International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014

Vol. 2, No.1, 63-73

URL: http://www.pakinsight.com/?ic=projournal&journal=IPSBS

NURSE STAFFING: A CONCEPT ANALYSIS

Ying Liu

Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University Bangkok, Thailand, School of Nursing, Dalian

Medical University, Dalian city, China

Yupin Aungsuroch

Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

Ping Jiang

School of Nursing, Dalian Medical University, Dalian city, China

Feng Ge Wang

The People’s Hospital of Baoan, Shenzhen city, China

ABSTRACT

This study aims to undertake a concept analysis of nurse staffing. Research studies show that nurse

staffing would have a significant impact on nurse, patient and hospital outcomes. However, a

theoretical definition of what exactly “nurse staffing” means is not clear. Therefore, Walker and

Avant's approach of concept analysis is used. Dictionaries, books, theses/dissertations, research

articles from Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Science direct,

PubMed, and Google Scholar databases were applied to search concept analysis topics in the

process. The result shows that the main attributes of nurse staffing are (1) nurses’ quantity and (2)

nurses’ quality. The antecedents of nurse staffing include demand factors and supply factors. The

consequences of nurse staffing have an essential impact on nurse, patient, and hospital outcomes.

This analysis provides nurse managers with a new perspective to look at nurse staffing, which does

not only consider the number of nurses, but also the qualification of nurses. These results may

further influence health policy makers to consider both quantity and quality of the global nursing

shortage.

What is already known about this topic?

-Nurse staffing significantly impacts nurse, patient, and hospital outcomes.

What this paper adds?

-The attributes of nurse staffing include two main attributes, which are nurses’ quantity and

nurses’ quality.

-The demand and supply model is used to explain the factors influencing the antecedents of nurse

staffing within the current global situation.

-The conceptual model of nurse staffing gives the health policy maker a clear picture of the

attributes, antecedents, consequences, and empirical indicators pertaining to nurse staffing.

© 2014 Pak Publishing Group. All Rights Reserved.

KEYWORDS: Concept analysis, Nurse staffing, Outcome, Attribute, Antecedent, Consequence,

Case, Empirical indicator

INTRODUCTION

In the examination of the global health workforce crisis, World Health Report stated that the

most critical issue facing health care systems nowadays is the shortage of the people who make

them work (World Health Organization, 2003). In 2006, the World Health Organization (WHO)

devoted the whole World Health Report to analyzing the negative impact of human resource

shortages on global health care (World Health Organization, 2006). Based on these estimates, it

foresees that there are 57 countries with critical shortages equivalent to a global deficit of 2.4

million doctors, nurses, and midwives.

In health care organizations, nurses are the major profession. A nursing shortage is being

experienced across virtually all westernized healthcare systems, including the USA (World Health

63

International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 2(1): 63-73

Organization, 2008) and Canada (Spurgeon, 2000), with the same situation existing in far eastern

countries such as China. According to the WHO report (World Health Organization, 2008), close to

a million professional nurses will be needed by 2020 in the United States of America. In China,

according to the Chinese national nursing career development outline (Ministry of Public Health,

2012), at the end of the 2015, 2,860,000 nurses are needed due to an increasing demand of the

population. Until 2011, there were 2,233,000 registered nurses in China. Thus, there are still

627,000 vacant nursing positions that need filling in order to achieve the minimum required

number of registered nurses (RNs).

An increasing body of evidence indicates that adequate nurse staffing is required for patient

safety and to justify nursing resource allocations. Several staffing variables are found that are

associated with nurse, patient, and hospital outcomes. For example, the empirical studies support

the idea that adequate nurse staffing is related to a nurse‟s positive perception of job satisfaction

(Davidson et al., 1997; Shaver and Lacey, 2003; Dunn et al., 2005) and reduced nurses‟ burnout

(Aiken et al., 2002; Sheward et al., 2005). Moreover, nurse staffing variables have also been

reported to influence patients‟ mortality (West et al., 2009), pressure ulcers (Yang, 2003), failureto-rescue (Halm et al., 2005), and patient satisfaction (Seago et al., 2006; Tervo-Heikkinen et al.,

2008). Furthermore, it is found that nurse staffing variables significantly impact hospital outcomes,

such as nurse-assessed quality nursing care (Rafferty et al., 2007), personal cost per patient day

(Thungjaroenkul et al., 2008), and a patient‟s length of stay (LOS) (Tschannen and Kalisch, 2009).

In the empirical staffing research, some authors used the term skill mix, while some authors used

patient to nurse ratio or hours per patient day (HPPD). In addition, the term full time equivalent

(FTE), nurses‟ education, nurses‟ experience, and nurses‟ perceived staff adequacy are also found

in nurse staffing studies. Manojlovich and Sidani stated that the majority of staffing studies “gave

little explanation for why a specific staffing variable was chosen over others” (Manojlovich et al.,

2011). Since the definition of nurse staffing is not clear, the theoretical definition of nurse staffing

should be determined through conceptualizing the attributes of this concept. Then, the empirical

indicators that reflect these concept attributes would be beneficial for measuring this concept.

Therefore, the aim of this analysis is to determine the attributes, antecedences, consequences, and

empirical indicators of nurse staffing by using Walker and Avant‟s concept analysis process.

