this war is a farce - University of North Carolina Press

advertisement

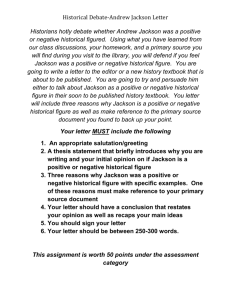

chapter 1 this war is a farce Stonewall Jackson was angry. With ‘‘no other aid than the smiles of God,’’ his brigade of Virginians had blunted the Federal advance and turned the fortunes of battle at First Manassas. But the rout of the Yankee army galled him as an empty triumph. The Confederate commanders, Gen. Joe Johnston and Gen. Pierre G. T. Beauregard, seemed content simply to hold the ground Jackson had won them. Fretting about at a field hospital just after the battle, Jackson unburdened himself on the surgeon who attended his broken finger. ‘‘If they will let me,’’ he declared, ‘‘I’ll march my brigade into Washington tonight!’’ No one let him. As July slipped into August 1861, the Confederate army of 41,000 men sank into torpor in camps around the hamlet of Centreville, just twenty miles from the defenses of Washington, D.C. An inept commissary department and uncertain railroads kept the troops hungry in a rich harvest season. Measles and chronic diarrhea laid low thousands. The liberal granting of furloughs thinned the ranks in equal measure. A shortage of arms— the chief of ordnance had only 3,500 muskets, mostly antique flintlocks, on hand—impeded recruiting.∞ Both the army and the civilian population of the South had expected that Johnston and Beauregard would advance after First Manassas at least as far as Alexandria. Sanguine spirits predicted the capture of Washington, D.C., and the defection of Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri to the Confederacy. Some, beguiled by victory, considered the war all but over. A Virginia chaplain at the front recalled meeting a high-ranking o≈cer just returned from Rich- mond who assured him: ‘‘We shall have no more fighting. It is not our policy to advance on the enemy now; they will hardly advance on us, and before spring England and France will recognize the Confederacy, and that will end the war.’’≤ Stonewall Jackson disagreed. He argued that only by carrying the fight vigorously onto Northern soil could the South expect to prevail. Delay was fatal. ‘‘We must give [the enemy] no time to think,’’ he wrote his wife Anna. ‘‘We must bewilder them and keep them bewildered. Our fighting must be sharp, impetuous, continuous. We cannot stand a long war.’’≥ Confederate inactivity after First Manassas was not simply a terrible blunder, Jackson believed, but also a dangerous repudiation of the will of God. In His divine providence, the Lord had given the Southern people a rare opportunity for securing the fruits of independence through decisive action in His name. ‘‘If the war is carried on with vigor,’’ Jackson assured Anna, ‘‘I think that, under the blessing of God, it will not last long.’’ Despite his deeply felt fears, both temporal and eternal, Jackson’s sense of o≈cial propriety sealed his lips. When asked why the army did nothing, Jackson told his subordinates, ‘‘This is the a√air of the commanding generals.’’∂ Unknown to Jackson, the commanding generals also were impatient to strike a decisive blow, the more so as spies in Washington told them a reinvigorated, and hugely superior, Federal army under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan might at any moment move against them. But without more arms and men, Johnston was loathe to advance beyond Fairfax Courthouse. At Johnston’s request, President Je√erson Davis visited army headquarters on September 30 to review the situation. For two hours Davis, Johnston, Beauregard, and Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith pored over maps and shuΔed through ordnance and troop-strength reports. ‘‘No one questioned the disastrous results of remaining inactive through the winter,’’ recalled Smith. ‘‘The enemy were daily increasing in number, arms, discipline, and e≈ciency. We looked forward to a sad state of things at the opening of a spring campaign.’’ Johnston pleaded for help. ‘‘Mr. President, is it not possible to increase the e√ective strength of this army and put us in condition to cross the Potomac and carry the war into the enemy’s country? Can you not by stripping other points to the last they will bear, and even risking defeat in other places, put us in condition to move forward?’’ How many more men would they need? Sixty thousand, said Johnston and Beauregard; fifty thousand, thought Smith. Out of the question, retorted Davis; the whole country demanded protection and arms and troops for 8 this war is a farce defense. The generals were unrelenting. Better to risk almost certain defeat on the north side of the Potomac than watch the army waste away during the winter, at the end of which the terms of enlistment of half the force would expire. But Davis was adamant. Reinforcements were impossible; there was no course but to ‘‘await the winter and its results.’’ As heartsick as his generals, Davis suggested a partial blow somewhere in the theater, perhaps a quick strike across the Potomac near Williamsport, Maryland, or Harpers Ferry, Virginia.∑ Unaware that the issue had been decided, Jackson called on General Smith, who lay sick in his tent. Jackson apologized for disturbing him, but he had come on a matter of ‘‘great importance.’’ Smith bade him proceed. Sitting himself on the ground at the head of Smith’s cot, with a confidence perhaps borne of his October 7 promotion to major general in the Provisional Army of the Confederate States, Jackson o√ered up his war strategy. With his army of raw recruits, McClellan dare not make a move until spring. Now was the time to draw troops from other points and invade: Cross the Upper Potomac, seize Baltimore, destroy the factories of Philadelphia and play havoc with Pennsylvania, take and hold the shores of Lake Erie. It could all be done, expounded Jackson. We could live o√ the land; make ‘‘unrelenting war amidst their homes, force the people of the North to understand what it will cost them to hold the South in the Union at the bayonet’s point.’’ Smith must persuade Johnston and Beauregard of the correctness—and righteousness—of his vision. Smith shook his head. Impossible, nothing he might say would do any good. But he must, countered Jackson. No, answered Smith, and to explain his reluctance he o√ered to ‘‘tell Jackson a secret.’’ ‘‘Please do not tell me any secret. I would prefer not to hear it.’’ But Jackson must know. President Davis had ruled out an o√ensive; the South would wait for McClellan’s advance, or for European recognition, as the case might be. The passion left Jackson. ‘‘When I had finished,’’ recalled Smith, ‘‘he rose from the ground, shook my hand warmly, and said, ‘I am sorry, very sorry.’ Without another word he went slowly out to his horse, a few feet in front of my tent, mounted very deliberately, and rode sadly away.’’∏ union brigadier general Frederick W. Lander was a restless spirit. Strong and fond of sports, Lander as a young man had parleyed an engineering degree from Norwich University into an assignment as a civil engineer on the Northern Pacific Railway survey of 1853. At home on the frontier, Lander returned to the Northwest the following year to lead a surveying expedition this war is a farce 9 from Puget Sound to the Mississippi River. Over the next four years, he roamed the West as superintendent and chief engineer of the Overland Wagon Road, fighting Indians and bears in about equal measure, and earning from admiring Blackfoot guides the nom de guerre of ‘‘Old Grizzly.’’ By the end of the decade, Lander had participated in five transcontinental surveys. When not challenging nature, he dabbled in poetry, writing with the same force and vigor that characterized his railroad work. In 1860 he married Jean Margaret Davenport, an acclaimed British actress. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the Lincoln administration appointed Lander a civil agent and sent him on a confidential mission to Governor Sam Houston of Texas, with authority to order Federal troops in the state to support the governor. Later, as a volunteer aide on the sta√ of General McClellan, Lander distinguished himself in the engagements of Philippi and Rich Mountain. That won him a commission as a brigadier general of volunteers and command of a brigade in Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone’s Corps of Observation near Poolesville, Maryland, across the Potomac River from a small Confederate force at Leesburg, Virginia.π Lander shared Jackson’s yearning for action. In early October he traveled to Washington to lobby for a new assignment. Ambushing Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward as they left the White House one evening, Lander promised the president he could do great things if granted a special force. With a handful of good men—loyal Virginians, whom he would raise himself —Lander would strike south and erase the ‘‘cowardly shame’’ of Bull Run, or die trying. Watching the rugged brigadier march o√, a bemused Lincoln quipped to Seward: ‘‘If he really wanted a job like that, I could give it to him. Let him take his squad and go down behind Manassas and break up their railroad.’’ The commanding general of the army, Winfield Scott, took Lander more seriously. On October 13 he o√ered Lander, whom he once called the ‘‘great natural American soldier,’’ command of a newly created Department of Harpers Ferry and Cumberland, which embraced a 120-mile stretch of the strategically critical Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Thirty miles of the line cut through hostile territory.∫ Lander accepted the assignment. He returned to Poolesville just long enough to tender his resignation from McClellan’s moribund army, then hurried back to the War Department to consult with Scott. Confederate cavalry and local militia had burned railroad bridges and torn up much of 10 this war is a farce the track in Virginia, but Lander was confident that he could reopen the line quickly. A√airs in western Virginia certainly seemed propitious of success. McClellan’s successor to departmental command, Brig. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, had swept poorly led Southern forces eastward toward the Allegheny Mountains. Reinforced and united under Maj. Gen. Robert E. Lee, the Confederates maintained a tentative presence in the Great Kanawha Valley, which Rosecrans threatened to disrupt. Nearer to Lander’s new department, Brig. Gen. Benjamin F. Kelley commanded a brigade of Ohio and loyal Virginia regiments at Grafton in what was called the Railroad District of Rosecrans’s department.Ω Kelley was within striking distance of Romney, Virginia, a village of five hundred with an importance far beyond its humble size. From Romney, the excellent Northwest Turnpike ran east forty miles to Winchester, which was key to the Confederate defense of the Lower Shenandoah Valley. Romney was the principal town of the fertile South Branch Valley. Wide meadows on either side of the South Branch of the Potomac River yielded large crops of corn and o√ered ideal pasturage for cattle. Tucked among a patchwork of ridges, ravines, and low mountains on the east bank of the South Branch, Romney not only controlled the valley, but it also commanded the sixty-mile length of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad most critical to Lander’s new department. From Romney, the Confederates could reach the track in a short day’s march. But with Romney in Federal hands, marauding Confederates would be hard pressed to operate against the railway. Lander understood this, and he urged General Scott to order Kelley to seize Romney and assume command of the Department of Harpers Ferry and Cumberland until Lander arrived. Scott complied, and on October 22 Lander repaired to his District of Columbia home to prepare for his new post.∞≠ An unexpected clash the previous day involving his old brigade interrupted Lander’s plans. General Stone had taken his Corps of Observation across the Potomac to do battle with a Confederate force at Ball’s Blu√. In the ensuing fiasco Col. Edward D. Baker, a close friend of President Lincoln, was killed and the surviving Union troops were stranded. That evening a War Department courier delivered a short telegram from McClellan to Lander’s E Street home ordering the general to return to his former command. Lander set out at once and the next morning took command of two thousand Federal troops on the Virginia shore at Edwards Ferry, ten miles downriver from Ball’s Blu√. Lander this war is a farce 11 was hit early in the day’s fighting. A Rebel bullet smashed into his left leg, boring his bootstrap deep into the calf muscle. Refusing aid, Lander hobbled about in agony until the fight was over. A surgeon then cleaned bits of boot leather from the gaping hole, pronounced the wound ‘‘not at all dangerous,’’ then remanded Lander to the care of his wife. Spitting epithets over the poor planning and wasted sacrifice of life that characterized Stone’s sorry little campaign—‘‘This war is a farce,’’ he told a friend, ‘‘bloodless nerves ruin the roast’’—Lander rode painfully back to his district home to convalesce. While he laid abed, his chief patron, General Scott, retired, and George McClellan replaced him as commanding general of the Northern armies. McClellan wanted a quiet winter. Undoubtedly concerned that the impetuous Lander would bring on a battle to reopen the Baltimore and Ohio as soon as he was healthy, McClellan terminated his new military department.