So It Goes: Resignation or Way of Being?

advertisement

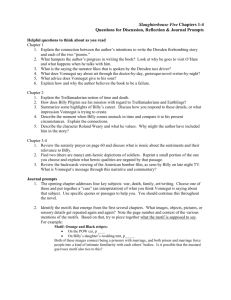

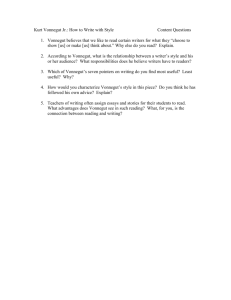

Unit Title: So It Goes: Resignation or Way of Being? Literature of War Time: Five Weeks Subtopics: 1. The Public and The Private Self (American vs. Russian) 2. Rule of Law / American Dream 3. Spiritual Awareness Course: An Introduction to Literary Criticism Grade: 12th Grade English, College Preparatory Level Introduction: At the outset of the unit, students will have already studied the narrative structure of short fiction. Students will understand the trajectory and chronological unfolding of short fiction, as first articulated by Aristotle in his Poetics. Students will understand the roles of exposition, inciting incident, crisis, conflict, climax, dénouement, and falling action. Students will understand that narratives moving along predictable trajectories are, for the most part, wholly “Western” in their construction; in short, students will grasp the narrative arc of the Western literature. Furthermore, students will have already studied the dominant literary terms; they will readily distinguish between works of realism, satire, fantasy, memoir, autobiography, and science fiction. Our unit of Comparative Literature will center on Vonnegut’s Slaughter-House Five and Solzhenitsyn’s A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Supplementary texts will be introduced alongside these longer works, both to support existing themes within the novels and to offer alternate perspectives. Both Slaughterer-House Five and A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich are semi-autobiographical texts. Both Vonnegut and Solzhenitsyn were war-time prisoners. Both novelists employ a kind of alter-ego as the central protagonist of their stories. The works have much in common. The differences between the works, however, will prove the primary focus of our study. Slaughter-House Five mixes the conventions of genres. It plays with autobiography, science fiction, memoir, and fantasy. On the other hand, A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich is realistic in its treatment of time and space. Where Slaughter-House Five at times wholly abandons any sense of chronology, A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich is just that: a single day in the life of its protagonist, from “morning reveille” to the “last clang of the rail.” Flanigan, Literature of War The central conceit of the unit explores the implications of Vonnegut’s famous expression: “So it goes.” Throughout Vonnegut’s work, the expression appears in the aftermath of death: it is reaction to the presence of death in any form. It does not exclude nor differentiate. Be it soldier or bug, Vonnegut offers the same forlorn expression. Arguably, the phrase functions as a kind of resignation in the face of horror. For Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut’s alter-ego, the utterance is comforting. It abdicates Pilgrim’s sense of agency. It eliminates his personal responsibility. Instead of confronting the atrocities of the world, he accepts them as beyond his control. More exactly, he [either Vonnegut or Pilgrim, or both] “pretends” to accept them as beyond his control. Vonnegut is determined that the expression grow to assertion, become almost mantra for Pilgrim and perhaps the reader, by extension. Vonnegut, of course, saturates the phrase with irony, as Slaughter-House Five stands as an anti-war novel. Vonnegut himself doubted the novel’s ability to change anything. “Might as well stop a glacier,” he asserts. The novelist asks the reader: Can we [you] change anything? Solzhenitsyn’s theme is not as ironic or immediately accessible, but it serves the same purpose. If one cannot control one’s circumstances, what should one do? How best to fill the day? The novel suggests: When one cannot alter one’s predicament, it’s best to quit trying. For Shukov, it’s best to get on with merely “living,” however poor, narrow, or confined that “living” might be. Ivan Denisovich Shukov is an innocent man, falsely imprisoned. In the world of the novel, his innocence is irrelevant. Solzhenitsyn wastes no time exploring injustice. To what end, after all? The writer does not take on the injustice of history; he takes on a single day. Shukov, unlike Billy Pilgrim, does not “lose his mind” in his grotesquely unjust circumstances. Rather, he bears his lot with the calm steadfastness that comes only from having no agency to lose in the first place. His attitude is Russian. Whereas Billy Pilgrim, the disillusioned American, must come to terms with the personal costs of war—and in effect, lose his mind altogether—Shukhov endures the costs “almost happily.” Is this profound distinction national? Is it defined by arching ideologies? Pilgrim is reared in the wash of the American Dream, but no such dream frames Shukov. In the face of dire circumstances, Denisovich does not lose himself. He pockets bread scraps and accepts his lot for what it is. Shukov embodies what Pilgrim can only pray for: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change.” But to what God, exactly, does Pilgrim pray? Is it the same God who watches silently over Shukov’s prison, wherein the