METHODS

This paper defines the attributes of nurses staffing using the eight-step Walker and Avant

process of concept analysis method: (1) select a concept; (2) determine the purpose of the analysis;

(3) identify all uses of the concept; (4) determine the defining attributes; (5) construct a model case;

(6) construct a borderline, related, and contrary case; (7) Identify antecedents and consequences;

and (8) Define empirical referents. The main objectives of the concept analysis process are to

identify the attributes and provide researchers with a precise definition of the concept. Thus, this

analysis could provide the conceptualized definition and the aforementioned concept analysis

process contents of nurse staffing. Dictionaries, books, theses/dissertations and research articles,

which cover the year from 1994 to 2014, were reviewed. A total of 51 articles were used for this

analysis.

RESULT

In accordance with Walker and Avant‟s concept analysis process (Walker and Avant, 2005),

the results of the definitions, attributes, case descriptions, antecedents, consequences, and empirical

referents related to nurse staffing have been written in this part.

A. Definitions Related to Nurse Staffing

1) Dictionary Definitions of Nurse

“Nurse staffing” does not appear in dictionaries as one term. Since the word “staffing” does

not appear in the following dictionary, the word “nurse” was first reviewed.

According to Collins English Dictionary & Thesaurus‟s description, nurse is “a person, often a

woman, who is trained to tend the sick and infirm, assist doctors” (Summers and Holmes, 2006).

64

International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 2(1): 63-73

Cambridge dictionary of American English states nurse is “a person trained to care for people who

are sick or not able to care for themselves because of injury or old age, and who may also help

doctors in treating people” (Landau, 2000). Similarly, the New Oxford American Dictionary

defines the word “nurse” as “a person trained to care for the sick or infirm, esp. in a hospital”

(Jewell and Abate, 2001). Moreover, Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary defines nurse as a

noun in two ways “one that look after, fosters, or advises” and “a person who is skilled or trained in

caring for the sick or infirm especially under the supervision of a physician” (Merriam-Webster's

Collegiate Dictionary, 1998).

2) The Definitions of Staffing

The business dictionary defines staffing as “the selection and training of individuals for

specific job functions, and charging them with the associated responsibilities” (Business

Dictionary). In the management discipline, Heneman III et al. (2011) defines staffing as the process

of deploying, acquiring, and retaining a workforce of sufficient quantity and quality to create

positive impacts on the organization‟s effectiveness. In the science industry, Plott et al. defines

staffing as the accurate number of people with the available abilities and skills to support factory

events and operations (Plott et al., 2006).

3) Literature Definition of Nurse Staffing

In literature cited here, the following research has discussed nurse staffing. For example,

Douglass (1988) and Sullivan and Decker (1997) define nurse staffing as a process of determining

and allocating an appropriate amount and mix of nursing personnel to fulfill positions in nursing

organizations and units. Similarly, Yoder-Wise mentions nurse staffing as “the function of planning

for hiring and allocating qualified nurses‟ resources to meet the needs of patients for care and

services” (Yoder-Wise, 2003). Sullivan and Decker define nurse staffing as providing suitable

numbers and categories of nurses in order to make nursing care efficient and effective (Sullivan and

Decker, 2005). Nurse staffing is also defined as “the process used to determine and deploy the

acceptable number and skill mix of personnel needed to meet the care needs of patients in a

program, unit or healthcare setting” (Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, 2006).

Similarly, nurse staffing refers to “the number and type of workers employed by an agency to

provide nursing care to the persons served by the agency” (Fitzpatrick and Wallace, 2006). In

addition, Nantsupawat defines nurse staffing as the number of patients cared for by one nurse in a

nursing unit (Nantsupawat, 2010).

B. Attributes or Characteristics of Nurse Staffing

Walker and Avant define attributes as the characteristics that appear in a concept repeatedly,

and help researchers differentiate the occurrence of a specific phenomenon from a similar one

(Walker and Avant, 2005).

From the aforementioned definitions, two main characteristics of nurse staffing are

synthesized: nurses‟ quantity and nurses‟ quality. Nurses‟ quantity refers to the adequate number of

nurses that provide nursing care. Nurses‟ quality refers to nurses‟ skills to provide the nursing care,

such as type/category or skill mix of nurses.

C. Cases Description and Analysis for Nurse Staffing

The model case, borderline case, related case, and contrary case are demonstrated in this

analysis. Walker and Avant (2005) state that (1) a model case demonstrates “all defining attributes

of the concept” (p.69); (2) a borderline case contains “most of the defining attributes of the concept

being examined but not all of them” (p.70); (3) a related case demonstrates “ideas that are very

similar to the main concept but that differ from them when examined closely” (p.71); and (4) a

contrary case is a “clear example of not the concept”(p.71). Examples of each of the three types of

cases are provided below.

1) Model Case

Hospital A was a remarkable hospital. It attracted competent nurses to work there. The nurse to

patient ratio was 1:4. According to the number of patients in one unit, twelve RNs worked as full65

International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 2(1): 63-73

time workers (40 hours per week, 52 weeks one year). Three RNs worked as part-time workers (20

hours per week, 52 weeks one year). Additionally, two licensed practical nurses (LPNs), under an

RN‟s supervision, worked as full-time workers. The human resource department manager

calculated FTE for RNs in this unit was 40×52×12+20×52×3=28080. The FTE for LPNs was

40×52×2=4160. Additionally, nurses‟ tasks were allocated according to nurses‟ work experience

and educational background. HPPD was documented electronically according to the type of nurses,

such as RNS or LPNS. In addition, from the hospital survey, it also found that nurses reported that

this hospital did have enough nurses to provide qualified patient care.

