Ferreyro Born May, 1814, native of Pueblo of Tampa Cortés y Salas (1814[1]:234) 02/19/1815 Antonio María Peña Cortés y Salas (1815[1]:258) 02/19/1815 Francisco María Peña Born ca. 1812–1813, native of Pueblo of Tamasle Born 12/1813, native of Pueblo of Tamasle 03/18/1817 José del Carmen Born 03/15/1817 in Regla, Cuba, parents native to Pueblos of Choco[nile] and San Juan Cortés y Salas (1817[1]:396) 11/16/1817 Juana Born 11/04/1817, native of Punta Rasa Cortés y Salas (1817[1]:446) 11/28/1817 José Born 09/01/1817, native of Pueblo of San Juan Cortés y Salas (1817[1]:449) 12/25/1817 Juan Bautista Gonzáles Born 09/01/1817, native of Punta Rasa Cortés y Salas (1817[1]:451) 02/25/1819 José María Doroteo Godoy Born 02/06/1817, native of Punta Rasa Cortés y Salas (1819[1]:549) 06/09/1819 Primo Born 1805, native of Chata Cortés y Salas (1819[1]:576) 09/17/1819 Ana Josefa? Born 1815, native of Pueblo de los Chataes Cortés y Salas (1819[1]:598) 11/06/1819 Manuel Born 1818?, native of Pueblo of Simananca Cortés y Salas (1819[1]:609) 01/10/1820 Francisca Born ca. 1817, native of Pueblo of Tibaesasa Cortés y Salas (1820[1]:633) 01/10/1820 María de los Dolores Born 1819, native of Pueblo of Tibaesasaa Cortés y Salas (1820[1]:634) 02/04/1820 María del Carmen Rey Cortés y Salas (1820[1]:646) 02/04/1820 María Cecilia Peña Born 07/16/1818, native of Pueblo of Choconile Born 11/22/1819, native of Pueblo of Choconile 09/19/1820 José Ygnacio Cortés y Salas (1820[1]:1,039) 11/30/1820 Marcelina Felix 11/30/1820 Sebastiana Felix 11/30/1820 María Montes de Oca Born 03/19/1817, native of Cayo de Tio Cespes Born 06/02/1817?, native of Pueblo of Choconil Born 01/20/1820, native of Pueblo of Choconil Born 07/21/1820, native of Pueblo of Choconil 11/30/1820 Francisca de Paula Narváes Born 04/02/1820, native of Pueblo of Choconil Cortés y Salas (1820[1]:1,059) 12/04/1820 Tereza Fabiana Born 1820, native of Pueblo de los Uchises Cortés y Salas (1820[1]:1,063) 01/20/1821 Fernando González Born ca. 1818, native of Cayo de Tio Zespas Cortés y Salas (1821[1]:1,075) 01/20/1821 Ana Masearreño Born 05/07/1820, native of Cayo de Tio Zespas Cortés y Salas (1821[1]:1,076) 01/21/1823 Yldefonso Contreras Born 01/23/1820, native of Apalache Cortés y Salas (1823[1]:1,286) 02/17/1825 Benito Montes de Oca Born 02/11/1824, native of Pueblo of Choconil Cortés y Salas (1825[2]:196) 01/17/1827 Rita de los Angeles Montes de Oca Born 05/22/1826, native of Pueblo of Sanibel Cortés y Salas (1827[2]:362) 01/17/1827 María de la Merced Castillo Born 09/24/1820, native of Sanibel Cortés y Salas (1827[2]:363) Cortés y Salas (1815[1]:259) Cortés y Salas (1820[1]:647) Cortés y Salas (1820[1]:1,056) Cortés y Salas (1820[1]:1,057) Cortés y Salas (1820[1]:1,058) 150 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 46(1) including Useppa Island, Punta Rasa, Sanibel, and Tampa. This relatively small selection of baptisms performed in Cuba must have only been a tiny sample of the multiethnic children and families living in the ranchos of Southwest Florida, as implied by a number of contemporary sources, including an 1831 journal entry by Key West customs inspector William Whitehead noting that the women at the fisheries were “all of the Indian race,” with “the colour of [the children’s] skin betraying the mixed blood of the Spaniard and the Indian” (Whitehead 1832; Peters 1965:33–38). In an 1835 letter, American William Bunce provided important details regarding the extensive intermarriage among the inhabitants of his recently established fishery at the mouth of the Manatee River: At my rancho or fishing place I have in my employment about ten Spaniards and twenty Spanish Indians; most of the latter have been born and bred at the rancho on the coast, speak the Spanish language, and have never been in the country ten miles in their lives; their only mode of living is by fishing with the different Spanish companies, from August until March; during summer they cultivate some small spots of land in the neighborhood of their working place. They do not hunt, and depend upon their cast nets for support; there are many more at the other ranchos, say, Caldees, Cayo, Pelow, Ponte Rasa, and Eslava; only myself and Caldees have worked this season on account of the dull sale of fish at Havana, owing to the late cholera. All my white Spaniards have Indian families, and some of them have children and grandchildren. Many of the Spanish Indians have wives from the Nation. There are several Indians that have been temporarily employed from the country during the running of the fish, and are now discharged (Bunce 1861). Above and beyond the simple fact that the Spanish Indians living in these Cuban fishing communities were intermarried with the Spanish fishermen and sailors living there, and had no direct connection to the Seminole tribe, numerous accounts further confirm that their culture was more Hispanic than Indian, and more maritime than terrestrial. As noted in a letter arguing against their removal with the Seminoles, Judge Augustus Steele asserted that [a]t all the fisheries along the coast, from Jupiter on the east to Tampa on the west, there are a number of Indians and half-bloods who owe no allegiance to, and of whom none is claimed by, the Seminoles, though descended from them. They were born in the different ranchos or fishing places, mostly speak Spanish, and in some instances have been baptized in Havana. They were Spanish fishermen, under the Spanish government of Florida. They are not recognized by the Seminoles ... they are entirely identified by habit, occupation, and intermarriage with people of another nation of different pursuits and modes of life, and incapable of supporting themselves by ordinary Indian means. By driving them from the sea you would take them from their only resource, and place them in absolute want, without aid from some unprovided source. To show further that these persons have not been considered as Indians, by the character of their employment, two of those in Captain Buner’s [Bunce] service are registered as seamen on a vessel roll of equipage in the customhouse at Key West, and another is enrolled among my revenue crew, and is a first rate seaman, having followed the sea from a boy (Steele 1835). A later petition by the fishermen left behind after their mixed-blood wives and children were forcibly removed west with the Seminoles made a similar assertion in 1838 (transcribed in Covington [1954]): Your memorialists respectfully urge that neither they nor their families have lived within the Indian boundaries, nor have they been subject to the Indian laws, that their associations––mode