Indigenous Architecture of Ecuador

advertisement

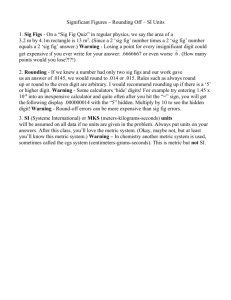

llppiwroHintwifl INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURE OF ECUADOR By Richard Johnson O utsiders may view native a r c h i t e c t u r e as backward or primitive, but over the centuries, i t has answered human needs of survival, often achieving a r e markable balance with the natural surroundings. Today, throughout t h e T h i r d World, newer 'modern,' 'Western,' 'developed' architecture i s rapidly replacing t r a d i t o n a l housing. However, such 'imported' a r c h i t e c ture is often t o t a l l y inadequate t o t h e needs of i t s u s e r s — frequently downright unsuitable to local conditions. 'Underdeveloped' and ' d e v e l oped' are value judgements. Applied t o architecture, they imply some sort of spurious ideal model. This has led t o structures being b u i l t t h a t are not m e r e l y ugly, but p h y s i c a l l y , economically, socially, and in every other sense i l l s u i t e d t o an a r e a . Before imposing f o r e i g n a r c h i t e c t u r a l concepts on Third World countries, we should study indigenous values. Alas, few a r e the p r o f e s s i o n a l 22 architects able to appreciate and i n c o r p o r a t e the l e s s o n s l e a r n e d over centuries by native artisans. A t r i p through Ecuador reveals a v a r i e t y of native housing styles and b u i l d i n g technique s i n the country's three d i s t i n c t climatic zones. My research of Ecuadorian housing concentrated on two major styles — the thatched hut of the high Andes and lowland housing typical of the upper Amazon, This a r t i c l e is about the former. In Ecuador today, land reform, o i l discoveries and modern technology a r e some of t h e f o r c e s uprooting rural populations. Ecuador i s undergoing social upheaval. In the midst of this, t r a d i t i o n al housing styles are giving way to concrete block houses with corrugated t i n or p l a s t i c roofs. Concrete b l o c k s are not o n l y c o s t l y , but o f f e r none of the advantages of t h a t c h . Nonetheless, the 1974 Ecuadorian census r e v e a l e d t h a t the t h a t c h e d h ut remains the most common form of housing. I narrowed my study t o PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHOR Chimborazo Province where f u l l y 53 p e r c e n t of t h e h o u s i n g is thatched, a fact a t t r i b u t a b l e to the large numbers of Indians who l i v e t h e r e and own t h e i r own houses. In o t h e r provinces, thatched housing i s more c l e a r ly on the way out, and even i n Chimborazo few new thatched homes are b e i n g b u i l t . The b i a s a g a i n s t t h a t c h e d s t r u c t u r e s i s more o b vious i n the census i t s e l f . Every b r i c k and c o n c r e t e s t r u c t u r e i s l i s t e d , but a l l thatched huts and o t h e r indigenous housing which make up over h a l f of Ecuadorian d w e l l i n g s are grouped t o g e t h e r under the heading of 'other.' Since architecture i s a central expression of l i f e s t y l e , I made an e f f o r t t o l e a r n as much as p o s s i b l e about t h e p e o p l e , t h e i r history, land and culture, Several centuries ago, groups of f i e r c e I n d i a n s l i v e d i n t h i s r e g i o n — t h e Cachas, Chambos, C u b i j i e s , P e n i p e s , Riobambas. Together they formed the Puruhauye n a t i o n , which, f o r a t i m e , s u c - c e s s f u l l y r e s i s t e d Incan expansion. Eventually, they were overcome, p a r t i a l l y r e s e t t l e d and pacified. Following the Conquest, h a r s h t r e a t m e n t by t h e Spanish l a i d the foundation for a d i s t r u s t of outsiders that s t i l l s prevails. Even so, I found t h i s a t t i t u d e easily overcome, and I was treated with great warmth and hospitality. 