This model case illustrates the successful achievement of all the attributes of the nurse staffing

concept. First, nurses‟ tasks were allocated regarding their education and experience. The

categories of nurses in this ward included both RNs and LPNs. Therefore, the nurse staffing

attribute of nurses‟ quality was achieved. Second, FTE was used to measure nursing workforce in

the ward. HPPD, nurse-patient ratio, and nurse perceived staffing adequacy were included in this

case as well. Thus, the attribute of nurses‟ quantity did exist.

2) Borderline Case

Hospital B was a tertiary general hospital. The nurse to patient ratio was 1:6. Additionally, the

nursing tasks were allocated according to nurse work experience and educational background as

well. In one inpatient ward, three LPNs were under RNs supervision. Moreover, by using the

hospital documentation system, HPPD was documented according to the type of nurses.

In this case, not all nurse staffing attributes appeared. The attribute of nurses‟ quality was

included, since the nurses‟ education, nurses‟ experience, and skill mix were mentioned in this

case. However, the attribute of nurses‟ quantity was lacking because FTE and nurse perceived

staffing adequacy were not recorded in the case.

3) Related Case

Hospital C was a tertiary general hospital. This hospital recruited nurses from the formal

nursing schools. New nurses took part in the department rotation during the beginning of three

years‟ work in order to get a variety of work experience. In one unit, the RN to LPN ratio was 5:1.

According to the number of patients in this unit, eight RNs worked as full time workers (40 hours

per week, 52 weeks one year). Two RNs worked as part time workers (20 hours per week, 52

weeks one year). Additionally, two LPNs were supervised by a RN and worked as full time

workers. The human resource department manager calculated the FTE for RNs in this unit as

40×52×8+20×52×3=19760. The FTE for LPNs was 40×52×2=4160. HPPD was documented

electronically regarding the type of nurses, such as RNS or LPNS. In addition, this unit also used the

HPPD system and the nurse to patient ratio was 1:8. Since there were enough nurses working in

this unit, the average number of LOS was seven days. This related case illustrated the successful

achievement of all attributes of the nurse dose concept, which includes the attributes of purity,

amount, frequency, and duration. Nurses‟ education and experience reflected the purity attribute.

The FTE was described as the amount attribute. The HPPD and nurse to patient ratio represented

the frequency attribute. The LOS was used to explain the duration attribute.

4) Contrary Case

In one private clinic, RNs tasks were allocated depending on how many patients visited the

clinic. The clinic manager did not calculate the nurse workforce requirement by using FTE. Thus,

nurses had flexible work schedules in accordance with the actual clinic situation.

In this case, all attributes of nurse staffing had absented. First, neither nurses‟ education,

nurses‟ experience, or skill mix were introduced. Therefore, the attribute of nurses‟ quality was not

maintained. Second, FTE, HPPD, nurse to patient ratio, or nurse perceived staffing adequacy were

not mentioned in this case as well, thus causing the attribute of nurses‟ quantity to be lacking.

D. Antecedents of Nurse Staffing

“Antecedents are those events or incidents that must occur prior to the occurrence of the

concept” (Walker and Avant, 2005). Sources show that the factors that influence nurse staffing can

be divided into two groups: demand factors and supply factors.

66

International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 2(1): 63-73

1) Demand Factors Influence Nurse Staffing

The following factors are related to the demand side: (1) the increasing aging population with a

shift from hospital to home care service (Booth, 2002; Oulton, 2006), (2) spreading of infectious

disease, such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis (Oulton, 2006), (3) patient diagnosis or conditions

(Pay et al., 1996).

A) The Increasing Aging Population with a Shift from Hospital to Home Care Service

Several researchers have stated that an increasing aging population causes an increase in the

number of nurses (Booth, 2002; McCatheon, 2006; Oulton, 2006). Since advances in science and

medicine result in a decreased death rate and an increased life expectancy (Guo, 2008), people live

longer than before. For example, in the United States, the recent census reports that nearly 35

million individuals were 65 and older, approximately one in eight Americans. By 2030, one in five

Americans will be older than 65 (Himes, 2002). Similarly, in China, the older adult population is

143 million, comprising 20% of the older adult population in the world (Wang, 2004). It is

estimated that the older adult population in China is increasing at a rate of 3.2% per year; therefore,

by 2020, the proportion of older adults will be increased to 16% (China Sustainable Development

Insituition, 2000) and by 2040, older adults will comprise over 27% of the national population in

China (Populiation Council, 2005). Under this situation, more nurses will be required to provide

nursing service for the aging population.

B) Infectious Disease, Such As HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis

According to the literature reviewed, it has been mentioned that infectious diseases, such as

HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis cases, will increase the need of nurses as well (Oulton, 2006), since the

number of people living with those infectious diseases has increased dramatically. For example, the

number of people living with HIV rose from an estimated 29.5 million in 2001 to 33 million in

2007 (United Nations, 2008). In addition, the tuberculosis incidence rate increased its distribution

from 1.35 million in 2004 to 18 million in 2006. In 2006, there were an estimated 1.7 million

deaths due to tuberculosis and 14.4 million people were infected with the disease (United Nations,

2008). Therefore, more nurses with specialized training in taking care of infectious disease patients

are needed as well.

