XPP-PDF Support Utility

advertisement

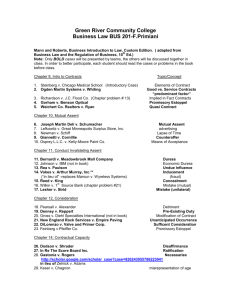

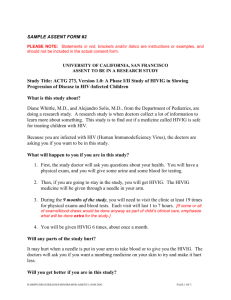

A BNA, INC. ELECTRONIC ! COMMERCE & LAW REPORT Reproduced with permission from Electronic Commerce & Law Report, Vol. 12, No. 32, 08/15/2007. Copyright 姝 2007 by The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. (800-372-1033) http://www.bna.com ELECTRONIC CONTRACTING The Ninth Circuit’s opinion in Douglas v. U.S. District Court for the Central District of California has been interpreted by some as a reversal of the trend toward permitting unilateral modification of online contracts, but given its specific facts and narrow holding, Douglas’s implications for current practices appear fairly limited. The author summarizes the legal background against which Douglas was decided, analyzes the Douglas holding, and offers several steps companies can take to mitigate the risk that courts will invalidate their online contracts due to lack of notice of proposed contract modifications. Notice, Assent Rules for Contract Changes After Douglas v. U.S. District Court BY LOTHAR DETERMANN Prof. Dr. Lothar Determann (www.lothar.determann.name) is a partner in the technology practice group of Baker & McKenzie LLP, San Francisco/Palo Alto office (www.bakernet.com) and teaches Computer and Internet law at the University of California Berkeley School of Law (Boalt Hall), University of San Francisco School of Law, and Freie Universität Berlin . The author is grateful for assistance by Agnieszka Purves, student at the University of California, Hastings College of Law, and Arezo Yazd, student at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law (Boalt Hall). COPYRIGHT 姝 2007 BY THE BUREAU OF NATIONAL AFFAIRS, INC. ore and more companies are moving away from ink and paper and towards click-through, shrink-wrap, browse-wrap and other automated contracting processes in the interest of administrative efficiency and mutual convenience. Some may see also an opportunity or risk that companies use automated processes with the primary objective to do away with contract negotiations and create an environment in which they can unilaterally dictate any unreasonable terms. But, market pressures and the doctrine of adhesion contracts limit the potential of such opportunities and risks, and in reality, it seems, many types of massmarket contracts are rarely negotiated anyhow, whether or not they are presented on paper or online (think of multiple page car rental agreements, real estate purchase contracts, bank account and loan documentation, insurance policies, etc.). M ISSN 1098-5190 2 As in the offline world, online contracting requires offer and acceptance, and acceptance can be declared expressly (e.g., by clicking on an ‘‘I accept’’ button), or implied by conduct upon receipt of notice. If companies want to rely on implied acceptance, they have to ensure that they provide adequate notice. What constitutes adequate notice depends on facts and circumstances in a particular situation. Following ProCD Inc. v. Zeidenberg, some U.S. courts have applied relatively lax standards as to the notice requirement.1 Douglas v. U.S. District Court for the Central District of California2 has been interpreted by some as an indication of a reversal in trends, but given its specific facts and narrow holding, its implications for current practices appear fairly limited. This article examines the decision, its context in prior case law and its potential ramifications for companies that need to update their online services terms or other mass-market agreements. Douglas v. U.S. District Court On June 7, 2007, the Ninth Circuit addressed in Douglas whether a company can change contracts with its existing customers by merely posting a link to new terms on its Web site, without any other notice regarding the change, even though the contracts to be changed were originally concluded offline and concerned services that were performed outside the Web site. A subscriber had entered into an offline contract for long distance telephone service. The phone company charged the subscriber’s credit card for monthly fees. The phone company was subsequently acquired, and the new management added charges and other terms in a revised version of the contract, which it posted on its home page. The district court considered such a posting to constitute sufficient notice, but the Ninth Circuit disagreed, because the subscriber had no duty to visit the phone company’s Web site, may not have visited it, and may thus never have received notice of the changes. Even if the subscriber had visited the Web site, he had no obligation to check the Web site for possible changes to the terms, which would have required a word-by-word, side-by-side analysis of the new versus the old terms, given that the phone company had not pointed out or explained the changes. This could not be expected from a subscriber, particularly not without separate notice, on a month-by-month basis. Thus, relying on general principles of contract law, the court determined that the subscriber was not bound by the new terms since he was never notified of the changes and without notice, there could not have been implied acceptance through conduct (continued use of services). The court also noted that even if the plaintiff had become bound by the new terms, these new terms could be unenforceable in California because they could be qualified as substantively unconscionable. First, the new contract included an arbitration clause, which the district court had found was not procedurally unconscionable under New York law (the law chosen in the phone company’s service terms) because the customer 1 86 F.3d 1447 (7th Cir. 1996). Exemplary cases are summarized in later in this article. 