of life are all actually different from those which characterize that people. That their families are incaple (sic) of gaining a subsistence by the means usual among the Indians, and that their removal to a strange country when their long accustomed occupations and only means of support could not be pursued must inevitably subject them to hopeless destitution and wretchedness. Based on these and other accounts, it is clear that by the early 19th century, the Spanish Indians of Southwest Florida were indeed a creole population that was fundamentally linked to the Cuban fishing industry, and that represented an ethnic and cultural blend of Spanish and Creek identities, uniquely adapted to the coastal estuaries of Florida’s lower peninsular Gulf Coast. Neither fully Spanish nor fully Indian, these Spanish Indians were the result of a decadeslong process of creolization, and formed an entirely new ethnic group forged during the European colonial era. Moreover, even beyond the Spanish and Indian connection, there is also at least some evidence for an African presence in these Cuban fishing communities. The same baptismal books that contain records of Spanish Indian baptisms also include baptisms for the children of enslaved Africans owned by Cuban fishermen. Among the records discovered to date are not only the 1824 and 1826 baptisms of two children of slaves John E. Worth—Creolization in Southwest Florida owned by José María Caldez and his wife Maria de Regla González, but also the 1836 baptism and simultaneous manumission of the infant son of a free Cuban pardo named Martín Gerdez and a parda slave named María de los Dolores Caldez, owned by José María Caldez and described as a native of “Cayo Tio Zespez,” or Useppa Island (Cortés y Salas 1824[2]:105, 1826[2]:297, 1836[3]:568). At least one of Caldez’s part-African slaves is therefore known to have been born at the Useppa rancho during the 1810s or 1820s, making it at least possible that there were individuals of African ancestry, as well as Spanish and Indian, residing at this and perhaps other fisheries. In addition, during the American period rumors abounded that the Cuban ranchos were a haven for runaway African slaves and a potential avenue for escape via ship to Havana, and that maroon communities of fugitive slaves were being armed and supplied from Spanish sources (Humphreys 1825; Boyd 1958). Though no individuals of African ancestry are specifically singled out in the available documentary descriptions of these ranchos from the American period, there seems little doubt that there was at least some African presence and interaction during the early 19th century. Archaeology and the Ranchos From an archaeological perspective, the preserved physical traces of these Cuban fishing ranchos would seem to represent a significant opportunity to explore the material manifestations of creolization, especially since these coastal Spanish Indian communities were geographically isolated from surrounding populations, though clearly enmeshed within an active network of maritime and terrestrial trade and communication that extended from Cuba to the interior southeastern United States. Contemporary descriptions of the ranchos during the American period provide some detail of their physical appearance, as well as their subsistence and provisions. In 1824, James McIntosh, captain of the U.S. schooner Terrier, described the Punta Rasa fishery as quoted in Dodd (1947:247): A considerable part of the key is cleared, and under fine culture of corn, pumpions, and melons. There are nine neat well thatched houses, with an extensive shed 151 for drying fish, and a store house for their salt and provisions. Ten or fifteen bushels of salt, a small cask containing a few gallons of molasses, with a little salt provisions, were all I could discover they had. The following year, Isaac Clark visited the Charlotte Harbor vicinity, noting that “there are three fisheries in the Harbour, they are established on the Keys near the Entrance in all forty three Spaniards, and several Indians, They live in Huts Constructed of Palmetto Similar to the Indians, they appear to be industrious and attend to their Fishery alone” (Clark 1825). Years later, William Whitehead provided the following detail on the Cayo Pelau rancho, which he visited in 1831: The houses were 12 in number exclusive of 2 spacious stone houses and all deserted. Not a living soul (save the dogs—and it is doubted that they have souls) was to be seen, but the absence of canoes and nets accounted for the disappearance of the inhabitants. Their dwellings were all of Palmetto and most of them of tolerable size (not a very definite expression by the by—but my saying they were) about fifteen feet square (well render it more so). They reminded me of Ichabod Crane’s School House, to enter which every facility was afforded, but which it was impossible to leave. Such being the nature of the fastenings of their doors I took the liberty of “prying” into one of them. A few stakes driven into the ground, with cross pieces for their beds—a small loft for corn—a hanging shelf with one or two pieces of crockery and two or three small stools, compased all the furniture, and no residence that I saw at any other of the Fisheries contained more, while many of them had less (Whitehead 1832). In 1837, John Lee Williams provided additional descriptions of the Charlotte Harbor region based on previous visits he and others had made, including 1828 and 1832 (Williams 1837:61,289,294). His description of the Caldez rancho on Useppa Island is also informative: It is the seat of the Calde family. Their village consists of near twenty palmetto houses, and stands on the south west point of the Island. This Island is a high shell bank, covered with large timber. A small portion of the land is under cultivation. The inhabitants living principally on fish, turtle, and coonti; the last, they bring from the main. Here are several cocoanut trees in bearing, orange, lime, papayer, hawey, and hickok plum. They raise cuba corn, peas, mellons, &c. (Williams 1837:33). These accounts leave the impression that the Florida ranchos were relatively insubstantial from an architectural point of view (with the pos- 152 sible exception of Whitehead’s “spacious stone houses” on Cayo Pelau), and generally consisted of a small number of simple but sturdy woodand-thatch structures, described on one occasion as resembling those used by Indians. Most were residential, but a storehouse and a shed for drying fish were also noted. Apart from the sloops, schooners, and other vessels routinely anchored at the rancho