C) Patient Diagnosis or Conditions

Patient diagnosis or conditions also influenced nurse staffing. For example, Pay et al. (1996)

surveyed 12 home care agencies in Massachusetts to report the home health resource use in patients

with different diagnoses. The results found that, during a period of one year, AIDS patients

required 33.3 home visits, infants and pregnant women required 25.1 home visits, and medicalsurgical patients required a mean of 8.1 home visits. Additionally, Brooten et al. (2001) conducted

randomized clinical trials to provide prenatal care and home follow-up to women with high-risk

pregnancies. Women with progestational diabetes required the highest mean number of contacts

(M=109.8, SD=47.86), followed by women with chronic hypertension (M=99.8, SD=29.65),

women at risk of preterm labor (M=84.5, SD=33.65), women with gestational diabetes (M=64.5,

SD=27.09), and women with diagnosed preterm labor (M=54.8, SD=20.99). Therefore, the

allocation of nurses should also consider the patients‟ diagnoses or conditions.

2) Supply Factors Influence Nurse Staffing

Factors that influence nurse staffing on the supply side include the following aspects: (1)

legislation (Spetz et al., 2000); and (2) work environment factors (Booth, 2002; Goodin, 2003;

McCatheon, 2006; Oulton, 2006; American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2009).

A) Legislation

Legislation is one of the factors that influence nurse staffing. According to Spetz, Seago,

Coffman, Roseneff, and O'Neil‟s report (Spetz et al., 2000), in order to maintain patient safety, the

California legislation requires a ratio of one nurse to six medical surgical patients, one to four

pediatric patients, one to four mother-baby couples, one to two laboring patients, and one to one for

67

International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 2(1): 63-73

trauma patients. However, in other countries, this ratio may vary according to each country‟s

situation.

B) Work Environment Factors

A good working environment attracts and retains nurses to continue working at the current

place. Censullo (2008) explained that a reputation of having a poor working environment serves as

a deterrent to new recruits and disheartens even tenured nurses. Turnover at an organizational level

is seen to be a major contributor to the number of nurses (Gauci-Borda and Norman, 1997).

According to many sources, working environment has been found to significantly influence

nurses‟ intention to leave (Gardner et al., 2007; Hwang and Chang, 2009), which further

contributes to turnover (Davidson et al., 1997). In addition, other factors in the work setting, such

as job satisfaction (Shields and Ward, 2001; Larrabee et al., 2003) and workload (Aiken et al.,

2002) are also found to impact a nurse‟s intention to leave. Thus, work environment factors have a

correlating relationship with the number of nurses.

E. Consequences of Nurse Staffing

“Consequences are those events or incidents that occur as a result of the occurrence of the

concept” (Walker and Avant, 2005). The effect of nurse staffing would be on nurse outcomes,

patient outcomes, and hospital outcomes.

1) Nurse Staffing Impact on Nurse Outcomes

Research points out several studies that show that nurse staffing significantly influences nurse

job satisfaction, nurse burnout, intention to leave, nurse assessed quality of care, or adverse nurse

events. For example, Sheward et al. (2005) divided nurse to patient ratio into four levels, which

account as 0-4, 5-8, 9-12, to 13 or greater. When numbers of patients to nurses increase, risk of

emotional exhaustion (OR=0.57, 0.67, 0.80 to 1.00, P<0.01) and dissatisfaction with one‟s current

job (OR=0.70, 0.75, 0.84 to 1.00, P<0.01) increase as well. The consistent result is also supported

by Aiken et al. (2002), Aiken et al. (2007), Aiken et al. (2008), and Rafferty et al. (2007). In

addition, the increase of patients to nurses also impacts a nurse‟s intention to leave (Aiken et al.,

2007; Cho et al., 2009) and nurse-assessed quality of care (Rafferty et al., 2007; Aiken et al.,

2008).

In addition, other nurse staffing indicators, such as nurses perceived adequate staffing and a

nurse‟s experience are also found to impact nurse outcomes. For example, Cho et al. (2009)

research findings show that when nurses perceive adequate staffing, they are less likely to be

dissatisfied with their job, they tend to have low burnout, and have less intention to leave.

Gunnarsdottir et al. (2009) also found that nurse perceived adequate staffing is a predictor of nurse

job satisfaction, burnout, and nurse-assessed quality of care. Tervo-Heikkinen et al. (2009) states

that adequate staffing negatively influences adverse events for nurses (p = 0.004, b1 =-0.870, R2 =

24.6%). Halm et al. (2005) found that with every one year increase of employment, a nurse`s risk

of high emotional exhaustion will be increased by 5.2% (p = 0.01) and job dissatisfaction will be

increased by 6.8% (p = 0.03). Moreover, various nurse staffing indicators have been found to

influence nurse needle stick injuries. For example, Patrician et al. (2011) reported that factors of a

lower RNs skill mix, a lower percentage of experienced staff, and fewer HPPD associated with

needle stick occurrences on working shifts.

2) Nurse Staffing Impact on Patient Outcomes

According to the related research, it is found that nurse staffing influences several patient

outcomes, such as mortality (West et al., 2009), pressure ulcers (Yang, 2003), failure-to-rescue

(Halm et al., 2005), and patient satisfaction (Seago et al., 2006; Tervo-Heikkinen et al., 2008).