S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 2 Flanigan, Literature of War captives below assert: “if one suffers as a Christian, let him not be ashamed, but under that name, let him glorify God.” Contemporary Comment: Prelection “When Russians engag[e] in brooding self-analysis, they [are] much more likely to engage in self-distancing, or looking at the past experience from the detached perspective of someone else. Instead of reliving their confused and visceral feelings, they reinterpre[t] the negative memory, which help[s] them make sense of it. According to the researchers, this lead[s] to significantly less “emotional distress” among the Russian subjects. (It also [makes] them less likely to blame another person for the event.) Furthermore, the habit of self-distancing seem[s] to explain the striking differences in depressive symptoms between Russian and Americans. Brooding [isn’t] the problem. Instead, it [is] brooding without self-distance.” 1 Critical Question: Notebook 1. How does “self-distancing” affect point-of-view? 2. Does “self-distancing” affect a narrator’s reliability? Provide a specific example. Unit Objectives: 1. From an historical context, identify the paramount differences between The United States and The Soviet Union (Russia) in terms of their respective involvement in World War II; 2. Consider the fundamental differences between the ideologies of Western Democracy and Communism; 3. Explore how these competing ideologies affect the psychology of characters, as revealed by each country’s literature; 4. Specifically, concentrate on the representation of the “individual” within the comparative literature in response to the trauma of war and imprisonment; 5. Draw conclusions about the commonalities of the human experience and human condition within American, British, and Russian Literature; and, 6. Consider how these findings shape contemporary relations between nations, with emphasis on the relations between The United States and Russia. 1 Lehrer, Jonah. “Why Russians Don’t Get Depressed.” Wired, 2010. http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2010/08/why-russians-dont-get-depressed/ S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 3 Flanigan, Literature of War I. Topic: So You Think You Know Better? Misunderstandings and Walking on Water Text: Tolstoy, Leo. “The Three Hermits.” Short Shorts: An Anthology of the Shortest Stories. Eds. Irving Howe, et al. New York: Bantam Book, 1982. 3-10. Thematic Tie: Learning by Sight and Sound (Short Story, Traditional, Russian) Time: (40 min) Objectives: 1. Generate: List of what students know about Russia 2. Explore: stereotypes, history, propaganda; work to draw true and false conclusions 3. Link to short narrative; religion as analog between cultures. What are shared expectations? 4. Who is truly informing whom here? 5. How does the “learner” have to adjust in order to receive new information? 6. How do Americans need to adjust to receive new information about Russia? Vice versa? 7. Why is “learner” (Bishop) so certain of his methods and way of being? 8. What changes him? Connection to students / stress openness to new information, new eyes Assessment: In-class reading, journaling, shared response, and roundtable discussion Journal Questions: 1. Why does the Bishop conclude, “Your own prayer will reach the Lord, men of God. It is not for me to teach you. Pray for us sinners”? 2. How do we distinguish between who we “need to teach” and “from whom we learn”? 3. Are these relationships dynamic or static? II. Topic: An American’s Imprisonment During World War II Text: Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughter-House Five. New York: Dell Publishing, 1966. Thematic Tie: Foundational Text of Unit (Novel: Russian, Memoir, Autobiography, Fantasy, Science-Fiction) Time: (2 weeks, outside reading) Objectives: S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 4 Flanigan, Literature of War 1. Establish first longer text in unit; read over two-week period 2. Function as the primary comparative text to Solzhenitsyn’s novel 3. Historical problem of Dresden Fire Bombing 4. Agreements between Axis and Allies 5. Review concept of satire (art of diminishment); early link to Dr. Strangelove 6. Intentionality of Anti-war novel 7. Inability of Vonnegut to narrate along traditional “western arc” 8. Blending of conventions: memoir, autobiography, science fiction, fantasy 9. Necessity of alter-ego for author; early link to Solzhenitsyn 10. Aspects of “free-will” and spirituality; religious responsibility 11. Responsibility of the individual 12. Message is the medium = war is hell, confusing, unknowable, and untellable 13. Explore popularity of the novel as typically American. Why and how is novel American? 14. Billy Pilgrim’s PTSD as symptom of his inability to “distance himself from himself” Assessment: Weekly reading quizzes, journaling, roundtable discussion, blog, formal exam Written Exam Questions: The year is 1969, and you are a professional literary critic. You have been asked by an Independent Publisher to review Kurt Vonnegut’s new novel, Slaughterhouse Five. The publisher cannot decide how to market the book in the current climate of social unrest. The main questions put before you are: 1. Is Slaughterhouse Five an anti-war novel? How exactly does it fulfill that role or fail to fulfill that role? 2. Is it a work of fiction, of non-fiction, of autobiography, or memoir? 