communities, portable material culture items appear to have been in relatively limited supply, as highlighted by William Whitehead’s amusing experience of visiting one fishery (that of Caldez) with a knife but no fork, and another (possibly Estero Island) with a fork but no knife (Whitehead 1832). Visitors noted only stools, cots, a few pottery dishes and vessels, and a cask and presumably other containers for molasses, salt, and other provisions. Food seems to have consisted of a combination of locally grown agricultural products such as corn, peas, pumpkins, and melons, assorted fruits including coconut, orange, lime, and papaya, the Florida coontie plant from the mainland, and a range of fresh and salted fish and turtle meat. Some foods were doubtless brought in by ship; Whitehead (1832) described a breakfast presented by Caldez consisting of “a large dish of cold fish, some bread, cold potatoes and onions which, with some coffee made in a moment.” The archaeological signature of any of these rancho sites would likely be distinctive but comparatively ephemeral. What little is presently known, however, is based on limited testing at only a small number of identified sites, including Useppa Island in Pine Island Sound and Estero Island on Estero Bay (Palov 1999; Schober and Torrence 2002), and analysis of accidentally discovered human remains presumed to date to this period in Sarasota and at Indian Field adjacent to Pine Island (Luer 1989; Almy 2001). Isolated finds of artifacts likely related to the Cuban fishing industry are also common at a number of sites along the Southwest Florida coast, though more intensive investigations have yet to be undertaken at most of these sites. The sites above have all produced artifacts consistent with occupation dating to Florida’s second Spanish period (1783–1821). Excavations at what is presumed to have been the Caldez fishery on Useppa Island (8LL51) produced a broad range of artifacts dating to the late HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 46(1) 18th and early 19th centuries, including course earthenware (olive jar, El Morro ware, Rey ware, Marine ware), refined earthenware (pearlware and some whiteware and stoneware), a diversity of glass shards, glass beads, clay pipe stems, buttons, nails, a thimble, round lead bullets, a lead sinker, and several sheetlead fragments or chunks (Palov 1999:152– 165). Testing at the Estero Island site (8LL4) produced a small quantity of European ceramics from the Cuban fishing period, including course earthenwares (olive jar, El Morro ware, Rey ware, and majolica), as well as refined earthenwares (predominantly pearlware), a small number of glass beads, and a round lead bullet (Schober and Torrence 2002:100–116). The Native American burial at Indian Field (8LL39) produced only a range of personal items including a gun, gunflints, a knife, a mirror, and beads (Luer 1989). The latter were examined and found to be consistent with a late-18th- or early-19th-century date (Luer 1989:239). The Sarasota burial (8SO2617), of indeterminate non–Native American ancestry was accompanied only by coffin nails thought to date to the 19th century (Almy 2001:34–45). While relatively consistent in their blend of Hispanic and Anglo-American material culture, the artifact assemblages identified at these and other sites in the area of the Cuban fishing ranchos are nonetheless marked by the conspicuous absence of any identified traces of what would normally be considered traditional Native American material culture, most notably in the case of Creek- or Seminole-style handmade ceramics, commonly brushed during this era, which continued to be manufactured well into the 1830s (Weisman 1989:51–58,69–74,85–92,112–123). As yet, no site in the vicinity of the Cuban fishing ranchos has produced direct evidence for contemporaneous Native American–style pottery within these otherwise European ceramic assemblages, despite the fact that the majority of the inhabitants during the early 19th century can be documented to have been of either Creek or part-Creek ancestry. While more extensive excavations including sealed feature contexts may well modify this conclusion, it seems highly likely, given available evidence, that the material culture of the Spanish Indians may be largely indistinguishable from a typical Cuban or Spanish colonial assemblage from the era. John E. Worth—Creolization in Southwest Florida Archaeological evidence from the built environment is presently lacking, but this may actually be an area where distinguishing features may be discernable, especially given contemporary accounts of structures “similar to the Indians” (Clark 1825). Another area where unique markers of Spanish Indian or rancho culture may be found is in the realm of subsistence, which seems to have incorporated a blend of local and extralocal foodstuffs, including both estuarine and terrestrial resources. Data are unfortunately insufficient in these areas, but should be explored in future work. Demise and Removal Ultimately, the emergent creole identity of the Spanish Indians seems to have played an important role in their downfall and in the collapse of the entire rancho system as it existed through the mid-1830s. While from an internal perspective the creole culture of the Spanish Indians (including their non-Indian husbands) may well have been clearly defined and readily discernable, from the outside the inhabitants of these coastal rancho communities represented an ambiguous blend of ethnicities and allegiances, one that was easily exploited by antagonists in a variety of struggles that played out in peninsular Florida during the 1820s and 1830s. Almost immediately after the formal transfer of Florida from Spanish to United States control, a band of some 200 Creek Indians under William McIntosh was dispatched from Georgia in 1821 by General Andrew Jackson to conduct a raid against the African maroon community of Angola located on Tampa Bay (Brown 2005:11–14; Wasserman 2009:191–198; Baram, this volume). After capturing several hundred fugitive slaves and destroying the settlement, the raiders continued south along the coast as far as the Punta Rasa rancho, where they, failing to find the escaped slaves they were expecting, sacked this and other fisheries to the amount of some $2,000 worth of property. The Cuban fisheries survived despite the Creek slave-catching raid of 1821, but after the movement of the Seminole Indians southward into the interior of central peninsular Florida following the 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek, the coastal Spanish Indian communities ultimately became