For example, Aiken et al. (2002) determined the association of patient-to-nurse ratio with

patient mortality, failure-to-rescue (deaths following complications). After adjusting for patient and

hospital characteristics (size, teaching status, and technology), each additional patient per nurse was

associated with a 7% (odds ratio [OR], 1.07; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03-1.12) increase in

the likelihood of dying within 30 days of admission and a 7% (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.11)

increase in the odds of failure-to-rescue.

68

International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 2(1): 63-73

In addition, various nurse staffing indicators have been found to influence patient satisfaction.

For instance, Tervo-Heikkinen et al. (2009) studied about patient satisfaction and the ratio and

structure of nurse staffing inpatient wards at four Finland university hospitals among 4045 patients.

The result showed that all six nurse staffing indicators significantly influenced some parts of the

patient satisfaction scores. These six nurse staffing indicators were skill mix (proportion of RNs out

of all nurses), patient-to-RN ratio in the day shift and in all shifts, patient load per RN, RN hours

per patient load, and working years in the same ward. The result showed that both staffing level

indicators and the patient-to-RN ratio in the day shift and in all shifts, were linearly connected to all

the sum scores, including the total satisfaction indicator. Quadratic correlation showed that when

the patient-to-RN ratio in the day shift increased to more than 8 patients per RN, satisfaction began

to decrease. Patient load per RN (month) was also statistically significant to the sum scores of

treatment, respect, and care of patient, participating in one‟s own care, adequate information, and

no problems with care, as well as the total satisfaction indicator (p ranged from <.001 to .012, b

ranged from −.312 to −.439 and R2 ranged from 18.0% to 38.3%). RN hours per patient load

positively influenced all satisfaction variables except social and physical welfare during the

hospitalization (p ranged from <.000 to .039). The regression coefficients (b) ranged from 3.961 to

6.084 and the total variance (R2 %) ranged from 12.6% to 34.1%.

In addition, Kane et al. (2007) systematic review with meta-analysis‟s report gave the

conclusion that an increasing in RN staffing has an impact on lowering hospital related mortality in

intensive care units (ICUs), surgical, and medical patients. The odds ratios for an additional full

time equivalent per patient day are 0.91, 0.84, and 0.94 with 95% confidence interval (CI),

respectively. An increase of 1 RN per patient day causes a decreased odds ratio of hospital acquired

pneumonia, unplanned extubation, respiratory failure, and cardiac arrest in ICUs and a lower risk of

failure-to-rescue for surgical patients at 0.70, 0.49, 0.40, 0.72, and 0.84 with 95% confidence

interval (CI), respectively.

3) Nurse Staffing Impact on Hospital Outcomes

In health care setting, patients‟ costs and length of stay are important to hospital management.

Therefore, since nurse staffing influences these variables, they are classified as hospital outcomes.

Thungjaroenkul et al. (2008) studied the effect of nurse staffing on the cost of care in adult

intensive care units at a 1400-bed university hospital in Thailand. The result indicates that a higher

average ratio of RNs to patients influenced an increased personal cost per patient day (HC) (b =

10.92, p <0.001) and the average ratio of RNs to other nursing staff positively impacted the HC (b

= 8.07, p<0.001).

Tschannen and Kalisch (2009) explored the predictor of nurse staffing variables to patient

length of stay (LOS). Three staffing variables were selected (HPPD, skill mix, and nursing

expertise) through surveys and administrative forms. The overall model accounted for 40.3% of the

variation noted by the deviation from expected LOS (p < .0001). Patients with a higher HPPD

value were discharged sooner than expected by their DRG (b = 2.459, p = .05).

F. Empirical Referents of Nurse Staffing

“Empirical referents are classes or categories of actual phenomena that by their existence or

presence demonstrate the occurrence of the concept itself” (Walker and Avant, 2005). The defining

attributes of the nurse staffing concept are abstract, so it needs empirical referents in order to make

the concept measurable. From previous explanation, nurse staffing included the attributes of (1)

nurses‟ quantity and (2) nurses‟ quality. The following section examines these referents in detail.

1) Empirical Indicators for Nurses’ Quantity

From literature review, four staffing variables served as empirical indicators for nurse staffing

quantity: HPPD, the nurse–patient ratio, FTE, and nurse perceived staffing adequacy. HPPD refers

to the number of hours of paid nurse time relative to the number of patient days (Finkler and

Kovner, 2000). For this indicator, some countries‟ systems measure it based on patient diversity,

complexity, and nursing tasks required (Twigg and Duffield, 2009). In addition, it can be measured

by categorizing total nursing HPPD, RN HPPD, or no-RN HPPD (Choi and Staggs, 2014). The

formula to measure this indictor is [the hours of day shift × the number of all kinds of nurse

69

International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 2(1): 63-73

personnel (registered nurses, technical nurses, practical nurses, and nurse aids) +the hours of

evening shift × the number of all kinds of nurse personal+ the hours of night shift × the number of

all kinds of nurse personnel] ÷ the number of patients at the time of 24:00 (Chitpakdee, 2006). The

nurse–patient ratio refers to the number of patients who are assigned to any one nurse in a nursing

unit for a particular shift (Manojlovich and Sidani, 2008). It can be measured by the item “How

many patients did you take care of in the last shift” (Aiken et al., 2002). FTE represents “fifty-two

40-hour work weeks of five 8-hour days, or 2,080 hours, the typical annual paid work time for a

full-time employee” (Fitzpatrick and Wallace, 2006). Therefore, each personnel FTE can be

calculated by the formula of FTE =40 hours per week×(52weeks-vacation weeks). Nurse

perceived staffing adequacy describes nurse perception of an adequate number of nurses providing

quality patient care (Lake, 2002). It can be measured by the item “Enough registered nurses to

provide quality patient care” (Lake, 2002).