3. Is it a moral tale? If so, what is the moral? In a brief, well-considered, three-paragraph essay, address the publisher’s questions. In your response, draw on your extensive understanding of the novel’s content and its construction. To bolster your review, quote the text where and when appropriate. High-light all textual citations. Short Response Questions: 1. In the first chapter of the novel, where is the author living? S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 5 Flanigan, Literature of War 2. Vonnegut plans to make a trip to see O’Hare in which city? 3. Why doesn’t Mrs. O’Hare want Vonnegut to write a war story? 4. Vonnegut and O’Hare travel together to what city? 5. What souvenir did Vonnegut bring home from the war? 6. Name one of the two persons to whom the novel is dedicated. 7. What is the name of the town and state where Billy Pilgrim was born and lived? 8. What is referred to throughout the book as having the color of “blue and ivory”? 9. What are the names of Billy’s two children? 10. What was Billy’s rank as a soldier in the war? 11. Name the members of the “Three Musketeers.” 12. Which American soldier blames Billy for his death? 13. Which character is going to take revenge upon Billy for the death of his friend? 14. What is the last word of the novel? 15. What does Paul Lazzaro claim to have fed to a dog? 16. Complete this quote: “If you are ever in Cody, Wyoming, just ask for…!” 17. Who keeps repeating the phrase, “This ain’t bad, this ain’t nothing at all”? 18. By what means does Billy travel to Tralfamadore? 19. Why is Edgar Derby executed? 20. Where does Billy meet Eliot Rosewater? 21. What is the primary reason for Billy’s wealth? 22. Why does Billy Pilgrim keep the name “Billy” throughout his adult life? 23. How did Paul Lazzaro earn his living in Cicero, Illinois? 24. In how many dimensions do Tralfamadorians claim to see? 25. What two items does Billy find in the lining of the coat given him as a prisoner of war? 26. What does Billy give his wife for their eighteenth wedding anniversary? 27. What is the date of the Dresden bombing? 28. Billy gets on a talk radio show in New York and discusses what? S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 6 Flanigan, Literature of War 29. Who was Billy’s girlfriend in Tralfamadore? 30. How had Billy’s girlfriend made a living on Earth? 31. After the bombing, Billy and the other prisoners were put to work doing what? 32. In what town does Kilgore Trout live? 33. Where does Billy meet Professor Rumfoord? 34. How did Billy lose his wife? 35. How does Billy lose his own life? Journal Questions / Roundtable Discussion: 1. The following passage is a description of the Tralfamadore novel. State whether this description is appropriate for Vonnegut’s novel, Slaughterhouse Five. There isn’t any particular relationship between all the messages, except that the author has chosen them carefully, so that, when seen all at once, they produce an image of life that is beautiful and surprising and deep. There is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no causes, no effects. What we love in our books are the depths of many marvelous moments seen all at one time (88). 2. Explain the relevance of the following passage in terms of Vonnegut’s attempt to write an anti-war novel. Earthlings are the great explainers, explaining why this event is structured as it is, telling how other events may be achieved or avoided. I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is (86). III. Topic: Biographical Information on Kurt Vonnegut Text: Smith, Dinitia. “Kurt Vonnegut, Novelist Who Caught the Imagination of His Age, Is Dead at 84.” New York Times 12 April 2007. P1 Thematic Tie: Information of Author of Slaughter-House Five (Obituary) Time: (40 min) S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 7 Flanigan, Literature of War Objectives: 1. Provide background on Vonnegut 2. Vonnegut’s Worldview 3. Relay anecdote of Vonnegut’s address at The Ohio State University (His last speech for money) 4. Allow voice of author to be “heard” outside of novel 5. Relation of the person to the author 6. Introduce concept of “The Intentional Fallacy” 7. Explore Vonnegut’s politics and evolving world-view 8. Consideration of Slaughter-House Five’s critical reception since publication in 1969 Assessment: In-class reading, roundtable discussion Journal Question: 1. How does the information contained within the obituary affect or augment your understanding of Slaughter-house Five? 2. How you describe Vonnegut’s attitude? How does Smith create this tone? 3. How much attention should we give to the “life” of author? Does it matter? 