1 l i v e d i n El Socorro (2,800 meters above s e a l e v e l ) , a small settlement northeast of Riobamba. This i s a lovely volcanic area, with Andean valleys running n o r t h and south. The a l t i t u d e fluctuates between 2,500 to 4,000 meters a s l . Barren, windswept and eroded h i l l s contrast with a beaut i f u l patchwork of green, c u l t i vated plots. The land supports a r e l a t i v e l y high population density — 22.52 people p e r square m i l e compared to 9.36 nationwide. Temperatures range between a winter low of 38J5°F to a summer high of 71.2°F (4-21°C). Prevailing A l i sio Winds blow from the northeast during the coldest months of Jul y and August. R a i n f a l l averages some 40 cm (16 inches) per year. Forty-tv^o percent of the popul a t i o n of Chimborazo Province i s under 14 y e a r s of age (1972). I l l i t e r a c y stands at 40 percent, and e d u c a t i o n beyond t h e s i x t h grade i s g e n e r a l l y u n a v a i l a b l e . Rural l i f e i s hard in El Socorro and isolating. The national newspaper El Comercio conducted a survey in 1973. I t reported that i n Chimborazo P r o v i n c e , some of the people believed that 'patria' (Spanish word meaning 'homeland') was the name of a local bus l i n e . Many thought that the residents of Guayaquil were f o r e i g n e r s , t h a t B o l i v a r discovered America, and that they were poor because 'God wanted i t that way.' Comments about Andean Indians, especially with respect t o t h e i r i n t e l l e c t u a l capacity, are not always kind. But the inhabitants of these upland valleys are very skilled artisans. They have, f u r t h e r m o r e , adapted t o one t h e w o r l d ' s h a r s h e s t environments — an environment poor in basic foods t u f f s . They have m i r a c u l o u s l y learned to survive a t high a l t i tudes on subsistance agriculture. Lack of water, the a l t i t u d e and eroded s o i l a l l contribute t o what t h e OAS d e s c r i b e d as Ecuador's having the lowest level of n u t r i t i o n i n South America. In El Soccoro the diet consists LOCATION OF Ecuadorian housing. w ®® 11® W 1 ecuador 1 ® JIB v ' ^ / •luEl W* Profile X8J 23 mainly of mote, large corn usually b o i l e d , t o s t a d o , f r i e d corn, habas, a l a r g e form of bean, capuli", a kind of l o c a l c h e r r y , yucho, a c e r e a l - l i k e m i x t u r e of corn flour, morocho. ground corn with milk, chawarmishki, a drink e x t r a c t e d from t h e b l a c k cabuya (Agave americano). These people can r a r e l y a f f o r d meat, perhaps once a month. Their diet averages out a t an i n s u f f i c i e n t 1,700 c a l o r i e s p e r day. According t o t h e OAS, such a d i e t poses a serious health threat, made worse by an almost t o t a l lack of medical f a c i l i t i e s i n the p r o v i n c e (one doctor for every t e n thousand inhabitants). The Indians of El Socorro can produce enough food f o r an a d e quate d i e t . The t r o u b l e s t a r t s when basic foodstuffs are sold to buy concrete block, t i n roofing, r a d i o s , and o t h e r f r i v o l o u s Western commodities. This i s what i s happening throughout the Andes. Seduced by the notion that f o r e i g n i s b e t t e r and t o escape t h e s t i g m a of b e i n g ' i n d i o , ' highland I n d i a n s a r e abandoning t h e i r old b a r t e r system for a money economy. T oday in El Socorro, and other areas where thatched housing i s found, homes a r e l o c a t e d i n areas protected against the p r e v a i l i n g winds. Huts l i t e r a l l y disappear into t h e i r surroundings, and a passerby may go through an area without noticing them at a l l . Housing in El Soccoro tends to be s c a t t e r e d . Married c h i l d e r n b u i l d homes n e a r t h e i r p a r e n t s , selecting a protected clearing set back from ravines and the danger of flash floods. Houses are b u i l t facing away from the prevailing Alisio winds that sweep in from the northeast during the coldest months, bringing, i t i s believed, bad s p i r i t s and sickness. A noteworthy feature of thatched houses i s t h e i r aerodynamic shape — a s l i g h t l y inward curving roof — which allows them to withstand the full force of the p r e v a i l i n g winds. Finally, in an area where earthquakes a r e not uncommon, t h e flexible thatched house is uniquely earthquake resistant . Concrete s t r u c t u r e s are apt t o crumble, k i l l i n g the inhabitants. All the building