2) Empirical Indicators for Nurses’ Quality

From the literature reviewed, three empirical indicators are used for interpreting the attribute of

nurses‟ quality: nurses‟ education, nurses‟ experience, and skill mix. (1) Nurses‟ education refers to

the “highest degree achieved”. (2) Nurses‟ experience are the years of experience within one‟s

current position, such as RN or LPN. (3) Skill mix, sometimes named as staffing mix, is defined as

„proportion of RNs, LPNs, and unit assistive personnel (UAPs) working on the unit for each

patient‟ (Tschannen and Kalisch, 2009). These empirical indicators can be measured by the

following questions: “What is your education level?” “How long have you worked as a nurse?”

“Which type of license do you have?” or “What is your position at work?”

DISCUSSION

This analysis gives nurses a more fundamental perspective on characteristics of nurse staffing.

The current global nursing shortage situation is not only related to the number of nurses, but also to

the qualification of nurses in dealing with complex diseases or an increasing in the aging

population. Thus, this article summarizes the main attributes of nurse staffing, including nurses‟

quantity and nurses‟ quality. In order to bring relief to the global nursing shortage situation, the

health care managers should consider recruiting more nurses along with providing continuing

nursing education to enhance clinical nurses‟ abilities. Many kinds of these cases are illustrated in

this analysis to describe the understood phenomena related to nurse staffing in the clinical setting.

Based on the demand and supply model, the antecedents of nurse staffing are analyzed under the

current global situation. For instance, with the increasing of the aging population and infectious

disease, health policy makers should provide specific training programs for clinical nurses in order

to enhance and update their knowledge and skills. In addition, the consequences of the nurse

staffing concept show the significant impact of nurse staffing on various outcomes. It can help

nurse practitioners to conduct the meta-analysis or to construct hypotheses in order to further

conduct research that produce more effective outcomes. Moreover, with respect to empirical

references, all of the indicators representing nurses‟ quality and nurses‟ quantity are illustrated.

This analysis provides the concrete information along with a linkage of various nurse staffing

indicators.

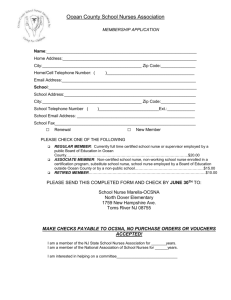

The conceptual model of nurse staffing (Fig.1) clarifies how antecedents, concept and

consequences of nurse staffing are related to each other. The findings of this analysis can be used to

provide service training for clinical nurses. This will ensure that nurses clearly understand the

nurse staffing concept. In addition, this model may further convince policy makers and clinical

nurse mangers to stipulate the nurse to patient ratio, the full time equivalent, and hire higher

educated nurses in order to achieve better nurse outcomes, excellent patient outcomes, and

expected hospital outcomes.

70

International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 2(1): 63-73

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported by the 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University,

Rachadapisek Sompote Fund. This research is under the support of the Liaoning Province

Education Science "Twelfth Five" plan research project (JG13DB196).

REFERENCES

Aiken, L.H., S. Clarke and D. Sloane, 2002. Hospital staffing, organization and quality of care: Cross-national

findings. Nursing Outlook, 50(5): 187-194.

Aiken, L.H., S.P. Clarke, D.M. Sloane, E.T. Lake and T. Cheney, 2008. Effects of hospital care environment

on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration, 38(5): 223-229.

Aiken, L.H., S.P. Clarke, D.M. Sloane, J. Sochalski and J.H. Silber, 2002. Hospital nurse staffing and patient

mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. The Journal of the American Medical Association,

288(16): 1987-1993.

Aiken, L.H., Y. Xue, S.P. Clarke and D.M. Sloane, 2007. Supplemental nurse staffing in hospitals and quality

of care. Journal of Nursing Administration, 37(7-8): 335-342.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2009. Nursing shortage fact sheet. Available from

http://www.aacn.nche.edu/Media/pdf/NrsgShortageFS.pdf.

Booth, R.Z., 2002. The nursing shortage: A worldwide problem. Rev Latino-am Enfermagem, 10(3): 392-400.

Brooten, D., J. Youngblut, L. Brown, S. Finkler, D. Neff and E. Madigan, 2001. A randomized trail of nurse

specialist home care for women with high-risk pregnancies: Outcomes and costs. American Journal

of Managed Care, 7: 739-803.

Business

Dictionary,

Online

business

dictionary.

Available

from

http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/staffing.html#ixzz39xQRDnaQ.

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, 2006. Staffing for safety: A synthesis of the evidence on

nurse

staffing

and

patient

safety.

Available

from

http://www.chsrf.ca/Migrated/PDF/ResearchReports/CommissionedResearch/staffing_for_safety_po

licy_synth_e.pdf.

