Assessing a Decade of Interstate Bank Branching

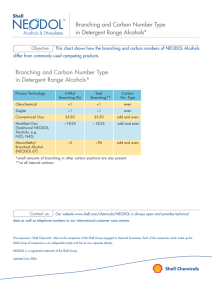

advertisement