4. Does it matter, particularly, in the case of Slaughter-house Five? Why? 5. If you could ask Vonnegut one question, what would it be? Why? IV. Topic: Imprisonment Under Stalin: Companion Text to Slaughter-House Five Text: Solzhenitsyn, Alexander. A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. New York: Signet Classic, 1963. Thematic Tie: Foundational Text of Unit (Realistic Novel) Time: (2 weeks, outside reading) Objectives: 1. Establish second longer text in unit; read over two-week period 2. Review concept of narrative realism; passages to support; lack of science-fiction, fantasty 3. Establish tie to Slaughter-House Five; first significant comparative text 4. Learning to read novel “x” in terms of novel “y” a. Would Russian students read our “y” in terms of their “x”? Why? S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 8 Flanigan, Literature of War 5. Is the medium still the message? Why so brief? 6. Revisit concepts: free-will, personal responsibility, spirituality 7. Shukov as alter-ego for Solzhenitsyn; Pilgrim for Vonnegut 8. Learn about the “gulag”; newspaper article to follow 9. Shukov accepts “what he cannot change…” Why? How different than Pilgrim? 10. Is serenity learned? Religious context / lesson? 11. Could Shukov inform Pilgrim’s world vision? Vice-versa? 12. Central claim of unit: Each protagonist could inform the other. How? Why? a. Tie back to “The Three Hermits” 13. Relation of central claim to contemporary relations between foreign countries Assessment: Weekly reading quizzes, journaling, blog, take-home essay Journal Questions / Roundtable Discussion: 1. Write your thoughts on the following quotations by Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Respond to at least two: a. “I can say without affectation that I belong to the Russian convict world no less than I do to Russian literature. I got my education there, and it will last forever.” b. “I have spent all my life under a Communist regime, and I will tell you that a society without any objective legal scale is a terrible one indeed. But a society with no other scale but the legal one is not quite worthy of man either.” c. “The next war...may well bury Western civilization forever.” [Note: He means World War III] d. “You can have power over people as long as you don't take everything away from them. But when you've robbed a man of everything, he's no longer in your power.” e. Find another Solzhenitsyn quotation. Be sure to provide accurate citation. Explain: Why are you particularly drawn to this quotation? What about his statement is challenging, provocative, interesting? If applicable, do you agree or disagree with his sentiment? Why? Blog Prompt: S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 9 Flanigan, Literature of War 1. Discuss one specific aspect of the novel A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and explain how it relates, directly, to at least two of your journal quotations. You must cite the novel. Be prepared to share your responses. Essay Prompt: 1. Were Ivan Denisovich to read Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, would Denisovich agree or disagree with the sentiment about death: “So it goes”? Why or why not? In your response, be sure to cite A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. V. Topic: Biographical Information on Solzhenitsyn Text: Solzhenitsyn, Alexander. “Nobel Lecture.” NobelPrize.org. 2010. <http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/ literature/laureates/1970/solzhenitsyn-lecture.html> Thematic Tie: Information on author of A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (Nobel Speech) Time: (40 min) Objectives: 1. Provide background on Solzhenitsyn 2. Solzhenitsyn’s worldview 3. Allow voice of author to be “heard” outside of novel; compare to Vonnegut’s obituary 4. Relation of the person to the author 5. Review concept of “The Intentional Fallacy” 6. Explore Solzhenitsyn’s politics and world-view; contrast to Vonnegut 7. Consideration of A Day in Life of Ivan Denisovich’s critical reception since publication in 1962 8. The problem of publication under Soviet state 9. Reclusive nature of the author 10. Solzhenitsyn’s opinion on the “West” 11. Special consideration on author’s views of capitalism and democracy versus socialism Assessment: Roundtable discussion, journaling Journal Question for Roundtable Discussion: How are the following views expressed in Solzhenitsyn’s novel? S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 10 Flanigan, Literature of War 1. “…And in misfortune, and even at the depths of existence—in destitution, in prison, in sickness—his sense of stable harmony never deserts him…” (Part 1) 2. “…Do not believe your brother, believe your own crooked eye…” (Part 3) 3. Reflect again on the following description and definition of art, as offered by Solzhenitsyn in his acceptance speech. Following, address the questions below. “But shall we ever grasp the whole of that [Art] light? Who will dare to say that he has DEFINED Art, enumerated all its facets? Perhaps once upon a time someone understood and told us, but we could not remain satisfied with that for long; we listened, and neglected, and threw it out there and then, hurrying as always to exchange even the very best — if only for something new! And when we are told again the old truth, we shall not even remember that we once possessed it.” i. In your own words, paraphrase Solzhenitsyn’s point. ii. Does his point speak to the responsibility of the critic? VI. Topic: War is Hell: Psychological Effects of Military Service Text: Owen, Wilfred. “Dulce et Decorum Est.” Arp 651-652. Thematic Tie: World War I Poem: Subverts the Idea of Military Service as Glorious (Poem) Time: (40 min) Objectives: 1. Provide links between World Wars: What’s changed? 