Censullo, J.L., 2008. The nursing shortage: Breach of ideology as an unexplored cause. Advances in Nursing

Science, 31(4): E11–E18.

China Sustainable Development Insituition, 2000. The overview of aging people and continue development

situation. Available from http://www.cssd.acca21.edu.cn.

Chitpakdee, B., 2006. Nurses staffing, job satisfaction and selected patint outcomes. Chiang Mai, Thailand:

Chinag Mai University.

Cho, S.H., K.J. June, Y.M. Kim, Y.A. Cho, C.S. Yoo and S.C. Yun, 2009. Nurse staffing, quality of nursing

care and nurse job outcomes in intensive care units. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18: 1729 –1737.

Choi, J. and V.S. Staggs, 2014. Comparability of nurse staffing measures in examining the relationship

between RN staffing and unit-acquired pressure ulcers: A unit-level descriptive, correlational study.

Int. J. Nurs. Stud, 51(10): 1344-1352.

Davidson, H., P. Folcarell, S. Crawford, L. Duprat and J. Clifford, 1997. The effects of health care reforms on

job satisfaction and voluntary turnover among hospital-based nurses. Medical Care, 35: 634-645.

Douglass, L.M., 1988. The effective nurse leader manager. 3rd Edn., St. Louis: The C. V. Mosby.

71

International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 2(1): 63-73

Dunn, S., B. Wilson and A. Esterman, 2005. Perceptions of working as a nurse in an acute care setting.

Journal of Nursing Management, 13: 22-31.

Finkler, S.A. and C.T. Kovner, 2000. Financial management for nurse managers and executives. 2nd Edn.,

Philadelphia: Saunder.

Fitzpatrick, J.J. and M. Wallace, 2006. Encyclopedia of nursing research. 2nd Edn., New York: Springer

Publishing Company.

Gardner, J.K., L. Fogg, C. Thomas-Hawkins and C.E. Latham, 2007. The relationships between nurses'

perceptions of the hemodialysis unit work environment and nurse turnover, patient satisfaction, and

hospitalizations. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 34(3): 271-281.

Gauci-Borda, R. and I. Norman, 1997. Factors influencing turnover and absence of nurses: A research review.

International Journal of Nursing Studies, 34(6): 385–394.

Goodin, H.J., 2003. The nursing shortage in the United States of American: An integrative review of the

literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 43(4): 335-350.

Gunnarsdottir, S., S.P. Clarke, A.M. Rafferty and D. Nutbeam, 2009. Front-line management, staffing and

nurse-doctor relationships as predictors of nurse and patient outcomes. A survey of icelandic

hospital nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(7): 920-927.

Guo, Y.H., 2008. Implementing nurse regulation, protecting nurses' legal rights, and fulfilling nurses'

obligations. Available from http://www.cnabx.org.cn/Article_Show.asp?ArticleID=910.

Halm, M., M. Peterson, M. Kandels, J. Sabo, M. Blalock and R. Braden, 2005. Hospital nurse staffing and

patient mortality, emotional exhaustion, and job dissatisfaction. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 19(5):

241-251; quiz 252-244.

Heneman III, H.G., T.A. Judge and J.D. Kammeyer-Mueller, 2011. Staffing organization. 7 th Edn., USA:

McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Himes, C.L., 2002. Elderly Americans population reference bureau (Population Bulletin 56. No. 4, Population

Reference

Bureau).

Available

from

www.prb.org/Template.cfm?Section=PRB&template=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&C

ontentID=7021.

Hwang, J.I. and H. Chang, 2009. Work climate perception and turnover intention among Korean hospital staff.

International Nursing Review, 56: 73-80.

Jewell, E.J. and F. Abate, 2001. The new Oxford American dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kane, R., T. Shamlian, C. Mueller, S. Duval and T.J. Wilt, 2007. The association of registered nurse staffing

levels and patient outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Care, 45(12): 11951294.

Lake, E.T., 2002. Development of the practice environment scale of the nursing work index. Research in

Nursing & Health Sciences, 25(3): 176-188.

Landau, S.I., 2000. Cambridge dictionary of American english. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Larrabee, J.H., M.A. Janney, C.L. Ostrow, M.L. Withrow, G.R.J. Hobbs and C. Burant, 2003. Predicting

registered nurse job satisfaction and intent to leave. Journal of Nursing Administration, 33(5): 271283.

Manojlovich, M. and S. Sidani, 2008. Nurse dose: What's in a concept? Research in Nursing & Health

Sciences, 31: 310-319.

Manojlovich, M., S. Sidani, C.L. Covell and C.L. Antonakos, 2011. Nurse dose: Linking staffing variables to

adverse patient outcomes. Nursing Research, 60: 214-220.

McCatheon, A., 2006. Confronting the nursing shortage. Huber, D. L (Ed.), Leadership and nursing care

management. 3rd Edn., Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier.

Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 1998. Deluxe ed., Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

Ministry of Public Health, 2012. National nursing career development outline 2011-2015. Available from

http://www.moh.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/mohyzs/s3593/201201/53897.htm.

Nantsupawat, A., 2010. The predictive ability of the nurses' work enivronment and nurse staffing levels for

nurse and paient outcomes in public hospitals. Thailand, Chiang Mai, Thailand: Chiang Mai

University.

Oulton, J.A., 2006. The global nursing shortage: An overview of issues and actions. Policy, Politics, &

Nursing Practice, 7(3): 34S-39S.