materials for a thatched house are found l o c a l ly, and they are few. The economic advantage of t h i s i s obvious. These materials are: Sig sig grass (Cortaderia s a l loara), also known as pa.ja brava, a long-bladed, shallow r o o t e d grass found far from construction s i t e s near the banks of rivers and l a k e s . I t i s a l s o used t o feed stock. U n f o r t u n a t e l y, s i g s i g grass i s becoming scarce because of lack of water and over-grazing. Sig sig is basically impervious t o water. Unlike o t h e r b u i l d i n g m a t e r i a l s , the whole p l a n t i s u t i l i z e d , i t does not r e q u i r e drying and can be used immediatel y . Moreover, many s i g s i g a c t u a l l y sprout in the spring rains, t h e i r roots finding sustenance in windblown earth which lodges in the thatch. Cabuya plant (Fulcrea andina), a c a c t u s - l i k e p l a n t t h a t grows everywhere, the t w o - m e t e r - l o n g l e a v e s of which are used t o t i e the s i g s i g g r a s s . The stem of ABOVE: Lemattfh and runawasi homes. Note d i f f e r e n t r o o f t o p s . LEFT: Man w i t h thatching needLe and hoz. the cabuya, c a l l e d chahuarquero, often reaches a height of almost four m e t e r s . Ten c e n t i m e t e r s (four inches) i n d i a m e t e r , and similar to bamboo, i t i s used as a beam in thatched huts. Chahuarquero i s c u t one month befor e construction t o allow for drying. Carrizo (Chosquea scandena)is a bamboo-like plant t h a t grows close t o the water. The very strong and very flexible stem i s also s u i t a b l e f o r making b a s k e t s and flutes. I t grows 3-4 meters high and must be d r i e d for s e v e r a l weeks. Totora (Thyfa l a t i f o l i a ) . This long-bladed plant grows in swampy areas and lakes. The dried plant i s woven i n t o bed mats. The leaves a l s o serve as c a t t l e fodder. Cangagua rock i s a l i g h t weight, y e l l o w i s h , porous rock found in the fields. I t i s easily worked and seen everywhere in hut foundations and fireplaces. A properly b u i l t thatched house w i l l , with minor repairs, l a s t for years. Only the thatch requires p e r i o d i c p a t c h i n g . Many of t h e houses I saw in El Socorro dated back t o the 1920s. The t h e r m a l and acoustic properties of these houses are, furthermore, remarkable and improve with each addi- tional layer of thatch. Sig sig, a tubular grass contains numerous a i r p o c k e t s , keeping a t h a t c h e d house cool in summer and warm in winter. Such homes a r e o f t e n twice as well insulated as houses in the United States. T i n r o o f s , on the o t h e r hand, have an average l i f e of 6-8 years, are deafening to live under when i t r a i n s , provide v i r t u a l l y no insulation and have the p o t e n t i a l l y lethal disadvantage of a t t r a c t ing l i g h t n i n g . Concrete b l o c k s p r o v i d e l i t t l e insulation unless f i l l e d with mica, vermiculite or some o t h e r type of i n s u l a t i o n which, even were i t a v a i l a b l e , tends t o s e t t l e and adds t o t h e overall expense. Concrete block construction i s understandable in another climate, r e g i o n and c u l t u r e . Concrete b l o c k s presuppose a r e c t a l i n e a r model with abundant timber a v a i l able for frames and beams. In the Andes, timber i s scarce, sawmills frequently unknown. The thatched home i s t h e i d e a l s t r u c t u r e for the available materials. I n a t r a d e economy, family , f r i e n d s and members of the community can be counted on t o h e l p p l a n t , h a r v e s t and b u i l d houses. Called mingas. cooperat i v e g r o u p s of 1 0 - 4 0 p e o p l e receive no money. Traditionally, they a r e compensated for t h e i r 25 labor with 'luxury' food and drink such as chicken soup, boiled potatoes, cooked grains and fried cuy (guinea pig). In addition, large quantities of Chicha, an alcoholic beverage made of corn, must be on hand t h r o u g h o u t t h e p r o j e c t . Chicha i s w i d e l y b e l i e v e d t o bestow the ' f o r c e and courage' needed for hard work. Mingas turn i n t o t r u l y s o c i a b l e e v e