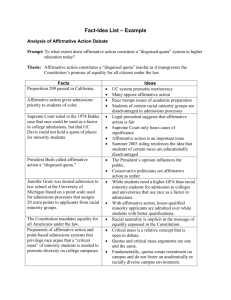

the supreme court 2012 term foreword: equality

advertisement