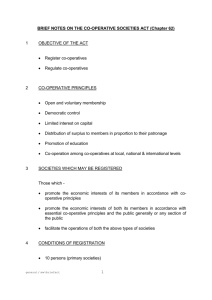

“The co-operative principle of limited return on capital needs to be

advertisement