linked, unwittingly, in the ongoing struggle 153 between United States and the Seminoles. At the start of the Second Seminole War (1835–1842), a band of Seminoles under Chief Wy-ho-kee destroyed the Useppa rancho in 1836, provoking the remaining 100 Spanish Indians from throughout the Charlotte Harbor region to flee north to gather at William Bunce’s fishery on Tampa Bay (Buker 1969:256–258; Hammond 1973:374–379). Over the course of the next two years, pressure increased for the removal of these Spanish Indians along with the Seminoles; U.S. officials were inclined to see the Spanish Indians as part of the Seminole threat, and the Seminoles for their part refused to emigrate west without the Spanish Indians sheltered at Bunce’s fishery. In the end, all of the Spanish Indian wives and children (and at least a few of the Spanish husbands) were forcibly removed by ship to New Orleans, ultimately arriving in Arkansas by 1841 (Capers 1841; Sturtevant 1953:54). It was apparently in this context that the Spanish Indian Antonio took on the identity of Chakaika and went to war against the United States. When faced with the prospect of removal, Chakaika and others chose to flee south and inland to the Everglades, taking up arms against American military and civilian forces from 1839 to 1840, and effectively joining the Seminoles in their war against the United States (Sprague 1848:243–246; Sturtevant 1953; Covington 1954; Adams 1970; Wright 1986:300). As noted in retrospect in 1848: South of Pease Creek [Peace River] and Lake Okechobee, near the extreme southern point of the peninsula, was a band of Spanish Indians, under an intelligent chief, called Chekika, speaking a language peculiarly their own, a mixture of Indian and Spanish. They numbered about one hundred warriors. They took no part in the war until 1839 and ’40, when, finding themselves attacked and pursued, they took arms and resisted. This band of Indians was entirely unknown. In all the treaties that had been made and councils held by agents of the government, they had had no participation. Numbers had visited the Island of Cuba, and looked more to the Spaniards as their friends, than they did to the Americans (Sprague 1848:99–100). The identity of the previously unknown Chakaika was clarified considerably in a letter written to General William Worth a year after the Spanish Indian’s death, describing the coasts of South Florida as a place “where Indians were 154 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 46(1) employed not only as fishermen at the ranchos, but as sailors to navigate those Spanish vessels, among which were Antonio Nikeka (hanged by Col. Harney) names no doubt familiar to you” (Fitzpatrick and Wyatt 1842). This, combined with contemporary testimony that he was considered “the largest Indian in Florida,” measuring more than 6 ft. tall and more than 200 lb., makes it not only likely that he was born and raised in one of the ranchos along the coast, but that he might also have had a Spanish father or grandparent (his mother, sister, and wife were captured at the time of his death) (Sturtevant 1953:53). Regardless of his birth and upbringing, however, it was his choice to flee the ranchos in the face of forced removal that ultimately defined him as Chakaika, eventually leading to ruin. Conclusion The death of Chakaika, and the defeat and capture of his rebel band, marked the final chapter of a remarkable creole community along the Southwest Florida coast, and one that has yet to receive the scholarly attention it deserves. Though there are likely descendants of the Spanish Indians among the modern Seminoles, the culture of this maritime creole community, as well as the details of its origins and early evolution, remains to be explored in full. While this article is a only brief overview of an ongoing effort toward that end, a few generalizations are warranted here. The ethnogenesis of the Spanish Indians of Southwest Florida was neither accidental nor inevitable. The two cultures that met and intermingled alongside the region’s rich estuaries were not simply thrust together randomly by the exigencies of the European colonial era. Under British (1763–1783) and second Spanish (1783–1821) dominion, the rancho communities that served as the birthplace of Spanish Indian culture operated in near-total isolation within a depopulated southern Florida peninsula. The ranchos were located some 200 to 300 mi. by sea from the Cuban home of the Spanish fishermen, more than 150 mi. by land from the nearest Spanish settlements in northern Florida, and more than 350 mi. from the homeland of the Creek Indians in present-day Georgia and Alabama. Cuban fishermen had been attracted to Southwest Florida by the fisheries since the late 17th century, though after 1763 this was only with the assent of the Creek Indians who laid claim to much of the unoccupied western Florida peninsula. The Creek Indians who met them there were attracted by the promise of alliance building and also by gifts and trade. This trade also provided vital supplies for the Cuban fishermen and was a pivotal factor enabling their lengthy stays in Southwest Florida. Both groups were there voluntarily, attracted by the lure of commercial and political benefits manifested by mutual interaction and balanced engagement. These were not unwilling alliances of convenience, but deliberate associations by choice. Perhaps in large part because of their isolation from the rest of the colonial world, first seasonally and later year-round, the inhabitants of these rancho communities ultimately seem to have formed their own unique culture. While undoubtedly drawing on different cultural traditions with roots in Spain, the Canary Islands, Cuba, Mexico, the southeastern United States, and perhaps other areas (including Africa), the Spanish Indian culture that was forged in late-colonial Southwest Florida was surely a distinctive product of those particular rancho communities, specific to that time and place. Neither group held definitive sway over the other, and their meeting place was effectively “neutral” ground. The Spanish fishermen based in Regla, Cuba, had already adapted their own fishing techniques to the particular environment of the Florida estuaries, and the Creeks had no prior experience in maritime fishing at all. Both groups were living in an environment for which they had no direct precedent and were eating foods and using tools and materials that were alien to their own cultural traditions. The social environment was similarly novel to both groups, not just because of the particular ethnic mix of the rancho communities, but also due to the extreme geographic isolation from any other significant resident populations. Over the course of perhaps three or more generations between the 1760s and the 1830s, Southwest Florida’s coastal fishing communities developed something more than just a hybrid of Spanish and Indian. What emerged was a new culture, a new identity, one born within the turbulent setting of the colonial era, but not strictly defined by the relationships of dominance normally presumed to be characteristic of colonialism. 