FSD Kenya Summary Report - Oxford Policy Management

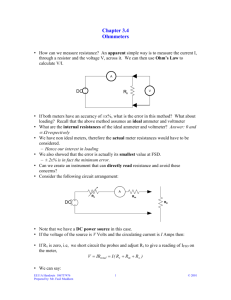

advertisement