∞∞ inactivity was anathema to Stonewall Jackson. Rebu√ed in his calls for an o√ensive, Jackson devoted himself to improving his brigade, already the most e≈cient in Johnston’s army. Other commands melted away, as troops took leave in large numbers to visit family or harvest crops, but Jackson granted no furloughs. His devotion to duty was absolute, and he expected nothing less from his o≈cers and men. When Col. Kenton Harper of the 5th Virginia appealed to Jackson in late August for emergency leave to visit his terminally ill wife, he met with a harsh rebuke. ‘‘General, my wife is dying! I must see her!’’ implored Harper. A look of sadness betrayed Jackson’s inner struggle, but he held firm. ‘‘Man,’’ he asked Harper, ‘‘do you love your wife more than your country?’’ Harper’s answer was a letter of resignation.∞≤ Hypocrisy can sometimes catch the best of men unawares. While Colonel Harper journeyed home to Staunton to bury his wife, Mary Anna Jackson was on her way to Centreville to visit her husband. General Jackson commandeered an ambulance to meet her at the Manassas railhead, whisked her o√ to church services with the Stonewall Brigade, and then set her up in a farmhouse near headquarters. While Jackson drilled his brigade incessantly, Anna reveled in army life, entertaining high-ranking callers and generally enjoying her role as belle of the ball. Four times a day, in ninety-minute blocks, Jackson had the brigade on the parade ground. Their firm stand at Manassas had earned the Virginians and their commander the sobriquet ‘‘Stonewall.’’ But tenacity on the defense was but one ingredient of military success; now they would learn to march and attack as one. Said an early Jackson biographer: ‘‘Shoulder to shoulder they advanced and retired, marched and countermarched, massed in 12 this war is a farce column, formed line to front or flank, until they learned to move as a machine, until the limbs obeyed before the order had passed from ear to brain, until obedience became an instinct and cohesion a necessity of their nature.’’ Amid the general apathy that had descended on the army, Jackson’s men worked hard. When not drilling, they stood inspection, policed their camps, or picketed the perimeter. ‘‘Every o≈cer and soldier,’’ a≈rmed Jackson, ‘‘who is able to do duty ought to be busily engaged in military preparation by hard drilling, in order that, through the blessing of God, we may be victorious in the battles which in His all-wise providence may await us.’’∞≥ It was not only his men who learned. Ever a close student of war, Jackson reflected on his actions at First Manassas, and from them derived tactical principles to guide him in the campaigns ahead. As a young lieutenant of artillery in the Mexican War, Jackson had learned how to deploy artillery to its best advantage. Running his section up to the walls of Chapultepec, far in advance of the infantry, Jackson had given shot for shot with the heavy guns of the castle until support reached him. His feat of daring inspired an assault that carried the works and won the battle. Just as the daring of a few well-served cannons might inspire the infantry, so too could their capture demoralize the ranks, as happened when Jackson’s Virginians mowed down the gunners and horses of Ricketts’s and Gri≈n’s regular batteries at Manassas. Jackson’s ideas regarding the role of infantry were as aggressive as his artillery tactics. ‘‘I rather think,’’ he said after First Manassas, ‘‘that fire by file [independent firing] is best on the whole, for it gives the enemy an idea that the fire is heavier than if it was by company or battalion [volley firing]. Sometimes, however, one may be best, sometimes the other, according to circumstances. But my opinion is that there ought not to be much firing at all. My idea is that the best mode of fighting is to reserve your fire till the enemy get—or you get them—to close quarters. Then deliver one deadly, deliberate fire—and charge!’’∞∂ No less important than controlling men in combat was the need to control oneself. Jackson knew himself to be imperturbable under fire, but some had mistaken his calm determination at Manassas for simpleminded indi√erence. Paying a call on Jackson three days after First Manassas, Capt. John D. Imboden asked him the secret of his equanimity in battle. ‘‘General,’’ he inquired pointedly, ‘‘how is it that you can keep so cool, and appear so utterly insensible to danger in such a storm of shell and bullets as rained about you when your hand was hit?’’ Perhaps because his battery had served Jackson faithfully at Manassas, this war is a farce 13 P E N N S Y LVA N I A Cumberland . Williamsport Unger’s Martinsburg Store Bunker Bloomery Hill Gap Stephenson’s Charlestown Depot Harpers Romney R. R. M ts. B aca ig C ny he Frederick Ferry Leesburg Po tom ac R . Snicker’s Gap Manassas Thoroughfare t. Gap M Gap n Front Royal Manas Edinburg tte Manassas u sas G n ey Chester a Jct. ap R l l s a . R. V as Mt. Jackson Warrenton Gap ge M Franklin ia Meem’s Thorton dr North Fork an Bottom Luray Gap lex A . New & R White House Bridge ge R. Market Culpeper an C. H. Or Columbia Bridge Rappah an Harrisonburg Conrad’s no ck t Store Cross Keys . S ou R n R. a d Orange pi a Swift Run R dle C. H. Fredericksburg Gap Mid R. Port Stanardsville Republic Brown’s Woodstock Petersburg hF ll P Bu Monterey o rk ast ur eM t. Al Pa leg Kernstown She Moorefield Winchester Berryville h oa nd Middletown na Newtown Strasburg po n P c ma oto M A RY L A N D Bath R. & B. R. R O. Dam No. 5 C & O Canal Hancock Chesapeake & Ohio Canal McDowell ue ge M e& g an George Skoch . ts Al ria R. Charlottesville Cent ral R . R. Hanover Jct. Jame s R. R. Virg inia d an ex Or Meechum’s Station R. R. Bl d Ri Gordonsville P. R. F. & Waynesboro Lexington Gap Rockfish Gap Staunton VIRGINIA 0 20 Miles Richmond map 1. Area of Operations, January–June 1862 Imboden was at ease asking the reticent and intensely private Jackson so personal a question. And Jackson obliged him with an answer. ‘‘Captain,’’ he said gravely, ‘‘my religious belief teaches me to feel as safe in battle as in bed. God has fixed the time for my death. I do not concern myself about that, but to be always ready, no matter when it may overtake me.’’ Pausing, he looked the young captain in the face, then added, ‘‘That is the way all men should live, and then all would be equally brave.’’∞∑ Although careful not to force his faith on them, Jackson had a profound concern for the spiritual welfare of his men. In late October he invited the Reverend Dr. William S. White, pastor of the Lexington Presbyterian Church, which Jackson had attended in peacetime, to preach to the command. For five days and nights White ministered to the Virginians, reserving time in the morning and evening to lead the worship service at headquarters. Jackson 14 this war is a farce thrilled to these spiritual retreats with ‘‘a beaming face and warm abandon of manner.’’ He prayed with uncommon intensity, remembered White. ‘‘He thanked God for sending me to visit the army, and prayed that He would own and bless my ministrations, both to o≈cers and privates, so that many souls might be saved. He pleaded with such tenderness and fervor that God would baptize the whole army with His holy spirit, that my own hard heart was melted into penitence, gratitude, and praise.’’∞∏ White unexpectedly found himself with more to do than spread the Gospel. On the morning of October 23, while White prepared for his daily ministrations, a troubled General Jackson handed him a letter he had just received. White studied it closely: Richmond, October 21, 1861. Major-General Jackson, Manassas: sir: The exposed condition of the Virginia frontier between the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains has excited the deepest solicitude of the Government, and the constant appeals of the inhabitants that we should send a perfectly reliable o≈cer for their protection have induced the Department to form a new military district, which is called the Valley District of the Department of Northern Virginia. In selecting an o≈cer for this command the choice of the Government has fallen on you. This choice has been dictated, not only by a just appreciation of your qualities as a commander, but by other weighty considerations. Your intimate knowledge of the country, of its population and resources, rendered you peculiarly fitted to assume this command. Nor is this all. The people of that district, with one voice, have made constant and urgent appeals that to you, in whom they have confidence, should their defense be assigned. The administration shares the regret which you will no doubt feel at being separated from your command when there is a probability of early engagement between the opposing armies, but it feels confident that you will cheerfully yield your private wishes to your country’s service in the sphere where you can be rendered most available. In assuming the command to which you have been assigned by general orders, although your forces will for the present be small, they will be increased as rapidly as our means will possibly admit, whilst the people will themselves rally eagerly to your standard as soon as it is known that you