155 John E. Worth—Creolization in Southwest Florida In this sense, Southwest Florida’s Spanish Indians represent a distinctive example of the process of creolization, highlighting the extent to which voluntary associations in unfamiliar and isolated territory could lead to the ethnogenesis of creole cultures with only incomplete resemblance to either or both parent cultures. Not all interactions between members of indigenous and colonizing populations were characterized by additive or subtractive cultural processes such as acculturation, transculturation, or deculturation; the colonial frontier also served as a cradle for entirely new cultural formations and identities that were more than simply the sum of their parts. Perhaps this should not be surprising, given that it is the very nature of culture to adapt and innovate under changing conditions. Nevertheless, the example of creolization in Southwest Florida provides an important laboratory for examining the nuances of ethnogenesis when representatives of two markedly different cultures came together on remote, neutral ground and became one. References Adams, George R. 1970 The Caloosahatchee Massacre: Its Significance in the Second Seminole War. Florida Historical Quarterly 48(4):368–380. Almy, Maranda M. 2001 The Cuban Fishing Ranchos of Southwest Florida, 1600s–1850s. Bachelor’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, Gainesville. Alonso, Pedro 1760 Letter to the Spanish Crown, 9 July. Legajo 1210, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Boyd, Mark F. 1958 Horatio S. Dexter and Events Leading to the Treaty of Moultrie Creek with the Seminole Indians. Florida Anthropologist 11(3):65–95. Boyd, Mark F., and José Navarro Latorre 1953 Spanish Interest in British Florida, and in the Progress of the American Revolution: (I) Relations with the Spanish Faction of the Creek Indians. Florida Historical Quarterly 32(2):92–130. Brown, Canter, Jr. 2005 Tales of Angola: Free Blacks, Red Stick Creeks, and International Intrigue in Spanish Southwest Florida, 1812–1821. In Go Sound the Trumpet: Selections in Florida’s African American History, D. H. Jackson, Jr., and C. Brown, Jr., editors, pp. 5–21. University of Tampa Press, Tampa, FL. Buker, George E. 1969 Lieutenant Levin M. Powell, U.S.N., Pioneer of Riverine Warfare. Florida Historical Quarterly 47(3):253–275. Bunce, William 1861 Letter to General Wiley Thompson, 9 January 1835. In American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, for the First and Second Sessions of the Twenty-Fourth Congress, Commencing January 12, 1836, and Ending February 25, 1837, Volume VI: Military Affairs, A. Dickins and J. W. Forney, editors, pp. 484–485. Gales & Seaton, Washington, DC. Calloway, Colin G. 1995 The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. Capers, LeGrand G. 1841 Muster Roll of Florida Indians to Emigrate West of the Mississippi River, under the Direction of Maj. W. G. Belknap, U.S.A. in the Month of March 1841. Microfilm, M234, Roll 291, Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824–1881, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. Clark, Isaac 1825 Letter to the Quartermaster General, 20 February. In The Territorial Papers of the United States, Vol. 23, The Territory of Florida, 1824–1828, C. E. Carter, editor, pp. 181–183. U.S. Department of State, Washington, DC. Cortés y Salas, Joseph María 1807–1836 Bautismos de Pardos y Morenos, Libros 1–3 (Baptisms of pardos and morenos, books 1–3). Archivo Parroquial del Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Regla, Regla, Cuba. Covington, James W. 1954 A Petition from Some Latin-American Fishermen; 1838. Tequesta 14:61–65. 1959 Trade Relations Between Southwestern Florida and Cuba, 1660–1840. Florida Historical Quarterly 38(2):114–128. Cusick, James G. 2000 Creolization and the Borderlands. Historical Archaeology 34(3):46–55. Deagan, Kathleen A. 1973 Mestizaje in Colonial St. Augustine. Ethnohistory 20(1):55–65. 1983 Spanish St. Augustine: The Archaeology of a Colonial Creole Community. Academic Press, New York, NY. 1996 Colonial Transformation: Euro-American Cultural Genesis in the Early Spanish-American Colonies. Journal of Anthropological Research 52(2):135–160. 156 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 46(1) 1998 Transculturation and Spanish American Ethnogenesis: The Archaeological Legacy of the Quincentenary. In Studies in Culture Contact: Interaction, Culture Change, and Archaeology, J. G. Cusick, editor, pp. 23–43. Southern Illinois University, Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Paper No. 25. Carbondale. de 1775a Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, 4 May. Legajo 1220, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1775bLetter to the Intendente General of Havana, 1 June. Legajo 1220, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1776a Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, 11 April. Legajo 1221, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1776bLetter to Joseph de Gálvez, 9 October. Legajo 1222, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1777a Letter to Joseph de Gálvez, 6 May. Legajo 1222, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1777bLetter to Joseph de Gálvez, 16 May. Legajo 1222, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Aguilar, Juan 1810a Letter to the Governor of Havana, 10 November. Legajo 1598, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1810bLetter to the Governor of Havana, 11 December. Legajo 1598, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. de Arango, Joseph 1796a Expenses Made for Gifts to Indians in the Year 1796. Legajo 1857, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1796bExpenses for Purchases of Salt and Salaries for Customs and Military Officials Stationed at Cayo de Sal for the Year 1796. Legajo 1857, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1797a Expenses Made for Gifts to Indians in the Year 1797. Legajo 1858, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1797bExpenses for Purchases of Salt and Salaries for Customs and Military Officials Stationed