2 No. 06-75424, 2007 U.S. App. LEXIS 17061 (9th Cir. Jun. 7, 2007). 8-15-07 had meaningful alternatives as to telephone service. The Ninth Circuit applied California law and overturned the district court’s decision reasoning that under California law an adhesion contract can be procedurally unconscionable even if the customer has a meaningful choice of services. Further applying California law, the court also overturned the district court’s determination that the new contract terms waiving the right to participate in a class action were not substantively unconscionable. The court noted that contrary to New York law, under which class action waivers are not substantively unconscionable, such waivers may be unconscionable in California. Prior Law Contract formation traditionally requires offer and acceptance. Acceptance can be implied from the circumstances if the offeror receives notice of the offer terms and engages in conduct that manifests assent.3 Ordinarily, mutual assent involves one party making an offer, and the other side accepting that offer.4 However, it is not a strict requirement that ‘‘offer’’ and ‘‘acceptance’’ be precisely identifiable, as long as the overall circumstances show mutual assent.5 Acceptance of a given offer is the manifestation of assent to the terms of such offer in a manner prescribed or authorized by the offer. Generally, an acceptance must be communicated to the offeror in order to create a bilateral contract.6 However, there are situations in which a contract can be formed without a communicated acceptance. Specifically, acceptance may occur by silence or conduct where: (1) the offer expressly waives communication of acceptance, (2) the offer requires some act to signify acceptance, or (3) the offeree silently accepts benefits provided by the offeror. By the terms of her offer, the offeror may dispense with the general requirement that the offeree’s acceptance be communicated to her in order to perfect the agreement. Where the terms of an offer request an act other than words of acceptance and state that the performance of such act shall signify acceptance, a contract is formed when the offeree performs the requested act.7 The voluntary acceptance of the benefit of a transaction is equivalent to an assent to all the obligations arising from it, so far as the facts are known, or ought to be known, to the person accepting such benefit. 8 ProCD embodies these principles where it holds that shrink-wrap licenses are generally enforceable (unless a defense under general contract law applies to the terms themselves) since consumers have the option of returning the products if they do not wish to be bound by the terms. Choosing to keep the product is essen3 Restatement (Second) Contracts § 22(1). Id. 5 Restatement (Second) Contracts § 22(2); U.C.C. § 2204(1). 6 Restatement (Second) Contracts § 56. 7 Ticketmaster Corp. v. Tickets.com, 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 6483 (N.D. Cal. 2003). 8 Cal. Civil Code § 1589. 4 COPYRIGHT 姝 2007 BY THE BUREAU OF NATIONAL AFFAIRS, INC. ECLR ISSN 1098-5190 3 tially assenting to the terms of the shrink-wrap license. In contrast, earlier in Step-Saver Data Systems Inc. v. Wyse Technology,9 the court found that a software distributor was not bound by the terms of a shrink-wrap license because the delivery of the terms occurred after the contract formation stage had ended, with the effect that the U.C.C. Article 2 rules on additional terms therefore applied.10 Consistent with ProCD, however, the court stated that the terms would apply to the distributor’s customers. Many, but not all, decisions have followed the reasoning of ProCD and Step-Saver. In Lozano v. AT&T Wireless,11 the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California enforced an arbitration agreement contained in a ‘‘Welcome Guide’’ provided by a cellular phone company after the subscriber had signed his service plan. The location of the terms and conditions was disclosed on the second page of the guide, and they were the first thing mentioned in the entire booklet. The court, applying California law, opined that ‘‘providing customers with terms and conditions after an initial transaction is acceptable,’’ and that ‘‘such terms and conditions are enforceable.’’12 The Central District reasoned that ‘‘the economic and practical aspects of selling services to mass consumers allow for terms and conditions to follow an initial transaction.’’13 The court further emphasized the importance of the fact that the subscriber had been made aware of the existence and location of the terms and conditions. Similarly, in Bischoff v. DirecTV Inc.,14 the Central District faced the question whether DirecTV was entitled to arbitration under a service agreement that was provided to the subscriber (a business-to-consumer contract) with the first billing statement, after he had purchased the satellite equipment, ordered service over the phone, and started receiving DirecTV service. The Court reasoned that under general principles of contract law as they apply in California, the ‘‘economic and practical considerations involved in selling services to mass consumers [. . .] make it acceptable for terms and conditions to follow the initial transaction.’’ The court enforced the arbitration clause based on the fact that the customer kept accepting DirecTV service after receiving the terms and conditions when the contract was mailed to the customer.15 The principles in ProCD have also gained acceptance in the context of online contracting. For example, in Register.com Inc. v. Verio Inc.,16 the District Court for the Southern District of New York rejected Verio’s contention that it never manifested its assent to the terms of use on a domain name registrar’s home page that stated that submitting a query for access to registration information indicates the user’s agreement to the terms. Verio did not argue that it was unaware of the terms but rather raised the issue that it was never asked to click on an icon indicating its assent. The court concluded that Register.com’s terms were clearly posted on its 9 939 F.2d 91 (3d Cir. 1991). U.C.C. § 2-207. 11 216 F. Supp. 2d 1071 (C.D. Cal. 2002). 12 Id. at 1073. 13 Id. 14 180 F. Supp. 2d 1097 (C.D. Cal. 2002). 15 Id. at 1105. 16 126 F. Supp.2d 238 (S.D.N.Y. 2000). 10 ELECTRONIC COMMERCE & LAW REPORT ISSN 1098-5190 web site and Verio became bound by the terms when it proceeded in submitting a query. The U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts went even further and expressly applied ProCD to a click-wrap agreement.17 On facts similar to those in Step-Saver, the court concluded that if a shrink-wrap license agreement where assent is implicit is to be enforced, then there is even more of a reason to enforce a click-wrap license agreement where a consumer explicitly assents to the terms by clicking on an icon stating ‘‘I agree.’’ The court further went on to state that ProCD has replaced Step-Saver as the leading case on shrinkwrap agreements. On the contrary, in Specht v. Netscape Comms.,18 in response to a lawsuit for alleged violations of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, the defendants moved to compel arbitration under an arbitration clause in ‘‘browse-wrap’’ terms on the download page of Netscape’s Web site. The Second Circuit noted that the ‘‘browse-wrap’’ terms did not display an ‘‘I accept’’ button and were accessible only through a hyperlink that was placed below a ‘‘Download Now’’ button and would have only been visible if the users had scrolled down to the next screen and clicked on the link before hitting the ‘‘Download Now’’ button. Applying California law, the court considered such notice insufficient to support a finding of implied consent in the download act. Plaintiffs ‘‘were required neither to express unambiguous assent to that program’s license agreement nor even to view the license terms or become aware of their existence before proceeding with the invited download.’’19 In dictum, the Specht court suggests that the defendant could have easily created an enforceable contract by posting a notice and a link to the contract terms conspicuously above the download button and rename the button ‘‘I Accept’’ to clarify the legal significance of the download act. This approach certainly seems appropriate for this particular scenario, but it is worth noting that ‘‘I Accept’’ buttons are neither always required, nor always sufficient to facilitate contract formation (for example, if software license terms and an ‘‘I Accept’’ button are presented for the first time during a software installation process, long after products and purchase price are exchanged, it may not be appropriate to assume an ‘‘express acceptance’’ scenario, but rather query whether the circumstances really support a finding of assent implied through conduct–namely the pressing of a button with a primary goal to install software, not to agree to additional contract terms that the licensor should have presented when the license fees were paid).20 In Douglas, the Ninth Circuit Court distinguished the facts at issue with a fact pattern in predecessor cases in that the consumer was not a new user, but one who had been using his service for over four years, and who thus could not be expected to check or re-check contract 17 i.LAN Systems Inc. v. Netscout Service Level Corp., 183 F. Supp. 2d 328 (D. Mass 2002). 18 306 F.3d 17 (2d Cir. 2002). 19 Id. at 23. 