n t s , and depending on the resources of the host, can l a s t up t o a week. Mingas can be used for b o t h t r a d i t i o n a l and n o n - t r a d i t i o n a l construction, but t r a d i t i o n a l housing i s not only cheaper, costing only the food, i t can be b u i l t in far l e s s time. Concrete block houses require materials that must be trucked in. Also, such housing i s so expensive that i t represents a major financial drain requiring piecemeal c o n s t r u c t i o n over a period of time. A t y p i c a l minga needed for thatch construction might number 20 cutters of sig sig, six encarrizdores to t i e the thatch and one expert to finish the ridge. When the hut i s finished, a l l celebrate the event with a huasi- p i c h a y or buluhauy, r i t u a l s similar to a house-warming party. Everyone marches around the new house s e v e r a l t i m e s , t h e owner l e a d i n g the p r o c e s s i o n . Local musicians play flutes, bass drums and an occasiona l b r a s s horn. After s e v e r a l rounds, a l l e n t e r the hut (if possible) and take the owner captive. They t i e his feet, haul him up t o the r a f t e r s and t i c k l e t h e i r helpless host with straw u n t il he promises more food and especially more chicha. And then the party begins. L ike the building m a t e r i a l s , the tools required for making a t h a t c h e d hut are few and, for the most part, easily improvised from m a t e r i a l s found l o c a l l y . They include: The machete, the tool for cutting chahuarqueros and carrizo. The hoz, a f o o t - l o n g (30-cm) tool resembling a sickle for c u t t i n g s i g s i g and t o t o r a . The blade i s serrated, and the handle i s of eucalyptus wood and rags. A wooden needle, with eye hook, measuring approximately a meter in l e n g t h and two c e n t i m e t e r s i n diameter, made of eucalyptus wood, which they use to ' s t i t c h ' sig sig t o carrizo. La barra, a modern tool, a bar f l a t bladed on one end and pointed on the other, good for prying up rocks and shaping stone. In El Socorro, as elsewhere in the Andes, u n i t s of measure are d e r i v e d from the body of an average s i z e d male. While not exact, a high degree of tolerance i s not required. The vara i s the distance from the t i p of the index finger of an outstretched arm to the sternum — a p p r o x i m a t e l y 84 cm or 2.8 f t . This i s the measure used in markets to measure cloth or rope. The cuarta i s the distance from the t i p of the thumb t o the t i p of the s m a l l f i n g e r of a s t r e t c h e d out hand. The cuarta, some 15 cm (6 inches), i s used t o measure the spacing of carrizo spandrils and rows of thatching. I n El Socorro, t h a t c h e d h u t s come in four sizes. The standard (runahuasi) g e n e r a l l y belongs t o the head of the household and, as a rule, i s well b u i l t and o u t f i t ted. Larger, although r a r e , i s Cross and Sabi La plant. The sabi La is used for medicinal purposes, glu and as ridge decoration. CONSTRUCTION BY STEPS: Copete - Ridge pLanter for water protection. Made of chahuaquero or carrizo. Lined with sig sig grass and filied with fertile gray soiL and donkey manure. Previously used as a watchtower by the Puruhuayes. 1. Begin first row of thatching anacuche) at bottom, overlapping the rock. 2. Continue thatching up to workable height or rim. Construct copete [planter at rim of house) Aguja - "Y" shaped stick or wooden needle for sewing thatch Rows of overlapping sig sig thatching spaced one cuarta (6") Impervious Andean grass thatching. Two layers of thatching, up to a meter thick, is customary. Anacuche - First row of sig sig thatching overlaps base course of cangagua rack to protect it from rain, that with time would disintegrate the rock. LEFT: Woman making cabuya t w i n e . RIGHT: Hand M e a s u r e m e n t [La c u a r t a and measures a t m a r k e t [La vara]. the lematon, g e n e r a l l y housing grandparents and t h e i r extended family. Smaller huts belonging t o married children (chaquihuasi) can also be guest houses. The small e s t structures (choglia) are for s h e l t e r i n t h e f i e l d s or for animals. The standard