Phenomenal Young Women: Positive Identity Development in

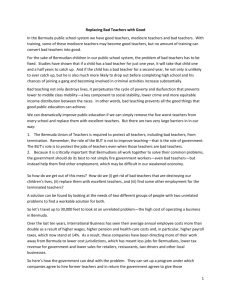

advertisement