are to command. In a few days detailed instructions will be sent you this war is a farce 15 through the Adjutant-General, and I will be glad to receive any suggestions you may make to render e√ectual your measures of defense. I am, respectfully, your obedient servant, j. p. benjamin Acting Secretary of War The good reverend might have expected Jackson to welcome the news. But Jackson instead paced the ground in pained uncertainty. ‘‘Such a degree of public confidence and respect as puts it in one’s power to serve his country should be accepted and prized,’’ he conceded, ‘‘but, apart from that, promotion among men is only a temptation and a trouble. Had this communication not come as an order, I should instantly have declined it, and continued in command of my brave old brigade.’’∞π Among his fellow generals, some thought it best that he decline. Beyond question he had shown his mettle as a brigade commander, but would he do as well in a larger role? Said one high-ranking skeptic, ‘‘I fear the government is exchanging our best brigade commander for a second or third class major general.’’∞∫ General Johnston was reluctant to part with Jackson and perturbed that neither the president nor Secretary Benjamin had consulted him on the move. So he stalled, ignoring an October 28 War Department order directing the immediate reassignment of Jackson. Appeals for Jackson’s service rang loudly from the Shenandoah Valley. ‘‘From the latest intelligence from that country I am inclined to think that it may be expedient to send Major General Jackson to his district,’’ Johnston conceded halfheartedly to Samuel Cooper, adjutant general of the army. ‘‘It is reported that the enemy intend to repair the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and put it in operation. It is of great importance to us to prevent it. For this I will send General Jackson to his district whenever there is a prospect of having such a force as will enable him to render service.’’∞Ω November 4 brought a third set of orders for Jackson’s reassignment. With or without troops, Jackson must go. In a letter to Anna that morning, he tried to put the best face on matters. ‘‘I am assigned to the command of the military district of the Northern frontier, between the Blue Ridge and the Allegheny Mountains, and I hope to have my little dove with me this winter. How do you like the program?’’ he asked playfully. ‘‘I trust I may be able to send for you after I get settled. I don’t expect much sleep tonight, as my desire is to travel all night, if necessary, for the purpose of reaching Winchester before day tomorrow. My trust is in God for the defense of that country. I shall have great labor 16 this war is a farce to perform, but, through the blessing of our ever-kind Heavenly Father, I trust that He will enable me to accomplish it.’’≤≠ One painful task remained to Jackson before leaving. He must bid farewell to his old brigade. The regimental colonels came to his tent first to say goodbye. A deputation of regimental and company line o≈cers filed through a little before noon. He cordially shook the hand of each. The last to enter the tent was Lt. Henry Kyd Douglas, a brash young Virginian with a high opinion of himself and an even higher opinion of his commander and the brigade he was leaving. Everyone wished him well, ventured Douglas, but the men of the Stonewall Brigade hoped he would not forget them. Jackson’s lips tightened and his eyes brightened. ‘‘I am much obliged to you, Mr. Douglas, for what you say of the soldiers; and I believe it. I want to take the brigade with me, but cannot. I shall never forget them. In battle I shall always want them. I will not be satisfied until I get them. Good-bye.’’ An hour later, on his favorite mount, ‘‘Little Sorrel,’’ Jackson rode out with his sta√ to the parade field, where the brigade stood at close column of regiments under a cold, slate-gray sky. Removing his hat, he o√ered his men thanks for their sacrifices and a ‘‘heartfelt goodbye.’’ Then, rising in the stirrups and raising his arms, he exclaimed in his sharp, high-pitched western Virginia drawl: ‘‘In the Army of the Shenandoah you were the First Brigade; in the Army of the Potomac you were the First Brigade; in the Second Corps of the army you were the First Brigade; you are the First Brigade in the a√ections of your general; and I hope by your future deeds and bearing that you will be handed down to posterity as the First Brigade in this, our second War of Independence. May God Bless you! Farewell!’’≤∞ this war is a farce 17