size runahuasi in El Socorro has a floor measuring 5-6 varas (4-5 meters) by 5 varas w i t h a roof s i x v a r a s high. Built of light material and r e l a tively small, thatched huts do not r e q u i r e a subgrade foundation. One to three layers of the local cangagua rock provides more than adequate support. Mortar or mud is not needed since the stone i s e a s i l y worked i n t o a c l o s e f i t . Foundation stones are simply laid on hard e a r t h , u s i n g e i t h e r a s t r i n g or s i g h t i n g by eye along the l e n g t h t o make the s t o n e s level. Upon t h i s foundation r e s t the main structural supports — four chahuarqueros tied together a t the top forming a tripod-like s t r u c ture six varas high. These frames are raised above the foundation at either end of the house and a rope i s strung between the two to check i f they a r e l e v e l . If they a r e , they w i l l be secured permanently w i t h s a q u i p a t a rope. (No n a i l s a r e used.) Each outer pair of supports i s longer, giving pitch t o t h e r o o f and c r e a t i n g a mansard-type cone. With the poles in place, a n o t h e r l a r g e chahuaquero i s secured exactly halfway down the middle of the back w a l l . This s t a b i l i z e s the e n t i r e frame since the weight of the roof pushes not 27 \ >.;*i' fefli ABOVE: F l o o r pLan o f home w i t h s e p a r a t e cook house. OPPOSITE ABOVE: H u t i n t e r i o r . OPPOSITE BELOW: T y p i c a l c o u r t y a r d . only downward because of gravity but towards the back of the h u t because of wind pressure. S t i l l more chahuarqueros a r e needed t o complete the main frame. Then h o r i z o n t a l chahuarqueros (called cintaqueros) are t i e d around the base, one cuarta above the stone . Then from bottom t o top, at one vara intervals, more rows are added. With the cintaqueros in place, the structure takes on s t a b i l i t y . At t h i s p o i n t , a l a r g e c h a h u a r quero i s t i e d h o r i z o n t a l l y two meters above ground, at the t h i r d row of cintaqueros to support an indoor platform. Short chahuarqueros are a t t a c h ed to the frame to build a v i s o r like overhang above the entry for protection against the elements. Carrizo spandrils i n bunches of 3-4 can now be a t t a c h e d t o t h e frame, starting a t the top. The cintaqueros serve as scaffolding. The structure i s now ready for the gig sig thatching, the f i r s t row of which i s t i e d a t the base so t h a t o v e r l a p s ( s h i n g l e - l i k e ) and protects the highly absorbent cangagua rock. Thatching t r a d i t i o n a l l y employs three men inside, w i t h a n o t h e r t h r e e men working outside the frame. Those on the o u t s i d e p o s i t i o n s i g s i g one c u a r t a (approx. 20 cm or 6 in) above the previous row of thatch. A wooden needle a t t a c h e d t o a length of saquipata cord i s pushed through a sig sig plant j u s t above t h e r o o t and t h r o u g h the s p a n d r i l s . Those on t h e i n s i d e pull i n the needle, then pass i t out again under the carrizo, where the two ends of the saquipata are t i e d . I n t h i s way, working i n teams of two, the words 'sig sig, s a q u i p a t a . ' a r e chanted r h y t h mically, sometimes sounding like a song. Higher up, a smaller needle i s used t o secure the t h a t c h . The more layers, the warmer the house. An enormous amount of sig sig i s r e q u i r e d t o t h a t c h a hut — approximately 45 cubic meters for two l a y e r s . Light t a n i n c o l o r when new, the thatch darkens with time u n t i l i t blends in perfectly w i t h the landscape. T here are two ways of finish ing the top, a task performed by a s p e c i a l i s t . The s i m p l e r method i s accomplished by reversing t h e d i r e c t i o n of the t h a t c h and tying i t down with saquipata. This forms a conical ridge which w i l l shed water. The second technique i s t o b u i l d a c a r r i z o box frame on the ridge lined with sig sig. Once b u i l t , the box i s f i l l e d with about 90 kg (200 lb) of macadan (a grey, f e r t i l e soil) and donkey manure which, w i t h time, compresses t o form an effective water seal. Sabilas (aloe) are succulents planted in this s o i l t o soak up r a i n water. Sabila, also known as 'the immortal,' i s also valued for i t s medicinal and decorative q u a l i t i e s , as well as i t s use as a household glue. In the past, roofs tended t o be higher, over ten meters. This had a d e f i n i t e purpose . The roof doubled as a watchtower where men spent many hours on the a l e r t for enemies. 