Patrician, P.A., E. Pryor, M. Fridman and L. Loan, 2011. Needlestick injuries among nursing staff:

Association with shift-level staffing. American Journal of Infection Control, 39(6): 477-482.

Pay, S.M., C.P. Thomas, T. Fitzpatrick, H.L. Kayne and M. Abdel-Rahman, 1996. Home health resource use

by persons with AIDS, mothers and children and medical/surgical clients. Paper Presented at the

Association for Health Services Research Annual Meeting, Atlanta, GA.

Plott, C., A.M. Ronan, L. Laux, J. Bzostek, J. Milanski and S. Scheff, 2006. Identification of advanced human

factors engineering analysis, design and evaluation methods. 5th International Topical Meeting on

72

International Proceedings of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 2(1): 63-73

Nuclear Plant Instrumentation Controland Human Machine Interface Technology (NPIC and HMIT

2006).

Populiation

Council,

U.S.,

2005.

Social

science.

Aging.

Available

from

http://www.popcouncil.org/socsci/aging.html.

Rafferty, A.M., S.P. Clarke, J. Coles, J. Ball, P. James and M. McKee, 2007. Outcomes of variation in hospital

nurse staffing in english hospitals: Cross-sectional analysis of survey data and discharge records.

International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(2): 175-182.

Seago, J.A., A. Williamson and C. Atwood, 2006. Longitudinal analyses of nurse staffing and patient

outcomes: More about failure to rescue. Journal of Nursing Administration, 36(1): 13-21.

Shaver, K. and M.L. Lacey, 2003. Job and career satisfaction among staff nurses. Journal of Nursing

Administration, 33: 166–171.

Sheward, L., J. Hunt, S. Hagen, M. Macleod and J. Ball, 2005. The relationship between UK hospital nurse

staffing and emotional exhaustion and job dissatisfaction. Journal of Nursing Management, 13: 51–

60.

Shields, M. and M. Ward, 2001. Improving nurse retention in the national health service in England: The

impact of job satisfaction on intention to quit. Journal of Health Economics, 20: 677-701.

Spetz, J., J.A. Seago, J. Coffman, E. Roseneff and E. O'Neil, 2000. Minimum nurse staffing ratios in

California acute care hospitals. San Francisco, CA: Center for the Health Professions.

Spurgeon, D., 2000. Canada faces nurse shortage. British Medical Journal, 320: 1030.

Sullivan, E.J. and P.J. Decker, 1997. Effective leadership and management in nursing. California: AddisonWesley.

Sullivan, E.J. and P.J. Decker, 2005. Effective leadership and management in nursing. 6th Edn., Houston:

Pearson Prentice Hall.

Summers, E. and A. Holmes, 2006. Collins english dictionary & thesaurus. 4th Edn., Glasgow: HarperCollins

Publishers.

Tervo-Heikkinen, T., V. Kiviniemi, P. Partanen and K. Vehvilainen-Julkunen, 2009. Nurse staffing levels and

nursing outcomes: A bayesian analysis of finnish-registered nurse survey data. Journal of Nursing

Management, 17(8): 986-993.

Tervo-Heikkinen, T., P. Partanen, P. Aalto and K. Vehvilainen-Julkunen, 2008. Nurses' work environment and

nursing outcomes: A survey study among finnish university hospital registered nurses. International

Journal of Nursing Practice, 14(5): 357-365.

Thungjaroenkul, P., W. Kunaviktikul, P. Jacobs, G.G. Cummings and T. Akkadechanunt, 2008. Nurse staffing

and cost of care in adult intensive care units in a university hospital in Thailand. Nursing and Health

Sciences, 10: 31-36.

Tschannen, D. and B.J. Kalisch, 2009. The effect of variations in nurse staffing on patient length of stay in the

acute care setting. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 31: 153-170.

Twigg, D. and C. Duffield, 2009. A review of workload measures: A context for a new staffing methodology

in Western Australia. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(1): 132-140.

United

Nations,

2008.

The

millennium

development

goals

report.

Available

from

http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2008highlevel/pdf/newsroom/mdg%20reports/MDG_Report_2

008_ENGLISH.pdf.

Walker, L.O. and K.C. Avant, 2005. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. 4th Edn., Upper Saddle

River, N.J: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Wang, F.X., 2004. The needs of older adults: The trends of support older adults, problems and improving

strategies in community. Available from http://www.china.popin.com.

West, E., N. Mays, A.M. Rafferty, K. Rowan and C. Sanderson, 2009. Nursing resources and patient outcomes

in intensive care: A systematic review of the literature. International of Nursing Studies, 46(7): 9931011.

World Health Organization, 2003. The world health report 2003: Shaping the future. Available from

http://www.who.int/whr/2003/en/whr03_en.pdf.

World

Health

Organization,

2006.

The

world

health

report.

Available

from

http://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf.

World Health Organization, 2008. Country cooperation strategy at a glance. Available from

http://www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/EEDCEE6B-4224-4761-85320B867512274E/0/CCS20082013WHOChinaCHN.pdf.

Yang, K.P., 2003. Relationships between nurse staffing and patient outcomes. Journal of Nursing Research,

11(3): 149-158.

Yoder-Wise, P.S., 2003. Leading and managing in nursing. 3rd Edn., St. Louis: Mosby.

73