20 It is questionable whether Specht provides a convincing analysis and adequate guidance for future decisions on issues of contract formation in the online and offline software licensing context. L. Determann and S.M. Ang-Olson, Comment on Specht v. Netscape, Intellectual Property Law Bulletin, University of San Francisco School of Law, Vol. 6, No. 2, p. 39 (2001); republished in 20 The Computer & Internet Lawyer 22 (2003). BNA 8-15-07 4 terms (while a new user can expect to be prompted to accept some form of services agreement and thus has a greater obligation to look out for it). Bischoff involved new customers who knew or should have known that they would be required to assent to contract terms when they sign on as a predicate for using the service.21 Thus, their use of the services without rejecting the company’s terms was enough to imply assent. In Douglas, however, the use of the services could not imply assent, because the customer was not on notice of the modified terms of the contract to begin with. Practical Take-Aways As discussed in this article, the immediate precedential rule of Douglas is actually quite narrow in scope: A company does not provide sufficient notice to support a finding of implied acceptance to facilitate contract formation if the company merely posts changed contract terms on a home page for consumers who are not contractually obligated or likely to visit such home page. Companies can avoid direct applicability of the Douglas rule by making even small changes to their contracting practices. For example: Establish Modification Right at Outset. In all contracts, companies could include a clause that expressly allows them to update the contract through online postings– regardless of whether the original contract is formed online or offline. Since courts seem to apply more relaxed standards to formation of new contracts, companies can seize the opportunity of the first contract to obtain the other party’s consent to future online contracting. This will address the Douglas court’s concern that the customers were not obligated or likely to actually review the Web postings. Highlight All Material Changes. If and when companies change their contracts, they could provide enhanced notices by placing conspicuous warnings (‘‘New Terms Apply’’) on their home page and in other routine communications (e.g., invoices or newsletters that are sent anyhow). But, given an increasing consumer aversion against e-mail and mail overload, companies have to think twice whether a contract update justifies a separate e-mail or letter to their customers. Companies could help consumers understand material changes by highlighting them in summaries or by providing redlined versions. This would address the Douglas court’s concern that the customers did not become aware of the changes. Collect and Retain Evidence of Assent. To retain the ability to prove notice, companies could try to retain Web logs on actual visits to their sites. However, this raises privacy concerns and could become overly expensive and burdensome. On the other hand, pop-up windows, flash screens, click-through steps or similar prompts for affirmative consent would address possible concerns both regarding the notice and assent elements of contract formation, but many users will find such requirements annoying and thus they are not practical in all circumstances. Affirmative ‘‘clicks’’ do not guarantee valid contract formation, because they can be coerced or solicited in circumstances that do not support a finding of implied 21 180 F. Supp. 2d at 1101. 8-15-07 assent (e.g., license terms popping up for the first time during product installation, after the licensee has already paid and received the products). But, companies that provide services through password protected web sites, where users have to log in, should—and usually do—cause new terms to pop up during the clickthrough/login process and require users to affirmatively click accept. Create Opportunity for Rejection. Short of requiring an affirmative act from the customer, companies can offer convenient opt-outs that may cause courts to find implied assent. For example, in the changed terms, companies could offer customers a convenient right of return/refund (in connection with product sales) or cost-free early termination (in connection with services contracts). Yet, at the outset remains the principle that silence does not mean assent, which works against the companies that are trying to update their terms. To overcome this obstacle to unilateral contract amendments, companies have to be careful and should provide enough time to their customers to consider the changes, for example, by announcing new terms 30+ days before they become effective. Some of these recommendations do not help companies that have to update legacy contracts. Particularly in a business-to-business context, such contracts may not mention Web postings at all, or to the contrary, expressly require that notices have to be served by mail and contract modifications have to be agreed upon in a writing hand signed by both parties, sometimes even providing for requirements as to the level of seniority of the signatories (‘‘duly appointed officer’’ or ‘‘Senior VP or above’’). At first glance, it seems, the company cannot update its terms