2. Link back to study of British Literature: Anglo-Saxon to Modern; complete reversal in idea of heroism 3. How is the “idea” of glory subverted by the tone of the poem? 4. Help students to see similar themes expressed in different genres / historical periods 5. How does Owen inform Vonnegut and Solzhenitsyn? 6. How does modernity and technology affect warfare? 7. Do the technological advances of warfare affect the psychology of the human? How? 8. Specifically, does Owen’s worldview align more closely to Vonnegut’s or Solzhenitsyn’s? Assessment: Roundtable discussion 1. Do the following lines apply to Billy Pilgrim? Why or why not? S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 11 Flanigan, Literature of War a. My friend, you would not tell with such high zest To children ardent for some desperate glory, The old Lie, Dulce et Decorum est Pro patria mori. VII. Topic: The Privacy of The War Experience: Indifference to Events Below Text: Yeats, William Butler. “An Irish Airman foresees His Death.” Bartleby: Great Books Online. 2010. < http://www.bartleby.com/148/3.html> Thematic Tie: World War I Poem: Soldier Resigns Himself to Fate (Poem) Time: (40 min) Objectives: 1. Provide additional link between World Wars 2. A “quieter perspective’; personal and “balancing” 3. Full embodiment of technologies’ abilities to “numb” the effects of war; one’s participation in 4. How is the idea of glory handled in this poem? Does it speak to Owen’s concerns? Does it counter them? 5. Is the poem realistic? How? 6. “So it goes”? “….in balance with this life / this death…”? 7. Explore the personal responsibilities of any soldier to his nation Assessment: Roundtable discussion 1. What is the responsibility of the pilot as a subject of the United Kingdom? VIII. Topic: Fantasy: The Lighter Side of “Crazy” Text: Thurber, James. “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” Zoetrope: All Story. 2010. <http://www.all-story.com/issues.cgi?action=show_story&story_id=100> Thematic Tie: Alter Ego and Fantasy in Short Fiction (Humor / Short Story) Time: (40 min) Objectives: 1. Text to accompany Slaughter-House Five S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 12 Flanigan, Literature of War 2. Accessible introduction for function of “alter ego” in literature 3. What do Walter Mitty and Billy Pilgrim have in common? 4. Why does Mitty fantasize himself as a war hero, among other fantastic heroes? 5. How are war heroes categorized in the modern mind? 6. Is Mitty’s “fantastic life” some kind of coping mechanism? Is Billy Pilgrim’s? 7. Is Mitty suffering like Pilgrim? How do we know? 8. Connections between Mitty and Pilgrim’s domestic life Assessment: Reading quiz, recall questions, roundtable discussion Reading Quiz: 1. At the opening of the narrative, Mitty’s wife is upset about what? [Speed of his driving] 2. At the opening, in what branch of the military does Mitty fantasize he is part? [Navy] 3. For what item does Mrs. Mitty send Walter to purchase? [Overshoes] 4. About what profession does Mitty next fantasize? [Surgeon] 5. What does Mrs. Mitty require now be done at the mechanic’s garage? [Remove snow chains] 6. In the next fantasy, why does Mitty take the stand at the trial? [Firearms expert] 7. Where does Mrs. Mitty finally find Walter? [Dreaming in a hotel chair] 8. Finish Walter’s phrase to his wife: “Does it ever occur to you that I sometimes _____?” [Thinking] 9. What does Mrs. Mitty insist she must do when they arrive back at home? [Take Walter’s temperature] 10. After his imagined last cigarette, what does Walter stoically turn to face? [Imagined firing squad] Journal Question: 1. What’s going on with Walter Mitty’s mind? Is he simply a day-dreamer, or do you think his “condition” is indicative of a deeper psychological problem? 2. Compare and contrast Mrs. Mitty and Valencia. Do the characters serve a similar function in their respective narratives? IX. Topic: The Gulag: Then and Now S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 13 Flanigan, Literature of War Text: Frazier, Ian. “On the Prison Highway; Our Far-Flung Correspondents.” The New Yorker Aug. 2010: 28. Thematic Tie: Background Information on Stalinist Prison Camp: Historical Context for A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (Journal Article, Contemporary) Time: (Outside reading, approximately one hour) Objectives: 1. History of the gulag 2. Provide explanation and visual context to accompany Solzhenitsyn’s novel 3. Explore how contemporary the article is: What does this teach about the distance of history? 4. Analyze Frazier’s concept of visual “absence” as it relates to the psychology of protagonists 5. Comparison between journalistic account of gulag and Solzhenitsyn’s artistic rendering 6. Opportunity for journaling on the psychology of imprisonment Assessment: Outside reading, in-class reading, blog Blog: Respond to either questions 1 and 2 or questions 3 and 4. 1. Though it is hard to do, imagine you are prisoner in the gulag. What might be some of your main concerns? a. Physical? b. Spiritual? 2. Do you think you would have similar concerns as Shukov? 