at Cayo de Sal for the Year 1797. Legajo 1858, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1798a Expenses Made for Gifts to Indians in the Year 1798. Legajo 1859, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1798bExpenses for Purchases of Salt and Salaries for Customs and Military Officials Stationed at Cayo de Sal for the Year 1798. Legajo 1859, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. de Arriaga, Julian 1771 Letter to the Governor of Havana, 21 October 21. Legajo 1211, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. de Cagigal, Juan Manuel 1819 Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, 20 December. Legajo 1935, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. de Cárdenas, Alfonso María 1786 Letter to the Governor of Havana, 30 December. Legajo 1397, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1787 Letter to the Governor of Havana, 3 January. Legajo 1397, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. de Fondesviela y Ondeano, Felipe 1773 Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, 28 March. Legajo 1164, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1774 Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, 1 April. Legajo 1218, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. de la Hoz, Juan Joseph 1803 Letter to the Governor of Havana, 22 December. Legajo 1590, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. de las Casas, Luis 1793 Letter to the Spanish Crown, 1 February. Document No. 4, Legajo 14, Papeles de Estado, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. de León, José María 1818a Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, 8 January. Legajo 1884, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1818bLetter to the Intendente General of Havana, 24 July. Legajo 1884, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1819a Letter to Intendente General of Havana, 17 July. Legajo 1885, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1819bLetter to the Intendente General of Havana, 9 August. Legajo 1885, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1819c Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, 2 November. Legajo 1935, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1819dLetter to the Intendente General of Havana, 22 December. Legajo 1935, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1819e Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, Regarding Items Requested by the Chiefs of the Chocochates and Tasquicalques, 29 December. Legajo 1935, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1819f Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, Regarding Items Requested by the Chiefs of the Simanoles and Tamasalques, 29 December. Legajo 1935, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1820a Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, 10 January. Legajo 1935, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1820bLetter to the Intendente General of Havana, 26 January. Legajo 1935, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 157 John E. Worth—Creolization in Southwest Florida 1820c Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, 28 January. Legajo 1935, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1820dLetter to the Intendente General of Havana, 24 November. Legajo 1936, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1820e Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, Regarding Items Requested by Chief Yaja Tastonaque, 19 December. Legajo 1936, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1820f Letter to the Intendente General of Havana, Regarding Items Requested by the Chiefs of the Nuevos Uchises and Tamasalques, 19 December. Legajo 1936, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1821 Request to Reimburse Expenses Incurred with the Visit to Havana of Twenty-two Indians from the Coast of Tampa in Two Fishing Vessels, 7 November. Document No. 110, Intendencia General de Hacienda 1125, Archivo Nacional de Cuba, Havana, Cuba. 1823 Request to Reimburse Expenses Incurred with the Visit to Havana of Twenty-two Indians from the Coast of Tampa in Two Fishing Vessels, 2 December. Document No. 18, Intendencia General de Hacienda 232, Archivo Nacional de Cuba, Havana, Cuba. del Río, Felipe 1789a List of Supplies Delivered to José Bermúdez for Gifts and Sustenance to Eleven Indians Visiting Havana from the Coast of Tampa, 26 January. Legajo 2144, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1789bList of Supplies Delivered to José Bermúdez for Gifts and Sustenance to Twenty-eight Indians Visiting Havana from Cayo Antoche, 6 February. Legajo 2144, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1789c List of Supplies Delivered to José Bermúdez for Gifts and Sustenance to Twenty-four Indians Visiting Havana from the Coast of Tampa, 27 June. Legajo 2144, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. de Urriza, Juan Ignacio 1782 Letter to the Governor of Havana, 16 February. Legajo 1307, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. de Zunzunegui, Juan Bautista 1800 Table of the Warehouse Accounts for Havana for the Year 1800. Legajo 2150, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1801 Table of the Warehouse Accounts for Havana for the Year 1801. Legajo 2150, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1802 Defense against Charge of Having Substituted Vermillion for Red Lead in Gifts to Uchise Indians Visiting Havana in January, 1792. Legajo 2145, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Dickins, Asbury, and John W. Forney (editors) 1860 American State Papers: Documents of the Congress of the United States in Relation to the Public Lands, from the First Session of the Twenty-First to the First Session of the Twenty-Third Congress, Commencing December 1, 1828, and Ending April 11, 1834, Volume VI: Public Lands. Gales & Seaton, Washington, DC. Dodd, Dorothy 1947 Captain Bunce’s Tampa Bay Fisheries. Florida Historical Quarterly 25(3):246–256. Eligio de la Puente, Juan Joseph 1777a Letter to the Governor of Havana, 2 July. Legajo 1290, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1777bReport on the Friendship and Loyalty of the Uchise and Talapuze Nations, 28 December. Legajo 1290, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Ewen, Charles R. 1991 From Spaniard to Creole: The Archaeology of Cultural Formation at Puerto Real, Haiti. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa. 2000 From Colonist to Creole: Archaeological Patterns of Spanish Colonization in the New World. Historical Archaeology 34(3):36–45. Feliu, Melchor 1762 Letter to the Spanish Crown, 25 March. Legajo 2585, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Ferguson, Leland 1992 Uncommon Ground: Archaeology and Early African America, 1650–1800. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC. 2000 Introduction. Historical Archaeology 34(3):5–9. Fernández, Julian 1821 Letter to the Governor of Havana, 30 July. Legajo 1969A, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Fitzpatrick, Robert, and William Wyatt 1842 Letter to William J. Worth, 9 July. In The Territorial Papers of the United States, Vol. 26, The Territory of Florida, 1839–1845, C. E. Carter, editor, p. 509. Department of State, Washington, DC. Galeano, Pedro Rafael 1799 Summary of Purchases of Supplies for the Fort of El Principe in Havana for the Year of 1792, 20 July. Legajo 2145, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Gálvez, Joseph de 1783 Royal Order to the Intendente General of Havana Approving the Expenses Made with Visiting Uchise Indians in Order to Promote Commerce, 24 May. Document No. 5, Reales Cédulas y Ordenes 19, Archivo Nacional de Cuba, Havana, Cuba. 158 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 46(1) Gold, Robert L. 1964 The Settlement of the East Florida Spaniards in Cuba, 1763–1766. Florida Historical Quarterly 42(3):216–231. 1969 Borderlands Empires in Transition: The Triple-Nation Transfer of Florida. Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale. Gómez Rombaud, Rafael 1805a Letter to Miguel Cayetano Soler, 6 February. Document No. 73, Floridas 21, Archivo Nacional de Cuba, Havana, Cuba. 1805b Letter to the Governor of Havana, 13 August. Legajo 1592B, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1805c Letter to the Governor of Havana, 23 December. Legajo 1592B, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Gundaker, Grey 2000 Discussion: Creolization, Complexity, and Time. Historical Archaeology 34(3):124–133. Hammond, E. Ashby 1973 The Spanish Fisheries of Charlotte Harbor. Florida Historical Quarterly 51(4):355–380. Hann, John H. 1991 Missions to the Calusa. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Humphreys, Gad 1825 Letter to the Secretary of War, 2 March. In The Territorial Papers of the United States, Vol. 23, The Territory of Florida, 1824–1828, C. E. Carter, editor, p. 202. Department of State, Washington, DC. Lightfoot, Kent. G., and Antoinette Martinez 1995 Frontiers and Boundaries in Archaeological Perspective. Annual Review of Anthropology 24:471–492. Loren, Diana DiPaolo 2000 The Intersections of Colonial Policy and Colonial Practice: Creolization on the Eighteenth-Century Louisiana/Texas Frontier. Historical Archaeology 34(3):85–98. Luer, George M. 1989 A Seminole Burial on Indian Field (8LL39), Lee County, Southwestern Florida. Florida Anthropologist 42(3):237–240. McEwan, Bonnie G., and Jeffrey M. Mitchem 1984 Indian and European Acculturation in the Eastern United States as a Result of Trade. North American Archaeologist 5(4):271–285. Monroe County Clerk of the Circuit Court 1833 Deed of Sale of Key Sespas [Useppa Island] by Joseph Caldes to Joseph Ximénez, 23 January. Deed Book A, Monroe County Clerk of the Circuit Court, Key West, FL. Mouer, Daniel 1993 Chesapeake Creoles: The Creation of Folk Culture in Colonial Virginia. In The Archaeology of 17th-Century Virginia, T. Reinhart and D. Pogue, editors, pp. 105–166. Archaeological Society of Virginia, Special Publication, No. 30. Charlottesville. Mullins, Paul R., and Robert Paynter 2000 Representing Colonizers: An Archaeology of Creolization, Ethnogenesis, and Indigenous Material Culture among the Haida. Historical Archaeology 34(3):73–84. Navarro, Diego José 1779 Letter to Joseph de Gálvez, 22 December. Legajo 1291, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1780 Letter to Joseph de Gálvez, 20 February. Legajo 1291, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Palov, Maria Z. 1999 Useppa’s Cuban Fishing Community. In The Archaeology of Useppa Island, W. H. Marquardt, editor, pp. 149–165. Institute of Archaeology and Paleoenvironmental Studies, Monograph No. 3. Gainesville, FL. Pamanes, Joseph 1780 Record of the Purchase of Salted Fish for the Royal Warehouse in Havana, 19 January. Legajo 2145, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Peñalver y Cardenas, Ignacio 1769 Expenses for the Purchase of Salted Fish, 18 March. Legajo 1844, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1771 Expenses for the Purchases of Salted Fish, 8 February and 11 February. Legajo 1844, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1772 Expenses for the Purchase of Salted Fish, 19 February. Legajo 1845, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1773 Expenses for the Purchases of Salted Fish, 16 March and 18 March. Legajo 1845, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1774a Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1774. Legajo 1845, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1774bExpenses for the Purchases of Salted Fish, 2 March and 23 March. Legajo 1845, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1775 Expenses for the Purchase of Salted Fish, 18 April. Legajo 1845, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1776 Expenses for the Purchase of Salted Fish, 28 March. Legajo 1846, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1777a Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1777. Legajo 1847, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 159 John E. Worth—Creolization in Southwest Florida 1777bExpenses for the Purchase of Salted Fish, 6 February. Legajo 1847, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1778a Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1778. Legajo 1848, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1778bExpenses for the Purchase of Salted Fish, 29 January. Legajo 1848, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1779a Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1779. Legajo 1848, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1779bExpenses for the Purchase of Salted Fish, 10 February. Legajo 1848, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1780 Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1780. Legajo 1849, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1781 Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1781. Legajo 1849, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1782 Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1782. Legajo 1849, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1783 Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1783. Legajo 1850, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1785 Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1785. Legajo 1850, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1786 Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1786. Legajo 1851, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1787a Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1787. Legajo 1852, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1787bExpenses for the Purchase of Salted Fish, 22 December. Legajo 1852, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1788 Expenses for the Purchase of Salted Fish, 16 February. Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1789 Expenses for Purchases of Salt for the Year 1789. Legajo 1854, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1791 Salary Expenses for Customs and Military Officials Stationed at Cayo de Sal for the Year 1791. Legajo 1855, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1792 Salary Expenses for Customs and Military Officials Stationed at Cayo de Sal for the Year 1792. Legajo 1855, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1793a Expenses Made for Gifts to Indians in the Year 1793. Legajo 1855, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1793bExpenses for Purchases of Salt and Salaries for Customs and Military Officials Stationed at Cayo de Sal for the Year 1793. Legajo 1856, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1794 Expenses for Purchases of Salt and Salaries for Customs and Military Officials Stationed at Cayo de Sal for the Year 1794. Legajo 1856, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1795 Expenses for Purchases of Salt and Salaries for Customs and Military Officials Stationed at Cayo de Sal for the Year 1795. Legajo 1857, Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Peters, Thelma (editor) 1965 William Adee Whitehead’s Reminiscences of Key West. Tequesta 25:3–42. Quimby, George I., and Alexander Spoehr 1951 Acculturation and Material Culture. Fieldiana Anthropology 36(6):107–147. Ramírez, Alexandro 1816a Letter to the Governor of Havana, 22 August. Legajo 1882, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1816bLetter to the Governor of Havana, 29 August. Legajo 1882, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1816c Letter to the Governor of Havana, 11 November. Legajo 1882, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1816d Letter to the Governor of Havana, 20 November. Legajo 1882, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1816e Letter to the Governor of Havana, 23 December. Legajo 1882, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1818 Letter to the Governor of Havana, 20 February. Legajo 1884, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1819a Letter to the Governor of Havana, 25 February. Legajo 1885, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1819bLetter to the Governor of Havana, 13 July. Legajo 1885, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1820a Letter to the Governor of Havana, 29 August. Legajo 1936, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1820bLetter to the Governor of Havana, 28 November. Legajo 1936, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1820c Letter to the Governor of Havana, 2 December. Legajo 1936, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1821a Letter to the Governor of Havana, 16 January. Legajo 1936, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. 1821bLetter to the Governor of Havana. 26 January. Legajo 1936, Papeles Procedentes de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. Redfield, Robert, Ralph Linton, and Melville J. Herskovits 1936 Memorandum for the Study of Acculturation. American Anthropologist 38(1):149–152. 160 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 46(1) Schober, Theresa M., and Corbett McP. Torrence 2002 Archaeological Investigations and Topographic Mapping of the Estero Island Site (8LL4), Lee County, Florida. Report to Town of Fort Myers Beach, Fort Myers, FL, and Division of Historical Resources, Florida Department of State, Tallahassee, from Florida Gulf Coast University, Cultural Resource Management Program, Fort Myers. Sprague, John T. 1848 The Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War. D. Appleton & Company, Philadelphia, PA. Steele, Augustus 1835 Letter to General Wiley Thompson, 10 January. In American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, for the First and Second Sessions of the Twenty-fourth Congress,Commencing January 12, 1836, and Ending February 25, 1837, Volume VI: Military Affairs, A. Dickins and J. W. Forney, editors, p. 484. Gales & Seaton, Washington, DC. Sturtevant, William C. 1953 Chakaika and the “Spanish Indians.” Tequesta 13:35–73. 1971 Creek into Seminole. In North American Indians in Historical Perspective, E. B. Leacock and N. O. Lurie, editors, pp. 92–128. Random House, New York, NY. Voss, Barbara L. 2005 From Casta to Californio: Social Identity and the Archaeology of Culture Contact. American Anthropologist 107(3):461–474. Wasserman, Adam 2009 A People’s History of Florida 1513–1876: How Africans, Seminoles, Women, and Lower Class Whites Shaped the Sunshine State. Adam Wasserman, Sarasota, FL. Webster, Jane 2001 Creolizing the Roman Provinces. American Journal of Archaeology 105(2):209–225. Weisman, Brent Richards 1989 Like Beads on a String: A Culture History of the Seminole Indians in North Peninsular Florida. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa. Whitehead, William A. 1832 Memorandums of Peregrinations by Land and Water–– Vol. 2nd., from July 1830 to May 1832. Manuscript, Monroe County Public Library, Key West, FL. Williams, John Lee 1837 The Territory of Florida: or Sketches of the Topography, Civil and Natural History, of the Country, the Climate, and the Indian Tribes, from the First Discovery to the Present Time. A. T. Goodrich, New York, NY. Worth, John E. 2003 The Evacuation of South Florida, 1704–1760. Paper presented at the 60th Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Charlotte, NC. 2004 A History of Southeastern Indians in Cuba, 1513–1823. Paper presented at the 61st Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, St. Louis, MO. 2009 Razing Florida: The Indian Slave Trade and the Devastation of Spanish Florida, 1659–1715. In Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South, Robbie Ethridge and Sheri ShuckHall, editors, pp. 295–311. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. Wright, J. Leitch, Jr. 1986 Creeks & Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. John E. Worth Department of Anthropology University of West Florida 11000 University Parkway, Pensacola, FL 32514