29 A typical interio r might look something like t h i s : Entering the door, you'd find a p l a t f o r m bed (approx. 2 X 1 meter). Called the cama tarima or cahuito, i t r i s e s more than half a meter above the floor, and i s used by the e n t i r e family. Eucalyptus boards l a i d across the bed frame support a cushion of sig SIR and eucalyptus leaves. An estera mat covers t h i s affair and handspun wool weavings or ponchos serve as blankets. In t h e back, a crude s h e l f holds gourds for s a l t , o i l b o t t l e s and other containers for cooking. An interior platform b u i l t with the remaining carrizo r i s e s two meters above the f l o o r . Grain, clothing and other perishables are s t o r e d h e r e . On the w a l l s hang a l l s o r t s of a r t i c l e s , such as bags, l a n t e r n s , p o t s , d r i e d cabuya, etc. Off to the side, a small c a r r i zo pen lined with sig sig holds a number of cuy (guinea pigs). Coy are sometimes free t o run around the house. I t i s remarkable how warm and cozy such houses can be. Near the center of the floor, a small f i r e place, fogdn, surrounded by f l a t cangagua stones, is used for cooking. Burning e u c a l y p t u s wood gives off a pleasing aroma. The smoke h e l p s season and p r e s e r v e the wood and keep down vermin. Other dwellings sometimes have a fogon i n t h e s l e e p i n g a r e a . A fogon c r e a t e s a cloud of smoke about head level. People s i t on rocks and stumps, keeping them off t h e d i r t f l o o r , but below t h e hovering smoke. Lighting, for the most part , i s poor. The window has not been developed since i t i s more important to keep out the cold winds. The l i t t l e l i g h t t h e r e i s comes from candles and sometimes kerosene lamps. The i n t e r i o r i s used for sleeping, cooking and eating, although some more e l a b o r a t e houses have a separate cook house. Socializing generally takes place outside in a courtyard The interesting p a t t e rn of chahuarqueros, carrizo, saquipata and s i g s i g i n s i d e the hut t a k e s on deeper tones w i t h age. I n some houses, a f i l m of soot w i l l further darken the interior. Governmental support of nont r a d i t i o n a l housing i s widespread, although misplaced. This i s the case n ot only i n Ecuador but t h r o u g h o u t t h e T h i r d World. 'Modern' housing i s creating rampant consumerism. I t i s diverting the efforts of those who can least afford i t , and i n the l a s t resort, money i s being spent where i t does the l e a s t good. This fosters dependency, and w o r s t of a l l , i t represent an invasion on cultures and threatens t h e i r survival. i hope I have demonstrated that i n v i r t u a l l y every respect, economically, a r c h i t e c t u r a l l y and e s t h e t i c a l l y , t r a d i t i o n a l housing i s s u p e r i o r . I t makes sense t o use l o c a l m a t e r i a l s which c o s t l i t t l e to build dwellings so well s u i t e d t o t e r r a i n and c l i m a t e . Y e t , my f i n d i n g s m e t w i t h c o n s i d e r a b l e o f f i c i a l suspicion and disbelief. Countries which f a i l t o unders t a n d t h e advantage s of t r a d i t i o n a l housing are wasting precious resources. 'Western' architecture i s i n many instances technically inappropriate. I t s p r e s e n t p o p u l a r i t y can only be e x p l a i n e d a s an u n f o r t u n a t e and c o s t l y aping of more a f f l u e n t nations. BELOW: C o s t l y "Modern" h o u s i n g . OPPOSITE ( C l o c k w i s e f r o m upper l e f t ) : Cabuya rope and bag, e s t e r a , c a r r i z o b a s k e t s , cabuya bag f o r donkeys, cabuya rope and c o n s t r u c t i o n e s t e r a . household