3. Do you think you would react to imprisonment more like Pilgrim or Shukov? Why? a. Is your reaction the result of your nationality? Your temperament? Your expectations of life? 4. What do you find to be the most stunning aspect of the article? Quote the text and explain. X. Topic: Cold War on Film: The Satire of Strangelove Text: Dr. Strangelove. Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Dir. Stanley Kubrick. Perf. Peter Sellers, George C. Scott. Sony Pictures, 1964. S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 14 Flanigan, Literature of War Thematic Tie: Satire that Binds (Film, American) Time: (40 min, 5 classes) Objectives: 1. Controversy surrounding film when first released 2. United States Air Force Disclaimer: Why needed? 3. Popular view, 1960s, of American and Soviet Relations; Cold War 4. Satire in film versus satire of novel 5. “…literary art of diminishment for the purpose of reform…” 6. As much as an indictment of America as of Russia 7. Explores common stereotypes, misconceptions 8. Special emphasis placed on “tag names” 9. Strangelove’s inability to extricate himself from the past 10. Suggestions about the shallowness of the human condition, despite nationality 11. Issues of MAD: Mutually Assured Destruction 12. Basis in reality? Conspiracy theories? 13. Continue tie to contemporary political discussion about nuclear disarmament, post-Cold War Assessment: In-class viewing, study guide, character guide, recall quiz Study Guide: 1. For an excellent study guide, refer: [http://nd.edu/~dlindley/handouts/strangelovenotes.html] Author: Dan Lindley [Should you like an idea in here, be sure to give credit to the author!) Recall Quiz 1. Students take notes during film. Explain that each student will design his own recall quiz containing twenty short-answer questions. This assignment counts as homework. Following, cull the thirty best questions for class quiz. Take Home Essay: 1. What is satire? Stanley Kubrick’s film, Dr. Strangelove, is considered a satirical film. Why? Where is Kubrick’s employment of satire most successful? Be specific. S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 15 Flanigan, Literature of War XI. Topic: It’s Nothing Personal: The Gang Mentality of War Text: Greene, Graham. “The Destructors.” Arp 111-125. Thematic Tie: The Impersonality of Conflict on Massive Scale (Short Story, British) Time: (40 min, 2 classes) Objectives: 1. Establish connection to Greene’s Brighton Rock; another example of gang mentality 2. Landscape of bombed London; landscape as metaphor 3. How do children find “play” in rubbish? Ruins as visual metaphor, constant reminder 4. Exchange (stealing?) of power in gang; Trevor vs. Blackie 5. How do we choose victims for violence? How do we establish distance? 6. How do we justify our actions with or without political ideology to uphold? 7. Laughter and Irony / Dénouement proves especially problematic / Why? 8. Do we comfort the “causalities” of war? Do we have a moral responsibility? 9. Draw parallels to “War on Terror” Assessment: Homework reading, recall questions, reading quiz, blog Reading Quiz: 1. The story begins on the eve of what holiday? [August Bank Holiday] 2. What famous architect is mentioned near the opening of the narrative? [Wren] 3. What does Mr. Thomas give to the boys? [Chocolate] 4. How old is the home belonging to “Old Misery”? [200 years] 5. What is T’s full name? [Trevor] 6. What does he go by a single initial? [Embarrassed by his social class] 7. How many boys are in the gang at the time of destruction? [12] 8. Mike states that he might be late. Where does Mike “have to go”? [Church] 9. Where does Mr. Thomas get stuck? [Loo] 10. Complete this phrase: “There’s nothing _____, but you’ve got to admit it’s funny.” [Personal] Blog: 1. State and fully support a theme for Graham Greene’s short story “The Destructors.” S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 16 Flanigan, Literature of War XII. Topic: What do We Want? For What are We Hunting? Text: Wolff, Tobias. “Hunters in the Snow.” Arp 86-99. Thematic Tie: Pursuit of Happiness for All Peoples: Inevitable Misdirection (Short Story, American) Time: (40 min, 2 classes) Objectives: 1. Physical landscape as metaphor for internal landscape; link to Chekhov’s “Gooseberries” 2. How do characters function as symbols? 3. Explore entire narrative as allegory 4. Link to seven deadly sins = Who embodies what? 5. Spiritual questions about restraint? Keeping desire in check? Historical implication in terms of power? 6. How do we deal with peoples and cultures that are driven by desires we do not recognize? 7. Who makes the “wrong turn” at the narrative’s conclusion? How long ago was the mistake made? 8. Is narrative propelled by an “easy understanding” of The American Dream? 