unilaterally at all. But, it is worth noting that under California law, a customer may waive the signed writing requirement implicitly. A company may be able to create a situation in which such implied waiver can be proven if customers are notified of the proposed changes, customers do not object and they continue to use the product or service—such that the company has a detrimental reliance argument.22 Therefore, if a customer fails to respond to a conspicuous notice in an invoice, and keeps using the goods or services, this may be construed as a waiver of the requirement of a signed writing. Customers would forfeit their right to challenge the validity of the modified terms once the company starts providing further services in reliance on the new terms. Outlook If U.S. companies are starting to follow some or all of the recommendations suggested above, will their business partners—in particular consumers—be better served and protected? Should courts go further than Douglas and demand ‘‘I Accept’’ clicks on every Internet contract, like the court in Specht seems to prefer? Technologically, it can be done. Every Web site operator could theoretically require visitors to click ‘‘I Accept’’ on terms of use and privacy policies on an entry page, before visitors could see any 22 Cal. Civil Code § 1698(c); Heple v Kluge, 114 Cal.App.2d 473, 250 P.2d 694 (1952); Kayne v. First Charter Bank, 12 Cal.App.4th 1568, 1576 (1993). COPYRIGHT 姝 2007 BY THE BUREAU OF NATIONAL AFFAIRS, INC. ECLR ISSN 1098-5190 5 content. If some companies were starting to institute such a change, consumers would probably tend to avoid such Web sites, in order to escape the hassle of having click and log in all the time. But, if courts were demanding it and a majority of sites were implementing such changes, consumers would probably get used to the hassle. And click. And still not read the small print. It is safe to assume that in many cases involving challenges to unilateral changes to contract terms, the consumers disputing the validity of the changes would not have read the new terms even if they had received proper notice–just like consumers typically do not spend much time reading car rental agreements, real estate purchase contracts, loan documentation, insurance policies, etc., even if they have to sign such documents and perhaps even initial particular clauses. Yet, as the Douglas decision shows, it is sometimes easier to challenge contract formation on formal grounds (lack of notice, procedural unconscionability) than substantive grounds (unreasonable terms, substantive unconscionability). And, in any event, a good plaintiff’s attorney has to attack contract formation on both grounds, just to win the case. But, is notice really the only problem of one-sided agreements used in the mass-market context? If you believe in freedom of contract, market forces and competition, your answer should be ‘‘Yes.’’ But, not everyone does, and some jurisdictions are taking different approaches. Under German law, for example, it is quite easy to satisfy the notice requirement—companies merely have to show that their customers were or should have been aware that terms of use applied; but, German courts scrutinize non-negotiated contract terms very critically, compare each clause with the default rules in the German Civil Code, and invalidate any ELECTRONIC COMMERCE & LAW REPORT ISSN 1098-5190 clauses that derogate too significantly to the disadvantage of the customer—with the effect that disclaimers and limitations of liability are practically unenforceable. Italian law, on the contrary, allows disclaimers and other burdensome clauses, so long as they are initialed specifically by the customer (which could be implemented by separate check-boxes in the online context, although it is not clear yet whether Italian courts require handwritten acknowledgements). French law applies both substantive scrutiny and requires two separate acknowledgements—one that the customer has read the terms, and one that the customer agrees to them, i.e., two clicks. All other member states of the European Economic Area have implemented the Directive on Unfair Consumer Contract Terms (Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993 on Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts) in one way or another, and, as a result, companies cannot disclaim warranties, limit liabilities or prescribe dispute resolution terms as broadly as under U.S. law. But, this occurs in fundamentally different legal systems— which typically do not allow class action lawsuits and provide for much smaller damages awards as US courts. Given the traditionally very limited scope of the ‘‘contract of adhesion’’ doctrine in the United States, Douglas does not seem to indicate a radical trend in U.S. courts’ attitude towards freedom of contracting. It merely means that companies have to ensure that consumers receive notice of contract changes and indicate assent through some affirmative action following receipt of notice. Thus, Douglas seems less of a trendsetter and more a reminder and modest update on the law regarding contract updates. BNA 8-15-07