9. Set up: Narrative as perfect analog to Kochergin’s “A Potential Customer” 10. Concentrate on hunting, weapons, weather, “game” as both verb and object Assessment: Homework reading, recall questions, reading quiz, roundtable discussion Reading Quiz: 1. At the opening of the narrative, who is waiting? [Tub] 2. Who is the author of the story? [Tobias Wolff] 3. Who is involved with the babysitter? [Frank] 4. What does Frank have engraved onto his ring in diamonds? [F] 5. Who shoots at the fence post and tree? [Kenny] 6. Who shoots Kenny? [Tub] 7. Distance wise, how far away is the nearest hospital? [50 miles] 8. What does Tub forget at the bar? [Directions to hospital] 9. In the roadhouse, what does Frank encourage Tub to do? [Eat pancakes] S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 17 Flanigan, Literature of War 10. Complete this phrase from the last line: a. “They had taken a different ____________ a long way back.” [Turn] Roundtable Discussion: 1. One might argue that Tobias Wolff’s short-story, “Hunters in the Snow,” is an allegory. What is an allegory? Do the structural elements of “Hunters in the Snow” qualify the work as allegory? Cite the text. XIII. Topic: Easy Come, Easy Go: Hunting for Love Text: Kochergin, Ilya. “A Potential Customer.” Rasskazy: New Fiction From a New Russia. Eds. Mikhail Iossel, et al. New York: Tin House Books, 2009. 33-61. Thematic Tie: Comparative Tie to Wolff’s “Hunters in the Snow” (Short Story, Modern, Russian) Time: TBD (40 min, 2 classes) Objectives: 1. Is this the version of The Russian Dream? Is this just a young man’s dream? 2. Concentrate: hunting, weapons, weather, game, and nomadic quality of protagonist 3. “…my culture is underdeveloped…” Video game: Contemporary self-indictment 4. Is this more Vonnegut or Solzhenitsyn? 5. For what is the young man hunting? For what is the young woman? Who has settled? 6. Analyze issues of “domesticity” and “wildness” as displayed in modern Russia 7. Contrast the difficulty of obtaining a fire-arm in Russia versus relative ease in America 8. Explore: What is protagonist’s relationship to his past? His distant past? His immediate past? Assessment: In-Class Reading; language is difficult Blog: 1. Consider the passage and answer one of the following questions: a. “From the telephone exchange, I called Moscow. Then I went onto the street, had a smoke, and reflected that I had barely known what to say. I heard Olka’s voice, and answered something. That’s to say I told her what I was expected to, but couldn’t adequately explain what I was feeling now. Oh she probably wouldn’t S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 18 Flanigan, Literature of War have really understood. I decided to try and describe it in a letter. I’d start writing when I arrived” (59). i. What is he “expected” to say? ii. What do you think he is actually “feeling?” iii. Based on your understanding of the story, would Olka “understand” his feeling? iv. Do you think he will write the letter? Why or why not? XIV. Topic: Pop, Pop, Pop Music: Contemporary Russian Fiction! The Dog is Named Denisovich Text: Zobern, Oleg. “Bregovich’s Sixth Journey.” Rasskazy: New Fiction From a New Russia. Eds. Mikhail Iossel, et al. New York: Tin House Books, 2009. 63-68. Thematic Tie: Portrait of The Russian as A Modern, Young Man (Short Story, Modern, Russian) Time: (40 min, 2 classes) Objectives: 1. Brief biography on Zobern 2. Brief biography on Bregovich; Youtube.com videos of his playing 3. Reliable, first-person narrator? 4. Young life in Modern Russia: concentration on Krasnodar and Moscow 5. Significance of naming the dog “Ivan Denisovich” 6. Is the naming homage or an insult? How do we know? 7. Connection to Vonnegut’s employment of “dogs” in Slaughter-House Five 8. How does narrative insist on the passing of history? 9. How do modern Russians feel about their past? 10. Does Zobern realize Solzhenitsyn’s message, about art specifically, as delivered in his Nobel Speech? 11. How do music and life relate? 12. If time, explore some of the poets named by narrator, especially the exalted Assessment: Journal Questions Journal Questions: Answer one of the following: S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 19 Flanigan, Literature of War 1. What aspects of the narrative seem particularly modern? 2. If you had to choose one musician/composer whose work best “speaks” to your life, who would you choose? Why? Roundtable Discussion: (Preparation for midterm exam) 1. Define tone. What is the tone of Oleg Zobern’s short story, “Bregovich’s Sixth Journey”? Recall that Zobern born was born in 1980; he is a young Russian writer. He was only 11 when The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) collapsed. Why does the narrator rename his neighbor’s dog “Ivan Denisovich”? What does the short story reveal about contemporary Russian’ attitudes towards the past? Towards the future? XV. Topic: Meaning is Not Happiness: “Do Good!”: Chekhov’s Hero Text: Chekhov, Anton. “Gooseberries.” Arp 202-211. Thematic Tie: Traditional Russian Fiction (Short Story, Russian) Time: (40 min) Objectives: 1. Brief biography on Chekhov; photographs from museum; PowerPoint presentation 2. Landscape in relation to weather 3. Connections between “descriptive, external geographies” and “internal dispositions” of characters 4. Explore the format of the frame story 5. Discuss the processes of traditional Russian “naming”: Given, Patronymic, Surname 6. Biographical lens: Circumstances in Chekhov’s life and career in 1898 7. “Water” as recurring symbol; “baptism,” “Christian influence” 8. Possible: Journaling on weather’s affect on mood and disposition? 9. Comparison of weather in the United States and Russia; easy link to respective settings in both Vonnegut and Solzhenitsyn Assessment: Homework, recall questions, reading quiz Reading Quiz: 1. Describe the weather at the opening of the narrative. [Overcast] 2. Does Aliokhin live upstairs or downstairs? [Downstairs] 3. What does Aliokhin insist he do before entertaining his friends? [Bathe] S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 20 Flanigan, Literature of War 4. Which brother is older: Ivan or Nicholai? [Ivan] 5. What does Nicholai most desire? [His own gooseberry-bush] 6. What odor wafts through the air at the story’s conclusion? [Tobacco smoke] 7. Who is the author of the story? [Chekov] 8. Who is Pelagueya? 9. In what year was the story published? [1898] 10. Do Aliokhin and Bourkin enjoy Ivan’s story about his brother? [No] XVI. Topic: Class Struggle: Keeping Up Appearances Text: Kozlov, Vladimir. “Drill and Day Song.” Rasskazy: New Fiction From a New Russia. Eds. Mikhail Iossel, et al. New York: Tin House Books, 2009. 97-104. Thematic Tie: Companion Text to “Out, Out— .” (Short Story, Modern, Russian) Time: (40 min, 2 classes) Objectives: 1. Is this return of: “So it goes”? 2. Matter-of-factness in the face of death; refusal to implicate self 3. Questions of class? 4. Explore the importance of “appearances”: Why must they outweigh the actuality of the event? 5. How does the stress on appearance tie to the incessant propaganda of Soviet times 6. Explore the title: Why does it not even “hint” at the young boy’s passing? 7. What is the narrator’s role in the boy’s death? 8. Is there responsibility? If so, with whom does it reside? Why? Assessment: Blog Blog: 1. As a literary critic, evaluate the literary merit of the short story. Draw on your understanding of narrative structure and Russian literature. In short, pull out all the stops! Time to shine. Allusions to other texts within this unit are highly encouraged. XVII. Topic: No More to Build on There: The Power of the Present Moment Text: Frost, Robert. “Out, Out—.” Arp 779. S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 21 Flanigan, Literature of War Thematic Tie: Companion Text to “Drill and Day Song” (Poem, American) Time: (40 min) Objectives: 1. Transition from unit to formal unit on poetry 2. Link to Kozlov’s resignation, matter-of-factness about death 3. Link to Vonnegut’s ironic resignation 4. Special attention paid to language, meter, image in terms of foreshadowing 5. Remind students that Russian stories are translations; poem is, for most, the native tongue 6. Explore title’s allusion to Shakespeare’s Macbeth? 7. What can be said about literature’s ability to link the past to the present? Texts: Required: Arp, Thomas R. and Greg Johnson, eds. Perrines’s Literature, Sound, and Sense. United States: Thomson and Wadsworth, 2006. Supplementary: Chekhov, Anton. “Gooseberries.” Arp 202-211. Dr. Strangelove. Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Dir. Stanley Kubrick. Perf. Peter Sellers, George C. Scott. Sony Pictures, 1964. Frazier, Ian. “On the Prison Highway; Our Far-Flung Correspondents.” The New Yorker Aug. 2010: 28. Frost, Robert. “Out, Out—.” Arp 779. Greene, Graham. “The Destructors.” Arp 111-125. Kochergin, Ilya. “A Potential Customer.” Rasskazy: New Fiction From a New Russia. Eds. Mikhail Iossel, et al. New York: Tin House Books, 2009. 33-61. Kozlov, Vladimir. “Drill and Day Song.” Rasskazy: New Fiction From a New Russia. Eds. Mikhail Iossel, et al. New York: Tin House Books, 2009. 97-104. Owen, Wilfred. “Dulce et Decorum Est.” Arp 651-652. Wolff, Tobias. “Hunters in the Snow.” Arp 86-99. Smith, Dinitia. “Kurt Vonnegut, Novelist Who Caught the Imagination of His Age, Is Dead at 84.” New York Times 12 April 2007. P1 S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 22 Flanigan, Literature of War Solzhenitsyn, Alexander. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. New York: Signet Classic, 1963. __________. “Nobel Lecture.” NobelPrize.org. 2010. <http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1970/solzhenitsyn-lecture.html> Thurber, James. “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” Zoetrope: All Story. 2010. <http://www.all-story.com/issues.cgi?action=show_story&story_id=100> Tolstoy, Leo. “The Three Hermits.” Short Shorts: An Anthology of the Shortest Stories. Eds. Irving Howe, et al. New York: Bantam Book, 1982. 3-10. Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughter-House Five. New York: Dell Publishing, 1966. Yeats, William Butler. “An Irish Airman foresees His Death.” Bartleby: Great Books Online. 2010. < http://www.bartleby.com/148/3.html> Zobern, Oleg. “Bregovich’s Sixth Journey.” Rasskazy: New Fiction From a New Russia. Eds. Mikhail Iossel, et al. New York: Tin House Books, 2009. 63-68. S Flanigan, Fulbright-Hays Study Tour, Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies, University of Michigan ◊ Page 23 Hi Sean! Day before yesterday I found in my mail box (not in an electronic but real) a post card from Rachel, it was so nice! Especially i didn't receive such cards so many years from anybody (except landlord company or fees department etc). Please say Rachel my good words for it. How are you Sean? How is the weather in Baltimor? here in Krasnodar is very nice now +27 and a lot of grape vine this year. Be well. Y.